Welcome to Swing! By now, you’re probably wondering what Swing is, and how you can use it to spice up your Java applications. Or perhaps you’re curious as to how the Swing components fit into the overall Java strategy. Then again, maybe you just want to see what all the hype is about. Well, you’ve come to the right place; this book is all about Swing and its components. So let’s dive right in and answer the first question that you’re probably asking right now, which is...

If you poke around the Java home page (http://java.sun.com/ ), you’ll find Swing advertised as a set of customizable graphical components whose look-and-feel can be dictated at runtime. In reality, however, Swing is much more than this. Swing is the next-generation GUI toolkit that Sun Microsystems is developing to enable enterprise development in Java. By enterprise development, we mean that programmers can use Swing to create large-scale Java applications with a wide array of powerful components. In addition, you can easily extend or modify these components to control their appearance and behavior.

Swing is not an acronym. The name represents the collaborative choice of its designers when the project was kicked off in late 1996. Swing is actually part of a larger family of Java products known as the Java Foundation Classes ( JFC), which incorporate many of the features of Netscape’s Internet Foundation Classes (IFC), as well as design aspects from IBM’s Taligent division and Lighthouse Design. Swing has been in active development since the beta period of the Java Development Kit (JDK)1.1, circa spring of 1997. The Swing APIs entered beta in the latter half of 1997 and their initial release was in March of 1998. When released, the Swing 1.0 libraries contained nearly 250 classes and 80 interfaces.

Although Swing was developed separately from the core Java Development Kit, it does require at least JDK 1.1.5 to run. Swing builds on the event model introduced in the 1.1 series of JDKs; you cannot use the Swing libraries with the older JDK 1.0.2. In addition, you must have a Java 1.1-enabled browser to support Swing applets.

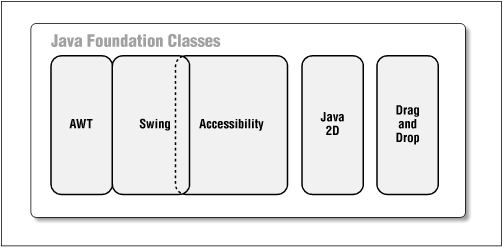

The Java Foundation Classes (JFC) are a suite of libraries designed to assist programmers in creating enterprise applications with Java. The Swing API is only one of five libraries that make up the JFC. The Java Foundation Classes also consist of the Abstract Window Toolkit (AWT), the Accessibility API, the 2D API, and enhanced support for drag-and-drop capabilities. While the Swing API is the primary focus of this book, here is a brief introduction to the other elements in the JFC:

- AWT

The Abstract Window Toolkit is the basic GUI toolkit shipped with all versions of the Java Development Kit. While Swing does not reuse any of the older AWT components, it does build off of the lightweight component facilities introduced in AWT 1.1.

- Accessibility

The accessibility package provides assistance to users who have trouble with traditional user interfaces. Accessibility tools can be used in conjunction with devices such as audible text readers or braille keyboards to allow direct access to the Swing components. Accessibility is split into two parts: the Accessibility API, which is shipped with the Swing distribution, and the Accessibility Utilities API, distributed separately. All Swing components contain support for accessibility, so this book dedicates an entire chapter (Chapter 24) to accessibility design and use.

- 2D API

The 2D API contains classes for implementing various painting styles, complex shapes, fonts, and colors. This Java package is loosely based on APIs that were licensed from IBM’s Taligent division. The 2D API classes are not part of Swing, so they will not be covered in this book.

- Drag and Drop

Drag and drop is one of the more common metaphors used in graphical interfaces today. The user is allowed to click and “hold” a GUI object, moving it to another window or frame in the desktop with predictable results. The Drag and Drop API allows users to implement droppable elements that transfer information between Java applications and native applications. Drag and Drop is also not part of Swing, so we will not discuss it here.

Figure 1.1 enumerates the various components of the Java Foundation Classes. Because part of the Accessibility API is shipped with the Swing distribution, we show it overlapping Swing.

No. Swing is actually built on top of the core 1.1 and 1.2 AWT libraries. Because Swing does not contain any platform-specific (native) code, you can deploy the Swing distribution on any platform that implements the Java 1.1.5 virtual machine or above. In fact, if you have JDK 1.2 on your platform, then the Swing classes will already be available and there’s nothing further to download. If you do not have JDK 1.2, you can download the entire set of Swing libraries as a set of Java Archive (JAR) files from the Swing home page: http://java.sun.com/products/jfc . In either case, it is generally a good idea to visit this URL for any extra packages or look-and-feels that may be distributed separately from the core Swing libraries.

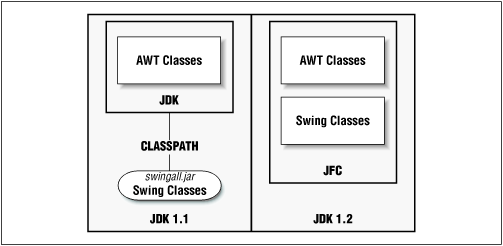

Figure 1.2 shows the relationship between Swing,

AWT, and the Java Development Kit in both the 1.1 and 1.2 JDKs. In

JDK 1.1, the Swing classes must be downloaded separately and included

as an archive file on the classpath

(swingall.jar).[2] JDK 1.2 comes with

a Swing distribution, although the relationship between Swing and the

rest of the JDK has shifted during the beta process. Nevertheless, if

you have installed JDK 1.2, you should have Swing.

