This chapter begins our introduction to the Java language syntax. Since readers come to this book with different levels of programming experience, it is difficult to set the right level for all audiences. We have tried to strike a balance between a thorough tour of the language syntax for beginners and providing enough background information so that a more experienced reader can quickly gauge the differences between Java and other languages. Since Java’s syntax is derived from C, we make some comparisons to features of that language, but no special knowledge of C is necessary. We spend more time on aspects of Java that are different from other languages and less on elemental programming concepts. For example, we’ll take a close look at arrays in Java because they are significantly different from those in other languages. We won’t, on the other hand, spend as much time explaining basic language constructs such as loops and control structures. Chapters 5 through 7 will build on this chapter by talking about Java’s object-oriented side and complete the discussion of the core language. Chapter 8 discusses generics, a Java 5.0 feature that enhances the way types work in the Java language, allowing you to write certain kinds of classes more flexibly and safely. After that, we dive into the Java APIs and see what we can do with the language. The rest of this book is filled with concise examples that do useful things and if you are left with any questions after these introductory chapters, we hope they’ll be answered by real world usage.

Java is a language for the Internet. Since the people of the Net speak and write in many different human languages, Java must be able to handle a large number of languages as well. One of the ways in which Java supports internationalization is through the Unicode character set. Unicode is a worldwide standard that supports the scripts of most languages.[*] Java bases its character and string data on the Unicode 4.0 standard, which uses 16 bits to represent each symbol.

Java source code can be written using Unicode and stored in any number of character encodings, ranging from its full 16-bit form to ASCII-encoded Unicode character values. This makes Java a friendly language for non-English-speaking programmers who can use their native language for class, method, and variable names just as they can for the text displayed by the application.

The Java char type and String objects natively support Unicode values. But if you’re

concerned about having to labor with two-byte characters, you can relax. The String

API makes the character encoding transparent to you. Unicode is also very

ASCII-friendly (ASCII is the most common character encoding for English). The first

256 characters are defined to be identical to the first 256 characters in the ISO

8859-1 (Latin-1) character set, so Unicode is effectively backward-compatible with

the most common English character sets. Furthermore, the most common encoding for

Unicode, called UTF-8, preserves ASCII values in their single byte form. This

encoding is used in compiled Java class files, so for English text, storage remains

compact.

Most platforms can’t display all currently defined Unicode characters. As a result, Java programs can be written with special Unicode escape sequences. A Unicode character can be represented with this escape sequence:

\uxxxxxxxx is a sequence of one to four hexadecimal digits.

The escape sequence indicates an ASCII-encoded Unicode character. This is also the

form Java uses to output (print) Unicode characters in an environment that doesn’t

otherwise support them. Java also comes with classes to read and write Unicode

character streams in specific encodings, including UTF-8.

Java supports both C-style

block comments

delimited by /* and */ and C++-style

line comments indicated by //:

/* This is a

multiline

comment. */

// This is a single-line comment

// and so // is thisBlock comments have

both a beginning and end sequence and can cover large ranges of text. However, they

cannot be “nested”; meaning that you can’t have a block comment inside of a block

comment without the compiler getting confused. Single-line comments have only a

start sequence and are delimited by the end of a line; extra // indicators inside a single line have no effect.

Line comments are useful for short comments within methods; they don’t conflict with

block comments, so you can still comment-out larger chunks of code including

them.

A block comment beginning with /** indicates a special doc

comment. A doc comment is designed to be extracted by automated

documentation generators, such as the JDK’s javadoc

program. A doc comment is terminated by the next */, just as with a regular block comment. Within the doc comment,

lines beginning with @ are interpreted as

special instructions for the documentation generator, giving it information

about the source code. By convention, each line of a doc comment begins with a

*, as shown in the following example, but

this is optional. Any leading spacing and the * on each line are ignored:

/**

* I think this class is possibly the most amazing thing you will

* ever see. Let me tell you about my own personal vision and

* motivation in creating it.

* <p>

* It all began when I was a small child, growing up on the

* streets of Idaho. Potatoes were the rage, and life was good...

*

* @see PotatoPeeler

* @see PotatoMasher

* @author John 'Spuds' Smith

* @version 1.00, 19 Dec 2006

*/

class Potato {javadoc creates HTML documentation for classes by reading

the source code and pulling out the embedded comments and @ tags. In this example, the tags cause author and

version information to be presented in the class documentation. The @see tags produce hypertext links to the related

class documentation.

