Chapter 1. Writing Servlets and JSPs

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to bring relative newcomers up to speed in writing, compiling, and packaging servlets and JSPs. If you have never developed a servlet or JSP before, or just need to brush up on the technology to jumpstart your development, then the upcoming recipes provide simple programming examples and an overview of the components that you require on the user classpath to compile servlets.

Recipe 1.1 and Recipe 1.2 provide a brief introduction to servlets and JSPs, respectively. A comprehensive description of a servlet or JSP’s role in the Java 2 Platform, Enterprise Edition (J2EE), is beyond the scope of these recipes. However, information that relates directly to J2EE technology, such as databases and JDBC; using servlets with the Java Naming and Directory Interface (JNDI); and using servlets with JavaMail (or email) is distributed throughout the book (and index!).

The “See Also” sections concluding each recipe provide pointers to closely related chapters, an online tutorial managed by Sun Microsystems, and other O’Reilly books that cover these topics in depth.

1.1. Writing a Servlet

Solution

Create

a Java class that extends

javax.servlet.http.HttpServlet.

Make sure to import the

classes from servlet.jar

(or servlet-api.jar)—you’ll

need them to compile the

servlet.

Discussion

A servlet is a Java class that is designed to respond with dynamic content to client requests over a network. If you are familiar with Common Gateway Interface (CGI) programs, then servlets are a Java technology that can replace CGI programs. Often called a web component (along with JSPs), a servlet is executed within a runtime environment provided by a servlet container or web container such as Jakarta Tomcat or BEA WebLogic.

Tip

A web container can be an add-on component to an HTTP server, or it can be a standalone server such as Tomcat, which is capable of managing HTTP requests for both static content (HTML files) as well as for servlets and JSPs.

Servlets are installed in web containers as part of web applications . These applications are collections of web resources such as HTML pages, images, multimedia content, servlets, JavaServer Pages, XML configuration files, Java support classes, and Java support libraries. When a web application is deployed in a web container, the container creates and loads instances of the Java servlet class into its Java Virtual Machine (JVM) to handle requests for the servlet.

Tip

A servlet handles each request as a separate thread. Therefore, servlet developers have to consider whether to synchronize access to instance variables, class variables, or shared resources such as a database connection, depending on how these resources are used.

All servlets implement the

javax.servlet.Servlet

interface.

Web application

developers typically

write servlets that

extend javax.servlet.http.HttpServlet,

an abstract class that

implements the Servlet

interface and is

specially designed to

handle HTTP requests.

The following basic sequence occurs when the web container creates a servlet instance:

The servlet container calls the servlet’s

init( )method, which is designed to initialize resources that the servlet might use, such as a logger (see Chapter 14). Theinit( )method gets called only once during the servlet’s lifetime.The

init( )method initializes an object that implements thejavax.servlet.ServletConfiginterface. This object gives the servlet access to initialization parameters declared in the deployment descriptor (see Recipe 1.5).ServletConfigalso gives the servlet access to ajavax.servlet.ServletContextobject, with which the servlet can log messages, dispatch requests to other web components, and get access to other web resources in the same application (see Recipe 13.5).

Tip

Servlet developers

are not

required

to

implement

the

init(

)

method in

their

HttpServlet

subclasses.

The servlet container calls the servlet’s

service( )method in response to servlet requests. In terms ofHttpServlets,service( )automatically calls the appropriate HTTP method to handle the request by calling (generally) the servlet’sdoGet( )ordoPost( )methods. For example, the servlet responds to a user sending aPOSTHTTP request with adoPost( )method execution.When calling the two principal

HttpServletmethods,doGet( )ordoPost( ), the servlet container createsjavax.servlet.http.HttpServletRequestandHttpServletResponseobjects and passes them in as parameters to these request handler methods.HttpServletRequestrepresents the request;HttpServletResponseencapsulates the servlet’s response to the request.

