Chapter 3. Special Components: Dhandlers and Autohandlers

In previous chapters you’ve seen an overview of the basic structure and syntax of Mason components, and you’ve seen how components can cooperate by invoking one another and passing arguments.

In this chapter you’ll learn about dhandlers and autohandlers, two powerful mechanisms that help lend reusable structure to your site and help you design creative solutions to unique problems. Mason’s dhandlers provide a flexible way to create “virtual” URLs that don’t correspond directly to components on disk, and autohandlers let you easily control many structural aspects of your site with a powerful object-oriented metaphor.

Dhandlers

The term "dhandler”

stands for “default handler.” The

concept is simple: if Mason is asked to process a certain component

but that component does not exist in the component tree, Mason will

look for a component called dhandler

and serve that instead of the requested component. Mason looks for

dhandlers in the apparent requested directory and all parent

directories. For instance, if your web server receives a request for

/archives/2001/March/21 and passes that request

to Mason, but no such Mason component exists, Mason will sequentially

look for /archives/2001/March/dhandler,

/archives/2001/dhandler,

/archives/dhandler, and

/dhandler. If any of these components exist, the

search will terminate and Mason will serve the first dhandler it

finds, making the remainder of the requested component path available

to the dhandler via $m->dhandler_arg. For

instance, if the first dhandler found is

/archives/dhandler, then inside this component

(and any components it calls), $m->dhandler_arg

will return 2001/March/21. The dhandler can use

this information to decide how to process the request.

Dhandlers can be useful in many situations. Suppose you have a large number of documents that you want to serve to your users through your web site. These documents might be PDF files stored on a central document server, JPEG files stored in a database, text messages from an electronic mailing list archive (as in the example from the previous paragraph), or even PNG files that you create dynamically in response to user input. You may want to use Mason’s features to create or process these documents, but it wouldn’t be feasible to create a separate Mason component for each document on your server.

In many situations, the dhandler feature is simply a way to make URLs more attractive to the end user of the site. Most people probably prefer URLs like http://www.yoursite.com/docs/corporate/decisions.pdf over URLs like http://www.yoursite.com/doc.cgi?domain=corporate&format=pdf&content=decisions. It also lets you design an intuitive browsing interface, so that people who chop off the tail end of the URL and request http://www.yoursite.com/docs/corporate/ can see a listing of available corporate documents if your dhandler chooses to show one.

The alert reader may have noticed that using dhandlers is remarkably

similar to capturing the

PATH_INFO

environment variable in a CGI

application. In fact, this is not exactly true:

Apache’s

PATH_INFO

mechanism is actually available to you

if you’re running Mason under

mod_perl, but it gets triggered under different

conditions than does Mason’s dhandler mechanism.

If Apache receives a request with a certain path, say,

/path/to/missing/component, then its actions

depend on what the final existing part of that path is. If the

/path/to/missing/ directory exists but

doesn’t contain a component

file, then Mason will be invoked, a dhandler will be searched for,

and the remainder of the URL will be placed in

$m->dhandler_arg. On the other hand, if

/path/to/missing exists as a regular Mason

component instead of as a directory, this component will be invoked

by Mason and the remainder of the path will be placed (by Apache)

into $r->path_info. Note that the majority of

this handling is done by Apache; Mason steps into the picture after

Apache has already decided whether the given URL points to a file,

what that file is, and what the leftover bits are.

What are the implications of this? The behavioral differences

previously described may help you determine what strategy to use in

different situations. For example, if you’ve got a

bunch of content sitting in a database but you want to route requests

through a single Mason component, you may want to construct

“file-terminating” URLs and use

$r->path_info to get at the remaining bits.

However, if you’ve got a directory tree under

Mason’s control and you want to provide intelligent

behavior for requests that don’t exist (perhaps

involving customized 404 document generation, massaging of content

output, and so on) you may want to construct

“directory-terminating” URLs and

use $m->dhandler_arg to get at the rest.

Finer Control over Dhandlers

Occasionally you will want more control over how Mason delegates execution to dhandlers. Several customization mechanisms are available.

