Chapter 1. Introduction

In the next two chapters, I’m going to give you a crash course in XML and constraints. Since there is so much material available on XML and related specifications, I’d rather cruise through this material quickly and get on to Java. For those of you who are completely new to XML, you might want to have a few of the following books around as reference:

XML in a Nutshell, by Elliotte Rusty Harold and W. Scott Means

Learning XML, by Erik Ray

Learning XSLT, by Michael Fitzgerald

XSLT, by Doug Tidwell

These are all O’Reilly books, and I have them scattered about my own workspace. With that said, let’s dive in.

XML 1.0

It all begins with the XML 1.0 Recommendation, which you can read in its entirety at http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-xml. Example 1-1 shows an XML document that conforms to this specification. I’ll use it to illustrate several important concepts.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/"

xmlns="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/" xmlns:admin="http://webns.net/mvcb/"

xmlns:l="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/modules/link/"

xmlns:content="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/modules/content/">

<!--Generated by Blogger v5.0-->

<channel rdf:about="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/journal.asp">

<title>Neil Gaiman's Journal</title>

<link>http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/journal.asp</link>

<description>Neil Gaiman's Journal</description>

<dc:date>2005-04-30T01:57:38Z</dc:date>

<dc:language>en-US</dc:language>

<admin:generatorAgent rdf:resource="http://www.blogger.com/" />

<admin:errorReportsTo rdf:resource="mailto:rss-errors@blogger.com" />

<items>

<rdf:Seq>

<rdf:li

rdf:resource="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/2005/04/three-photographs.asp" />

<rdf:li

rdf:resource="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/2005/04/jetlag-morning.asp" />

<rdf:li

rdf:resource="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/2005/04/demon-days.asp" />

<rdf:li

rdf:resource="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/2005/04/more-from-mailbag.asp" />

<rdf:li

rdf:resource="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/2005/04/two-days.asp" />

<rdf:li

rdf:resource="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/2005/04/finishing-things.asp" />

</rdf:Seq>

</items>

</channel>

<!-- and so on... -->

</rdf:RDF>Tip

For those of you who are curious, this is the RSS feed for Neil Gaiman’s blog (http://www.neilgaiman.com). It uses a lot of RSS syntax, which I’ll cover in Chapter 12 in detail.

A lot of this specification describes what is mostly intuitive. If

you’ve done any HTML authoring, or SGML, you’re already familiar with

the concept of elements (such as items

and channel in Example 1-1) and

attributes (such as resource and content). XML defines how to use these items

and how a document must be structured. XML spends more time defining

tricky issues like whitespace than introducing any concepts that you’re

not at least somewhat familiar with. One exception may be that some of

the elements in Example 1-1 are in

the form:

[prefix]:[element name]

Such as rdf:li. These are

elements in an XML namespace,

something I’ll explain in detail shortly.

An XML document can be broken into two basic pieces: the header, which gives an XML parser and XML applications information about how to handle the document, and the content, which is the XML data itself. Although this is a fairly loose division, it helps us differentiate the instructions to applications within an XML document from the XML content itself, and is an important distinction to understand. The header is simply the XML declaration, in this format:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

This header includes an encoding, and can also indicate whether the document is a standalone document or requires other documents to be referenced for a complete understanding of its meaning:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

The rest of the header is made up of items like the DOCTYPE declaration (not included in the

example):

<!DOCTYPE RDF SYSTEM "DTDs/RDF-gaiman.dtd">

In this case, the declaration refers to a file on the local

system, in the directory DTDs/ called

RDF-gaiman.dtd. Any time you use a relative or

absolute file path or a URL, you want to use the SYSTEM keyword. The other option is using the

PUBLIC keyword, and following it with a

public identifier. This means that the W3C or another

consortium has defined a standard DTD that is associated with that

public identifier. As an example, take the DTD statement for XHTML

1.0:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">

Here, a public identifier is supplied (the funny little string

starting with -//), followed by a

system identifier (the URL). If the public identifier cannot be

resolved, the system identifier is used instead.

You may also see processing instructions at the top of a file, and they are generally considered part of a document’s header, rather than its content. They look like this:

<?xml-stylesheet href="XSL/JavaXML.html.xsl" type="text/xsl"?>

<?xml-stylesheet href="XSL/JavaXML.wml.xsl" type="text/xsl"

media="wap"?>

<?cocoon-process type="xslt"?>Each is considered to have a target (the first word, like xml-stylesheet or cocoon-process) and

data (the rest). Often, the data is in the form

of name-value pairs, which can really help readability. This is only a

good practice, though, and not required, so don’t depend on it.

