This book has 17 chapters that are divided into four parts, plus two appendixes.

- Chapter 1

Chapter 1 introduces the basic architecture and design of the

java.iopackage, including the reader/stream dichotomy. Some basic preliminaries about theint,byte, andchardata types are discussed. TheIOExceptionthrown by many I/O methods is introduced. The console is introduced, along with some stern warnings about its proper use. Finally, I offer a cautionary message about how the security manager can interfere with most kinds of I/O, sometimes in unexpected ways.- Chapter 2

Chapter 2 teaches you the basic methods of the

java.io.OutputStreamclass you need to write data onto any output stream. You’ll learn about the three overloaded versions ofwrite(), as well asflush()andclose(). You’ll see several examples, including a simple subclass ofOutputStreamthat acts like/dev/nulland aTextAreacomponent that gets its data from an output stream.- Chapter 3

The third chapter introduces the basic methods of the

java.io.InputStreamclass you need to read data from a variety of sources. You’ll learn about the three overloaded variants of theread()method and when to use each. You’ll see how to skip over data and check how much data is available, as well as how to place a bookmark in an input stream, then reset back to that point. You’ll learn how and why to close input streams. This will all be drawn together with aStreamCopierprogram that copies data read from an input stream onto an output stream. This program will be used repeatedly over the next several chapters.

- Chapter 4

The majority of I/O involves reading or writing files. Chapter 4 introduces theFileInputStreamandFileOutputStreamclasses, concrete subclasses ofInputStreamandOutputStreamthat let you read and write files. These classes have all the usual methods of their superclasses, such asread(),write(),available(),flush(), and so on. Also in this chapter, development of a File Viewer program commences. You’ll see how to inspect the raw bytes in a file in both decimal and hexadecimal format. This example will be progressively expanded throughout the rest of the book.- Chapter 5

From its first days, Java has always had the network in mind, more so than any other common programming language. Java is the first programming language to provide as much support for network I/O as it does for file I/O, perhaps even more. Chapter 5 introduces Java’s

URL,URLConnection,Socket, andServerSocketclasses, all fertile sources of streams. Typically the exact type of the stream used by a network connection is hidden inside the undocumentedsunclasses. Thus network I/O relies primarily on the basicInputStreamandOutputStreammethods. Examples in this chapter include several simple web and email clients.

- Chapter 6

Chapter 6 introduces filter streams. Filter input streams read data from a preexisting input stream like a

FileInputStream, and have an opportunity to work with or change the data before it is delivered to the client program. Filter output streams write data to a preexisting output stream such as aFileOutputStream, and have an opportunity to work with or change the data before it is written onto the underlying stream. Multiple filters can be chained onto a single underlying stream to provide the functionality offered by each filter. Filters streams are used for encryption, compression, translation, buffering, and much more. At the end of this chapter, the File Viewer program is redesigned around filter streams to make it more extensible.- Chapter 7

Chapter 7 introduces data streams, which are useful for writing strings, integers, floating-point numbers, and other data that’s commonly presented at a level higher than mere bytes. The

DataInputStreamandDataOutputStreamclasses read and write the primitive Java data types (boolean,int,double, etc.) and strings in a particular, well-defined, platform-independent format. SinceDataInputStreamandDataOutputStreamuse the same formats, they’re complementary. What a data output stream writes, a data input stream can read, and vice versa. These classes are especially useful when you need to move data between platforms that may use different native formats for integers or floating-point numbers. Along the way, you’ll develop classes to read and write little-endian numbers, and you’ll extend the File Viewer program to handle big- and little-endian integers and floating-point numbers of varying widths.- Chapter 8

Chapter 8 shows you how streams can move data from one part of a running Java program to another. There are three main ways to do this. Sequence input streams chain several input streams together so that they appear as a single stream. Byte array streams allow output to be stored in byte arrays and input to be read from byte arrays. Finally, piped input and output streams allow output from one thread to become input for another thread.

- Chapter 9

Chapter 9 explores the

java.util.zipandjava.util.jarpackages. These packages contain assorted classes that read and write data in zip, gzip, and inflate/deflate formats. Java uses these classes to read and write JAR archives and to display PNG images. However, thejava.util.zipclasses are more general than that, and can be used for general-purpose compression and decompression. Among other things, they make it trivial to write a simple compressor or decompressor program, and several will be demonstrated. In the final example, support for compressed files is added to the File Viewer program.- Chapter 10

The Java core API contains two cryptography-related filter streams in the

java.securitypackage,DigestInputStreamandDigestOutputStream. There are two more in thejavax.cryptopackage,CipherInputStreamandCipherOutputStream, available in the Java Cryptography Extension™ (JCE for short). Chapter 10 shows you how to use these classes to encrypt and decrypt data using a variety of algorithms, including DES and Blowfish. You’ll also learn how to calculate message digests for streams that can be used for digital signatures. In the final example, support for encrypted files is added to the File Viewer program.