Tip

Example

1-1

shows the

typical

uses of

the

request

and

response

objects.

It is a

good idea

to read

the

servlet

API

documentation

(at

http://java.sun.com/j2ee/1.4/docs/api/javax/servlet/http/package-summary.html),

as many of

the method

names

(e.g.,

request.getContextPath(

))

are

self-explanatory.

The servlet or web container, not the developer, manages the servlet’s lifecycle, or how long an instance of the servlet exists in the JVM to handle requests. When the servlet container is set to remove the servlet from service, it calls the servlet’s

destroy( )method, in which the servlet can release any resources, such as a database connection.

Example

1-1

shows a typical servlet

idiom for handling an

HTML

form. The doGet(

) method

displays the form itself.

The doPost(

) method

handles the submitted

form data, since in

doGet(

), the HTML

form

tag specifies the

servlet’s own address as

the target for the form

data.

The

servlet (named FirstServlet)

specifies that the

declared class is part of

the com.jspservletcookbook

package. It is important

to create packages for

your servlets and utility

classes, and then to

store your classes in a

directory structure

beneath

WEB-INF

that matches these

package names.

The FirstServlet

class imports the

necessary classes for

compiling a basic

servlet, which are the

emphasized import

statements in Example

1-1.

The Java class extends

HttpServlet.

The only defined methods

are doGet(

)

,

which displays the

HTML

form in response to a

GET

HTTP request, and

doPost(

), which

handles the posted data.

package com.jspservletcookbook;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.io.PrintWriter;

import java.util.Enumeration;import javax.servlet.ServletException;

import javax.servlet.http.HttpServlet;

import javax.servlet.http.HttpServletRequest;

import javax.servlet.http.HttpServletResponse;

public class FirstServlet extends HttpServlet {

public void doGet(HttpServletRequest request,

HttpServletResponse response) throws ServletException,

java.io.IOException {

//set the MIME type of the response, "text/html"

response.setContentType("text/html");

//use a PrintWriter to send text data to the client who has requested the

//servlet

java.io.PrintWriter out = response.getWriter( );

//Begin assembling the HTML content

out.println("<html><head>");

out.println("<title>Help Page</title></head><body>");

out.println("<h2>Please submit your information</h2>");

//make sure method="post" so that the servlet service method

//calls doPost in the response to this form submit

out.println(

"<form method=\"post\" action =\"" + request.getContextPath( ) +

"/firstservlet\" >");

out.println("<table border=\"0\"><tr><td valign=\"top\">");

out.println("Your first name: </td> <td valign=\"top\">");

out.println("<input type=\"text\" name=\"firstname\" size=\"20\">");

out.println("</td></tr><tr><td valign=\"top\">");

out.println("Your last name: </td> <td valign=\"top\">");

out.println("<input type=\"text\" name=\"lastname\" size=\"20\">");

out.println("</td></tr><tr><td valign=\"top\">");

out.println("Your email: </td> <td valign=\"top\">");

out.println("<input type=\"text\" name=\"email\" size=\"20\">");

out.println("</td></tr><tr><td valign=\"top\">");

out.println("<input type=\"submit\" value=\"Submit Info\"></td></tr>");

out.println("</table></form>");

out.println("</body></html>");

}//doGet

public void doPost(HttpServletRequest request,

HttpServletResponse response) throws ServletException,

java.io.IOException {

//display the parameter names and values

Enumeration paramNames = request.getParameterNames( );

String parName;//this will hold the name of the parameter

boolean emptyEnum = false;

if (! paramNames.hasMoreElements( ))

emptyEnum = true;

//set the MIME type of the response, "text/html"

response.setContentType("text/html");

//use a PrintWriter to send text data to the client

java.io.PrintWriter out = response.getWriter( );

//Begin assembling the HTML content

out.println("<html><head>");

out.println("<title>Submitted Parameters</title></head><body>");

if (emptyEnum){

out.println(

"<h2>Sorry, the request does not contain any parameters</h2>");

} else {

out.println(

"<h2>Here are the submitted parameter values</h2>");

}

while(paramNames.hasMoreElements( )){

parName = (String) paramNames.nextElement( );

out.println(

"<strong>" + parName + "</strong> : " +

request.getParameter(parName));

out.println("<br />");

}//while

out.println("</body></html>");

}// doPost

}You might have noticed that

doGet(

) and doPost(

) each throw

ServletException

and IOException.