Swing contains nearly twice the number of graphical components as its

immediate predecessor, AWT 1.1. Many are components that have been

scribbled on programmer wish-lists since Java first

debuted—including tables, trees, internal frames, and a

plethora of advanced text components. In addition, Swing contains

many design advances over AWT. For example, Swing introduces a new

Action

class that makes it easier to

coordinate GUI components with the functionality they perform.

You’ll also find that a much cleaner design prevails throughout

Swing; this cuts down on the number of unexpected surprises that

you’re likely to face while coding.

Swing depends extensively on the event handling mechanism of AWT 1.1, although it does not define a comparatively large amount of events for itself. Each Swing component also contains a variable number of exportable properties. This combination of properties and events in the design was no accident. Each of the Swing components, like the AWT 1.1 components before them, adhere to the popular JavaBeans specification. As you might have guessed, this means that you can import all of the Swing components into various GUI-builder tools—useful for powerful visual programming.[3]

To understand why Swing exists, it helps to understand the market forces that drive Java as a whole. The Java Programming Language was developed in 1993 and 1994, largely under the guidance of James Gosling and Bill Joy at Sun Microsystems, Inc. When Sun released the Java Development Kit on the Internet, it ignited a firestorm of excitement that swept through the computing industry. At first, developers primarily experimented with Java for applets : mini-programs that were embedded in client-side web browsers. However, as Java matured over the course of the next two years, many developers began using Java to develop full-scale applications.

Or at least they tried. As developers ported Java to more and more platforms, its weak points started to show. The language was robust and scalable, extremely powerful as a networking tool, and served well as an easy-to-learn successor to the more established C++. The primary criticism, however, was that it was an interpreted language, which means that by definition it executed code slower than its native, compiled equivalents. Consequently, many developers flocked to just-in-time (JIT) compilers—highly optimized interpreters—to speed up their large-scale applications. This solved many problems. Throughout it all, however, one weak point that continually received scathing criticism was the graphical widgets that Java was built on: the Abstract Window Toolkit (AWT). The primary issue here was that AWT provided only the minimal amount of functionality necessary to create a windowing application. For enterprise applications, it quickly became clear that programmers needed something bigger.

After nearly a year of intense scrutiny, the AWT classes were ready for a change. From Java 1.0 to Java 1.1, the AWT reimplemented its event model from a “chain” design to an “event subscriber” design. This meant that instead of propagating events up a predefined hierarchy of components, interested classes simply registered with other components to receive noteworthy events. Because events typically involve only the sender and receiver, this eliminated much of the overhead in propagating them. When component events were triggered, an event object was passed only to those classes interested in receiving them.

JavaSoft developers also began to see that relying on native widgets for the AWT components was proving to be troublesome. Similar components looked and behaved differently on many platforms, and coding for the ever-expanding differences of each platform became a maintenance nightmare. In addition, reusing the component widgets for each platform limited the abilities of the components and proved expensive on system memory.

Clearly, JavaSoft knew that AWT wasn’t enough. It wasn’t

that the AWT classes didn’t work; they simply didn’t

provide the functionality necessary for full scale enterprise

applications. At the 1997 JavaOne Conference in San Francisco,

JavaSoft announced the Java Foundation Classes. Key to the design of

the JFC was that the new Swing components would be written entirely

in Java and have a consistent look-and-feel across platforms. This

allowed Swing and the JFC to be used on any platform that supported

Java 1.1 or later; all the user had to do was to include the

appropriate JAR files on the CLASSPATH, and each

of the components were available for use.

At about the same time that Sun Microsystems, Inc. announced the JFC, their chief competitor, Microsoft, announced a similar framework under the name Application Foundation Classes (AFC). The AFC libraries consist of two major packages: UI and FX.

The AFC classes are similar to JFC in many respects, and although the event mechanisms are different, the goals are the same. The most visible difference to programmers is in the operating environment: JFC requires the services of JDK 1.1, while the AFC can co-exist with the more browser-friendly JDK 1.0.2. In addition, AFC does not reuse any of the AWT 1.1 classes, but instead defines its own lightweight hierarchy of graphics components.

Which development library is better? Of course, Microsoft would have you believe that AFC far exceeds JFC, while Sun would have you believe the opposite. Putting aside the marketing hype and any religious issues, the choice largely depends on personal preference. Both JFC and AFC contain enough classes to build a very robust enterprise application, and each side has its own pros and cons.

[2] The standalone

Swing distributions contain several other JAR files.

swingall.jar is everything (except the contents

of multi.jar) wrapped into one lump, and is all

you normally need to know about. For completeness, the other JAR

files are: swing.jar, which contains everthing

but the individual look-and-feel packages;

motif.jar, which contains the Motif (Unix)

look-and-feel; windows.jar, which contains the

Windows look-and-feel; multi.jar, which contains

a special look-and-feel that allows additional (often non-visual)

L&Fs to be used in conjunction with the primary L&F; and

beaninfo.jar, which contains special classes

used by GUI development tools.

[3] Currently, most of the IDEs are struggling to fully support Swing. However, we expect this to improve rapidly over time.

Get Java Swing now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.