The compiler also looks at the doc comments; in

particular, it is interested in the @deprecated tag, which means that the method has been declared

obsolete and should be avoided in new programs. The fact that a method is

deprecated is noted in the compiled class file so a warning message can be

generated whenever you use a deprecated feature in your code (even if the source

isn’t available).

Doc comments can appear above class, method, and variable definitions, but

some tags may not be applicable to all of these. For example, the @exception tag can only be applied to methods.

Table 4-1 summarizes the

tags used in doc comments.

Table 4-1. Doc comment tags

|

Tag |

Description |

Applies to |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Associated class name |

Class, method, or variable |

|

|

Author name |

Class |

|

|

Version string |

Class |

|

|

Parameter name and description |

Method |

|

|

Description of return value |

Method |

|

|

Exception name and description |

Method |

|

|

Declares an item to be obsolete |

Class, method, or variable |

|

|

Notes API version when item was added |

Variable |

Javadoc

tags in doc comments represent metadata about the

source code; that is, they add descriptive information about the structure

or contents of the code that is not, strictly speaking, part of the

application. In the past, some additional tools have extended the concept of

Javadoc-style tags to include other kinds of metadata about Java programs.

Java 5.0 introduced a new annotations

facility

that provides a more formal and extensible way to add metadata to Java

classes, methods, and variables. We’ll talk about annotations in Chapter 7. However, we should mention

that there is an @deprecated annotation

that has the same meaning as that of the Javadoc tag of the same name. Users

of Java 5.0 will likely prefer it to the Javadoc form.

The type system of a programming language describes how its data elements (variables and constants) are associated with storage in memory and how they are related to one another. In a statically typed language, such as C or C++, the type of a data element is a simple, unchanging attribute that often corresponds directly to some underlying hardware phenomenon, such as a register or a pointer value. In a more dynamic language such as Smalltalk or Lisp, variables can be assigned arbitrary elements and can effectively change their type throughout their lifetime. A considerable amount of overhead goes into validating what happens in these languages at runtime. Scripting languages such as Perl achieve ease of use by providing drastically simplified type systems in which only certain data elements can be stored in variables, and values are unified into a common representation, such as strings.

Java combines the best features of both statically and dynamically typed languages. As in a statically typed language, every variable and programming element in Java has a type that is known at compile time, so the runtime system doesn’t normally have to check the validity of assignments between types while the code is executing. Unlike traditional C or C++, Java also maintains runtime information about objects and uses this to allow truly dynamic behavior. Java code may load new types at runtime and use them in fully object-oriented ways, allowing casting and full polymorphism (extending of types).

Java data types fall into two categories. Primitive types represent simple values that have built-in functionality in the language; they are fixed elements, such as literal constants and numbers. Reference types (or class types) include objects and arrays; they are called reference types because they “refer to” a large data type which is passed “by reference,” as we’ll explain shortly. In Java 5.0, generic types were introduced to the language, but they are really an extension of classes and are, therefore, actually reference types.

Numbers, characters, and Boolean values are fundamental elements in Java. Unlike some other (perhaps more pure) object-oriented languages, they are not objects. For those situations where it’s desirable to treat a primitive value as an object, Java provides “wrapper” classes. The major advantage of treating primitive values as special is that the Java compiler and runtime can more readily optimize their implementation. Primitive values and computations can still be mapped down to hardware as they always have been in lower-level languages. As of Java 5.0, the compiler can automatically convert between primitive values and their object wrappers as needed to partially mask the difference between the two. We’ll explain what that means in more detail in the next chapter when we discuss boxing and unboxing of primitive values.

An important portability feature of Java is that primitive types are precisely

defined. For example, you never have to worry about the size of an int on a particular platform; it’s always a

32-bit, signed, two’s complement number. Table 4-2 summarizes Java’s

primitive types.

Table 4-2. Java primitive data types

|

Type |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

16-bit, Unicode character |

|

|

8-bit, signed, two’s complement integer |

|

|

16-bit, signed, two’s complement integer |

|

|

32-bit, signed, two’s complement integer |

|

|

64-bit, signed, two’s complement integer |

|

|

32-bit, IEEE 754, floating-point value |

|

|

64-bit, IEEE 754 |

Those of you with a C background may notice that the primitive types look like an idealization of C scalar types on a 32-bit machine, and you’re absolutely right. That’s how they’re supposed to look. The 16-bit characters were forced by Unicode, and ad hoc pointers were deleted for other reasons. But overall, the syntax and semantics of Java primitive types are meant to fit a C programmer’s mental habits.