The servlet throws

IOException

because the response.getWriter(

)

(as well as PrintWriter.close(

))

method call can throw an

IOException.

The doPost(

) and doGet(

) methods can

throw a ServletException

to indicate that a

problem occurred when

handling the request. For

example, if the servlet

detected a security

violation or some other

request problem, then it

could include the

following code within

doGet(

) or doPost(

):

//detects a problem that prevents proper request handling...

throw new ServletException("The servlet cannot handle this request.");

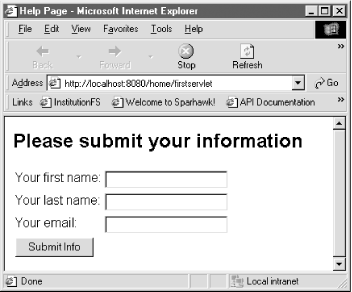

Figure

1-1

shows the output

displayed by the

servlet’s doGet(

)

method in a browser.

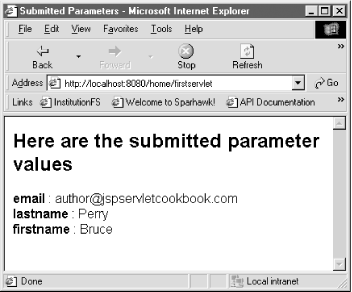

Figure

1-2

shows the servlet’s

output for the doPost(

) method.

See Also

Recipe

1.3

on compiling a servlet;

Recipe

1.4

on packaging servlets and

JSPs; Recipe

1.5

on creating the

deployment descriptor;

Chapter

2 on deploying

servlets and JSPs; Chapter

3 on naming

servlets; the javax.servlet.http

package JavaDoc:

http://java.sun.com/j2ee/1.4/docs/api/javax/servlet/http/package-summary.html;

the J2EE tutorial from

Sun Microsystems:

http://java.sun.com/j2ee/tutorial/1_3-fcs/doc/J2eeTutorialTOC.html;

Jason Hunter’s

Java

Servlet

Programming

(O’Reilly).

1.2. Writing a JSP

Solution

Create the JSP as a text file using HTML template text as needed. Store the JSP file at the top level of the web application.

Discussion

A JavaServer Pages (JSP) component is a type of Java servlet that is designed to fulfill the role of a user interface for a Java web application. Web developers write JSPs as text files that combine HTML or XHTML code, XML elements, and embedded JSP actions and commands. JSPs were originally designed around the model of embedded server-side scripting tools such as Microsoft Corporation’s ASP technology; however, JSPs have evolved to focus on XML elements, including custom-designed elements, or custom tags , as the principal method of generating dynamic web content.

JSP files typically have a .jsp extension, as in mypage.jsp. When a client requests the JSP page for the first time, or if the developer precompiles the JSP (see Chapter 5), the web container translates the textual document into a servlet.

Tip

The JSP 2.0 specification refers to the conversion of a JSP into a servlet as the translation phase . When the JSP (now a servlet class) responds to requests, the specification calls this stage the request phase . The resulting servlet instance is called the page implementation object .

A JSP compiler (such as Tomcat’s Jasper component) automatically converts the text-based document into a servlet. The web container creates an instance of the servlet and makes the servlet available to handle requests. These tasks are transparent to the developer, who never has to handle the translated servlet source code (although they can examine the code to find out what’s happening behind the scenes, which is always instructive).

