A large part of system administration involves dealing with files and directories: creating directories, copying files, moving files and directories around, and deleting them. Fedora provides a powerful set of tools for managing files from the shell prompt as well as graphically.

Linux, like most modern operating systems, uses a tree-like hierarchy to store and organize files. To manage files effectively, extend the hierarchy to organize your data.

Fedora’s master directory (or folder, as it would be referred to by other operating systems) is called the root directory; it may contain files and directories. Each of those directories may in turn contain other files and directories.

For each user, one directory is designated as the home directory, and that is where that user stores her personal files. Additionally, each process (a running copy of a program) has a current working directory on the system, which is the directory that it accesses by default unless another directory is explicitly specified.

The root directory is always the same system-wide; the home directory is consistent for a particular user, but varies from user to user; and the current working directory is unique to each process and can be changed anytime.

A

pathname specifies how to find a file in the file hierarchy. There are three different pathname schemes that can be used, based on the three different starting points (root, home, and current working directory); each scheme specifies the path from the selected starting point to the desired file, separating directory names with the forward

slash character (/). These three schemes are summarized in Table 4-4.

Table 4-4. Absolute, Relative, and Relative-to-Home pathnames

The special symbols

. (same directory) and .. (parent directory) are useful in pathnames. For example, if your current directory is /home/chris/book, then ../invitation refers to /home/chris/invitation.

Fedora uses a standard set of directories derived from historical conventions, the Linux Standard Base (LSB) project, and the kernel. Table 4-5 outlines the key directories and their purpose.

Table 4-5. Key directories in Fedora Core

Local files refers to files—binaries, scripts, and datafiles—that you have developed and that are not part of Fedora. Separating these files from the rest of the operating system makes it easier to move them to a new system in the future.

The

wildcard characters ? and * can be used for pattern matching, which is useful for dealing with several files at a time without individually specifying each filename. ? will match any one character in a filename, and * will match any number of any characters (including none).

Square brackets [] can be used to contain a list of characters [123], a range of characters [a–j], or a combined list and range [123a–j]; this pattern will match any one character from the list or range. Using an

exclamation mark or carat symbol as the first character inside the square brackets will invert the meaning, causing a match with any one character which is not in the list or range.

Table 4-6 lists some examples of ambiguous filenames.

Table 4-6. Ambiguous filenames

Linux filenames can be up to 254 characters long and contain letters, spaces, digits, and most punctuation marks. However, names that contain certain punctuation marks or spaces cannot be used as command arguments unless you place quote marks around the name (and even then there may be problems). Linux filenames are also case-sensitive, so it’s productive to adopt a consistent naming convention and stick to it.

Here are my recommendations for Linux filenames:

Build the names from lowercase letters, digits, dots, hyphens, and underscores. Avoid all other punctuation. Start the filename with a letter or digit (unless you want to specify a hidden file), and do not include spaces.

Tip

Although it makes command-line file manipulation more awkward, more and more users are adding spaces to photo and music filenames.

Use the single form of words instead of the plural (font instead of fonts); it’s less typing, and you won’t have to keep track of whether you chose the singular or plural form.

Filename extensions (such as .gif, .txt, or .odt) are not recognized by the Linux kernel; instead, the file contents and security permissions determine how a file is treated. However, some applications do use extensions as an indication of file type, so it’s a good idea to employ traditional extensions such as .mp3 for MP3 audio files and .png for portable network graphics files.

The ls (list-directory-contents) command will display a list of the files in the current working directory:

$ ls

4Suite crontab hosts libuser.conf nxserver

a2ps.cfg cron.weekly hosts.allow lisarc oaf

...(Lines snipped)...You can specify an alternate directory or file pattern as an argument:

$lsbin etc lost+found mnt proc sbin sys usr boot home media net ptal selinux tftpboot var dev lib misc opt root srv tmp $/ls -da2ps.cfg alsa ant.conf audit.rules a2ps-site.cfg alternatives ant.d auto.master acpi amanda asound.state auto.misc adjtime amandates atalk auto.net alchemist amd.conf at.deny auto.smb aliases amd.net atmsigd.conf aliases.db anacrontab auditd.confa*

By default, filenames starting with a

dot (.) are not shown. This provides a convenient way to store information such as a program configuration in a file without constantly seeing the filename in directory listings; you’ll encounter many dot files and directories in your home directory. If you wish to see these “hidden” files, add the -a (all) option:

$ ls -a

ls can display more than just the name of each file. The -l (long) option will change the output to include the security permissions, number of names, user and group name, file size in bytes, and the date and time of last modification:

$ ls -l

-rw------- 1 chris chris 3962 Aug 29 02:57 a2script

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 17001 Aug 29 02:57 ab1

-rw------- 1 chris chris 2094 Aug 29 02:57 ab1.c

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 884 Aug 29 02:57 perl1

-rw------- 1 chris chris 884 Aug 29 02:57 perl1.bck

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 55 Aug 29 02:57 perl2

-rw------- 1 chris chris 55 Aug 29 02:57 perl2.bck

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 11704 Aug 29 02:57 pointer1

-rw------- 1 chris chris 228 Aug 29 02:57 pointer1.c

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 12974 Aug 29 02:57 pp1

-rw------- 1 chris chris 2294 Aug 29 02:57 pp1.cTip

ls

-l is so frequently used that Fedora has a predefined alias (shorthand) for it: ll.

You can also sort by file size (from largest to smallest) using -S:

$ ls -S -l

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 17001 Aug 29 02:57 ab1

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 12974 Aug 29 02:57 pp1

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 11704 Aug 29 02:57 pointer1

-rw------- 1 chris chris 3962 Aug 29 02:57 a2script

-rw------- 1 chris chris 2294 Aug 29 02:57 pp1.c

-rw------- 1 chris chris 2094 Aug 29 02:57 ab1.c

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 884 Aug 29 02:57 perl1

-rw------- 1 chris chris 884 Aug 29 02:57 perl1.bck

-rw------- 1 chris chris 228 Aug 29 02:57 pointer1.c

-rwx------ 1 chris chris 55 Aug 29 02:57 perl2

-rw------- 1 chris chris 55 Aug 29 02:57 perl2.bck

The first character on each line is the file type: - for plain files, d for directories, and l for symbolic links.

There are dozens of options to the ls command; see its manpage for details.

To print the name of the current working directory, use the pwd (print-working-directory) command:

$ pwd

/home/chrisTo change the directory, use the

cd (change-directory) command.

To change to the /tmp directory:

$cd/tmp

To change to the foo directory within the current directory:

$cdfoo

To change back to the directory you were in before the last cd command:

$cd-

To change to your home directory:

$ cdTo change to the book directory within your home directory, regardless of the current working directory:

$cd~/book

To change to jason’s home directory:

$cd ~jason/

To create a directory from the command line, use the mkdir command:

$mkdirnewdirectory

This will create newdirectory in the current working directory. You could also specify the directory name using an absolute or relative-to-home pathname.

To create a chain of directories, or a directory when one or more of the parent directories might not exist, use the -p (path) option:

$mkdir -pfoo/bar/baz/qux

This has the side effect of turning off any warning messages if the directory already exists.

To delete a directory that is empty, use rmdir:

$rmdirnewdirectory

This will fail if the directory is not empty. To delete a directory as well as all of the directories and files within that directory, use the

rm (remove) command with the -r (recursive) option:

$rm -rnewdirectory

Warning

rm

-r can delete hundreds or thousands of files without further confirmation. Use it carefully!

To copy a file, use the cp command with the source and destination filenames as positional arguments:

$cp/etc/passwd/tmp/passwd-copy

This will make a copy of /etc/passwd named /tmp/passwd-copy. You can copy multiple files with a single cp command as long as the destination is a directory; for example, to copy /etc/passwd to /tmp/passwd and /etc/hosts to /tmp/hosts:

$cp/etc/passwd/etc/hosts/tmp

In Linux, renaming and moving files are considered the same operation and are performed with the mv command. In either cases, you’re changing the pathname under which the file is stored without changing the contents of the file.

To change a file named yellow to be named purple in the current directory:

$mvyellow purple

To move the file orange from jason’s home directory to your own:

$mv~jason/orange ~

The rm command will remove (delete) a file:

$rmbadfile

You will not be prompted for confirmation as long as you are the owner of the file. To disable confirmation in all cases, use -f (force):

$rm -fbadfile

Or to enable confirmation in all cases, use -i (interactive):

$rm -irm: remove regular empty filebadfile\Qbadfile'?y

Linux systems store files by number (the

inode number). You can view the inode number of a file by using the -i option to

ls:

$ls -i3410634 /etc/hosts/etc/hosts

A filename is cross-referenced to the corresponding inode number by a link—and there’s no reason why several links can’t point to the same inode number, resulting in a file with multiple names.