Other than that, the bulk of your XML document should be content; in other words, elements, attributes, and data that you have put into it.

The Root Element

The root element is the highest-level element in the XML

document, and must be the first opening tag and the last closing tag

within the document. It provides a reference point that enables an XML

parser or XML-aware application to recognize a beginning and end to an

XML document. In Example 1-1, the

root element is RDF:

<rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/"

xmlns="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/" xmlns:admin="http://webns.net/mvcb/"

xmlns:l="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/modules/link/"

xmlns:content="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/modules/content/">

<!-- Document content -->

</rdf:RDF>This tag and its matching closing tag surround all other data content within the XML document. XML specifies that there may be only one root element in a document. In other words, the root element must enclose all other elements within the document. Aside from this requirement, a root element does not differ from any other XML element. It’s important to understand this, because XML documents can reference and include other XML documents. In these cases, the root element of the referenced document becomes an enclosed element in the referring document and must be handled normally by an XML parser. Defining root elements as standard XML elements without special properties or behavior allows document inclusion to work seamlessly.

Elements

So far, I have glossed over defining an actual element. Let’s take an in-depth look at elements, which are represented by arbitrary names and must be enclosed in angle brackets. There are several different variations of elements in the sample document, as shown here:

<!-- Standard element opening tag -->

<items>

<!-- Standard element with attribute -->

<rdf:li

rdf:resource="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/2005/04/three-photographs.asp">

<!-- Element with textual data -->

<dc:creator>Neil Gaiman</dc:creator>

<!-- Empty element -->

<l:permalink l:type="text/html"

rdf:resource="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/2005/04/finishing-things.asp"

/>

<!-- Standard element closing tag -->

</items>Tip

This isn’t actual XML; it’s just a collection of examples. Trying to parse something like this would fail, as there are opening tags without corresponding closing tags.

The first rule in creating elements is that their names must start with a letter or underscore, and then may contain any amount of letters, numbers, underscores, hyphens, or periods. They may not contain embedded spaces:

<!-- Embedded spaces are not allowed --> <my element name>

XML element names are also case-sensitive. Generally, using the same rules that

govern Java variable naming will result in sound XML element naming.

Using an element named tcbo to

represent Telecommunications Business

Object is not a good idea because it is cryptic, while an

overly verbose tag name like beginningOfNewChapter just clutters up a

document. Keep in mind that your XML documents will probably be seen

by other developers and content authors, so clear documentation

through good naming is essential.

Every opened element must in turn be closed. There are no exceptions

to this rule as there are in many other markup languages, like HTML.

An ending element tag consists of the forward slash and

then the element name: </items>. Between an opening and

closing tag, there can be any number of additional elements or textual

data. However, you cannot mix the order of nested tags; the first opened element must always be the

last closed element. If any of the rules for XML syntax are not

followed in an XML document, the document is not well-formed. A well-formed document is one in

which all XML syntax rules are followed, and all elements and

attributes are correctly positioned. However, a well-formed document

is not necessarily valid, which means that it follows the

constraints set upon a document by its DTD or schema. There is a significant difference between

a well-formed document and a valid one; the rules I discuss in this

section ensure that your document is well-formed, while the rules

discussed in Chapter

2 ensure that your document is valid.

As an example of a document that is not well-formed, consider this XML fragment:

<tag1> <tag2> </tag1> </tag2>

The order of nesting of tags is incorrect, as the opened

<tag2> is not followed by a

closing </tag2> within the

surrounding tag1 element. However,

even if these syntax errors are corrected, there is still no guarantee

that the document will be valid.

While this example of a document that is not well-formed may seem trivial, remember that this would be acceptable HTML, and commonly occurs in large tables within an HTML document. In other words, HTML and many other markup languages do not require well-formed XML documents. XML’s strict adherence to ordering and nesting rules allows data to be parsed and handled much more quickly than when using markup languages without these constraints.

The last rule I’ll look at is the case of empty elements. I already said that XML tags must always be paired; an opening tag and a closing tag constitute a complete XML element. There are cases where an element is used purely by itself, like a flag stating a chapter is incomplete, or where an element has attributes but no textual data, like an image declaration in HTML. These would have to be represented as:

<admin:generatorAgent rdf:resource="http://www.blogger.com/"> </admin:generatorAgent> <img src="/images/xml.gif"></img>

This is obviously a bit silly, and adds clutter to what can often be very large XML documents. The XML specification provides a means to signify both an opening and closing element tag within one element:

<admin:generatorAgent rdf:resource="http://www.blogger.com/" /> <img src="/images/xml.gif" />

Attributes

In addition to text contained within an element’s tags, an

element can also have attributes. Attributes are included with their

respective values within the element’s opening declaration (which can

also be its closing declaration!). For example, in the channel element, a URL for information about

the channel is noted in an attribute:

<channel rdf:about="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/journal.asp">

In this example, rdf:about is

the attribute name; the value is the URL, "http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/journal.asp".