The developer focuses on the JSP’s dynamic behavior and which JSP elements or custom-designed tags she uses to generate the response. Developing the JSP as a text-based document rather than Java source code allows a professional designer to work on the graphics, HTML, or dynamic HTML, leaving the XML tags and dynamic content to programmers.

Example

1-2

shows a JSP that displays

the current date

and time. The example JSP

shows how to import and

use a custom tag library,

which Chapter

23

describes in great

detail. The code also

uses the jsp:useBean

standard action, a

built-in XML element that

you can use to create a

new Java object for use

in the JSP page. Here are

the basic steps for

writing a JSP:

Open up a text editor, or a programmer’s editor that offers JSP syntax highlighting.

If you are developing a JSP for handling HTTP requests, then input the HTML code just as you would for an HTML file.

Include any necessary JSP directives, such as the

taglibdirective in Example 1-2, at the top of the file. A directive begins with the<%@s.Type in the standard actions or custom tags wherever they are needed.

Save the file with a .jsp extension in the directory you have designated for JSPs. A typical location is the top-level directory of a web application that you are developing in your filesystem.

Tip

Some JSPs are developed as XML files, or JSP documents, consisting solely of well-formed XML elements and their attributes. The JSP 2.0 specification recommends that you give these files a .jspx extension. See Recipe 5.5 for further details on JSP documents.

<%-- use the 'taglib' directive to make the JSTL 1.0 core tags available; use the uri

"http://java.sun.com/jsp/jstl/core" for JSTL 1.1 --%>

<%@ taglib uri="http://java.sun.com/jstl/core" prefix="c" %>

<%-- use the 'jsp:useBean' standard action to create the Date object; the object is set

as an attribute in page scope

--%>

<jsp:useBean id="date" class="java.util.Date" />

<html>

<head><title>First JSP</title></head>

<body>

<h2>Here is today's date</h2>

<c:out value="${date}" />

</body>

</html>To view the output of this file in a browser, request the file by typing the URL into the browser location field, as in: http://localhost:8080/home/firstJ.jsp. The name of the file is firstJ.jsp. If this is the first time that anyone has requested the JSP, then you will notice a delay as the JSP container converts your text file into Java source code, then compiles the source into a servlet.

Tip

You can avoid

delays by

precompiling

the JSP.

If you

request

the JSP

with a

jsp_precompile=true

parameter,

Tomcat

converts

the JSP,

but does

not send

back a

response.

An example

is

http://localhost:8080/home/firstJ.jsp?jsp_precompile=true.

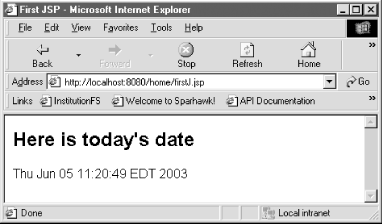

Figure 1-3 shows the JSP output in a browser.

If you select “View

Source” from the browser

menu to view the page’s

source code, you won’t

see any of the special

JSP syntax: the comment

characters (<%--

--%>

),

the taglib

directive, the jsp:useBean

action, or the c:out

tag. The servlet sends

only the template text

and the generated date

string to the

client.

See Also

Recipe 5.1-Recipe 5.3 on precompiling JSPs; Chapter 2 on deploying servlets and JSPs; Recipe 1.1 and Recipe 1.3 on writing and compiling a servlet; Recipe 1.4 on packaging servlets and JSPs; Recipe 1.5 on creating the deployment descriptor; the J2EE tutorial from Sun Microsystems: http://java.sun.com/j2ee/tutorial/1_3-fcs/doc/J2eeTutorialTOC.html; Hans Bergsten’s JavaServer Pages (O’Reilly).

1.3. Compiling a Servlet

Solution

Make

sure that servlet.jar

(for Tomcat 4.1.24) or

servlet-api.jar

(for Tomcat 5) is on your

user classpath. Use

javac

as you would for any

other Java source

file.