This is useful in several situations. For example, the links can appear in different directories, giving convenient access to one file from two parts of the filesystem, or a file can be given a long and detailed name as well as a short name to reduce typing.

Links are created using the

ln command. The first argument is an existing filename (source), and the last argument is the filename to be created (destination), just like the cp and mv commands. If multiple source filenames are given, the destination must be a directory.

For example, to create a link to /etc/passwd named ~/passwords, type:

$ln/etc/passwd ~/passwords

The second column in the output from ls -l displays the number of links on a file:

$ls -l-rw-rw-r-- 1 chris chris 23871 Oct 13 01:00 electric.mp3 $electric.mp3rm$zap.mp3ln$electric.mp3 zap.mp3ls -l-rw-rw-r-- 2 chris chris 23871 Oct 13 01:00 electric.mp3electric.mp3

Although these types of links, called hard links, are very useful, they suffer from three main limitations:

The alternative to a hard link is a symbolic link, which links one filename to another filename instead of linking a filename to an inode number. This provides a work-around for all three of the limitations of hard links.

The

ln command creates symbolic links when the -s argument is specified:

$ls -l-rw-rw-r-- 1 chris chris 1539071 Oct 13 01:06 ants.avi $ants.aviln -s$ants.avi ants_in_ant_farm.avils -l-rw-rw-r-- 1 chris chris 1539071 Oct 13 01:06 ants.avi lrwxrwxrwx 1 chris chris 8 Oct 13 01:06 ants_in_ant_farm.avi -> ants.avi*ants*

Notice that the the link count on the the target does not increase when a symbolic link is created, and that the ls -l output clearly shows the target of the link.

The file command will read the first part of a file, analyze it, and display information about the type of data in the file. Supply one or more filenames as the argument:

$ file *

fable: ASCII text

newicon.png: empty

passwd: ASCII text

README: ASCII English text

xpdf.png: PNG image data, 48 x 48, 8-bit/color RGBA, non-interlaced

You can display the contents of a text file using the

cat command:

$catDia is a program for drawing structured diagrams. ...(more)...README

Tip

If you accidentally cat a non-text file, your terminal display can get really messed up. The reset command will clear up the situation:

,l*l<lL\xe2 ,,<lFL<<<G\\l<lGRL<l\xe2 \xf5 <L,l<lLl\LLLl<*]US]$$][]UWVS[ j)Eue[^_1PuuuG;re[^_UUSR@t@CuX[USP[n X[xG hG6QGListxG!GN9Akregator11ApplicationE <L\L 2hLl\xe2 \xf5 [&&*CS@&*_^-&@$#D]$ reset[chris@concord2 ~]$To display only the top or bottom 10 lines of a text file, use the head or tail command instead of cat.

If the text file is too big to fit on the screen, the less command is used to scroll through it.

$lessREADME

You can use the up and down arrow keys and the Page Up/Page Down keys to scroll, and the q key to quit. Press the h key for help on other options, such as searching.

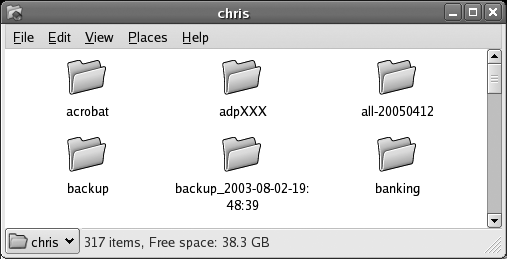

GNOME’s file manager is named Nautilus and it permits simple drag-and-drop file management.

When you are logged in to GNOME, Nautilus is already running as part of the desktop environment. To open a Nautilus window, double-click on the Home icon on your desktop or select a folder from the Places menu. A window will appear, such as the one shown in Figure 4-2, showing each file as an icon. Emblems overlaid on the icons are used to indicate the file status, such as read-only.

By default, Nautilus uses a spatial mode, which means that each directory will open in a separate window, and those windows will retain their position when closed, re-opening at the same location when you access them later.