- Chapter 11

The first 10 chapters showed you how to read and write various primitive data types to many different kinds of streams. Chapter 11 shows you how to write everything else. Object serialization, first used in the context of remote method invocation (RMI) and later for JavaBeans™, lets you read and write almost arbitrary objects onto a stream. The

ObjectOutputStreamclass provides awriteObject()method you can use to write a Java object onto a stream. TheObjectInputStreamclass has areadObject()method you can use to read an object from a stream. In this chapter, you’ll learn how to use these two classes to read and write objects, as well as how to customize the format used for serialization.- Chapter 12

Chapter 12 shows you how to perform operations on files other than simply reading or writing them. Files can be moved, deleted, renamed, copied, and manipulated without respect to their contents. Files are also often associated with meta-information that’s not strictly part of the contents of the file, such as the time the file was created, the icon for the file, or the permissions that determine which users can read or write to the file.

The

java.io.Fileclass attempts to provide a platform-independent abstraction for common file operations and meta-information. Unfortunately, this class really shows its Unix roots. It works fine on Unix, reasonably well on Windows—with a few caveats—and fails miserably on the Macintosh. File manipulation is thus one of the real bugbears of cross-platform Java programming. Therefore, this chapter shows you not only how to use theFileclass, but also the precautions you need to take to make your file code portable across all major platforms that support Java.- Chapter 13

Filenames are problematic, even if you don’t have to worry about cross-platform idiosyncrasies. Users forget filenames, mistype them, can’t remember the exact path to files they need, and more. The proper way to ask a user to choose a file is to show them a list of the files and let them pick one. Most graphical user interfaces provide standard graphical widgets for selecting a file. In Java, the platform’s native file selector widget is exposed through the

java.awt.FileDialogclass. Like many native peer-based classes, however,FileDialogdoesn’t behave the same or provide the same services on all platforms. Therefore, the Java Foundation Classes™ 1.1 (Swing) provide a pure Java implementation of a file dialog, thejavax.swing.JFileChooserclass. Chapter 13 shows you how to use both these classes to provide a GUI file selection interface. In the final example, you’ll add a Swing-based GUI to the File Viewer program.- Chapter 14

We live on a planet where many languages are spoken, yet most programming languages still operate under the assumption that everything you need to say can be expressed in English. Java is starting to change that by adopting the multinational Unicode as its native character set. All Java chars and strings are given in Unicode. However, since there’s also a lot of non-Unicode legacy text in the world, in a dizzying array of encodings, Java also provides the classes you need to read and write this text in these encodings as well. Chapter 14 introduces you to the multitude of character sets used around the world, and develops a simple applet to test which ones your browser/VM combination supports.

- Chapter 15

A language that supports international text must separate the reading and writing of raw bytes from the reading and writing of characters, since in an international system they are no longer the same thing. Classes that read characters must be able to parse a variety of character encodings, not just ASCII, and translate them into the language’s native character set. Classes that write characters must be able to translate the language’s native character set into a variety of formats and write those. In Java, this task is performed by the

ReaderandWriterclasses. Chapter 15 shows you how to use these classes, and adds support for multilingual text to the File Viewer program.- Chapter 16

Java 1.0 did not provide classes for specifying the width, precision, and alignment of numeric strings. Java 1.1 and later make these available as subclasses of

java.text.NumberFormat. As well as handling the traditional formatting achieved by languages like C and Fortran,NumberFormatalso internationalizes numbers with different character sets, thousands separators, decimal points, and digit characters. Chapter 16 shows you how to use this class and its subclasses for traditional tasks, like lining up the decimal points in a table of prices, and nontraditional tasks, like formatting numbers in Egyptian Arabic.- Chapter 17

Chapter 17 introduces the Java Communications API, a standard extension available for Java 1.1 and later that allows Java applications and trusted applets to send and receive data to and from the serial and parallel ports of the host computer. The Java Communications API allows your programs to communicate with essentially any device connected to a serial or parallel port, like a printer, a scanner, a modem, a tape backup unit, and so on.

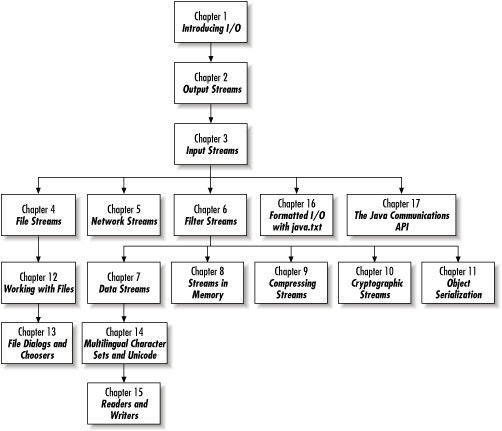

Chapter 1 through Chapter 3 provide the basic background you’ll need to do any sort of work with I/O in Java. After that, you should feel free to jump around as your interests take you. There are, however, some interdependencies between specific chapters. Figure 0.1 should allow you to map out possible paths through the book.

A few examples in later chapters depend on material from earlier

chapters—for instance, many examples use the

FileInputStream class discussed in Chapter 4—but they should not be difficult to

understand in the large.

Get Java I/O now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.