Discussion

At a minimum, you have to place the servlet classes on your classpath in order to compile a servlet. These classes are located in these Java packages:

javax.servletjavax.servlet.http

Tomcat 5 supports the servlet API 2.4; the JAR file that you need on the classpath is located at <Tomcat-5-installation-directory>/common/lib/servlet-api.jar. Tomcat 4.1.24 uses the servlet 2.3 API. The servlet classes are located at: <Tomcat-4-installation-directory>/common/lib/servlet.jar.

For BEA

WebLogic 7.0, the servlet

classes and many other

subpackages of the

javax

package (e.g., javax.ejb,

javax.mail,

javax.sql)

are located at: <WebLogic-installation-directory>/weblogic700/server/lib/weblogic.jar.

Tip

If you are using Ant to compile servlet classes, then proceed to Recipe 4.4, do not pass Go, do not collect $200. That recipe is devoted specifically to the topic of using Ant to compile a servlet. If you use an IDE, follow its instructions for placing a JAR file on the classpath.

The following command line compiles a servlet in the src directory and places the compiled class, nested within its package-related directories, in the build directory:

javac -classpath K:\tomcat5\jakarta-tomcat-5\dist\common\lib\servlet-api.jar

-d ./build ./src/FirstServlet.javaFor this command line to run successfully, you must change to the parent directory of the src directory.

Tip

Recipe 1.4 explains the typical directory structure, including the src directory, for developing a web application.

If the servlet depends on any other libraries, you have to include those JAR files on your classpath as well. I have included only the servlet-api.jar JAR file in this command line.

You also have to substitute the directory path for your own installation of Tomcat for this line of the prior command-line sequence:

K:\tomcat5\jakarta-tomcat-5\dist\common\lib\servlet-api.jar

This

command line uses the

built-in javac

compiler that comes with

the

Sun

Microsystems Java

Software Development Kit

(JDK). For this command

to work properly, you

have to include the

location of the Java SDK

that you are using in the

PATH

environment variable. For

example, on a Unix-based

Mac OS X 10.2 system, the

directory path /usr/bin

must be included in the

PATH

variable. On my

Windows

NT machine, the PATH

includes h:\j2sdk1.4.1_01\bin.

See Also

Chapter 2 on deploying servlets and JSPs; Chapter 3 on naming servlets; Recipe 1.4 on packaging servlets and JSPs; Recipe 1.5 on creating the deployment descriptor; the J2EE tutorial from Sun Microsystems: http://java.sun.com/j2ee/tutorial/1_3-fcs/doc/J2eeTutorialTOC.html; Jason Hunter’s Java Servlet Programming (O’Reilly).

1.4. Packaging Servlets and JSPs

Problem

You want to set up a directory structure for packaging and creating a Web ARchive (WAR) file for servlets and JSPs.

Solution

Set up a directory structure in

your filesystem, then use

the jar

tool or Ant to create the

WAR.

Discussion

Except in the rarest of circumstances, you’ll usually develop a servlet or JSP as part of a web application. It is relatively easy to set up a directory structure on your filesystem to hold web-application components, which include HTML files, servlets, JSPs, graphics, JAR libraries, possibly movies and sound files, as well as XML configuration files (such as the deployment descriptor; see Recipe 1.5).

The simplest organization for this

structure is to create

the exact layout of a web

application on your

filesystem, then use the

jar

tool to create a WAR

file.

Tip

A WAR file is like a ZIP archive. You deploy your web application into a web container by deploying the WAR. See Chapter 2 for recipes about various deployment scenarios.

The web application structure involving the WEB-INF subdirectory is standard to all Java web applications and specified by the servlet API specification (in the section named Web Applications. Here is what this directory structure looks like, given a top-level directory name of myapp:

/myapp

/images

/WEB-INF

/classes

/libThe servlet specification

specifies a WEB-INF

subdirectory and two

child directories,

classes

and lib.