You can open child directories by double-clicking on them, or you can open a parent directory using the pull-down menu in the bottom-lefthand corner of the window. To deal with more than one directory (for example, for a copy or move operation), open windows for each of the directories and arrange them on the screen so that they are not overlapping.

To manage files, start by selecting one or more files:

To select a single file, click on it.

To select several files that are located close together, click on a point to the left or right of the files (which will start drawing a rectangle) and then drag the mouse pointer so that the rectangle touches all of the files you wish to select.

To select several files that are not adjacent, click on the first one, and then hold Ctrl and click on additional ones.

To select a consecutive range of files, click on the first file, and then hold Shift and click on the last file.

Once you have selected a file (or files):

Move the file by dragging it between windows.

Copy a file by dragging it between windows while holding the Ctrl key.

Link a file (symbolically) by dragging it between windows while holding the Ctrl and Shift keys.

Delete a file by dragging it and dropping it on the Trash icon on the desktop, by pressing the Delete key, or by right-clicking and selecting “Move to Trash.”

To rename a file, right-click, select Rename, and then edit the name below the file icon.

You can also use traditional cut, copy, and paste operations on the files:

To cut a file, press Ctrl-X, or right-click and select Cut. Note that the file will not disappear from the original location until it is pasted into a new location; this effectively performs a move operation.

To copy a file, press Ctrl-C, or right-click and select Copy.

To paste a file that has been cut or copied, click on the window of the directory you with to paste into, and then press Ctrl-V or right-click on the window background and select Paste.

You can also perform cut, copy, and paste operations from the Edit menu at the top of the Nautilus window.

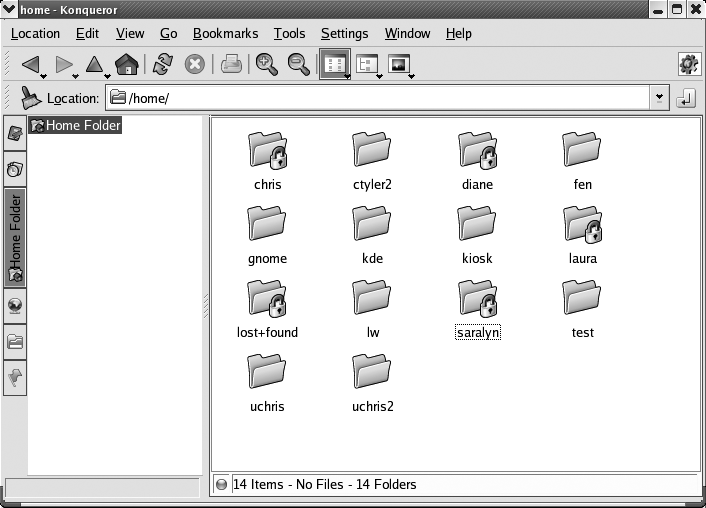

KDE’s Konqueror is both a file manager and a web browser. Figure 4-3 shows the file manager view. Although at first glance this looks similar to Nautilus, Konqueror offers a larger set of features, most of which are accessed through the toolbar and menus.

To start Konqueror, select Home from the K menu. Unlike Nautilus, Konqueror does not use spatial windows; as you move around the file hierarchy, the same window is reused. To create a second window for drag-and-drop, press Ctrl-N (or select the menu option Location→New Window). Alternately, you can split a window horizontally or vertically using the Window menu, and then drag and drop between the two panes. To view more information about the files, select the menu option View→View Mode→Detailed List View, which shows information similar to that displayed by ls

-l. There are other options on the View Mode menu that are useful in different situations, such as the Photobook view for directories of photographs.

You can change to child directories by double-clicking on them, or you can change to parent directories by using the up-arrow icon on the toolbar. You can also select a directory from the Navigation Panel, shown on the left in Figure 4-3 (the Navigation Panel can be toggled on and off using the F9 key).

To manage files, start by selecting one or more files:

To select a single file, click on it.

To select several files that are located close together, click on a point to the left or right of the files (which will start drawing a rectangle) and then drag the mouse pointer so that the rectangle touches all of the files you wish to select.

To select several files that are not adjacent, click on the first one, and then hold Ctrl and click on additional ones.

To select a range of files (rectangular region), click on the first file, and then hold Shift and click on the last file.

Once you have selected a file (or files):

Move, copy, or link the file by dragging it between windows (or window panes). When you drop the file on the destination, a pop-up menu will appear with Move Here, Copy Here, and Link Here options.

