To edit video using iMovie, you must first shoot some video, which is why the first three chapters of this book have nothing to do with your iMovie software. Instead, this book begins with advice on buying and using a digital camcorder, getting to know the equipment, and adopting professional filming techniques. After all, teaching you to edit video without making sure you know how to shoot it is like giving a map to a 16-year-old without first teaching him how to drive.

Technically speaking, you don’t need a camcorder to use iMovie. You can work with QuickTime movies you find on the Web, or use it to turn still photos into slideshows.

But to shoot your own video—and that is the real fun of iMovie—you need a digital camcorder. This is a relatively new camcorder format, one that’s utterly incompatible with the VHS, S-VHS, VHS-C, or 8 mm tapes you may have filled using earlier camcorder types.

iMovie imports video directly from digital camcorders, but that doesn’t mean you can’t use all your older footage; Chapter 4 offers several ways to transfer your older tapes into iMovie. But from this day forward, shoot all of your new footage with a camcorder that takes MiniDV tapes. At this writing, you can buy a MiniDV camcorder for as little as $350. (See the end of this chapter for a DV buying guide.)

Tip

Selling your old camcorder eases much of the pain of buying a DV camcorder. Remember to transfer your old footage into DV format before you do so, however.

A DV camcorder offers enormous advantages over previous formats.

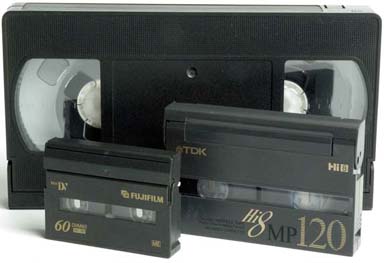

The size of the camcorder is primarily determined by the size of the tapes inside it. A MiniDV cassette (tape cartridge) is tiny, as shown in Figure 1-1, so the camcorders are also tiny.

Figure 1-1. The various sizes of tapes that today’s camcorders can accept differ in size, picture quality, and cost. For both home and prosumer filming, the standard-size VHS cassette (back) is nearly extinct. 8 mm and Hi-8 cassettes (right) are extremely popular among people who don’t have a computer to edit footage, and are very inexpensive. MiniDV tapes (left), like the ones required by most DV camcorders, are more expensive—but the enormous quality improvement makes them worth every penny.

The small size has lots of advantages. You can film surreptitiously when necessary. DV camcorders don’t make kids or interview subjects nervous like bulkier equipment. The batteries last a long time, because they’ve got less equipment to power. And, of course, smaller means it’s easier to take with you.

Still, DV cassettes aren’t perfect. Most hold only 60 or 80 minutes of footage, and they’re more expensive than analog tapes.

As you’ll soon see, however, both of these limitations quickly become irrelevant in the world of iMovie. The whole idea is that iMovie lets you edit your footage and then, if you like, dump it back out to the camcorder. In other words, it’s common iMovie practice to delete the boring footage from DV tape #1, preserve only the good stuff by dumping it onto DV tape #2, and then reuse DV cassette #1 for the next shooting session.

Video quality is measured in lines of resolution: the number of tiny horizontal stripes of color the playback uses to fill your TV screen. As you can see by this table, DV quality blows every previous tape format out of the water. (All camcorders, TVs, and VCRs have the same vertical resolution; this table measures horizontal resolution.)

The sound quality of MiniDV and HDTV is dramatically better than previous formats, too. In fact, it’s better than CD-quality sound, since DV camcorders record sound at 48 kHz instead of 44.1 kHz. (Higher means better.)

Tip

Most DV camcorders offer you a choice of sound-quality modes: 12-bit or 16-bit. The lower quality setting is designed to leave “room” on the tape for adding music after you’ve recorded your video. But avoid it like the plague! If you shoot your video in 12-bit video, your picture will gradually drift out of sync with your audio track—if you plan to save your movie to a DVD. Consult your manual to find out how to switch the camcorder into 16-bit audio mode. Do it before you shoot anything important.