Floating-point

operations in Java follow the IEEE 754 international specification, which

means that the result of floating-point

calculations is normally the same on different Java platforms. However,

since Version 1.3, Java has allowed for extended precision on platforms that

support it. This can introduce extremely small-valued and arcane differences

in the results of high-precision operations. Most applications would never

notice this, but if you want to ensure that your application produces

exactly the same results on different platforms, you can use the special

keyword strictfp as a class modifier on

the class containing the floating-point manipulation (we cover classes in

the next chapter). The compiler then prohibits platform-specific

optimizations.

Variables are declared inside of methods or classes in C style, with a type followed by one or more comma-separated variable names. For example:

int foo;

double d1, d2;

boolean isFun;Variables can optionally be initialized with an appropriate expression when they are declared:

int foo = 42;

double d1 = 3.14, d2 = 2 * 3.14;

boolean isFun = true;Variables that are declared as members of a class are set to default

values if they aren’t initialized (see Chapter 5). In this case, numeric types default to the

appropriate flavor of zero, characters are set to the null

character (\0), and Boolean variables have the value

false

.

Local variables, which are declared inside a method and live only for the

duration of a method call, on the other hand, must be explicitly initialized

before they can be used. As we’ll see, the compiler enforces this rule so

there is no danger of forgetting.

Integer literals can be specified in octal (base 8), decimal (base 10), or hexadecimal (base 16). A decimal integer is specified by a sequence of digits beginning with one of the characters 1-9:

int i = 1230;

Octal numbers are distinguished from decimal numbers by a leading zero:

int i = 01230; // i = 664 decimal

A hexadecimal number is denoted by the leading characters 0x or 0X

(zero “x”), followed by a combination of digits and the characters a-f or

A-F, which represent the decimal values 10-15:

int i = 0xFFFF; // i = 65535 decimal

Integer literals are of type int unless

they are suffixed with an L, denoting

that they are to be produced as a long

value:

long l = 13L;

long l = 13; // equivalent: 13 is converted from type int(The lowercase letter l is also

acceptable but should be avoided because it often looks like the number

1.)

When a numeric type is used in an assignment or an expression involving a

“larger” type with a greater range, it can be promoted

to the bigger type. In the second line of the previous example, the number

13 has the default type of int, but it’s promoted to type long for assignment to the long variable. Certain other numeric and

comparison operations also cause this kind of arithmetic promotion, as do

mathematical expressions involving more than one type. For example, when

multiplying a byte value by an int value, the compiler promotes the byte to an int first:

byte b = 42;

int i = 43;

int result = b * i; // b is promoted to int before multiplicationA numeric value can never go the other way and be assigned to a type with a smaller range without an explicit cast, however:

int i = 13;

byte b = i; // Compile-time error, explicit cast needed

byte b = (byte) i; // OKConversions from floating-point to integer types always require an explicit cast because of the potential loss of precision.

In an object-oriented language like Java, you

create new, complex data types from simple primitives by creating a class. Each class then serves as a new type in the

language. For example, if we create a new class called Foo in Java, we are also implicitly creating a new type called

Foo. The type of an item governs how it’s

used and where it can be assigned. As with primitives, an item of type Foo can, in general, be assigned to a variable of

type Foo or passed as an argument to a method

that accepts a Foo value.

A type is not just a simple attribute. Classes can have relationships with

other classes and so do the types that they represent. All classes exist in a

parent-child hierarchy, where a child class or subclass is

a specialized kind of its parent class. The corresponding types have the same

relationship, where the type of the child class is considered a subtype of the

parent class. Because child classes inherit all of the functionality of their

parent classes, an object of the child’s type is in some sense equivalent to or

an extension of the parent type. An object of the child type can be used in

place of an object of the parent’s type. For example, if you create a new class,

Cat, that extends Animal, the new type, Cat, is considered a subtype of Animal. Objects of type Cat

can then be used anywhere an object of type Animal can be used; an object of type Cat is said to be assignable to a variable of type Animal. This is called subtype

polymorphism

and is one of the primary features of

an object-oriented language. We’ll look more closely at classes and objects in

Chapter 5.