First, any component (including a dhandler) may decline to handle a

request, so that Mason continues its search for dhandlers up the

component tree. For instance, given components located at

/docs/component.mas,

/docs/dhandler, and

/dhandler,

/docs/component.mas may decline the request by

calling $m->decline, which passes control to

/docs/dhandler. If

/docs/dhandler calls

$m->decline, it will pass control to

/dhandler. Each component may do some processing

before declining, so that it may base its decision to decline on

specific user input, the state of the database, or the phase of the

moon. If any output has been generated,

$m->decline will clear the output buffer before

starting to process the next component.

Second, you may change the filename used for dhandlers, so that

instead of searching for files called dhandler,

Mason will search for files called default.mas

or any other name you might wish. To do this, set the

dhandler_name Interpreter parameter

(see Chapter 6 for details on setting parameters).

This may be useful if you use a text editor that recognizes Mason

component syntax (we mention some such editors in Appendix C) by file extension, if you want to configure

your web server to handle (or deny) requests based on file extension,

or if you simply don’t like the name

dhandler

.

D handlers and Apache Configuration

You may very well have something in your Apache configuration file that looks something like this:

DocumentRoot /home/httpd/html <FilesMatch "\.html$"> SetHandler perl-script PerlHandler HTML::Mason::ApacheHandler </FilesMatch>

This directive has a rather strange interaction with Mason’s dhandler mechanism. If you have a dhandler at /home/httpd/html/dhandler on the filesystem, which corresponds to the URL /dhandler and a request arrives for the URL /nonexistent.html, Mason will be asked to handle the request. Since the file doesn’t exist, Mason will call your dhandler, just as you would expect.

However, if you request the URL /subdir/nonexistent.html, Apache will never call Mason at all and will instead simply return a NOT FOUND (404) error. Why, you ask? A good question indeed. It turns out that in the process of answering the request, Apache notices that there is no /home/httpd/html/subdir directory on the filesystem before it even gets to the content generation phase, therefore it doesn’t invoke Mason. In fact, if you were to create an empty /home/httpd/html/subdir directory, Mason would be called.

One possible solution is simply to create empty directories for each path you would like to be handled by a dhandler, but this is not a very practical solution in most cases. Fortunately, you can add another configuration directive like this:

<Location /subdir> SetHandler perl-script PerlHandler HTML::Mason::ApacheHandler </Location>

This tells Apache that it should pass control to Mason for all URL

paths beginning with /subdir, regardless of what

directories exist on disk. Of course, using this

Location directive means that

all URLs under this location, including images,

will be served by Mason, so use it with care.

Autohandlers

Mason’s autohandler feature is one of its most powerful tools for managing complex web sites.

Managing duplication is a problem in any application, and web applications are no exception. For instance, if all pages on a given site should use the same (or similar) header and footer content, you immediately face a choice: should you simply duplicate all the common content in each individual page, or should you abstract it out into a central location that each page can reference? Anyone who’s worked on web sites knows that the first approach is foolhardy: as soon as you need to make even a minor change to the common content, you have to do some kind of find-and-replace across your entire site, a tedious and error-prone process.

For this reason, all decent web serving environments provide a way to include external chunks of data into the web pages they serve. A simple example of this is the Server Side Include mechanism in Apache and other web servers. A more sophisticated example is Mason’s own ability to call one component from inside another.

Although an include mechanism like this is absolutely necessary for a manageable web site, it doesn’t solve all the duplication problems you might encounter.

First, the onus of calling the correct shared elements still rests within each individual page. There is no simple way for a site manager to wave a wand over her web site and say, “Take all the pages in this directory and apply this header and this footer.” Instead, she must edit each individual page to add a reference to the proper header and footer, which sounds remarkably like the hassle we were trying to avoid in the first place. Anyone who has had to change the header and footer for one portion of a site without changing other portions of the site knows that include mechanisms aren’t the cat pajamas they’re cracked up to be.

Second, include mechanisms address only content duplication, not any other kind of shared functionality. They don’t let you share access control, content filtering, page initialization, or session management, to name just a few mechanisms that are typically shared across a site or a portion of a site.