Attribute names must follow the same rules as XML element names,

and attribute values must be within quotation marks. Although both single and double quotes

are allowed, double quotes are a widely used standard and result in

XML documents that model Java programming practices.

In addition to learning how to use attributes, there is an issue

of when to use attributes. Because XML allows such a variety of data

formatting, it is rare that an attribute cannot be represented by an

element, or that an element could not easily be converted to an

attribute. Although there’s no specification or widely accepted

standard for determining when to use an attribute and when to use an

element, there is a good rule of thumb: use elements for

multiple-valued data and attributes for single-valued data. If data

can have multiple values, or is very lengthy, the data most likely

belongs in an element. It can then be treated primarily as textual

data, and is easily searchable and usable. Examples are the

description of a book’s chapters, or URLs detailing related links from

a site. However, if the data is primarily represented as a single

value, it is best represented by an attribute. A good candidate for an

attribute is the section of a chapter; while the section item itself

might be an element and have its own title, the grouping of chapters

within a section could be easily represented by a section attribute within the chapter element. This attribute would allow

easy grouping and indexing of chapters, but would never be directly

displayed to the user. Another good example of a piece of data that

could be represented in XML as an attribute is if a particular table

or chair is on layaway. This instruction could let an XML application

used to generate a brochure or flyer know to not include items on

layaway in current stock; obviously this is a true or false value, and

has only a singular value at any time. Again, the application client

would never directly see this information, but the data would be used

in processing and handling the XML document. If after all of this

analysis you are still unsure, you can always play it safe and use an

element.

Namespaces

Note the use of namespaces in the root element of Example 1-1:

<rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/"

xmlns="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/" xmlns:admin="http://webns.net/mvcb/"

xmlns:l="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/modules/link/"

xmlns:content="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/modules/content/">An XML namespace is a means of associating

one or more elements in an XML document with a particular URI. This means that the element is identified by both

its name and its namespace URI. In many complex

XML documents, the same XML name (for example, author) may need to be used in different

ways. For instance, in the example, there is an author for the RSS

feed, as well as an author for each journal entry. While both of these

pieces of data fit nicely into an element named author, they should not be taken as the same

type of data.

The XML namespaces specification nicely solves this problem. The

namespace specification requires that a unique URI be associated with

a prefix to distinguish the elements in one namespace from

elements in other namespaces. So you could assign a URI of http://www.neilgaiman.com/entries, and

associate it with the prefix journal, for use by journal-specific

elements. You could then assign another URI, like http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns,

and a prefix of rss, for

RSS-specific elements:

<rdf:RDF xmlns:rss="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:journal="http://www.neilgaiman.com/entries">Now you can use those prefixes in your XML:

<rss:author>Doug Hally</rss:author> <journal:author>Neil Gaiman</journal:author>

Tip

You can actually use a namespace prefix on the same element where that namespace is declared. For example, this is perfectly legal XML:

<rss:author xmlns:rss="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#">Doug Hally</rss:author>

An XML parser can now easily distinguish these two different

types of author; as an added

benefit, the XML is a lot more human-readable now.

Entity References

One item I have not discussed is escaping characters, or referring to other constant type data

values. For example, a common way to represent a path to an

installation directory in online documentation is <path-to-Ant> or <TOMCAT_HOME>. Here, the user would

replace the text with the appropriate choice of installation

directory. In the following journal entry, there are several HTML tags

within the entry itself:

When the shoot was done, my daughter Holly, who had been doing her homework in the room next door, and occasionally coming out to laugh at me, helped use up the last few pictures on the roll. She looks like she's having fun. I think I look a little dazed.<br /><br /><imgsrc="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/Neil_8313036.jpg"><br /><br />This is the one we're going to be using on the book jacket of ANANSI BOYS.