Primitive types in Java are used and passed “by value.” In other words, when a

primitive value like an int is assigned to a

variable or passed as an argument to a method, it’s simply copied. Reference

types, on the other hand, are always accessed “by reference.” A

reference is simply a handle or a name for an object.

What a variable of a reference type holds is a “pointer” to an object of its

type (or of a subtype, as described earlier). When the reference is assigned or

passed to a method, only the reference is copied, not the object it’s pointing

to. A reference is like a pointer in C or C++, except that its type is so

strictly enforced that you can’t mess with the reference itself—it’s an atomic

entity. The reference value itself can’t be created or changed. A variable gets

assigned a reference value only through assignment to an appropriate

object.

Let’s run through an example. We declare a variable of type Foo, called myFoo, and assign it an appropriate object:[*]

Foo myFoo = new Foo();

Foo anotherFoo = myFoo;myFoo is a reference-type variable that

holds a reference to the newly constructed Foo object. (For now, don’t worry about the details of creating

an object; we’ll cover that in Chapter

5.) We declare a second Foo type

variable, anotherFoo, and assign it to the

same object. There are now two identical references

:

myFoo and anotherFoo, but only one actual Foo object instance. If we change things in the state of the

Foo object itself, we see the same effect

by looking at it with either reference.

Object references are passed to methods in the same way. In this case, either

myFoo or anotherFoo would serve as equivalent arguments:

myMethod( myFoo );

An important, but sometimes confusing, distinction to make at this point is

that the reference itself is a value and that value is copied when it is

assigned to a variable or passed in a method call. Given our previous example,

the argument passed to a method (a local variable from the method’s point of

view) is actually a third copy of the reference, in addition to myFoo and anotherFoo. The method can alter the state of the Foo object itself through that reference (calling

its methods or altering its variables), but it can’t change the caller’s notion

of the reference to myFoo. That is, the

method can’t change the caller’s myFoo to

point to a different Foo object; it can

change only its own reference. This will be more obvious when we talk about

methods later. Java differs from C++ in this respect. If you need to change a

caller’s reference to an object in Java, you need an additional level of

indirection. The caller would have to wrap the reference in another object so

that both could share the reference to it.

Reference types always point to objects, and objects are always defined by classes. However, two special kinds of reference types, arrays and interfaces, specify the type of object they point to in a slightly different way.

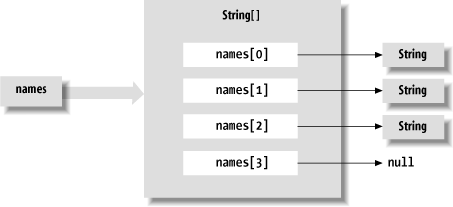

Arrays in Java have a special place in the type system. They are a special kind of object automatically created to hold a collection of some other type of object, known as the base type. Declaring an array type reference implicitly creates the new class type, as you’ll see in the next chapter.

Interfaces are a bit sneakier. An interface defines a set of methods and gives it a corresponding type. Any object that implements all methods of the interface can be treated as an object of that type. Variables and method arguments can be declared to be of interface types, just like class types, and any object that implements the interface can be assigned to them. This allows Java to cross the lines of the class hierarchy and make objects that effectively have many types. We’ll cover interfaces in the next chapter as well.

Finally, we should mention again that Java 5.0 made a major new addition to the language. Generic types or parameterized types, as they are called, are an extension of the Java class syntax that allows for additional abstraction in the way classes work with other Java types. Generics allow for specialization of classes by the user without changing any of the original class’s code. We cover generics in detail in Chapter 8.

Strings in Java are objects; they are

therefore a reference type. String objects

do, however, have some special help from the Java compiler that makes them look

more like primitive types. Literal string values in Java source code are turned

into String objects by the compiler. They can

be used directly, passed as arguments to methods, or assigned to String type variables:

System.out.println( "Hello, World..." );

String s = "I am the walrus...";

String t = "John said: \"I am the walrus...\"";The + symbol in Java is

overloaded

to provide string concatenation as well as numeric addition. Along with its

sister +=, this is the only overloaded

operator in Java:

String quote = "Four score and " + "seven years ago,";

String more = quote + " our" + " fathers" + " brought...";Java builds a single String object from the

concatenated strings

and provides it as the result of the expression. We discuss the String class and all things text-related in great

detail in Chapter 10.

