Thousands of people will come to iMovie 6 for the first time, observing that each movie is saved as a single document icon. They’ll go on through life, believing that an iMovie project is a simple, one-icon file, just like a JPEG photo or a Microsoft Word document.

In fact, though, it’s not.

What iMovie creates is not really a document icon. It’s a package icon, which, to Mac OS X aficionados, is code for “a thinly disguised folder.” Yes, it opens up like a document when double-clicked. But if you know what you’re doing, you can open it like a folder instead, and survey the pieces that make up an iMovie movie.

If you don’t know what you’re doing, you can hopelessly mangle your movie. Still, now and then, checking out package contents can get you out of a troubleshooting jam.

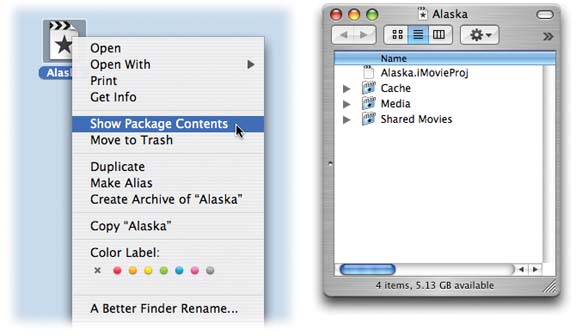

To reveal the contents of this folder-pretending-to-be-a-document, use the Controlkey trick revealed in Figure 4-16.

Figure 4-16. Left: Every new iMovie project “file” is actually a folder. To open it, Controlclick it (or right-click it, if you have a second mouse button). From the shortcut menu, choose Show Package Contents.Right: Inside, the contents look very similar to the contents of an old iMovie project folder, shown in Figure 4-14.

Once you’ve opened up a package into a folder, it looks and works almost exactly like the project folder of older iMovie versions, illustrated in Figure 4-14. Here’s a rundown of the files and folders they have in common.

The actual iMovie project file—called Alaska at right in Figure 4-16—occupies only a few kilobytes of space on the disk, even if it’s a very long movie. Behind the scenes, this document contains nothing more than a list of internal references to the QuickTime clips in the Media folder. Even if you copy, chop, split, rearrange, rename, and otherwise spindle the clips in iMovie, the names and quantity of clips in the Media folder don’t change; all of your iMovie editing, technically speaking, simply shuffles around your project file’s internal pointers to different moments on the clips you originally captured from the camcorder.

The bottom line: If you burn the project document to a CD and take it home to show the relatives for the holidays, you’re in for a rude surprise. It’s nothing without its accompanying Media folder. (And that’s why iMovie now creates a package folder that keeps the document and its media files together.)

Inside the Media folder are several, or dozens, or hundreds of individual QuickTime movies, graphics, and sound files. These represent each clip, sound, picture, or special effect you used in your movie.

Caution

Never rename, move, or delete the files in the Media folder. iMovie will become cranky, display error messages, and forget how you had your movie the last time you opened it.

Do your deleting, renaming, and rearranging in iMovie, not in the Media folder. And above all, don’t take the Media folder (or the project document) out of the package window. Doing so will render your movie uneditable.

(It’s OK to rename the project folder or the project file, however.)

This folder contains two items worth knowing about:

iDVD folder. The reference movie is inside the Shared Movies folder called iDVD. The reference movie for your project bears the same name as the project. For example, if your movie is called Cruise, your Shared Movies → iDVD folder contains a file called Cruise.mov.

Note

As Figure 4-14 makes clear, projects converted from older iMovie versions contain a second reference movie, lying loose in the project folder. It’s an older-style reference movie, left there in case you ever open up the movie in iMovie 4 again for editing.

Technically, this icon is called the reference movie not because you’re supposed to refer to it, but because it contains references (pointers) to all of the individual movie and sound clips in the Media folder, just as the project file does. That’s why the reference movie is so tiny, occupying only a few kilobytes of space.

The reference movie’s primary purpose is to accommodate the direct-to-iDVD movie-burning feature described in Chapter 15. You may occasionally find the reference movie handy for your own purposes, though; it offers a great way to make a quick playback of a movie you’ve been working on. It’s also a convenient “handle” for dragging your iMovie movie into iDVD, Toast Titanium, or other programs that use movies as raw materials.

When you double-click this icon, your iMovie movie appears in QuickTime Player, where a simple tap of the Space bar starts it playing. This method is quicker and less memory-hogging than opening it in iMovie. It’s safer, too, because you don’t risk accidentally nudging some clip or sound file out of alignment; in QuickTime Player, you can’t do anything but watch the movie.

GarageBand. Here’s a wicked-cool new feature of GarageBand—the version that came with your copy of iLife ’06: You can compose a musical soundtrack for an iMovie movie while watching it play in a little window. It’s a no-frills version of actual Hollywood recording sessions, where the conductor leads the orchestra while keeping an eye on the movie playback.

You send the movie off to GarageBand by choosing Share → GarageBand (Chapter 8). At that point, iMovie stashes a version of your movie in this folder—a tiny, low-res version that requires very little Mac horsepower to play. (GarageBand nearly has its hands full just playing back your music.)

Other folders. Using the Share menu is the final step in almost every iMovie project. It’s the last stop on your journey, where you export your masterpiece to another program or medium so it can reach an audience.

The Share-menu commands often hand off your work to some entity beyond itself. For example, when you tell iMovie that you want to burn a DVD, the program hands your work off to iDVD. When you say you want to send the movie to a Bluetooth device (like a cellphone), iMovie hands it off to that wireless gadget.

In each case, iMovie stores the appropriately compressed version of your movie in a temporary folder inside the Shared Movies folder. Here, you’ll find a folder called, for example, iDVD or Bluetooth.

The idea is that if you want to send the same movie out again later, you’ll have a ready-to-transmit copy. You won’t have to wait for iMovie to compress the movie all over again.

This folder is where iMovie stores little scraps and bits it needs for its own use. For example:

The Timeline movie is a lot like the reference movie described above, except that the Timeline.mov movie is primarily for iMovie’s own use. It doesn’t incorporate everything you might consider an important part of the movie (for example, it doesn’t include DVD chapter markers).

Thumbnails.plist and Timeline Movie Data.plist are special data files that store information about the status of your Clips pane (Thumbnails.plist) and the timeline at the bottom of the window (Timeline Movie Data.plist), like what zoom level you’ve selected and whether or not you’ve opted to display sound waves on the audio clips (see the following section). These .plist files are for iMovie’s use, not yours.

Audio waveforms are visual “sound waves” that appear on audio clips. These visible peaks and valleys make it a lot easier to cue up certain video moments with the audio.

These graphic representations of your sound files don’t appear by magic, though. First, you have to turn on this feature by choosing View → Show Clip Volume Levels. Then, iMovie has to compute the waveforms’ shapes, based on the sonic information in each clip.

Because that computational task takes time, iMovie stores a copy of these visuals in the Audio Waveforms folder, which it creates on the fly. Thereafter, each time you open your iMovie project, you won’t have to wait for the waveforms to appear. iMovie will retrieve the information about their shapes from the files in this folder and blast them onto the screen in a matter of moments. (The .wvf files are the waveform graphics; .snp files store “snap to” information for Timeline snapping, as described and illustrated in Section 8.2.)

Get iMovie 6 & iDVD: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.