The WEB-INF

subdirectory contains the

application’s deployment

descriptor, named

web.xml.

The JSP files and HTML

live in the top-level

directory

(myapp).

Servlet classes, JavaBean

classes, and any other

utility classes are

located in the WEB-INF/classes

directory, in a structure

that matches their

package

name. If you have a

fully

qualified class name of

com.myorg.MyServlet,

then this servlet class

must be located in

WEB-INF/classes/com/myorg/MyServlet.class.

The WEB-INF/lib directory contains any JAR libraries that your web application requires, such as database drivers, the log4j.jar, and the required JARs for using the JavaServer Pages Standard Tag Library (see Chapter 23).

Once you are ready to test the application in WAR format, change to the top-level directory. Type the following command, naming the WAR file after the top-level directory of your application. These command-line phrases work on both Windows and Unix systems (I used them with Windows NT 4 and Mac OS X 10.2):

jar cvf myapp.war .

Don’t forget the final dot

(.) character, which

specifies to the jar

tool to include the

current directory’s

contents and its

subdirectories in the WAR

file. This command

creates the myapp.war

file in the current

directory.

Tip

The WAR name becomes the application name and context path for your web application. For example, myapp.war is typically associated with a context path of /myapp when you deploy the application to a web container.

If you want to view the contents of the WAR at the command line, type this:

jar tvf alpine-final.war

If the WAR file is very large and you want to view its contents one page at a time, use this command:

jar tvf alpine-final.war |more

Here is example output from this command:

H:\classes\webservices\finalproj\dist>jar tvf alpine-final.war

0 Mon Nov 18 14:10:36 EST 2002 META-INF/

48 Mon Nov 18 14:10:36 EST 2002 META-INF/MANIFEST.MF

555 Tue Nov 05 17:08:16 EST 2002 request.jsp

914 Mon Nov 18 08:53:00 EST 2002 response.jsp

0 Mon Nov 18 14:10:36 EST 2002 WEB-INF/

0 Mon Nov 18 14:10:36 EST 2002 WEB-INF/classes/

0 Tue Nov 05 11:09:34 EST 2002 WEB-INF/classes/com/

0 Tue Nov 05 11:09:34 EST 2002 WEB-INF/classes/com/parkerriver/

CONTINUED...Many development teams are using Ant to compile and create WAR files for their servlets and JSPs. Recipe 2.6 describes using Ant for developing and updating web applications.

I jumpstart your progress toward that recipe by showing the kind of directory structure you might use for a comprehensive web application, one that contains numerous servlets, JSPs, static HTML files, as well as various graphics and multimedia components. When using Ant to build a WAR file from this kind of directory structure, you can filter out the directories that you do not want to include in the final WAR, such as the top-level src, dist, and meta directories.

myapp

/build

/dist

/lib

/meta

/src

/web

/images

/multimedia

/WEB-INF

/classes

/lib

/tlds

/jspfSee Also

Chapter 2 on deploying servlets and JSPs; Chapter 3 on naming servlets; The deployment sections of Tomcat: The Definitive Guide, by Brittain and Darwin (O’Reilly); the J2EE tutorial from Sun Microsystems: http://java.sun.com/j2ee/tutorial/1_3-fcs/doc/J2eeTutorialTOC.html.

1.5. Creating the Deployment Descriptor

Solution

Name the XML file web.xml and place it in the WEB-INF directory of your web application. If you do not have an existing example of web.xml, then cut and paste the examples given in the servlet v2.3 or 2.4 specifications and start from there.

Discussion

The deployment descriptor is a very important part of your web application. It conveys the requirements for your web application in a concise format that is readable by most XML editors. The web.xml file is where you:

Register and create URL mappings for your servlets

Register or specify any of the application’s filters and listeners

Specify context init parameter name/value pairs

Configure error pages

Specify your application’s welcome files

Configure session timeouts

Specifiy security settings that control who can request which web components

This is just a subset of the configurations that you can use with web.xml. While a number of chapters in this book contain detailed examples of web.xml (refer to the “See Also” section), this recipe shows simplified versions of the servlet v2.3 and v2.4 deployment descriptors.