To address these problems, Mason borrows a page from

object-oriented programming. One of

the central goals of object-oriented programming is to allow

efficient and flexible sharing of functionality, so that a

Rhododendron object can inherit from a

Plant object, avoiding the need to reimplement the

photosynthesize( ) method. Similarly, each

component in Mason may have a

parent

component, so that several components may have the same parent,

thereby sharing their common functionality.

To specify a component’s parent, use

the

inherit flag:

<%flags> inherit => 'mommy.mas' </%flags>

If a component doesn’t specify a parent explicitly, Mason may assign a default parent. This is (finally) how autohandlers come into the picture:

The default parent for any “regular” component (one that isn’t an autohandler — but might be a dhandler) is a component named “autohandler” in the same directory. If no autohandler exists in the same directory, Mason will look for an autohandler one directory up, then one more directory up, and so on, until reaching the top of the component root. If this search doesn’t find an autohandler, then no parent is assigned at all.

The default parent for an autohandler is an autohandler in a higher directory. In other words, an autohandler inherits just like any other component, except that it won’t inherit from itself.

Note that these are only the defaults; any component, including an

autohandler, may explicitly specify a parent by setting the

inherit flag. Be careful when assigning a parent

to an autohandler, though: you may end up with a circular inheritance

chain if the autohandler’s parent inherits (perhaps

by default) from the autohandler.

Just like dhandlers, you can change the component name used for the

autohandler mechanism from autohandler to

something else, by setting the Mason interpreter’s

autohandler_name

parameter.

We’ll use the standard object-oriented terminology when talking about the inheritance hierarchy: a component that has a parent is said to be a “child” that “inherits from” its parent (and its parent’s parent, and so on). At runtime, the hierarchy of parent and child components is often referred to in Mason as the “wrapping chain,” for reasons you are about to witness.

Example 3-1 and Example 3-2 show how to use autohandlers for our simple content-sharing scheme, adding common headers and footers to all the pages in a directory.

<html> <head><title>Example.com</title></head> <body> % $m->call_next; <br><a href="/">Home</a> </body> </html>

This demonstrates the first property of inheritance, which we call "content wrapping” — any component that inherits from the autohandler in Example 3-1, like /welcome.html in Example 3-2, will automatically be wrapped in the simple header and footer shown. Note that /welcome.html doesn’t need to explicitly insert a header and footer; that happens automatically via the autohandler mechanism.

Let’s trace through the details of the component processing. A request comes to the web server for http://example.com/welcome.html, which Mason translates into a request for the /welcome.html component. The component is found in the component path, so the dhandler mechanism is not invoked. /welcome.html doesn’t explicitly specify a parent, so Mason looks for a component named /autohandler, and it finds one. It then tries to determine a parent for /autohandler — because there are no directories above /autohandler and /autohandler doesn’t explicitly specify a parent, /autohandler remains parentless, and the construction of the inheritance hierarchy is complete.

Mason then begins processing /autohandler, the

top component in the parent hierarchy. The first part of the

component doesn’t contain any special Mason

sections, so it simply gets output as text. Mason then sees the call

to $m->call_next, which means that it should go

one step down the inheritance hierarchy and start processing its

child component, in this case /welcome.html. The

/welcome.html component generates some output,

which gets inserted into the middle of

/autohandler and then finishes. Control passes

back to /autohandler, which generates a little

more output and then finishes, ending the server response.

Using Autohandlers for Initialization

As we mentioned earlier, the autohandler mechanism can be applied to more than just header and footer generation. For the sake of dividing this material into reasonably sized chunks for learning, we’re leaving the more advanced object-oriented stuff like methods and attributes for Chapter 5. However, several extremely common autohandler techniques are presented here.

First, most interesting sites are going to interact with a database. Generally you’ll want to open the database connection at the beginning of the response and simply make the database handle available globally for the life of the request.[11] The autohandler provides a convenient way to do this (see Example 3-3 and Example 3-4).

