A popular aim for games is to be an immersive experience, where the player becomes so enthralled with the game that he or she forgets everyday trivia such as eating and visiting the bathroom. One simple way of encouraging immersion is to make the game window the size of the desktop; a full-screen display hides tiresome text editors, spreadsheets, or database applications requiring urgent attention.

I'll look at three approaches to creating full-screen games:

An almost full-screen

JFrame(I'll call this AFS)An undecorated full-screen

JFrame(UFS)Full-screen exclusive mode (FSEM)

FSEM is getting a lot of attention since its introduction in J2SE 1.4 because it has increased frame rates over traditional gaming approaches using repaint events and paintComponent(). However, comparisons between AFS, UFS, and FSEM show their maximum frame rates to be similar. This is due to my use of the animation loop developed in Chapter 2, with its active rendering and high-resolution Java 3D timer. You should read Chapter 2 before continuing.

The examples in this chapter will continue using the WormChase game, first introduced in Chapter 3, so you'd better read that chapter as well. By sticking to a single game throughout this chapter, the timing comparisons more accurately reflect differences in the animation code rather than in the game-specific parts.

The objective is to produce 80 to 85 FPS, which is near the limit of a typical graphics card's rendering capacity. If the game's frame rate falls short of this, then the updates per second (UPS) should still stay close to 80 to 85, causing the game to run quickly but without every update being rendered.

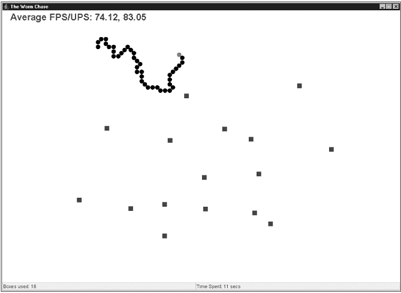

Figure 4-1 shows the WormChase application running inside a JFrame that almost covers the entire screen. The JFrame's titlebar, including its close box and iconification/de-iconfication buttons are visible, and a border is around the window. The OS desktop controls are visible (in this case, Windows's task bar at the bottom of the screen).

These JFrame and OS components allow the player to control the game (e.g., pause it by iconification) and to switch to other applications in the usual way, without the need for GUI controls inside the game. Also, little code has to be modified to change a windowed game into an AFS version, aside from resizing the canvas.

Though the window can be iconified and switched to the background, it can't be moved. To be more precise, it can be selected and dragged, but as soon as the mouse button is released, the window snaps back to its original position.

Tip

This is a fun effect, as if the window is attached by a rubber band to the top lefthand corner of the screen.

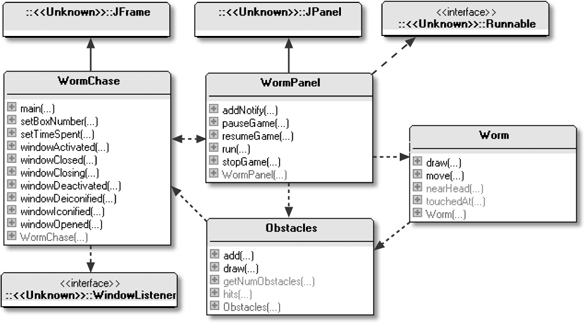

Figure 4-2 gives the class diagrams for the AFS version of WormChase, including the public methods.

The AFS approach and the windowed application are similar as shown by the class diagrams in Figure 4-2 being identical to those for the windowed WormChase application at the start of Chapter 3. The differences are located in the private methods and the constructor, where the size of the JFrame is calculated and listener code is put in place to keep the window from moving.

WormPanel is almost the same as before, except that WormChase passes it a calculated width and height (in earlier version these were constants in the class). The Worm and Obstacles classes are unaltered from Chapter 3.

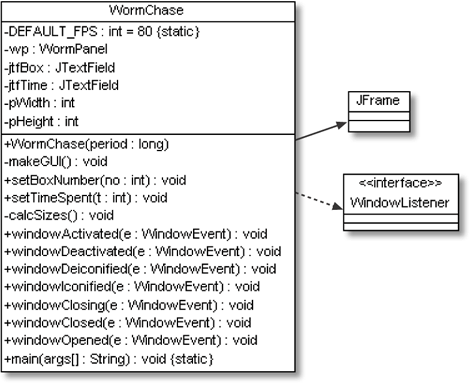

Figure 4-3 gives a class diagram for WormChase showing all its variables and methods.

