The Web was a pretty boring place in its early days. Web pages were constructed from plain old HTML, so they could display information, and that was about all. Folks would click a link and then wait for a new web page to load. That was about as interactive as it got.

These days, most websites are almost as responsive as the programs on a desktop computer, reacting immediately to every mouse click. And it’s all thanks to the subjects of this book—JavaScript and its sidekick, jQuery.

JavaScript is a programming language that lets you supercharge your HTML with animation, interactivity, and dynamic visual effects.

JavaScript can make web pages more useful by supplying immediate feedback. For example, a JavaScript-powered shopping cart page can instantly display a total cost, with tax and shipping, the moment a visitor selects a product to buy. JavaScript can produce an error message immediately after someone attempts to submit a web form that’s missing necessary information.

JavaScript also lets you create fun, dynamic, and interactive interfaces. For example, with JavaScript, you can transform a static page of thumbnail images into an animated slideshow. Or you can do something more subtle like stuff more information on a page without making it seem crowded by organizing content into bite-size panels that visitors can access with a simple click of the mouse (Adding Tabbed Panels). Or add something useful and attractive, like pop-up tooltips that provide supplemental information for items on your web page (Providing Information with Tooltips).

Another one of JavaScript’s main selling points is its immediacy. It lets web pages respond instantly to actions like clicking a link, filling out a form, or merely moving the mouse around the screen. JavaScript doesn’t suffer from the frustrating delay associated with server-side programming languages like PHP, which rely on communication between the web browser and the web server. Because it doesn’t rely on constantly loading and reloading web pages, JavaScript lets you create web pages that feel and act more like desktop programs than web pages.

If you’ve visited Google Maps (http://maps.google.com), you’ve seen JavaScript in action. Google Maps lets you view a map of your town (or pretty much anywhere else for that matter), zoom in to get a detailed view of streets and bus stops, or zoom out to get a bird’s-eye view of how to get across town, the state, or the nation. While there were plenty of map sites before Google, they always required reloading multiple web pages (usually a slow process) to get to the information you wanted. Google Maps, on the other hand, works without page refreshes—it responds immediately to your choices.

The programs you create with JavaScript can range from the really simple (like popping up a new browser window with a web page in it) to full-blown web applications like Google Docs (http://docs.google.com), which lets you create presentations, edit documents, and build spreadsheets using your web browser with the feel of a program running directly on your computer.

Invented in 10 days by Brendan Eich at Netscape back in 1995, JavaScript is nearly as old as the Web itself. While JavaScript is well respected today, it has a somewhat checkered past. It used to be considered a hobbyist’s programming language, used for adding less-than-useful effects such as messages that scroll across the bottom of a web browser’s status bar like a stock ticker, or animated butterflies following mouse movements around the page. In the early days of JavaScript, it was easy to find thousands of free JavaScript programs (also called scripts) online, but many of those scripts didn’t work in all web browsers, and at times even crashed browsers.

Note

JavaScript has little to do with the Java programming language. JavaScript was originally named LiveScript, but a quick deal by marketers at Netscape eager to cash in on the success of Sun Microsystem’s then-hot programming language led to this long-term confusion. Don’t make the mistake of confusing the two…especially at a job interview!

In the early days, JavaScript also suffered from incompatibilities between the two prominent browsers, Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer. Because Netscape and Microsoft tried to outdo each other’s browsers by adding newer and (ostensibly) better features, the two browsers often acted in very different ways, making it difficult to create JavaScript programs that worked well in both.

Note

After Netscape introduced JavaScript, Microsoft introduced jScript, their own version of JavaScript included with Internet Explorer.

Fortunately, the worst of those days is nearly gone and contemporary browsers like Firefox, Safari, Chrome, Opera, and Internet Explorer 11 have standardized much of the way they handle JavaScript, making it easier to write JavaScript programs that work for most everyone. (There are still a few incompatibilities among current web browsers, so you’ll need to learn a few tricks for dealing with cross-browser problems. You’ll learn how to overcome browser incompatibilities in this book.)