<html>

<head><title>Example.com</title></head>

<body>

% $m->call_next;

<br><a href="/">Home</a>

</body>

</html>

<%init>

$dbh = DBI->connect('DBI:mysql:mydb;mysql_read_default_file=/home/ken/my.cnf')

or die "Can't connect to database: $DBI::errstr";

</%init><%args>

$user

</%args>

% if (defined $name) {

<p>Info for user '<% $user %>':</p>

<b>Name:</b> <% $name %><br>

<b>Age:</b> <% $age %><br>

% } else {

<p>Sorry, no such user '<% $user %>'.</p>

% }

<%init>

my ($name, $age) = $dbh->selectrow_array

("SELECT name, age FROM users WHERE user=?", undef, $user);

</%init>Note that the $dbh variable was not declared with

my( ) in either component, so it should be

declared using the Mason

allow_globals

parameter (or, equivalently, the

MasonAllowGlobals directive in an

Apache config file). The allow_globals parameter

tells the compiler to add use vars statements when

compiling components, allowing you to use the global variables you

specify. This is the easiest way to share variables among several

components in a request, but it should be used sparingly, since

having too many global variables can be difficult to manage.

We’ll give a brief trace-through of this example.

First, Mason receives a request for http://example.com/view_user.max?user=ken,

which it translates to a request for the

/view_user.mas component. As before, the

autohandler executes first, generating headers and footers, but now

also connecting to the database. When the autohandler passes control

to /view_user.mas, its

<%init> section runs and uses the

same

$dbh global

variable created in the autohandler. A couple of database values get

fetched and used in the output, and when control passes back to the

autohandler the request is finished.

Since this process is starting to get a little complicated under

scrutiny, you may wonder how the user parameter is

propagated through the inheritance hierarchy. The answer is that

it’s supplied to the autohandler, then passed

automatically to /view_user.mas through

$m->call_next. In fact,

$m->call_next is really just some sugar around

the $m->comp method, automatically selecting

the correct component (the child) and passing the

autohandler’s arguments through to the child. If you

like, you can supply additional arguments to the child by passing

them as arguments to

$m->call_next.

Using Autohandlers as Filters

Example 3-5 is another common use of

autohandlers.

Often the content of each page will need to be modified in some

systematic way, for example, transforming relative URLs in

<img src> tags into absolute URLs.

% $m->call_next;

<%init>

# Images are on images.mysite.com

(my $host = $r->hostname) =~ s/^.*?(\w+\.\w+)$/images.$1/;

# Remove final filename from path to get directory

(my $path = $r->uri) =~ s,/[^/]+$,,;

<%init>

<%filter>

# Matches site-relative paths

s{(<img[^>]+src=\")/} {$1http://$host/}ig;

# Matches directory-relative paths

s{(<img[^>]+src=\")(?!\w+:)} {$1http://$host$path/}ig;

</%filter>This particular autohandler doesn’t add a header and

footer to the page, but there’s no reason it

couldn’t. Any additional content in the autohandler

would function just as in our previous example and also get filtered

just like the content from call_next( ).

We make two substitution passes through the page. The first pass

transforms URLs like <img src="/img/picture.gif"> into <img src="http://images.mysite.com/img/picture.gif">. The

second pass transforms URLs like <img src="picture.gif"> into <img src="http://images.mysite.com/current_dir/picture.gif">.

Filter sections like this can be very handy for changing image paths, altering navigation bars to match the state of the current page, or making other simple transformations. It’s not a great idea to use filters for very sophisticated processing, though, because parsing HTML can give you a stomach ache very quickly. In Chapter 5 you’ll see how to use inheritance to gain finer control over the production of the HTML in the first place, so that often no filtering is necessary.

Inspecting the Wrapping Chain

When Mason processes a request, it builds the wrapping chain and then executes each component in the chain, starting with the topmost parent component and working its way toward the bottommost child. Inside one of these components you may find it necessary to access individual components from the chain, and several Mason methods exist for this purpose.