The problem is that XML parsers attempt to handle these bits of

data (<br /> and <img>) as XML tags. This is a common

problem, as any use of angle brackets results in this behavior. Entity references provide a way to overcome

this problem. An entity reference is a special data type in XML used

to refer to another piece of data. The entity reference consists of a

unique name, preceded by an ampersand and followed by a semicolon: &

[entity name] ;. When an XML parser sees an entity

reference, the specified substitution value is inserted, and no

processing of that value occurs. XML defines five entities to address

the problem discussed in the example: < for the less-than bracket, > for the greater-than bracket,

& for the ampersand sign

itself, " for a double quotation mark, and

' for a single quotation mark or

apostrophe. Using these special references, the entry can contain the

HTML tags without having them interpreted as XML tags by the XML

parser:

When the shoot was done, my daughter Holly, who had been doing her homework in the room next door, and occasionally coming out to laugh at me, helped use up the last few pictures on the roll. She looks like she's having fun. I think I look a little dazed.<br /><br /><img src="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/Neil_8313036.jpg" /><br /><br />This is the one we're going to be using on the book jacket of ANANSI BOYS.

Once this document is parsed, the data is interpreted as normal

HTML br and img tags, and the document is still

considered well-formed.

Also be aware that entity references are user-definable. This allows a sort of shortcut markup; for example, you might want to reference a copyright notice online somewhere. Because the copyright is used for multiple books and articles, it doesn’t make sense to include the actual text within hundreds of different XML documents; however, if the copyright is changed, all referring XML documents should reflect the changes:

<ora:copyright>&OReillyCopyright;</ora:copyright>

Although you won’t see how the XML parser is told what to

reference when it sees &OReillyCopyright; until the next

chapter, you need to realize that there are more uses for entity

references than just representing difficult or unusual characters

within data.

Unparsed Data

The last XML construct to look at is the CDATA section marker. A CDATA section is used when a significant

amount of data should be passed on to the calling application without

any XML parsing. It is used when an unusually large number of

characters would have to be escaped using entity

references, or when spacing must be preserved. In an XML document, a

CDATA section looks like

this:

<content:encoded><![CDATA[Lot of flying yesterday and now I'm home again. For a day. Last night's useful post was written, but was eaten by weasels. Next week is the last week of <em>Beowulf-</em>with-Avary-and-Zemeckis work for a long while, and then I get to be home for about a month, if you don't count the trip to New York for Book Expo, and right now I just like the idea of sleeping in my own bed for a couple of nights running. <br /><br /> </p>]]></content:encoded>

In this example, the information within the CDATA section does not have to use entity

references or other mechanisms to alert the parser that reserved

characters are being used; instead, the XML parser passes them

unchanged to the wrapping program or application.

At this point, you have seen the major components of XML documents. Although each has only been briefly described, this should give you enough information to recognize the parts of an XML document when you see them and know their general purpose.

XML 1.1

In February of 2004, the XML 1.1 specification was released by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C; http://www.w3.org). If you don’t recall hearing much about XML 1.1, it’s no surprise; XML 1.1 was largely about Unicode conformance, and really didn’t affect XML as a whole that much, particularly for document authors and programmers not working with unusual character sets.

While XML was undergoing fairly minor maintenance updates, Unicode moved from Version 2.0 to 4.0. Since XML relies on Unicode for the characters allowed in XML element and attribute names, this had a ripple effect on document authors who wanted to use the new Unicode 4.0 characters in their documents. In XML 1.0, the specification had to explicitly permit characters to be in element and attribute names; as a result, new characters in later versions of Unicode were excluded for name usage by parsers. In XML 1.1—in an effort to avoid similar problems in the future—characters not explicitly forbidden are permitted. This means that if new characters are added in future Unicode versions, they can immediately be used in XML 1.1 documents.

If all of this doesn’t mean anything to you, then you probably

don’t need to be too concerned about XML 1.1. Personally, I still type

in version="1.0" and haven’t needed

to change that yet. If you want to understand more about the intricacies

of Unicode and XML 1.1, check out the complete specification at

http://www.w3.org/TR/xml11.

Tip

All the tools and parsers used throughout this book will work with XML 1.0 and 1.1 documents.

XML Transformations

One of the cooler things about XML is the ability to transform it into something else. With the wealth of web-capable devices these days (computers, personal organizers, phones, DVRs, etc.), you never know what flavor of markup you need to deliver. Sometimes HTML works, sometimes XHTML (the XML flavor of HTML) is required, sometimes the Wireless Markup Language (WML) is supported; and sometimes you need something else entirely. In all of these cases, though, the basic data being displayed is the same; it’s just the formatting and presentation that changes. A great technique is to store the data in an XML document, and then transform that XML into various formats for display.

As useful as XML transformations can be, though, they are not simple to implement. In fact, rather than trying to specify the transformation of XML in the original XML 1.0 specification, the W3C has put out three separate recommendations to define how XML transformations work.