In the past several years, JavaScript has undergone a rebirth, fueled by high-profile websites like Google, Yahoo!, and Flickr, which use JavaScript extensively to create interactive web applications. There’s never been a better time to learn JavaScript. With the wealth of knowledge and the quality of scripts being written, you can add sophisticated interaction to your website—even if you’re a beginner.

Note

JavaScript is also known by the name ECMAScript. ECMAScript is the “official” JavaScript specification, which is developed and maintained by an international standards organization called Ecma International: www.ecmascript.org.

JavaScript isn’t just for web pages, either. It’s proven to be such a useful programming language that if you learn JavaScript you can create Yahoo! Widgets and Google Apps, write programs for the iPhone, and tap into the scriptable features of many Adobe programs like Acrobat, Photoshop, Illustrator, and Dreamweaver. In fact, Dreamweaver has always offered clever JavaScript programmers a way to add their own commands to the program.

In the Yosemite version of the Mac OS X operating system, Apple lets users automate their Macs using JavaScript. In addition, JavaScript is used in many helpful front end web development tools like Gulp.js (which can automatically compress images and CSS and JavaScript files) and Bower (which makes it quick and easy to download common JavaScript libraries like jQuery, jQuery UI, or AngularJS to your computer).

JavaScript is also becoming increasingly popular for server-side development. The Node.js platform (a version of Google’s V8 JavaScript engine that runs JavaScript on the server) is being embraced eagerly by companies like Walmart, PayPal, and eBay. Learning JavaScript can even lead to a career in building complex server-side applications. In fact, the combination of JavaScript on the frontend (that is, JavaScript running in a web browser) and the backend (on the web server) is known as full stack JavaScript development.

In other words, there’s never been a better time to learn JavaScript!

JavaScript has one embarrassing little secret: writing it can be hard. While it’s simpler than many other programming languages, JavaScript is still a programming language. And many people, including web designers, find programming difficult. To complicate matters further, different web browsers understand JavaScript differently, so a program that works in, say, Chrome may be completely unresponsive in Internet Explorer 9. This common situation can cost many hours of testing on different machines and different browsers to make sure a program works correctly for your site’s entire audience.

That’s where jQuery comes in. jQuery is a JavaScript library intended to make JavaScript programming easier and more fun. A JavaScript library is a complex set of JavaScript code that both simplifies difficult tasks and solves cross-browser problems. In other words, jQuery solves the two biggest JavaScript headaches: complexity and the finicky nature of different web browsers.

jQuery is a web designer’s secret weapon in the battle of JavaScript programming. With jQuery, you can accomplish tasks in a single line of code that could take hundreds of lines of programming and many hours of browser testing to achieve with your own JavaScript code. In fact, an in-depth book solely about JavaScript would be at least twice as thick as the one you’re holding; and, when you were done reading it (if you could manage to finish it), you wouldn’t be able to do half of the things you can accomplish with just a little bit of jQuery knowledge.

That’s why most of this book is about jQuery. It lets you do so much, so easily. Another great thing about jQuery is that you can add advanced features to your website with thousands of easy-to-use jQuery plug-ins. For example, the jQuery UI plug-in (which you’ll meet on What Is jQuery UI?) lets you create many complex user interface elements like tabbed panels, drop-down menus, pop-up date-picker calendars—all with a single line of programming!

Unsurprisingly, jQuery is used on millions of websites (http://trends.builtwith.com/javascript/jQuery). It’s baked right into popular content management systems like Drupal and WordPress. You can even find job listings for “jQuery Programmers” with no mention of JavaScript. When you learn jQuery, you join a large community of fellow web designers and programmers who use a simpler and more powerful approach to creating interactive, powerful web pages.

JavaScript isn’t much good without the two other pillars of web design—HTML and CSS. Many programmers talk about the three languages as forming the “layers” of a web page: HTML provides the structural layer, organizing content like pictures and words in a meaningful way; CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) provides the presentational layer, making the content in the HTML look good; and JavaScript adds a behavioral layer, bringing a web page to life so it interacts with web visitors.