The constructor has to work hard to obtain correct dimensions for the JPanel. The problem is that the sizes of three distinct kinds of elements must be calculated:

The

JFrame's insets (e.g., the titlebar and borders)The desktop's insets (e.g., the taskbar)

The other Swing components in the window (e.g., two text fields)

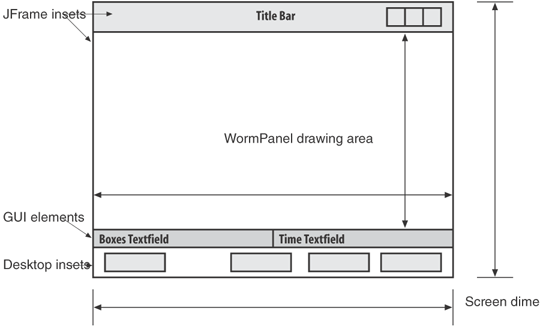

The insets of a container are the unused areas around its edges (at the top, bottom, left, and right). Typical insets are the container's border lines and its titlebar. The widths and heights of these elements must be subtracted from the screen's dimensions to get WormPanel's width and height. Figure 4-4 shows the insets and GUI elements for WormChase.

The subtraction of the desktop and JFrame inset dimensions from the screen size is standard, but the calculation involving the on-screen positions of the GUI elements depends on the game design. For WormChase, only the heights of the text fields affect WormPanel's size.

A subtle problem is that the dimensions of the JFrame insets and GUI elements will be unavailable until the game window has been constructed. In that case, how can the panel's dimensions be calculated if the application has to be created first?

The answer is that the application must be constructed in stages. First, the JFrame and other pieces needed for the size calculations are put together. This fixes their sizes, so the drawing panel's area can be determined. The sized JPanel is then added to the window to complete it, and the window is made visible. The WormChase constructor utilizes these stages:

public WormChase(long period)

{ super("The Worm Chase");

makeGUI(); pack(); // first pack (the GUI doesn't include the JPanel yet)

setResizable(false); //so sizes are for nonresizable GUI elems

calcSizes();

setResizable(true); // so panel can be added

Container c = getContentPane();

wp = new WormPanel(this, period, pWidth, pHeight);

c.add(wp, "Center");

pack(); // second pack, after JPanel added

addWindowListener( this );

addComponentListener( new ComponentAdapter() {

public void componentMoved(ComponentEvent e)

{ setLocation(0,0); }

});

setResizable(false);

setVisible(true);

} // end of WormChase() constructor

makeGUI() builds the GUI without a drawing area, and the call to pack() makes the JFrame displayable and calculates the component's sizes. Resizing is turned off since some platforms render insets differently (i.e., with different sizes) when their enclosing window can't be resized.

calcSizes() initializes two globals, pWidth and pHeight, which are later passed to the WormPanel constructor as the panel's width and height:

private void calcSizes()

{

GraphicsConfiguration gc = getGraphicsConfiguration();

Rectangle screenRect = gc.getBounds(); // screen dimensions

Toolkit tk = Toolkit.getDefaultToolkit();

Insets desktopInsets = tk.getScreenInsets(gc);

Insets frameInsets = getInsets(); // only works after pack()

Dimension tfDim = jtfBox.getPreferredSize(); // textfield size

pWidth = screenRect.width

- (desktopInsets.left + desktopInsets.right)

- (frameInsets.left + frameInsets.right);

pHeight = screenRect.height

- (desktopInsets.top + desktopInsets.bottom)

- (frameInsets.top + frameInsets.bottom)

- tfDim.height;

}Tip

If the JFrame's insets (stored in frameInsets) are requested before a call to pack(), then they will have zero size.

An Insets object has four public variables—top, bottom, left, and right—that hold the thickness of its container's edges. Only the dimensions for the box's text field (jtfBox) is retrieved since its height will be the same as the time-used text field. Back in WormChase(), resizing is switched back on so the correctly sized JPanel can be added to the JFrame. Finally, resizing is switched off permanently, and the application is made visible with a call to show().

Unfortunately, there is no simple way of preventing an application's window from being dragged around the screen. The best you can do is move it back to its starting position as soon as the user releases the mouse.

The WormChase constructor sets up a component listener with a componentMoved() handler. This method is called whenever a move is completed:

addComponentListener( new ComponentAdapter() {

public void componentMoved(ComponentEvent e)

{ setLocation(0,0); }

});

setLocation() positions the JFrame so its top-left corner is at the top left of the screen.

Timing results for the AFS WormChase are given in Table 4-1.

Table 4-1. Average FPS/UPS rates for the AFS WormChase

|

Requested FPS |

20 |

50 |

80 |

100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Windows 98 |

20/20 |

49/50 |

75/83 |

86/100 |

|

Windows 2000 |

20/20 |

20/50 |

20/83 |

20/100 |

|

Windows XP (1) |

20/20 |

50/50 |

82/83 |

87/100 |

|

Windows XP (2) |

20/20 |

50/50 |

75/83 |

75/100 |

WormChase on the slow Windows 2000 machine is the worst performer again, as seen in Chapter 3, though its slowness is barely noticeable due to the update rate remaining high.

The Windows 98 and XP boxes produce good frame rates when 80 FPS is requested, which is close to or inside my desired range (80 to 85 FPS). The numbers start to flatten as the FPS request goes higher, indicating that the frames can't be rendered any faster.

Get Killer Game Programming in Java now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.