Now comes the fun part: turning these XML documents into Java object instances. I’m going to really take this process step by step, even though the steps are awfully simple. The point of this exercise isn’t to bore you or fill pages; you need to be able to understand exactly what happens so you can track down problems. As a general rule, the higher level the API, the more that happens without your direct intervention. That means that more can go wrong without the casual user being able to do a thing about it. Since you’re not a casual user (at least not after working through this book), you’ll want to be able to dig in and figure out what’s going on.

The first step in unmarshalling

is getting

access to your XML input.

I’ve already spent a bit of time detailing the

process of creating that XML; now you need to get a handle to it

through a Java input method. The easiest way to do this is to wrap

the XML data in either an InputStream or a

Reader, both from the java.io

package. When using JAXB, you’ll need to limit your

input format to InputStreams, as

Readers aren’t supported

(although many other frameworks do support

Readers, it is simple enough to convert between

the two input formats).

If you know much about Java, there isn’t any special

method you need to invoke to open a stream; however, you do need to

understand what state the stream is in when returned to you after

unmarshalling completes. Specifically, you should be aware of whether

the stream you supplied to the unmarshalling process is open or

closed when returned from the unmarshal( ) method.

The answer with respect to the JAXB framework is that the stream is

closed. That effectively ends the use of the stream once

unmarshalling occurs. Trying to

use the stream after

unmarshalling results in an exception like this:

java.io.IOException: Stream closed

at java.io.BufferedInputStream.ensureOpen(BufferedInputStream.java:123)

at java.io.BufferedInputStream.reset(BufferedInputStream.java:371)

at javajaxb.RereadStreamTest.main(RereadStreamTest.java:84)As a result, you don’t expect to continue using the stream, even through buffering or other I/O tricks. That will save you the hassle of writing lots of I/O code, compiling, and then getting errors at runtime and having to rewrite large chunks of your code. If you do need to get access to input data once it has been unmarshalled, you will need to create a new stream for the data and read from that new stream:[9]

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

File xmlFile = new File(args[0]);

FileInputStream inputStream = new FileInputStream(xmlFile);

// Buffer input

BufferedInputStream bufferedStream =

new BufferedInputStream(inputStream);

bufferedStream.mark(bufferedStream.available( ));

// Unmarshal

Movies movies = Movies.unmarshal(bufferedStream);

FileInputStream newInputStream = new FileInputStream(xmlFile);

// Read the stream and output (for testing)

BufferedReader reader = new BufferedReader(

new InputStreamReader(newInputStream));

String line = null;

while ((line = reader.readLine( )) != null) {

System.out.println(line);

}

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace( );

}

}Other than these somewhat rare issues, if you can write a simple

InputStream construction statement,

you’re ready to turn your XML input into Java

output. Be sure to remember that you can use a file, network

connection, URL, or any other source for input, and

you’re all set.

You should still have the generated

source files from the movies

database (or your own DTD) from the last chapter. Open the top-level

object—the one that corresponds to your root element. If you

used the movies DTD, this object is Movies.java. Search through the file for the

unmarshal( ) methods, which will convert your XML

to Java. Here are the signatures for these methods in the

Movies object:

public static Movies unmarshal(XMLScanner xs, Dispatcher d)

throws UnmarshalException;

public static Movies unmarshal(XMLScanner xs)

throws UnmarshalException;

public static Movies unmarshal(InputStream in)

throws UnmarshalException;

public void unmarshal(Unmarshaller u)

throws UnmarshalException;Of these four, there’s really only one that I care

much about—the third one, which I’ve boldfaced

and takes an InputStream as an argument. The

reason why the others are less important to common programming is

that they involve using specific JAXB constructs; it builds a

dependency on JAXB into your application—possibly a specific

version of JAXB, which I try to avoid as a general principle. This

isn’t because JAXB isn’t a good

framework; I recommend it for any data binding framework, especially

when you have the option to use a common input parameter like an

InputStream (as discussed in the last section).