In other words, to master JavaScript, you need to have a good understanding of both HTML and CSS.

Note

For a full-fledged introduction to HTML and CSS, check out Head First HTML with CSS and XHTML by Elisabeth Robson and Eric Freeman. For an in-depth presentation of the tricky subject of Cascading Style Sheets, pick up a copy of CSS3: The Missing Manual by David Sawyer McFarland (both from O’Reilly).

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) uses simple commands called tags to define the various parts of a web page. For example, this HTML code creates a simple web page:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <meta charset=utf-8> <title>Hey, I am the title of this web page.</title> </head> <body> Hey, I am some body text on this web page. </body> </html>

It may not be exciting, but this example has all the basic elements a web page needs. This page begins with a single line—the document type declaration, or doctype for short—that states what type of document the page is and which standards it conforms to. HTML actually comes in different versions, and you use a different doctype with each. In this example, the doctype is for HTML5; the doctype for an HTML 4.01 or XHTML document is longer and also includes a URL that points the web browser to a file on the Internet that contains definitions for that type of file.

In essence, the doctype tells the web browser how to display the page. The doctype can even affect how CSS and JavaScript work. With an incorrect or missing doctype, you may end up banging your head against a wall as you discover lots of cross-browser differences with your scripts. If for no other reason, always include a doctype in your HTML.

Historically, there have been many doctypes—HTML 4.01 Transitional, HTML 4.01 Strict, XHTML 1.0 Transitional, XHTML 1.0 Strict—but they required a long line of confusing code that was easy to mistype. HTML5’s doctype—<!DOCTYPE html>—is short, simple, and the one you should use.

In the example in the previous section, as in the HTML code of any web page, you’ll notice that most instructions appear in pairs that surround a block of text or other commands. Sandwiched between brackets, these tags are instructions that tell a web browser how to display the web page. Tags are the “markup” part of the Hypertext Markup Language.

The starting (opening) tag of each pair tells the browser where the instruction begins, and the ending tag tells it where the instruction ends. Ending or closing tags always include a forward slash (/) after the first bracket symbol (<). For example, the tag <p> marks the start of a paragraph, while </p> marks its end. Some tags don’t have closing tags, like <img>, <input>, and <br> tags, which consist of just a single tag.

For a web page to work correctly, you must include at least these three tags:

The

<html>tag appears once at the beginning of a web page (after the doctype) and again (with an added slash) at the end. This tag tells a web browser that the information contained in this document is written in HTML, as opposed to some other language. All of the contents of a page, including other tags, appear between the opening and closing<html>tags.If you were to think of a web page as a tree, the

<html>tag would be its root. Springing from the root are two branches that represent the two main parts of any web page—the head and the body.The head of a web page, surrounded by

<head>tags, contains the title of the page. It may also provide other, invisible information (such as search keywords) that browsers and web search engines can exploit.In addition, the head can contain information that’s used by the web browser for displaying the web page and for adding interactivity. You put Cascading Style Sheets, for example, in the head of the document. The head of the document is also where you often include JavaScript programming and links to JavaScript files.

The body of a web page, as set apart by its surrounding

<body>tags, contains all the information that appears inside a browser window: headlines, text, pictures, and so on.

Within the <body> tag, you commonly find tags like the following:

You tell a web browser where a paragraph of text begins with a

<p>(opening paragraph tag), and where it ends with a</p>(closing paragraph tag).The

<strong>tag emphasizes text. If you surround some text with it and its partner tag,</strong>, you get boldface type. The HTML snippet<strong>Warning!</strong>tells a web browser to display the word “Warning!” in bold type.The

<a>tag, or anchor tag, creates a hyperlink in a web page. When clicked, a hyperlink—or link—can lead anywhere on the Web. You tell the browser where the link points by putting a web address inside the <a> tags. For instance, you might type<a href=“http://www.missingmanuals.com”>Click here!</a>.The browser knows that when your visitor clicks the words “Click here!” it should go to the Missing Manuals website. The

hrefpart of the tag is called an attribute and the URL (the uniform resource locator or web address) is the value. In this example, http://www.missingmanuals.com is the value of thehrefattribute.