Because these three specifications are tied together tightly and are almost always used in concert, there is rarely a clear distinction between them. This can often make for a discussion that is easy to understand, but not necessarily technically correct. In other words, the term XSLT, which refers specifically to extensible stylesheet transformations, is often applied to both XSL and XPath. In the same fashion, XSL is often used as a grouping term for all three technologies. In this section, I distinguish among the three recommendations, and remain true to the letter of the specifications outlining these technologies. However, in the interest of clarity, I use XSL and XSLT interchangeably to refer to the complete transformation process throughout the rest of the book. Although this may not follow the letter of these specifications, it certainly follows their spirit, as well as avoiding lengthy definitions of simple concepts when you already understand what I mean.

XSL

XSL is the Extensible Stylesheet Language. It is defined as a language for expressing stylesheets. This broad definition is broken down into two parts:

XSL is a language for transforming XML documents.

XSL is an XML vocabulary for specifying the formatting of XML documents.

The definitions are similar, but one deals with moving from one XML document form to another, while the other focuses on the actual presentation of content within each document. Perhaps a clearer definition would be to say that XSL handles the specification of how to transform a document from format A to format B. The components of the language handle the processing and identification of the constructs used to do this.

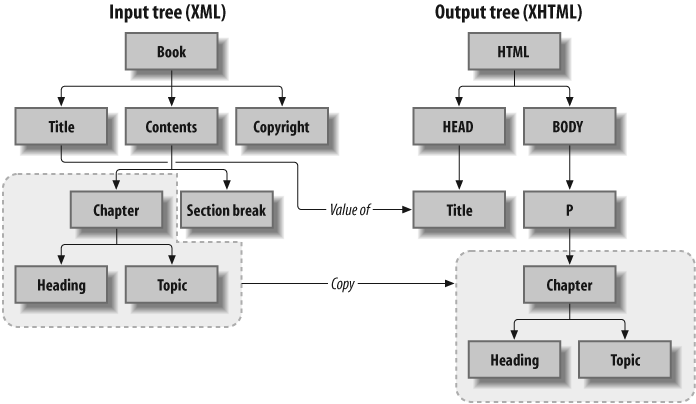

XSL and trees

The most i mportant concept to understand in XSL is that all data within XSL processing stages is in tree structures (see Figure 1-1). In fact, the rules you define using XSL are themselves held in a tree structure. This allows simple processing of the hierarchical structure of XML documents. Templates are used to match the root element of the XML document being processed. Then “leaf” rules are applied to “leaf” elements, filtering down to the most nested elements. At any point in this progression, elements can be processed, styled, ignored, copied, or have a variety of other things done to them.

A nice advantage of this tree structure is that it allows the grouping of XML documents to be maintained. If element A contains elements B and C, and element A is moved or copied, the elements contained within it receive the same treatment.

This makes the handling of large data sections that need to receive the same treatment fast and easy to notate concisely in the XSL stylesheet. You will see more about how this tree is constructed when I talk specifically about XSLT in the next section.

Formatting objects

The XSL specification is almost entirely concerned with defining formatting objects. A formatting object is based on a large model, not surprisingly called the formatting model. This model is all about a set of objects that are fed as input into a formatter. The formatter applies the objects to the document, and what results is a new document that consists of all or part of the data from the original XML document in a format specific to the objects the formatter used. Because this is such a vague, shadowy concept, the XSL specification attempts to define a concrete model to which these objects should conform. In other words, a large set of properties and vocabulary make up the set of features that formatting objects can use. These include the types of areas that may be visualized by the objects; the properties of lines, fonts, graphics, and other visual objects; inline and block formatting objects; and a wealth of other syntactical constructs.

Formatting objects are used heavily when converting textual XML data into binary formats such as PDF files, images, or document formats such as Microsoft Word. For transforming XML data to another textual format, these objects are seldom used explicitly. Although an underlying part of the stylesheet logic, formatting objects are rarely invoked directly, since the resulting textual data often conforms to another predefined markup language such as HTML. Because most enterprise applications today are based at least in part on web architecture and use a browser as a client, I spend the most time looking at transformations to HTML and XHTML. While formatting objects are covered only lightly, the topic is broad enough to merit its own coverage in a separate book. For further information, consult the XSL specification at http://www.w3.org/TR/xsl.

XSLT

The second component of XML transformations is XSL Transformations. XSLT is the language that specifies the conversion of a document from one format to another (where XSL defined the means of that specification). The syntax used within XSLT is generally concerned with textual transformations that do not result in binary data output. For example, XSLT is instrumental is generating HTML or WML from an XML document. In fact, the XSLT specification outlines the syntax of an XSL stylesheet more explicitly than the XSL specification itself!