The returned object on this method, as well as the other three, is an

instance of the Movies class. This

shouldn’t be surprising, as you want the data in the

supplied input stream to be converted into Java object instances, and

this is the topmost object of interest. You can then use this object

like any other:

System.out.println("*** Movie Database ***");

List movies = movies.getMovie( );

for (Iterator i = movies.iterator(); i.hasNext( ); ) {

Movie movie = (Movie)i.next( );

System.out.println(" * " + movie.getTitle( ));

}Here, you’d get a list like this:

*** Movie Database *** * Pitch Black * Memento

I’ll leave the rest of the discussion of result object use for the next main section, where it can be covered more thoroughly.

Finally, notice that the unmarshal( ) methods are

all static. This makes sense, as there is no object instance to

operate upon until after the method is invoked.

Here’s how you would turn an XML document into a

Java object:

try {

// Get XML input

File xmlFile = new File("movies.xml");

FileInputStream inputStream = new FileInputStream(xmlFile);

// Convert to Java

Movies movies = Movies.unmarshal(inputStream);

} catch (Exception e) {

// Handle errors

}I know that probably seems a bit simple after all this talk and detail, but that’s really it. What is interesting is how the objects are used and where the XML data comes from. I’ll take a slight detour into JAXB’s inner workings and then address that very topic (JAXB usage) next.

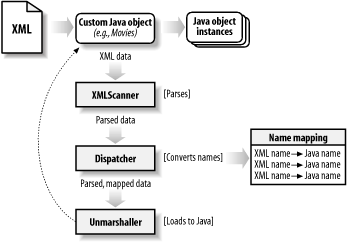

I want to talk briefly

about the

“in-between” of the JAXB

unmarshalling process—in other words, what happens between XML

input and Java output. The key classes involved in unraveling this

process in JAXB are javax.xml.bind.Unmarshaller,

javax.xml.marshal.XMLScanner, and

javax.xml.bind.Dispatcher. The

Unmarshaller class is the

centerpiece of the framework and relies

heavily on the XMLScanner mechanism for parsing.

The Dispatcher class takes

care of mapping XML structures to Java

ones. Here’s the basic rundown:

First, the JAXB framework

presupposes that a full XML parser is not

required. The assumption is that because all the XML data is derived

from a set of constraints, basic well-formedness rules (like start

tags matching end tags) and validity are assured before parsing

begins. This hearkens back to my earlier admonition to validate your

XML content before using it in a data binding context. Because of

these assumptions, an XMLScanner instance can

operate much like a SAX parser. However,

it ignores some basic error checking, as well as XML structures like

comments, which are not needed in data-bound classes. Of course, the

whole point of this class is to improve the performance issues

surrounding parsing data specifically for use in data-bound classes.

Second, JAXB uses a Dispatcher to handle name

conversion.

For every Dispatcher instance, there exists a map

of XML names and a map of Java class names. The XML names have

mappings from XML element names to Java class names (attributes and

so forth are not relevant here). The Java class names map from Java

classes to user-defined subclasses, in the case that users define

their own classes to unmarshal and marshal data into. This class,

then, provides several lookup methods, allowing the unmarshalling or

marshalling processes to supply an XML element name and get a Java

class name (or to supply a Java class name and get a user-defined

subclass name).

Finally, the unmarshalling process, through an

Unmarshaller instance, is accomplished by invoking

an unmarshal( ) method

on a

Dispatcher instance. The current

XMLScanner instance is examined, the current data

being parsed is converted to Java (looking up the appropriate name

using the Dispatcher instance), and the result is

one or more Java object instances. Then the scanner continues through

the XML input stream and the process repeats. Over and over, XML data

is turned into Java data, until the end of the XML input stream is

reached. Finally, the root-level object is returned to the invoking

program and you get to operate on this object. This is the tale of a

JAXB unmarshaller. This process is illustrated more completely in

Figure 4-4.

While it’s not mandatory that you understand this process, or even know about it, it can help you understand where performance problems creep in (and turn into a bona fide JAXB guru).

[9] This fragment is available as a complete Java source file from the web site, as ch04/src/java/javajaxb/RereadStreamTest.java.

Get Java & XML Data Binding now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.