At the beginning of the Web, HTML was the only language you needed to know. You could build pages with colorful text and graphics and make words jump out using different sizes, fonts, and colors. But today, web designers turn to Cascading Style Sheets to add visual sophistication to their pages. CSS is a formatting language that lets you make text look good, build complex page layouts, and generally add style to your site.

Think of HTML as merely the language you use to structure a page. It helps identify the stuff you want the world to know about. Tags like <h1> and <h2> denote headlines and assign them relative importance: A heading 1 is more important than a heading 2. The <p> tag indicates a basic paragraph of information. Other tags provide further structural clues: for example, a <ul> tag identifies a bulleted list (to make a list of recipe ingredients more intelligible, for example).

CSS, on the other hand, adds design flair to well-organized HTML content, making it more beautiful and easier to read. Essentially, a CSS style is just a rule that tells a web browser how to display a particular element on a page. For example, you can create a CSS rule to make all <h1> tags appear 36 pixels tall, in the Verdana font, and in orange. CSS can do more powerful stuff, too, like add borders, change margins, and even control the exact placement of a page element.

When it comes to JavaScript, some of the most valuable changes you make to a page involve CSS. You can use JavaScript to add or remove a CSS style from an HTML tag, or dynamically change CSS properties based on a visitor’s input or mouse clicks. You can even animate from the properties of one style to the properties of another (say, animating a background color changing from yellow to red). For example, you can make a page element appear or disappear simply by changing the CSS display property. To animate an item across the screen, you can change the CSS position properties dynamically using JavaScript.

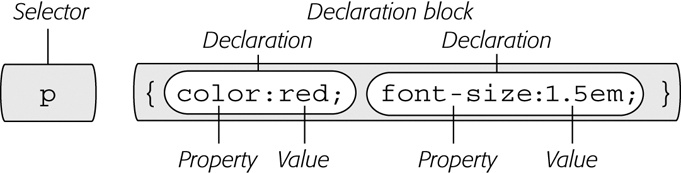

A single style that defines the look of one element is a pretty basic beast. It’s essentially a rule that tells a web browser how to format something—turn a headline blue, draw a red border around a photo, or create a 150-pixel-wide sidebar box to hold a list of links. If a style could talk, it would say something like, “Hey, Browser, make this look like that.” A style is, in fact, made up of two elements: the web page element that the browser formats (the selector) and the actual formatting instructions (the declaration block). For example, a selector can be a headline, a paragraph of text, a photo, and so on. Declaration blocks can turn that text blue, add a red border around a paragraph, position the photo in the center of the page—the possibilities are endless.

Note

Technical types often follow the lead of the W3C and call CSS styles rules. This book uses the terms “style” and “rule” interchangeably.

Of course, CSS styles can’t communicate in nice, clear English. They have their own language. For example, to set a standard font color and font size for all paragraphs on a web page, you’d write the following:

p { color: red; font-size: 1.5em; }This style simply says, “Make the text in all paragraphs—marked with <p> tags—red and 1.5 ems tall.” (An em is a unit or measurement that’s based on a browser’s normal text size.) As Figure 1 illustrates, even a simple style like this example contains several elements:

Selector. The selector tells a web browser which element or elements on a page to style—like a headline, paragraph, image, or link. In Figure 1, the selector (

p) refers to the<p>tag, which makes web browsers format all<p>tags using the formatting directions in this style. With the wide range of selectors that CSS offers and a little creativity, you can gain fine control of your pages’ formatting. (Selectors are an important part of using jQuery, so you’ll find a detailed discussion of them starting on Selecting Page Elements: The jQuery Way.)Declaration block. The code following the selector includes all the formatting options you want to apply to the selector. The block begins with an opening brace ({) and ends with a closing brace (}).