Just as in the case of XSL, an XSLT stylesheet is always well-formed, valid XML. A DTD is defined for XSL and XSLT that delineates the allowed constructs. For this reason, you should only have to learn new syntax to use XSLT, and not new structural rules (if you know how XML is structured, you know how XSLT is structured). Just as in XSL, XSLT is based on a hierarchical tree structure of data, where nested elements are leaves, or children, of their parents. XSLT provides a mechanism for matching patterns within the original XML document, and applying formatting to that data. This results in anything from outputting XML data without the unwanted element names to inserting the data into a complex HTML table and displaying it to the user with highlighting and coloring. XSLT also provides syntax for many common operators, such as conditionals, copying of document tree fragments, advanced pattern matching, and the ability to access elements within the input XML data in an absolute and relative path structure. All these constructs are designed to ease the process of transforming an XML document into a new format.

XPath

As the final piece of the XML transformations puzzle, XPath provides a mechanism for referring to the wide variety of element and attribute names and values in an XML document. As I mentioned earlier, many XML specifications are now using XPath, but this discussion is concerned primarily with its use in XSLT. With the complex structure that an XML document can have, locating one specific element or set of elements can be difficult. It is made more difficult because access to a set of constraints that outlines the document’s structure cannot be assumed; documents that are not validated must be able to be transformed just as valid documents can. To accomplish this addressing of elements, XPath defines syntax in line with the tree structure of XML, and the XSLT processes and constructs that use it.

Referencing any element or attribute within an XML document is most easily accomplished by specifying the path to the element relative to the current element being processed. In other words, if element B is the current element and element C and element D are nested within it, a relative path most easily locates them. This is similar to the relative paths used in operating system directory structures. At the same time, XPath also defines addressing for elements relative to the root of a document. This covers the common case of needing to reference an element not within the current element’s scope; in other words, an element that is not nested within the element being processed. Finally, XPath defines syntax for actual pattern matching: find an element whose parent is element E and that has a sibling element F. This fills in the gaps left between the absolute and relative paths. In all these expressions, attributes can be used as well, with similar matching abilities:

<!-- Match the element named link underneath the current element --> <xsl:value-of select="link" /> <!-- Match the element named title nested within the channel element --> <xsl:value-of select="channel/title" /> <!-- Match the description element using an absolute path --> <xsl:value-of select="/rdf:RDF/description" /> <!-- Match the resource attribute of the current element --> <xsl:value-of select="@rdf:resource" /> <!-- Match the resource attribute of the errorReportsTo element --> <xsl:value-of select="/rdf:RDF/channel/admin:errorReportsTo/@rdf:resource" />

Because the input document is often not fixed, an XPath expression can result in the evaluation of no input data, one input element or attribute, or multiple input elements and attributes. This ability makes XPath very useful and handy; it also causes the introduction of some additional terms. The result of evaluating an XPath expression can be a node set. This name is in line with the idea of a hierarchical structure, which is dealt with in terms of leaves and nodes. The resultant node set can be empty, have a single member, or have 5 or 10 members. It can be transformed, copied, ignored, or have any other legal operation performed on it. Instead of a node set, evaluating an XPath expression could result in a Boolean value, a numerical value, or a string value.

In addition to expressions that select node sets, XPath defines several functions that operate on node

sets, like not() and count(). These functions take in a node

set as input and operate upon that node set. All of these expressions

and functions are part of the XPath specification and XPath

implementations; however, XPath is also often used to signify any

expression that conforms to the specification itself. As with XSL and

XSLT, this makes it easier to talk about XSL and XPath, though it is

not always technically correct.

With all that in mind, you’re at least somewhat prepared to take a look at a simple XSL stylesheet, shown in Example 1-2.

<?xml version="1.0" ?>

<xsl:stylesheet xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform" version="1.0"

xmlns:rss="http://purl.org/rss/1.0/"

xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/"

