It takes discipline to use HTML/XHTML content-based style tags, since it is easier to simply think of how your text should look, not necessarily what it may also mean. Once you get started using content-based styles, your documents will be more consistent and better lend themselves to automated searching and content compilation.

First introduced in HTML 4.0, the

<abbr>

tag indicates that the

enclosed text is an abbreviated form of a longer word or phrase. The

browser might use this information to change the way it renders the

enclosed text or substitute alternative text. Might — none of the

popular browsers currently does anything to the text enclosed by the

<abbr> tag, and we can’t

predict how future versions will implement the tag.

The <acronym>

tag

indicates that the enclosed text is an acronym, an abbreviation

formed from the first letter of each word in a name or phrase, such

as HTML or IBM. Like <abbr>, the popular

browsers don’t appear to change the display of the

<acronym> content-based style tag.

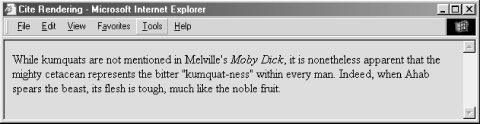

The

<cite>

tag usually indicates

that the enclosed text is a bibliographic citation, such as a book or

magazine title. By convention, the citation text is rendered in

italic. See Figure 4-7 for how Internet Explorer

renders this source text:

While kumquats are not mentioned in Melville's <cite>Moby Dick</cite>, it is nonetheless apparent that the mighty cetacean represents the bitter "kumquat-ness" within every man. Indeed, when Ahab spears the beast, its flesh is tough, much like the noble fruit.

Use the <cite> tag to set apart any

reference to another document, especially those in traditional media,

such as books, magazines, journal articles, and the like. If an

online version of the referenced work exists, you also should enclose

the citation within the <a> tag in order to

make it a hyperlink to that online version.

The <cite> tag also has a hidden feature: it

enables you or someone else to automatically extract a bibliography

from your documents. It is easy to envision a browser that compiles

tables of citations automatically, displaying them as footnotes or as

a separate document entirely. The semantics of the

<cite> tag go far beyond changing the

appearance of the enclosed text; they enable the browser to present

the content to the user in a variety of useful ways.

Software code warriors

have become accustomed to a special style of text presentation for

their source programs. The <code> tag is for

them. It renders the enclosed text in a monospaced, teletype-style

font like Courier, familiar to most programmers and readers of

O’Reilly books such as this one.

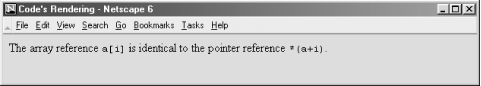

This following bit of en<code>ed text is

rendered in a monospaced font style by Netscape, as shown in Figure 4-8:

The array reference <code>a[i]</code> is identical to the pointer reference <code>*(a+i)</code>.

You should use the <code> tag for text that

represents computer source code or other machine-readable content.

While the <code> tag usually just makes text

appear in a monospaced font, the implication is that it is source

code, and future browsers may add other display effects.[22] For example, a

programmer’s browser might look for

<code> segments and perform some additional

text formatting, like special indentation of loops and conditional

clauses. If the only effect you desire is a monospaced font, use the

<tt> tag. Or if you want to display the

programming code in rigidly formatted monospaced text, use the

<pre> tag. [<pre>]

Use <dfn>

to tag

defining instances of special terms or phrases. The popular browsers

typically display <dfn> text in italics. In

the future, <dfn> might assist in creating a

document index or glossary.

For example, use the <dfn> tag to introduce

a new phrase to the reader:

When analyzing annual crop yields, <dfn>rind spectroscopy</dfn> may prove useful. By comparing the relative levels of saturated hydrocarbons in fruit from adjacent trees, rind spectroscopy has been shown to be 87% effective in predicting an outbreak of trunk dropsy in trees under four years old.

Notice that we delimit only the first occurrence of

“rind spectroscopy” with a

<dfn> tag in the example. Good style tells

us not to clutter the text with highlighted text. As with the many

other content-related and physical style tags, the fewer the

better.[23] As a general style, especially in technical

documentation, set off new terms when they are first introduced to

help your readers better understand the topic at hand, but resist

tagging the terms thereafter.

The <em>

tag tells the

client browser to present the enclosed text with emphasis. For nearly

all browsers, this means the text is rendered in italic. For example,

the popular browsers will emphasize by italicizing the words

“always” and

“never” in the following HTML/XHTML

source:

Kumquat growers must <em>always</em> refer to kumquats as "the noble fruit," <em>never</em> as just a "fruit."

Adding emphasis to your text is tricky business. Too little, and the emphatic phrases may be lost. Too much, and you lose the urgency. Like any seasoning, emphasis is best used sparingly.

Although invariably displayed in italic, the

<em> tag has broader implications as well,

and someday browsers may render emphasized text with a different

special effect. The <i> tag explicitly

italicizes text; use it if all you want is italic. Alternatively, you

can include text display-altering cascading style definitions in your

document.

Besides for emphasis, also consider using

<em> when presenting new terms or as a fixed

style when referring to a specific type of term or concept. For

instance, one of O’Reilly’s book

styles is to specially format file and device names. The

<em> tag might be used to differentiate

those terms from simple italics used for emphasis.

Speaking of special

styles for technical concepts, there is the

<kbd> tag. As you probably already suspect,

it is used to indicate text that is typed on a keyboard. Its enclosed

text typically is rendered by the browser in a monospaced font.