Declaration. Between the opening and closing braces of a declaration, you add one or more declarations, or formatting instructions. Every declaration has two parts, a property and a value, and ends with a semicolon. A colon separates the property name from its value:

color : red;.Property. CSS offers a wide range of formatting options, called properties. A property is a word—or a few hyphenated words—indicating a certain style effect. Most properties have straightforward names like

font-size,margin-top, andbackground-color. For example, thebackground-colorproperty sets—you guessed it—a background color.Value. Finally, you get to express your creative genius by assigning a value to a CSS property—by making a background blue, red, purple, or chartreuse, for example. Different CSS properties require specific types of values—a color (like

red, or#FF0000), a length (like18px,2in,or 5em), a URL (like images/background.gif), or a specific keyword (liketop,center,or bottom).

Figure 1. A style (or rule) is made of two main parts: a selector, which tells web browsers what to format, and a declaration block, which lists the formatting instructions that the browsers use to style the selector.

You don’t need to write a style on a single line as pictured in Figure 1. Many styles have multiple formatting properties, so you can make them easier to read by breaking them up into multiple lines. For example, you may want to put the selector and opening brace on the first line, each declaration on its own line, and the closing brace by itself on the last line, like so:

p {

color: red;

font-size: 1.5em;

}It’s also helpful to indent properties, with either a tab or a couple of spaces, to visibly separate the selector from the declarations, making it easy to tell which is which. And finally, putting one space between the colon and the property value is optional, but adds to the readability of the style. In fact, you can put as much white space between the two as you want. For example, color:red, color: red, and color : red all work.

To create web pages made up of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, you need nothing more than a basic text editor like Notepad (Windows) or TextEdit (Mac). But after typing a few hundred lines of JavaScript code, you may want to try a program better suited to working with web pages. This section lists some common editors—some free and some you can buy.

Note

There are literally hundreds of tools that can help you create web pages and write JavaScript programs, so the following is by no means a complete list. Think of it as a greatest-hits tour of the most popular programs that JavaScript fans are using today.

There are plenty of free programs out there for editing web pages and style sheets. If you’re still using Notepad or TextEdit, give one of these a try. Here’s a short list to get you started:

Brackets (Windows, Mac, and Linux, http://brackets.io) is an open source code editor from Adobe. It’s free (there is a commercial version with more features named Edge Code), has many great features including a great live browser preview, and is even written in JavaScript!

Notepad++ (Windows, http://notepad-plus-plus.org) is a coder’s friend. It highlights the syntax of JavaScript and HTML code, and lets you save macros and assign keyboard shortcuts to them so you can automate the process of inserting the code snippets you use most.

HTML-Kit (Windows, www.chami.com/html-kit) is a powerful HTML/XHTML editor that includes lots of useful features, like the ability to preview a web page directly in the program (so you don’t have to switch back and forth between browser and editor), shortcuts for adding HTML tags, and a lot more.

CoffeeCup Free HTML Editor (Windows, www.coffeecup.com/free-editor) is the free version of the commercial ($49) CoffeeCup HTML editor.

TextWrangler (Mac, www.barebones.com/products/textwrangler) is free software that’s actually a pared-down version of BBEdit, the sophisticated, well-known text editor for the Mac. TextWrangler doesn’t have all of BBEdit’s built-in HTML tools, but it does include syntax coloring (highlighting tags and properties in different colors so it’s easy to scan a page and identify its parts), FTP support (so you can upload files to a web server), and more.

Eclipse (Windows, Linux, and Mac, www.eclipse.org) is a free, popular choice among Java Developers, but includes tools for working with HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. A version specifically for JavaScript developers is also available (www.eclipse.org/downloads/packages/eclipse-ide-javascript-web-developers/indigor), as well as Eclipse plug-ins to add autocomplete for jQuery (http://marketplace.eclipse.org/category/free-tagging/jquery).

Aptana Studio (Windows, Linux, and Mac, www.aptana.org) is a powerful, free coding environment with tools for working with HTML, CSS, JavaScript, PHP, and Ruby on Rails.