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#">

<xsl:output method="xml" omit-xml-declaration="yes" indent="yes"/>

<xsl:template match="/rdf:RDF">

<p>

<a><xsl:attribute name="href">

<xsl:value-of select="rss:channel/rss:link"/>

</xsl:attribute>

<xsl:value-of select="rss:channel/rss:title"/></a>

</p>

<p>

<!-- Make the date presentable -->

<xsl:variable name="datetime" select="rss:channel/dc:date"/>

<xsl:variable name="day" select="substring($datetime, 9, 2)"/>

<xsl:variable name="month" select="substring($datetime, 6, 2)"/>

<xsl:variable name="year" select="substring($datetime, 0, 5)"/>

<xsl:value-of select="concat($day, '/', $month, '/', $year)"/> -

<xsl:value-of select="substring($datetime, 12, 5)"/>

</p>

<dl>

<xsl:for-each select="rss:item">

<dt>

<a><xsl:attribute name="href">

<xsl:value-of select="rss:link"/>

</xsl:attribute>

<xsl:value-of select="rss:title"/></a>

</dt>

<dd>

<xsl:value-of select="rss:description"

disable-output-escaping="yes" />

<!-- Format the publish date -->

(<xsl:variable name="pubdate" select="dc:date"/>

<xsl:variable name="pubday" select="substring($pubdate, 9, 2)"/>

<xsl:variable name="pubmonth" select="substring($pubdate, 6, 2)"/>

<xsl:variable name="pubyear" select="substring($pubdate, 0, 5)"/>

<xsl:value-of select="concat($pubday, '/', $pubmonth, '/', $pubyear)"/> -

<xsl:value-of select="substring($pubdate, 12, 5)"/>)

</dd>

</xsl:for-each>

</dl>

<p>

<xsl:value-of select="rss:channel/dc:rights"/>

</p>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>Template matching

The basis of all XSL work is template matching. For any element on

which you want some sort of output to occur, you generally provide a

template that matches the element. You signify a template with the

template keyword, and provide the name of

the element to match in its match attribute:

<xsl:template match="/rdf:RDF">

<p>

<a><xsl:attribute name="href">

<xsl:value-of select="rss:channel/rss:link"/>

</xsl:attribute>

<xsl:value-of select="rss:channel/rss:title"/></a>

</p>

<!-- etc... -->

</xsl:template>Here, the RDF element (in

the rdf-associated namespace) is

being matched (the / is an XPath

construct). When an XSL processor encounters the RDF element, the instructions within this

template are carried out. In the example, several HTML formatting

tags are output (the p and

a tags). Be sure to distinguish

your XSL elements from other elements (such as HTML elements)

with proper use of namespaces.

You can use the value-of construct to obtain the value of an

element, and provide the element name to match through the select attribute. In the example, the

character data within the title

element is extracted and used as the title of the page, and a link

is constructed using the link

element as the target.

On the other hand, when you want to cause the templates

associated with an element’s children to be applied, use apply-templates. Be sure to do this, or

nested elements can be ignored! You can specify the

elements to apply templates to using the

select attribute; by specifying a value of

* to that attribute, all

templates left will be applied to all nested elements.

Looping

You’ll also often find a need for looping in XSL:

<xsl:for-each select="rss:item">

<dt>

<a><xsl:attribute name="href">

<xsl:value-of select="rss:link"/></xsl:attribute>

<xsl:value-of select="rss:title"/></a>

</dt>

<dd>

<xsl:value-of select="rss:description"

disable-output-escaping="yes" />

<!-- Format the publish date -->

(<xsl:variable name="pubdate" select="dc:date"/>

<xsl:variable name="pubday" select="substring($pubdate, 9, 2)"/>

<xsl:variable name="pubmonth" select="substring($pubdate, 6, 2)"/>

<xsl:variable name="pubyear" select="substring($pubdate, 0, 5)"/>

<xsl:value-of select="concat($pubday, '/', $pubmonth, '/', $pubyear)"/> -

<xsl:value-of select="substring($pubdate, 12, 5)"/>)

</dd>

</xsl:for-each>Here, I’m looping through each element named item using the

for-each construct. In Java, this would be:

for (Iterator i = item.iterator(); i.hasNext( ); ) {

// take action on each item

}Within the loop, the “current” element becomes the next

item element encountered. For

each item, I output the description (the entry text) using the

value-ofconstruct. Take

particular note of the disable-output-escaping attribute. In the

XML, the description element has

HTML content, which makes liberal use of entity references:

When the shoot was done, my daughter Holly, who had been doing her homework in the room next door, and occasionally coming out to laugh at me, helped use up the last few pictures on the roll. She looks like she's having fun. I think I look a little dazed.<br /><br /><img src="http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/Neil_8313036.jpg" /><br /><br />This is the one we're going to be using on the book jacket of ANANSI BOYS.