The <kbd> tag is most often used in

computer-related documentation and manuals, such as in this example:

Type <kbd>quit</kbd> to exit the utility, or type <kbd>menu</kbd> to return to the main menu.

The <samp>

tag indicates a

sequence of literal characters that should have no other

interpretation by the user. This tag is most often used when a

sequence of characters is taken out of its normal context. For

example, the following source:

The <samp>ae</samp> character sequence may be converted to the æ ligature if desired.

is rendered by Netscape as shown in Figure 4-9.

The special HTML reference for the

“ae” ligature entity is

æ and is converted to its appropriate

æ ligature character by most browsers. For more

information, see Appendix F.

The <samp> tag is not used very often. It

should be used in those few cases where special emphasis needs to be

placed on small character sequences taken out of their normal

context.

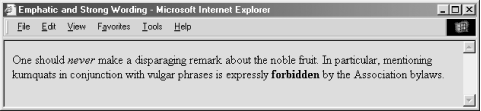

Like

the <em> tag, the

<strong> tag is for emphasizing text, except

with more gusto. Browsers typically display the

<strong> tag differently than the

<em> tag, usually by making the text bold

(versus italic), so that users can distinguish between the two. For

example, in the following text, the emphasized

“never” appears in italic in

Internet Explorer, while the <strong>

“forbidden” is rendered in bold

characters (see Figure 4-10):

One should <em>never</em> make a disparaging remark about the noble fruit. In particular, mentioning kumquats in conjunction with vulgar phrases is expressly <strong>forbidden</strong> by the Association bylaws.

If common sense tells us that the <em> tag

should be used sparingly, the <strong> tag

should appear in documents even more infrequently.

<em> text is like shouting.

<strong> text is nothing short of a scream.

Like a well-chosen epithet voiced by an otherwise taciturn person,

restraint in the use of <strong> makes its

use that much more noticeable and effective.

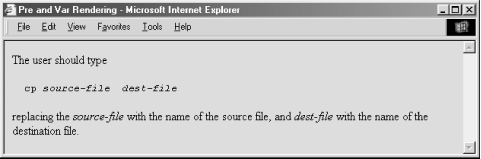

The <var>

tag, another

computer-documentation trick, indicates a variable name or a

user-supplied value. The tag is often used in conjunction with the

<code> and <pre>

tags for displaying particular elements of computer-programming code

samples and the like. Browsers typically render

<var>-tagged text in italics, as shown in

Figure 4-11, which displays Internet

Explorer’s rendering of the following example:

The user should type <pre> cp <var>source-file</var> <var>dest-file</var> </pre> replacing the <var>source-file</var> with the name of the source file, and <var>dest-file</var> with the name of the destination file.

Like the other computer-programming and documentation-related tags,

the <var> tag not only makes it easy for

users to understand and browse your documentation, but automated

systems might someday use the appropriately tagged text to extract

information and useful parameters mentioned in your documents. Once

again, the more semantic information you provide to your browser, the

better it can present that information to the user.

Although each

content-based tag has a default display style, you can override that

style by defining a new look for each tag. This new look can be

applied to the content-based tags using either the

style or class attribute. [Section 8.1.1] [Section 8.3]

You also may assign a unique identifier (id) to

the content-based style tag, as well as a less rigorous

title, using the respective attributes and their

accompanying quote-enclosed string values. [Section 4.1.1.4] [Section 4.1.1.4]

The dir attribute advises the browser which

direction the text within the content-based style tag should be

displayed in, and lang

lets you specify the language used

within the tag. [Section 3.6.1.1] [Section 3.6.1.2]

Things happen in and around a content-based tag’s content, and, with the respective “on” attribute and value, you may react to that event by displaying a user dialog or activating some multimedia event. [Section 12.3.3]

The various graphical browsers render text inside content-based tags in similar fashion; text-only browsers like Lynx have consistent styles for the tags. Table 4-1 summarizes these browsers’ display styles for the native tags. However, style-sheet definitions may override these native display styles.

Table 4-1. Content-based tags

|

Tag |

Netscape |

Internet Explorer |

Lynx |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

italic |

italic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

italic |

italic |

n/a |

|

|

italic |

italic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

bold |

bold |

|

|

|

italic |

italic |

|

Any content-based style tag may contain any item allowed in text, including conventional text, anchors, images, and line breaks. In addition, other content-based and physical style tags can be embedded within the content.

Any content-based style tag may be used anywhere an item allowed in

text is used. In practice, this means you can use the

<em>, <code>, and

other similar tags anywhere in your document except inside

<title>, <listing>,

or <xmp> tagged segments. You can use text

style tags in headings, too, but their effects may be overridden by

the effects of the heading tags themselves.

It may have occurred to you to combine two or more of the various content-based styles to create interesting and perhaps even useful hybrids. Thus, an emphatic citation might be achieved with:

<cite><em>Moby Dick</em></cite>

In practice, Dr. Frankenstein, the browser usually ignores the monster — as you can test by typing and viewing the example yourself, Moby Dick gets the citation without emphasis.

The HTML and XHTML standards do not require the browser to support every possible combination of content-based styles and do not define how the browser should handle such combinations. Someday, maybe. For now, it’s best to choose one tag and be satisfied.

[22] None of the popular browsers format

<code> segments as a text processor might.

Rather, use the <pre> tag in conjunction

with <code> to achieve programming code-like

display effects.

[23] If you need convincing that less is better when applying the content-based and physical style tags, try reading a college textbook in which someone has highlighted what he considered important words and phrases with a yellow marker.

Get HTML & XHTML: The Definitive Guide, 5th Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.