Vim and Emacs are tried and true text editors from the Unix world. They’re included with OS X and Linux, and you can download versions for Windows. They’re loved by serious programmers, but have a steep learning curve for most people.

Commercial website development programs range from inexpensive text editors to complete website construction tools with all the bells and whistles:

Atom (Windows and Mac, https://atom.io) is a new kid on the block. It’s not yet available for sale, but the beta version is free for now. Atom is developed by the folks at GitHub (a site for sharing and collaboratively working on projects), and offers a large array of features built specifically for the needs of today’s developers. It features a modular design, which allows for lots of third-party plug-ins that enhance the program’s functionality.

SublimeText (Windows, Mac, and Linux, https://www.sublimetext.com) is a darling of many programmers. This text editor ($70) includes many timesaving features for JavaScript programmers, like “auto-paired characters,” which automatically plops in the second character of a pair of punctuation marks (for example, the program automatically inserts a closing parenthesis after you type an opening parenthesis).

EditPlus (Windows, www.editplus.com) is an inexpensive text editor ($35) that includes syntax coloring, FTP, autocomplete, and other wrist-saving features.

BBEdit (Mac, www.barebones.com/products/bbedit). This much-loved Mac text editor ($99.99) has plenty of tools for working with HTML, XHTML, CSS, JavaScript, and more. It includes many useful web building tools and shortcuts.

Dreamweaver (Mac and Windows, www.adobe.com/products/dreamweaver.html) is a visual web page editor ($399). It lets you see how your page looks in a web browser. The program also includes a powerful text editor for writing JavaScript programs and excellent CSS creation and management tools. Check out Dreamweaver CC: The Missing Manual for the full skinny on how to use this powerful program.

Unlike a piece of software such as Microsoft Word or Dreamweaver, JavaScript isn’t a single product developed by a single company. There’s no support department at JavaScript headquarters writing an easy-to-read manual for the average web developer. While you’ll find plenty of information on sites like Mozilla.org (see, for example, https://developer.mozilla.org/en/JavaScript/Reference or www.ecmascript.org), there’s no definitive source of information on the JavaScript programming language.

Because there’s no manual for JavaScript, people just learning JavaScript often don’t know where to begin. And the finer points regarding JavaScript can trip up even seasoned web pros. The purpose of this book, then, is to serve as the manual that should have come with JavaScript. In this book’s pages, you’ll find step-by-step instructions for using JavaScript to create highly interactive web pages.

Likewise, you’ll find good documentation on jQuery at http://api.jquery.com. But it’s written by programmers for programmers, and so the explanations are mostly brief and technical. And while jQuery is generally more straightforward than regular JavaScript programming, this book will teach you fundamental jQuery principles and techniques so you can start off on the right path when enhancing your websites with jQuery.

JavaScript & jQuery: The Missing Manual is designed to accommodate readers who have some experience building web pages. You’ll need to feel comfortable with HTML and CSS to get the most from this book, because JavaScript often works closely with HTML and CSS to achieve its magic. The primary discussions are written for advanced-beginner or intermediate computer users. But if you’re new to building web pages, special boxes called Up to Speed provide the introductory information you need to understand the topic at hand. If you’re an advanced web page jockey, on the other hand, keep your eye out for similar shaded boxes called Power Users’ Clinic. They offer more technical tips, tricks, and shortcuts for the experienced computer fan.

Note

This book periodically recommends other books, covering topics that are too specialized or tangential for a manual about using JavaScript. Sometimes the recommended titles are from Missing Manual series publisher O’Reilly Media—but not always. If there’s a great book out there that’s not part of the O’Reilly family, we’ll let you know about it.

JavaScript is a real programming language: It doesn’t work like HTML or CSS, and it has its own set of (often complicated) rules. It’s not always easy for web designers to switch gears and start thinking like computer programmers, and there’s no one book that can teach you everything there is to know about JavaScript.