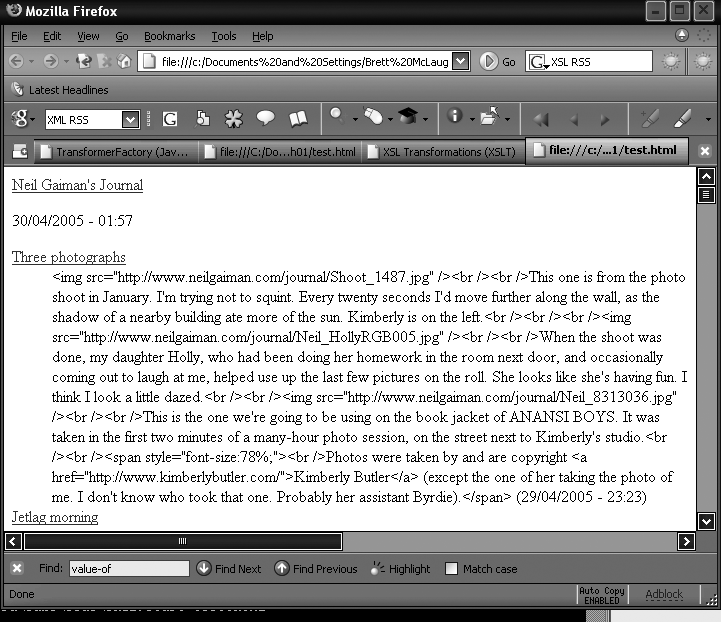

Normally, value-of outputs

text just as it is in the XML document being processed. The result

would be that this escaped HTML would stay escaped. The output

document would end up looking like Figure 1-2.

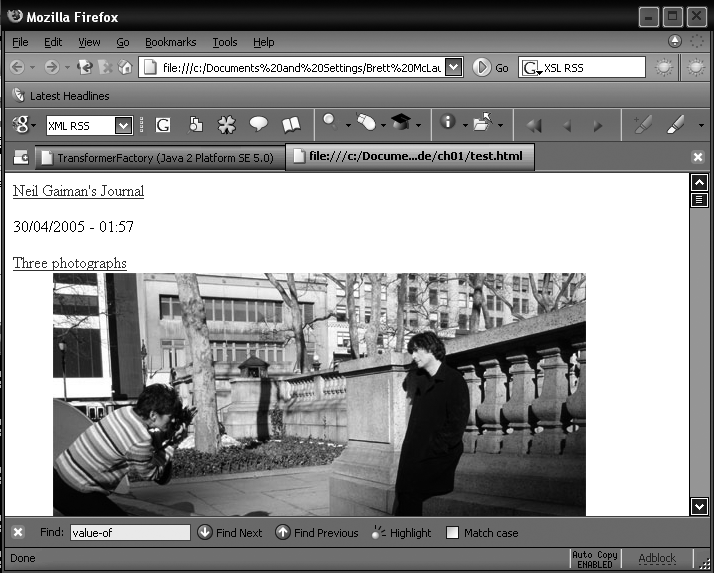

To ensure that your output is not escaped, set disable-output-escaping to yes.

Tip

Be sure you think this through. I used to get confused,

thinking that I wanted to set this attribute to no so that escaping would

not happen. However, a value of no results in escaping being enabled

(not being disabled). Make sure you get this straight, or you’ll

have some odd results.

Setting this attribute to yes and rerunning the transform results in

the output shown in Figure 1-3.

Performing a transform

Before leaving XSL (at least for now), I want to show you how to easily perform transformations from the command line. This is a useful tool for quick-and-dirty tests; in fact, it’s how I generated the screenshots used in this chapter.

Download Xalan-J from the Xalan web site, http://xml.apache.org/xalan-j. Expand the archive (on my Windows laptop, I use c:/java/xalan-j_2_6_0).

Then add xalan.jar, xercesImpl.jar, and xml-apis.jar to your classpath. Finally, run the following command:

java org.apache.xalan.xslt.Process –IN[XML filename]-XSL[XSL stylesheet]-OUT[output filename]

For example, to generate the HTML output for Neil Gaiman’s feed, I used the tool like this:

>java org.apache.xalan.xslt.Process -IN gaiman-blogger_rss.xml-XSL rdf.xsl -OUT test.html

You’ll get a file (test.html in this case) in the directory in which you run the command. Use this tool often; it will really help you figure out how XSL works, and what effect small changes have on output.

And More...

Lest I mislead you into thinking that’s all that there is to XML, I want to make sure that you realize there are a multitude of other XML-related technologies. I can’t possibly get into them all in this chapter, or even in this book. You should take a quick glance at things like Cascading Style Sheets ( CSS) and XHTML if you are working on web design. Document authors will want to find out more about XLink and XPointer. XQuery will be of interest to database programmers. In other words, there’s something XML for pretty much every technology space right now. Take a look at the W3C XML activity page at http://www.w3.org/XML and see what looks interesting.

Get Java and XML, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.