Delete a file by dragging and dropping it on the Trash icon on the desktop, by pressing the Delete key, or by right-clicking and selecting “Move to Trash.”

To rename a file, right-click, select Rename, and then edit the name below the file icon.

As with Nautilus, you can also use traditional cut, copy, and paste operations on the files:

To cut a file, press Ctrl-X, or right-click and select Cut. Note that the file will not disappear from the original location until it is pasted into a new location; this effectively performs a move operation.

To copy a file, press Ctrl-C or right-click and select Copy.

To paste a file that has been cut or copied, click on the window of the directory you wish to paste into, and then press Ctrl-V, or right-click on the window background and select Paste.

You can also perform cut, copy, and paste operations using the Edit menu at the top of the Konqueror window.

Linux shells use a process called globbing to find matches for ambiguous filenames before commands are executed. Consider this command:

$ls/etc/*release*

When the user presses Enter, the shell converts /etc/*release* into a list of matching filenames before it executes the command. The command effectively becomes:

$ ls /etc/fedora-release /etc/lsb-release /etc/redhat-releaseThis is different from some other platforms, where the application itself is responsible for filename expansion. The use of shell globbing simplifies the design of software, but it can cause unexpected side effects when an argument is not intended to be a filename. For example, the echo command is used to display messages:

$ echo This is a test.

This is a test.However, if you add stars to either side of the message, then globbing will kick in and expand those stars to a list of all files in the current directory:

$ echo *** This is a test. ***

bin boot dev etc home lib lost+found media misc mnt net opt proc ptal root sbin selinux srv sys tftpboot tmp usr var This is a test. bin boot dev etc home lib lost+found media misc mnt net opt proc ptal root sbin selinux srv sys tftpboot tmp usr varThe solution is to quote the argument to prevent globbing:

$ echo "*** This is a test. ***"

*** This is a test. ***Microsoft Windows uses drive designators at the start of pathnames, such as the C: in C:\Windows\System32\foo.dll, to indicate which disk drive a particular file is on. Linux instead merges all active filesystems into a single file hierarchy; different drives and partitions are grafted onto the tree in a process called mounting.

You can view the mount table, showing which devices are mounted at which points in the tree, by using the mount command:

$ mount

/dev/mapper/main-root on / type ext3 (rw)

/dev/proc on /proc type proc (rw)

/dev/sys on /sys type sysfs (rw)

/dev/devpts on /dev/pts type devpts (rw,gid=5,mode=620)

/dev/md0 on /boot type ext3 (rw)

/dev/shm on /dev/shm type tmpfs (rw)

/dev/mapper/main-home on /home type ext3 (rw)

/dev/mapper/main-var on /var type ext3 (rw)

/dev/sdc1 on /media/usbdisk type vfat

(rw,nosuid,nodev,_netdev,fscontext=system_u:object_r:removable_t,user=chris)Or you can view the same information in a slightly more readable form, along with free-space statistics, by running the

df command; here I’ve used the -h option so that free space is displayed in human-friendly units (gigabytes, megabytes) rather than disk blocks:

$ df -h

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/mapper/main-root

30G 12G 17G 42% /

/dev/md0 251M 29M 210M 13% /boot

/dev/shm 506M 0 506M 0% /dev/shm

/dev/mapper/main-home

48G 6.6G 39G 15% /home

/dev/mapper/main-var 30G 13G 16G 45% /var

/dev/sdc1 63M 21M 42M 34% /media/usbdiskNote that /media/usbdisk is a flash drive, and that /home and /var are stored on separate disk partitions from /.

While the cursor is on or adjacent to the ambiguous filename, press Tab twice. bash will display all of the matching filenames, and then reprint the command and let you continue editing:

$lsa*a2.html all-20090412 a3f1.html $(press Tab, Tab)ls a*

Alternately, press Esc-* and bash will replace the ambiguous filename with a list of matching filenames:

$ls a*$(press Esc-*)ls a2.html all-20050412 a3f1.html

Type the first few characters of the filename, then press Tab. bash will fill in the rest of the name (or as much as is unique). For example, if there is only one filename in the current directory that starts with all:

$ls all$(press Tab)ls all-20090412

The Linux Standard Base project: http://www.linuxbase.org/

The manpages for bash, rm, cp, mv, ls, file, and less

Get Fedora Linux now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.