The goal of JavaScript & jQuery: The Missing Manual isn’t to turn you into the next great programmer (though it might start you on your way). This book is meant to familiarize web designers with the ins and outs of JavaScript and then move on to jQuery so that you can add really useful interactivity to a website as quickly and easily as possible.

In this book, you’ll learn the basics of JavaScript and programming; but just the basics won’t make for very exciting web pages. It’s not possible in 500 pages to teach you everything about JavaScript that you need to know to build sophisticated, interactive web pages. Instead, much of this book will cover the wildly popular jQuery JavaScript library, which, as you’ll soon learn, will liberate you from all of the minute, time-consuming details of creating JavaScript programs that run well across different browsers.

You’ll learn the basics of JavaScript, and then jump immediately to advanced web page interactivity with a little help—OK, a lot of help—from jQuery. Think of it this way: You could build a house by cutting down and milling your own lumber, constructing your own windows, doors, and doorframes, manufacturing your own tile, and so on. That do-it-yourself approach is common to a lot of JavaScript books. But who has that kind of time? This book’s approach is more like building a house by taking advantage of already-built pieces and putting them together using basic skills. The end result will be a beautiful and functional house built in a fraction of the time it would take you to learn every step of the process.

JavaScript & jQuery: The Missing Manual is divided into five parts, each containing several chapters:

Part 1 starts at the very beginning. You’ll learn the basic building blocks of JavaScript as well as get some helpful tips on computer programming in general. This section teaches you how to add a script to a web page, store and manipulate information, and add smarts to a program so it can respond to different situations. You’ll also learn how to communicate with the browser window, store and read cookies, respond to various events like mouse clicks and form submissions, and modify the HTML of a web page.

Part 2 introduces jQuery—the Web’s most popular JavaScript library. Here you’ll learn the basics of this amazing programming tool that will make you a more productive and capable JavaScript programmer. You’ll learn how to select and manipulate page elements, add interaction by making page elements respond to your visitors, and add flashy visual effects and animations.

Part 3 covers jQuery’s sister project, jQuery UI. jQuery UI is a JavaScript library of helpful “widgets” and effects. It makes adding common user interface elements like tabbed panels, dialog boxes, accordions, drop-down menus really easy. jQuery UI can help you build a unified-looking and stylish user interface for your next big web application.

Part 4 looks at some advanced uses of jQuery and JavaScript. In particular, Chapter 13 covers the technology that single-handedly made JavaScript one of the most glamorous web languages to learn. In this chapter, you’ll learn how to use JavaScript to communicate with a web server so your pages can receive information and update themselves based on information provided by a web server—without having to load a new web page. Chapter 14 guides you step by step in creating a to-do list application using jQuery and jQuery UI.

Part 5 takes you past the basics, covering more complex concepts. You’ll learn more about how to use jQuery effectively, as well as delve into advanced JavaScript concepts. This part of the book also helps you when nothing seems to be working: when your perfectly crafted JavaScript program just doesn’t seem to do what you want (or worse, it doesn’t work at all!). You’ll learn the most common errors new programmers make as well as techniques for discovering and fixing bugs in your programs.

At the end of the book, an appendix provides a detailed list of references to aid you in your further exploration of the JavaScript programming language.

To use this book, and indeed to use a computer, you need to know a few basics. This book assumes that you’re familiar with a few terms and concepts:

Clicking. This book gives you three kinds of instructions that require you to use your computer’s mouse or trackpad. To click means to point the arrow cursor at something on the screen and then—without moving the cursor at all—to press and release the clicker button on the mouse (or laptop trackpad). To right-click means to do the same thing with the right mouse button. To double-click, of course, means to click twice in rapid succession, again without moving the cursor at all. And to drag means to move the cursor while pressing the button.

Tip

If you’re on a Mac and don’t have a right mouse button, you can accomplish the same thing by pressing the Control key as you click with the one mouse button.

When you’re told to ⌘-click something on the Mac, or Ctrl-click something on a PC, you click while pressing the ⌘ or Ctrl key (both of which are near the space bar).