Java statements appear inside methods and classes; they describe all activities of a Java program. Variable declarations and assignments, such as those in the previous section, are statements, as are basic language structures such as if/then conditionals and loops.

int size = 5;

if ( size > 10 )

doSomething();

for( int x = 0; x < size; x++ ) { ... }Expressions produce values; an expression is evaluated to produce a result, to be used as part of another expression or in a statement. Method calls, object allocations, and, of course, mathematical expressions are examples of expressions. Technically, since variable assignments can be used as values for further assignments or operations (in somewhat questionable programming style), they can be considered to be both statements and expressions.

new Object();

Math.sin( 3.1415 );

42 * 64;One of the tenets of Java is to keep things simple and consistent. To that end, when there are no other constraints, evaluations and initializations in Java always occur in the order in which they appear in the code—from left to right, top to bottom. We’ll see this rule used in the evaluation of assignment expressions, method calls, and array indexes, to name a few cases. In some other languages, the order of evaluation is more complicated or even implementation-dependent. Java removes this element of danger by precisely and simply defining how the code is evaluated. This doesn’t mean you should start writing obscure and convoluted statements, however. Relying on the order of evaluation of expressions in complex ways is a bad programming habit, even when it works. It produces code that is hard to read and harder to modify.

Statements and expressions in

Java appear within a code block. A code block is

syntactically a series of statements surrounded by an open curly brace ({) and a close curly brace (}). The statements in a code block can include

variable declarations and most of the other sorts of statements and expressions

we mentioned earlier:

{

int size = 5;

setName("Max");

...

}Methods, which look like C functions, are in a sense just code blocks that

take parameters and can be called by their names—for example, the method

setUpDog():

setUpDog( String name ) {

int size = 5;

setName( name );

...

}Variable declarations are limited in scope to their enclosing code block. That is, they can’t be seen outside of the nearest set of braces:

{

int i = 5;

}

i = 6; // Compile-time error, no such variable iIn this way, code blocks can be used to arbitrarily group other statements and variables. The most common use of code blocks, however, is to define a group of statements for use in a conditional or iterative statement.

Since a code block is itself

collectively treated as a statement, we define a conditional like an

if/else clause as

follows:

if (condition)statement; [ elsestatement; ]

So,

the if clause has the familiar (to C/C++

programmers) functionality of taking two different forms: a “one-liner” and

a block. Here’s

one:

if (condition)statement;

Here’s the other:

if (condition) { [statement; ] [statement; ] [ ... ] }

The

condition is a Boolean expression. A Boolean

expression is a true or false value or an expression that evaluates to

one of those. For example i == 0 is a

Boolean expression that tests whether the integer i holds the value 0.

In the second form, the statement is a code block,

and all its enclosed statements are executed if the conditional succeeds.

Any variables declared within that block are visible only to the statements

within the successful branch of the condition. Like the if/else conditional, most of the remaining

Java statements are concerned with controlling the flow of execution. They

act for the most part like their namesakes in other

languages.

The

do and while iterative statements have the familiar functionality;

their conditional test is also a Boolean expression:

while (condition)statement; dostatement; while (condition);

For example:

while( queue.isEmpty() )

wait();Unlike while or for

loops (which we’ll see next), that test their conditions first, a do-while loop always executes its statement

body at least once.

The most general form of the for loop is also a holdover from the C

language:

for (initialization;condition;incrementor)statement;

The

variable initialization section can declare or initialize variables that are

limited to the scope of the for

statement. The for loop then begins a

possible series of rounds in which the condition is first checked and, if

true, the body is executed. Following each execution of the body, the

incrementor expressions are evaluated to give them a chance to update

variables before the next round

begins:

for ( int i = 0; i < 100; i++ ) {

System.out.println( i );

int j = i;

...

}This

loop will execute 100 times, printing values from 0 to 99. If the condition

of a for loop returns false on the first

check, the body and incrementor section will never be

executed.

You can use multiple comma-separated expressions in

the initialization and incrementation sections of the for loop. For

example:

for (int i = 0, j = 10; i < j; i++, j-- ) {

...

}You

can also initialize existing variables from outside the scope of the

for loop within the initializer

block. You might do this if you wanted to use the end value of the loop

variable

elsewhere:

int x;

for( x = 0; hasMoreValue(); x++ )

getNextValue();

System.out.println( x );Java 5.0 introduced a new form of the

for loop (auspiciously dubbed the

“enhanced for loop”). In this simpler

form, the for loop acts like a “foreach”

statement in some other languages, iterating over a series of values in an

array or other type of collection:

for (varDeclaration:iterable)statement;

The enhanced for loop can be used to

loop over arrays of any type as well as any kind of Java object that

implements the java.lang.Iterable

interface. This includes most of the classes of the Java Collections API.