This is a big one. You probably know already that every time you make a copy of VHS footage (or other non-DV material), you lose quality. The copy loses sharpness, color fidelity, and smoothness of color tone. Once you’ve made a copy of a copy, the quality is terrible. Skin appears to have a combination of bad acne and radiation burns, the edges of the picture wobble as though leaking off the glass, and video noise (jiggling static dots) fills the screen. If you’ve ever seen, on the news or America’s Funniest Home Videos, a tape submitted by an amateur camcorder fan, you’ve seen this problem in action.

Digital video is stored on the tape as computer codes, not as pulses of magnetic energy. You can copy this video from DV camcorder to DV camcorder, or from DV camcorder to Mac, dozens of times, making copies of copies of copies. The last generation of digital video will be utterly indistinguishable from the original footage—which is to say, both will look fantastic.

Note

Technically speaking, you can’t keep making copies of copies of a DV tape infinitely. After, say, 20 or 30 generations, you may start to see a few video dropouts (digital-looking specks), depending on the quality of your tapes and duplicating equipment. Still, few people have any reason to make that many copies of copies. (Furthermore, making infinite copies of a single original poses no such problem.)

Depending on how much you read newspapers, you may have remembered the depressing story the New York Times broke in the late eighties: Because home video was such a recent phenomenon at the time, nobody had ever bothered to check out how long videotapes last.

The answer, as it turns out, was: not very long. Depending on storage conditions, the signal on traditional videotapes may begin to fade in as little as ten years! The precious footage of that birth, wedding, or tornado, which you had hoped to preserve forever, could in fact be more fleeting than the memory itself.

Your first instinct might be to rescue a fading video by copying it onto a fresh tape, but making a copy only further damages the footage. The bottom line, said the scientists: There is no way to preserve original video footage forever!

Fortunately, there is now. DV tapes may deteriorate over a decade or two, just as traditional tapes do. But you won’t care. Long before the tape has crumbled, you’ll have transferred the most important material to a new hard drive or a new DV tape or to a DVD. Because quality never degrades when you do so, you’ll glow with the knowledge that your grandchildren and their grandchildren will be able to see your movies with every speck of clarity you see today—even if they have to dig up one of those antique “Macintosh” computers or gigantic, soap-sized “DV camcorders” in order to play it.

As on any camcorder, a DV unit lets you rerecord a scene on top of existing footage. But with DV, at the spot where the new footage begins or ends, you don’t get five seconds of glitchy static, as you do with nondigital camcorders. Instead, you get a clean edit.

The fifth and best advantage of digital video is, of course, iMovie itself. Once you’ve connected your DV or HDTV camcorder up to your Mac (as described in Chapter 4), you can pour the footage from camcorder to computer—and then chop it up, rearrange scenes, add special effects, cut out bad shots, and so on. For the first time in history, it’s simple for anyone, even non-rich people, to edit home movies with professional results. (Doing so in 1990 required a $200,000 Avid editing suite; doing so in 1995 required a $4,000 computer with $4,000 worth of digitizing cards and editing software—and the quality wasn’t great because it wasn’t DV.)

Furthermore, for the first time in history, you won’t have to press the fast-forward button when showing your footage to family, friends, co-workers, and clients. There won’t be any dull footage worth skipping, because you’ll have deleted it on the Mac.

Tip

Before you get nervous about the hours you’ll have to spend editing your stuff in iMovie, remember that there’s no particular law that every video must have crossfades, scrolling credits, and a throbbing music soundtrack. Yes, of course, you can make movies on iMovie that are as slickly produced as commercial films; much of this book is dedicated to helping you achieve that standard. But many people dump an entire DV cassette’s worth of footage onto the Mac, chop out the boring bits, and dump it right back onto the camcorder—only about 20 minutes’ worth of work after the transfer to the Mac.