Menus. The menus are the words at the top of your screen or window: File, Edit, and so on. Click one to make a list of commands appear, as though they’re written on a window shade you’ve just pulled down.

Keyboard shortcuts. If you’re typing along in a burst of creative energy, it’s sometimes disruptive to have to take your hand off the keyboard, grab the mouse, and then use a menu (for example, to use the Bold command). That’s why many experienced computer mavens prefer to trigger menu commands by pressing certain combinations on the keyboard. For example, in the Firefox web browser, you can press Ctrl-+ (Windows) or ⌘-+ (Mac) to make text on a web page get larger (and more readable). When you read an instruction like “press ⌘-B,” start by pressing the ⌘-key; while it’s down, type the letter B, and then release both keys.

Operating system basics. This book assumes that you know how to open a program, surf the Web, and download files. You should know how to use the Start menu (Windows) and the Dock or Apple menu (Macintosh), as well as the Control Panel (Windows), or System Preferences (Mac OS X).

If you’ve mastered this much information, you have all the technical background you need to enjoy JavaScript & jQuery: The Missing Manual.

Throughout this book, and throughout the Missing Manual series, you’ll find sentences like this one: “Open the System→Library→Fonts.” That’s shorthand for a much longer instruction that directs you to open three nested folders in sequence, like this: “On your hard drive, you’ll find a folder called System. Open that. Inside the System folder window is a folder called Library; double-click it to open it. Inside that folder is yet another one called Fonts. Double-click to open it, too.”

Similarly, this kind of arrow shorthand helps to simplify the business of choosing commands in menus, as shown in Figure 2.

This book is designed to get your work onto the Web faster and more professionally; it’s only natural, then, that much of the value of this book also lies on the Web. Online, you’ll find example files so you can get some hands-on experience. You can also communicate with the Missing Manual team and tell us what you love (or hate) about the book. Head over to www.missingmanuals.com, or go directly to one of the following sections.

As you read the book’s chapters, you’ll encounter a number of living examples—step-by-step tutorials that you can build yourself, using raw materials (like graphics and half-completed web pages) that you can download from either https://github.com/sawmac/js3e or from this book’s Missing CD page at http://www.missingmanuals.com/cds. You might not gain very much from simply reading these step-by-step lessons while relaxing in your porch hammock, but if you take the time to work through them at the computer, you’ll discover that these tutorials give you unprecedented insight into the way professional designers build web pages.

You’ll also find, in this book’s lessons, the URLs of the finished pages, so that you can compare your work with the final result. In other words, you won’t just see pictures of JavaScript code in the pages of the book; you’ll find the actual, working web pages on the Internet.

If you register this book at http://oreilly.com, you’ll be eligible for special offers—like discounts on future editions of JavaScript & jQuery: The Missing Manual. Registering takes only a few clicks. To get started, type www.oreilly.com/register into your browser to hop directly to the Registration page.

Got questions? Need more information? Fancy yourself a book reviewer? On our Feedback page, you can get expert answers to questions that come to you while reading, share your thoughts on this Missing Manual, and find groups for folks who share your interest in JavaScript and jQuery. To have your say, go to www.missingmanuals.com/feedback.

In an effort to keep this book as up to date and accurate as possible, each time we print more copies, we’ll make any confirmed corrections you’ve suggested. We also note such changes on the book’s website, so you can mark important corrections into your own copy of the book, if you like. Go to http://tinyurl.com/jsjq3-mm to report an error and view existing corrections.

Safari® Books Online is an on-demand digital library that lets you easily search over 7,500 technology and creative reference books and videos to find the answers you need quickly.

With a subscription, you can read any page and watch any video from our library online. Read books on your cellphone and mobile devices. Access new titles before they’re available for print, and get exclusive access to manuscripts in development and post feedback for the authors. Copy and paste code samples, organize your favorites, download chapters, bookmark key sections, create notes, print out pages, and benefit from tons of other time-saving features.

Get JavaScript & jQuery: The Missing Manual, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.