We’ll talk about arrays in this and the next chapter; Chapter 11 covers Java Collections.

Here are a couple of examples:

int [] arrayOfInts = new int [] { 1, 2, 3, 4 };

for( int i : arrayOfInts )

System.out.println( i );

List<String> list = new ArrayList<String>();

list.add("foo");

list.add("bar");

for( String s : list )

System.out.println( s );Again, we haven’t discussed arrays or the List class and special syntax in this example. What we’re

showing here is the enhanced for loop

iterating over an array of integers and also a list of string values. In the

second case, the List implements the

Iterable interface and so can be a

target of the for loop.

The

most common form of the Java switch

statement takes an integer-type argument (or an argument that can be

automatically promoted to an integer type) and selects among a number of

alternative, integer constant case

branches:

switch ( intexpression) { case intconstantExpression:statement; [ case intconstantExpression :statement; ] ... [ default :statement; ] }

The

case expression for each branch must evaluate to a different constant

integer value at compile time. An optional default case can be specified to catch unmatched conditions.

When executed, the switch simply finds the branch matching its conditional

expression (or the default branch) and executes the corresponding statement.

But that’s not the end of the story. Perhaps counterintuitively, the

switch statement then continues

executing branches after the matched branch until it hits the end of the

switch or a special statement called break. Here are a couple of

examples:

int value = 2;

switch( value ) {

case 1:

System.out.println( 1 );

case 2:

System.out.println( 2 );

case 3:

System.out.println( 3 );

}

// prints 2, 3Using

break

to terminate each branch is more

common:

int retValue = checkStatus();

switch ( retVal )

{

case MyClass.GOOD :

// something good

break;

case MyClass.BAD :

// something bad

break;

default :

// neither one

break;

}In

this example, only one branch: GOOD,

BAD, or the default is executed. The

“fall through” behavior of the switch is justified when you want to cover

several possible case values with the same statement, without resorting to a

bunch of if-else

statements:

int value = getSize();

switch( value ) {

case MINISCULE:

case TEENYWEENIE:

case SMALL:

System.out.println("Small" );

break;

case MEDIUM:

System.out.println("Medium" );

break;

case LARGE:

case EXTRALARGE:

System.out.println("Large" );

break;

}This example effectively groups the six possible values into three cases.

Enumerations and switch statements. Java 5.0 introduced enumerations to the language. Enumerations are intended to replace much of the usage of integer constants for situations like the one just discussed with a type-safe alternative. Enumerations use objects as their values instead of integers but preserve the notion of ordering and comparability. We’ll see in Chapter 5 that enumerations are declared much like classes and that the values can be “imported” into the code of your application to be used just like constants. For example:

enum Size { Small, Medium, Large }You can use enumerations in switches in Java 5.0 in the same way that the previous switch examples used integer constants. In fact, it is much safer to do so because the enumerations have real types and the compiler does not let you mistakenly add cases that do not match any value or mix values from different enumerations.

// usage

Size size = ...;

switch ( size ) {

case Small:

...

case Medium:

...

case Large:

...

}Chapter 5 provides more details about enumerations as objects.

The Java break statement and its friend continue can also be used to cut short a loop or conditional

statement by jumping out of it. A break

causes Java to stop the current block statement and resume execution after

it. In the following example, the while

loop goes on endlessly until the condition() method returns true, then it stops and proceeds

at the point marked “after

while.”

while( true ) {

if ( condition() )

break;

}

// after whileA

continue statement causes for and while loops to move on to their next iteration by returning

to the point where they check their condition. The following example prints

the numbers 0 through 99, skipping number

33.

for( int i=0; i < 100; i++ ) {

if ( i == 33 )

continue;

System.out.println( i );

}The break and continue statements should be familiar to C programmers, but Java’s have the additional ability to take a label as an argument and jump out multiple levels to the scope of the labeled point in the code. This usage is not very common in day-to-day Java coding but may be important in special cases. Here is an outline:

labelOne:

while ( condition ) {

...

labelTwo:

while ( condition ) {

...