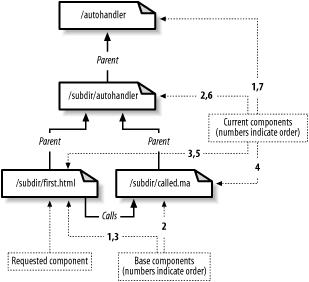

For orientation purposes, let’s define a little more terminology. The term " requested component” refers to the component originally requested by a URL or to a dhandler if that component doesn’t exist. The term " current component” refers to the component currently executing at any given time. The term “base component” refers to the bottommost child of the current component. The base component starts out as the requested component, but as components call one another during a request, the base component will take on several different values. Note that the requested component is determined only once per request, but the current component and the base component will typically change several times as the request is handled

An example scenario is illustrated in Figure 3-1.

If /subdir/first.html is called as the requested

component, its parent will be

/subdir/autohandler and its grandparent will be

/autohandler. These three components make up the

initial inheritance chain, and while

/subdir/first.html is executing, it will be

designated as the base component. Its content gets wrapped by its

parents’ content, so the component execution starts

with /autohandler, which calls

/subdir/autohandler via

$m->call_next, which in turn calls

/subdir/first.html by the same mechanism. While

any of these components is executing, it temporarily becomes the

current component, though the base component stays fixed as

/subdir/first.html.

If /subdir/first.html calls <& called.mas &> during the request,

/subdir/called.mas temporarily becomes both the

current component and the base component. Note that its parents do

not go through the content wrapping phase again;

this happens only for the requested component. When

/subdir/called.mas finishes, control passes back

to /subdir/first.html, which becomes the base

component and current component again. It remains the base component

for the duration of the request as its parents become the current

components so they can finish their content wrapping.

To access the base component, current component, or requested

component in your code, you can use the

$m->base_comp,

$m->current_comp, or

$m->request_comp request methods. Each of these

methods returns an object representing the component itself. These

objects inherit from the HTML::Mason::Component

class, and they can be used in several ways.

First, a component object can be used as the first argument of

$m->comp( ) or <& &> in place of the component name. Second, you can

access a component’s parent by calling its

parent( ) method, which returns another component

object. Third, you can access methods or attributes that a component

or its parents define in <%method> or

<%attr> blocks. Finally, the

HTML::Mason::Component class and its subclasses

define several methods that let you query properties of the component

itself, such as its creation time, what arguments it declares in its

<%args> section, where its compiled form is

cached on disk, and so on. See Chapter 4 for more

information on the HTML::Mason::Component family

of classes.

Using Autohandlers and Dhandlers Together

Despite their similar names, the autohandler and dhandler mechanisms are actually totally distinct and can be used independently or in tandem. In this section we look at some ways to use autohandlers and dhandlers together.

Most important about the way dhandlers and autohandlers interact is that Mason first figures out how to resolve a path to a component name, then figures out the inheritance of that component. In other words, Mason determines dhandlers before it determines autohandlers. This has several consequences.

First, it means that a dhandler may use the inheritance mechanism

just like any other component can. A component called

/trains/dhandler may specify its parent using

the inherit flag, or it may inherit from

/trains/autohandler or

/autohandler by default.

Second, if Mason receives a request for /one/two/three.mas, and the component root contains components called /one/two/autohandler and /one/dhandler but no /one/two/three.mas, Mason will first determine that the proper requested component for this request is /one/dhandler, then it will search the component root for any appropriate parents. Since the autohandler is located in the /one/two/ directory, it won’t be invoked when serving /one/.

An example from John Williams (a frequent and important contributor to the Mason core) helps illustrate one powerful way of using dhandlers and autohandlers together. Suppose you’re running a web site that serves news articles, with articles identified by the date they were written. Normally articles get published once a day, but once in a while there’s a day without an article published.

Say you get a request for /archive/2001/march/21. A dhandler at /archive/dhandler could provide the content for any missing files, for example by finding the latest article whose date is before the requested date. An autohandler at /archive/autohandler or /autohandler could provide the sitewide header and footer in a uniform fashion, not caring whether the article had its own component file or whether it was generated by the dhandler.

Remember, autohandlers and dhandlers are distinct features in Mason, and by combining them creatively you can achieve very powerful results.

[11] This strategy can be used in conjunction

with the Apache::DBI module, which allows for

database connections that persist over many requests.

Get Embedding Perl in HTML with Mason now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.