If you’re reading this book, you probably already have some ideas about what you could do if you could make professional-looking video. Here are a few possibilities that may not have occurred to you. All are natural projects for iMovie:

Home movies. Plain old home movies—casual documentaries of your life, your kids’ lives, your school life, your trips—are the single most popular creation of camcorder owners. Using the suggestions in the following chapters, you can improve the quality of your footage. Using a DV camcorder, you’ll improve the quality of the picture and sound. And using iMovie, you can delete all but the best scenes (and edit out those humiliating parts where you walked for 20 minutes with the camcorder accidentally filming the ground bouncing beneath it).

Actual films. Don’t scoff: iMovie is perfectly capable of creating professional video segments, or even plotted movies. If the amateurs who made The Blair Witch Project or Open Water could do it with their camcorders, you can certainly do it with yours.

Moreover, new film festivals, Web sites, and magazines are springing up everywhere, all dedicated to independent makers of short movies. (More on this topic is coming up in Chapter 13.)

Business videos. It’s very easy to post video on the Internet or burn it onto a cheap, recordable CD or DVD, as described in Part 3. As a result, you should consider video a useful tool in whatever you do. If you’re a realtor, blow away your rivals (and save your clients time) by showing movies, not still photos, of the properties you represent. If you’re an executive, quit boring your comrades with stupefying PowerPoint slides and make your point with video instead.

Once-in-a-lifetime events. Your kid’s school play, your speech, someone’s wedding, someone’s birthday or anniversary party are all worth capturing, especially because now you know that your video can last forever.

Video photo albums. A video photo album can be much more exciting, accessible, and engaging than a paper one. Start by filming or scanning your photos. Assemble them into a sequence, add some crossfades, titles, and music. The result is a much more interesting display than a book of motionless images, thanks in part to iMovie’s Ken Burns effect (Section 9.3). This emerging video form is becoming very popular—videographers are charging a lot of money to create such “living photo albums” for their clients.

Just-for-fun projects. Never again can anyone over the age of eight complain that there’s “nothing to do.” Set them loose with a camcorder and the instruction to make a fake rock video, commercial, or documentary.

Training films. If there’s a better use for video than providing how-to instruction, you’d be hard-pressed to name it. Make a video for new employees to show them the ropes. Make a video that accompanies your product to give a humanizing touch to your company and help the customer make the most of her purchase. Make a tape that teaches newcomers how to play the banjo, grow a garden, kick a football, use a computer program—and market it.

Interviews. You’re lucky enough to live in an age where you can manipulate video just as easily as you do words in a word processor. Capitalize on this fact. Create family histories. Film relatives who still remember the War, the Birth, the Immigration. Or create a time-capsule, time-lapse film: Ask your kid or your parent the same four questions every year on his birthday (such as, “What’s your greatest worry right now?” or “If you had one wish…?” or “Where do you want to be in five years?”). Then, after five or ten or twenty years, splice together the answers for an enlightening fast-forward through a human life.

Broadcast segments. Want a taste of the real world? Call your cable TV company about its public-access channels. (As required by law, every cable company offers a channel or two for ordinary citizens to use for their own programming.) Find out the time and format restraints, and then make a documentary, short film, or other piece for actual broadcast. Advertise the airing to everyone you know. It’s a small-time start, but it’s real broadcasting.

Analyze performances. There’s no better way to improve your golf swing, tennis form, musical performance, or public speaking style than to study footage of yourself. If you’re a teacher, camp counselor, or coach, film your students, campers, or players so that they can benefit from self- analysis, too.

Turn photos into video. Technically, you don’t need a camcorder at all to use iMovie; it’s equally adept at importing and presenting still photos from a scanner or digital camera. In fact, iMovie’s “Ken Burns” effect brings still photos to life, gently zooming into them, fading from shot to shot, panning across them, and so on, making this software the world’s best slideshow creator.

Get iMovie 6 & iDVD: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.