Example

1-3

shows a

simple web application

with a servlet,

a filter,

a listener,

and a session-config

element, as well as an

error-page

configuration. The

web.xml

in Example

1-3

uses the servlet v2.3

Document

Type Definition (DTD).

The main difference

between the deployment

descriptors of 2.3 and

2.4 is that 2.3 uses a

DTD and 2.4 is based on

an XML

schema. You’ll notice

that the old version of

web.xml

has the DOCTYPE

declaration at the top of

the file, while the

2.4

version uses the

namespace attributes of

the web-app

element to refer to the

XML schema. The XML

elements of Example

1-3

have to be in the same

order as specified by the

DTD.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="ISO-8859-1"?><!DOCTYPE web-app PUBLIC "-//Sun Microsystems, Inc.//DTD Web Application 2.3//EN" "http://java.sun.com/dtd/web-application_2_3.dtd" > <web-app> <display-name>Servlet 2.3 deployment descriptor</display-name> <filter> <filter-name>RequestFilter</filter-name> <filter-class>com.jspservletcookbook.RequestFilter</filter-class> </filter> <filter-mapping> <filter-name>RequestFilter</filter-name> <url-pattern>/*</url-pattern> </filter-mapping> <listener> <listener-class>com.jspservletcookbook.ReqListener</listener-class> </listener> <servlet> <servlet-name>MyServlet</servlet-name> <servlet-class>com.jspservletcookbook.MyServlet</servlet-class> </servlet> <servlet-mapping> <servlet-name> MyServlet </servlet-name> <url-pattern>/myservlet</url-pattern> </servlet-mapping> <session-config> <session-timeout>15</session-timeout> </session-config> <error-page> <error-code>404</error-code> <location>/err404.jsp</location> </error-page> </web-app>

Example

1-3

shows the web.xml

file for an application

that has just one

servlet, accessed at the

path

<context

path>/myservlet.

Sessions

time out in 15 minutes

with this application. If

a client requests a URL

that cannot be found, the

web container forwards

the request to the

/err404.jsp

page, based on the

error-page

configuration. The

filter

named RequestFilter

applies to all requests

for static and dynamic

content in this context.

At startup, the web

container creates an

instance of the

listener

class com.jspservletcookbook.ReqListener.

Everything

about Example

1-4

is the same as Example

1-3,

except that the web-app

element at the top of the

file refers to an XML

schema with its namespace

attributes. In addition,

elements can appear in

arbitrary order with the

servlet v2.4 deployment

descriptor. For instance,

if you were so inclined

you could list your

servlets and mappings

before your listeners and

filters.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="ISO-8859-1"?><web-app xmlns="http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/j2ee"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation=

"http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/j2ee

http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/j2ee/web-app_2_4.xsd" version="2.4">

<!-- the rest of the file is the same as Example 1-3 after the web-app opening tag -->

</web-app>Tip

The servlet 2.4

version of

the

deployment

descriptor

also

contains

definitions

for

various

elements

that are

not

included

in the

servlet

2.3

web.xml

version:

jsp-config,

message-destination,

message-destination-ref,

and

service-ref.

The syntax

for these

elements

appears in

the

specifications

for JSP

v2.0 and

J2EE

v1.4.

See Also

Chapter 2 on deploying servlets and JSPs; Chapter 3 on naming servlets; Chapter 9 on configuring the deployment descriptor for error handling; the J2EE tutorial from Sun Microsystems: http://java.sun.com/j2ee/tutorial/1_3-fcs/doc/J2eeTutorialTOC.html.

Get Java Servlet & JSP Cookbook now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.