Recorded music has appeared in a variety of shapes and sizes over the decades, including fragile discs spinning at 78 rpm, vinyl records in colorful sleeves that were artworks in themselves, pocket-size cassette tapes, and futuristic-looking compact discs. But no music format ever exploded into the public consciousness as quickly and widely as the bits of computer code known as MP3 files.

The MP3 format makes it possible to compress a song into a file small enough to be uploaded, downloaded, emailed, and stored on a hard drive. That feat of smallness set off a sonic boom in the late 1990s that continues to reverberate across the music world today.

This chapter tells all about MP3 and other music formats, including the main iPod–approved format: AAC (Advanced Audio Coding), a copy-protected file type that makes Apple’s iTunes Music Store possible.

The era of modern digital audio began in the early 1980s. A new, small, shiny format called the audio compact disc, developed by Sony and Philips, began to appear in music stores alongside albums on tapes and vinyl records. Unlike analog tapes and LPs, audio CDs stored music in digital form, and produced a bright, clean sound with pristine clarity. (Some audiophiles still prefer the “warmer” sound of vinyl, not to mention the expansive canvas that records provided for detailed album artwork, but many have accepted the CD.)

1985 was a pivotal year for the CD. The format’s popularity got a huge boost from its first big seller, Brothers in Arms by Dire Straits, and a variation on the audio CD technology called CD-ROM (Compact Disc, Read-Only Memory) edged into the computer market as a way to play multimedia files and interactive programs.

Over the years, a CD drive became a standard component of a computer. On most audio CDs, songs are stored in a format called CD-DA (Compact Disc, Digital Audio), which is essentially the same thing as AIFF format.

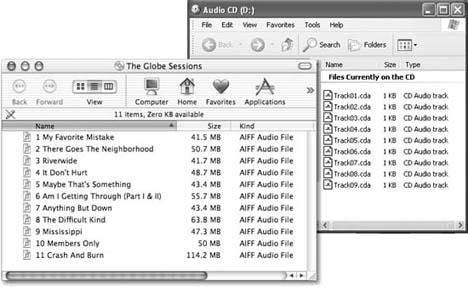

On a Windows PC, if you inspect the contents of a music CD, you see a screenful of names like “Track01.cda.” These turn out to be nothing but 1 KB files that point to the hidden audio tracks, as shown in Figure 4-1. Mac OS X displays the audio tracks in all their hefty glory as AIFF files, right in the Finder window.

Figure 4-1. Left: Here’s what a desktop window looks like for a music CD inserted into a Mac. It looks just like an MP3 playlist, except that these AIFF files are much larger. Your computer can play these high-quality files, but they eat up a lot of hard drive space. Right: Audio files are more bashful when a disc is inserted into a Windows drive. The tracks on this Prince CD remain hidden behind tiny pointer files, and you can lure them out only with CD-extraction software.

Even if you can’t see the audio files, you can still extract them from the CD with software. “Extracting audio tracks” may sound like an uncomfortable medical procedure, but it means copying them from the CD to your hard drive in a computer-readable format. You may also hear the term ripping CDs, which is the same thing.

And while you’re digesting new-millennium terminology: once the music files are on your Mac or PC, you encode them into a compressed audio format like MP3 or AAC so that more music fits on a CD that you burn—or on a music player like the iPod.

Up until a few years ago, the MP3 format was the only game in town for playing quality song files on your computer, whether downloaded from the Internet or taken from CDs. MP3 still dominates the Internet, but other formats—like Ogg Vorbis (an audio format favored by Linux fans and the open source software crowd; details at http://www.vorbis.com)—have dedicated fans, too.

Ogg Vorbis isn’t on the list of iPod–compatible formats, but many others are, including MP3, AAC, AIFF, Apple Lossless, and WAV. Here’s some explanation of each Podworthy format.

Suppose you copy a song from a Sheryl Crow CD directly onto your computer, where it takes up 47.3 MB of hard disk space. (This sort of audio extraction is quick on a Mac, somewhat harder in Windows; see page 84.) Sure, you could now play that song without the CD in your CD drive, but you’d also be out 47.3 megs of precious hard drive real estate (see Figure 4-1).

Now, say you put that Sheryl Crow CD in your computer and use your favorite encoding program to convert that song to an MP3 file. The resulting MP3 file still sounds really good, but only takes up about 4.8 MB of space on your hard drive— about 10 percent of the original. Better yet, you can burn a lot of MP3 files onto a blank CD of your own—up to 11 hours of music on one disc, which is enough to get you from Philadelphia to Columbus on Interstate 70 with tunes to spare.

MP3 files are so small because the compression algorithms use perceptual noise shaping, a method that mimics the ability of the human ear to hear certain sounds. Just as people can’t hear dog whistles, most recorded music contains frequencies that are too high for humans to hear; MP3 compression discards these sounds. Sounds that are blotted out by louder sounds are also cast aside. All of this space-saving by the compression format helps to make a smaller file without overly diminishing the overall sound quality of the music.

New portable MP3 player models come out all the time, but many people consider the iPod’s arrival in 2001 to be a defining moment in the history of MP3 hardware.

The Advanced Audio Coding format may be relatively new (it became official in 1997), but it has a fine pedigree. Scientists at Dolby, Sony, Nokia, AT&T, and those busy folks at Fraunhofer collaborated to come up with a method of squeezing multimedia files of the highest possible quality into the smallest possible space—at least small enough to fit through a modem line. During listening tests, many people couldn’t distinguish between a compressed high-quality AAC file and an original recording.

What’s so great about AAC on the iPod? For starters, the format can do the Big Sound/Small File Size trick even better than MP3. Because of its tighter compression technique, a song encoded in the AAC format sounds better (to most ears, anyway) and takes up less space on the computer than if it were encoded with the same quality settings as an MP3 file. Encoding your files in the AAC format is how Apple says you can stuff 10,000 songs onto a 40 GB iPod.

The AAC format can also be copy protected (unlike MP3), which is why Apple uses it on the iTunes Music Store (see Chapter 7). (The record companies would never have permitted Apple to distribute their property without copy protection.)

Note

You can think of AAC as the Apple equivalent of WMA, the copy-protected Microsoft format used by all online music stores except Apple’s. For better or worse, the iPod doesn’t recognize copy-protected WMA files.

Real Networks, with its own online music store, released a program called Harmony in the summer of 2004 that can convert its WMA wares to an iPod–compatible format and can even wrestle the files onto an iPod without iTunes. Apple released an update for the iPod Photo in late 2004 that disabled this, however, and other members of the iPod family may once again be Real-unfriendly by the time you read this. Apple, of course, would prefer that you do your 99¢-a-song downloading from its iTunes Music Store only (Chapter 7).

Because the iPod can play several different audio formats, you can have a mix of MP3 and AAC files on the device if you want to encode your future CD purchases with the newer format. If you want to read more technical specifications on AAC before deciding, Apple has a page on the format at http://www.apple.com/mpeg4/aac.

Get iPod and iTunes: The Missing Manual, Third Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.