// break or continue point

}

// after labelTwo

}

// after labelOneEnclosing

statements,

such as code blocks, conditionals, and loops, can be labeled with

identifiers like labelOne and labelTwo. In this example, a break or continue without argument at the indicated position has the

same effect as the earlier examples. A break causes processing to resume at the point labeled “after

labelTwo”; a continue immediately causes

the labelTwo loop to return to its

condition test.

The statement break

labelTwo at the indicated point has the same effect as an

ordinary break, but break labelOne breaks both levels and resumes

at the point labeled “after labelOne.” Similarly, continue labelTwo serves as a normal continue, but continue

labelOne returns to the test of the labelOne loop. Multilevel break and continue

statements remove the main justification for the evil goto statement in C/C++.

There are

a few Java statements we aren’t going to discuss right now. The try

,

catch, and finally statements are used in exception handling, as we’ll

discuss later in this chapter. The synchronized

statement in Java is used to coordinate access to statements among multiple

threads of execution; see Chapter 9

for a discussion of thread synchronization.

On a final note, we should mention that the Java compiler flags “unreachable" statements as compile-time errors. An unreachable statement is one that the compiler determines won’t be called at all. Of course, many methods may never actually be called in your code, but the compiler detects only those that it can “prove” are never called by simple checking at compile time. For example, a method with an unconditional return statement in the middle of it causes a compile-time error, as does a method with a conditional that the compiler can tell will never be fulfilled:

if (1 < 2)

return;

// unreachable statementsAn expression produces a result, or value, when it is evaluated. The value of

an expression can be a numeric type, as in an arithmetic expression; a reference

type, as in an object allocation; or the special type, void, which is the declared type of a method that doesn’t return

a value. In the last case, the expression is evaluated only for its

side effects, that is, the work it does aside from

producing a value. The type of an expression is known at compile time. The value

produced at runtime is either of this type or, in the case of a reference type,

a compatible (assignable) subtype.

Java supports almost all standard C operators. These operators also have the same precedence in Java as they do in C, as shown in Table 4-3.

Table 4-3. Java operators

|

Precedence |

Operator |

Operand type |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Arithmetic |

Increment and decrement | |

|

1 |

+, - |

Arithmetic |

Unary plus and minus |

|

1 |

~ |

Integral |

Bitwise complement |

|

1 |

! |

Boolean |

Logical complement |

|

1 |

|

Any |

Cast |

|

2 |

*, /, % |

Arithmetic |

Multiplication, division, remainder |

|

3 |

+, - |

Arithmetic |

Addition and subtraction |

|

3 |

+ |

String |

String concatenation |

|

4 |

<< |

Integral |

Left shift |

|

4 |

>> |

Integral |

Right shift with sign extension |

|

4 |

>>> |

Integral |

Right shift with no extension |

|

5 |

<, <=, >, >= |

Arithmetic |

Numeric comparison |

|

5 |

Object |

Type comparison | |

|

6 |

==, != |

Primitive |

Equality and inequality of value |

|

6 |

==, != |

Object |

Equality and inequality of reference |

|

7 |

& |

Integral |

Bitwise AND |

|

7 |

& |

Boolean |

Boolean AND |

|

8 |

^ |

Integral |

Bitwise XOR |

|

8 |

^ |

Boolean |

Boolean XOR |

|

9 |

| |

Integral |

Bitwise OR |

|

9 |

| |

Boolean |

Boolean OR |

|

10 |

&& |

Boolean |

Conditional AND |

|

11 |

|| |

Boolean |

Conditional OR |

|

12 |

?: |

N/A |

Conditional ternary operator |

|

13 |

= |

Any |

Assignment |

We should also note that the percent (%) operator is not strictly a modulo, but a remainder, and

can have a negative value.

Java also adds some new operators. As

we’ve seen, the + operator can be used

with String values to perform string

concatenation. Because all integral types in Java are signed values, the

>> operator performs a

right-arithmetic-shift operation with sign extension. The >>> operator treats the operand as an

unsigned number and performs a right-arithmetic-shift with no sign

extension. The new operator, as in C++,

is used to create objects; we will discuss it in detail

shortly.

While variable initialization (i.e., declaration and assignment together) is considered a statement, with no resulting value, variable assignment alone is an expression:

int i, j; // statement

i = 5; // both expression and statementNormally, we rely on assignment for its side effects alone, but, as in C, an assignment can be used as a value in another part of an expression:

j = ( i = 5 );

Again, relying on order of evaluation extensively (in this case, using compound assignments in complex expressions) can make code obscure and hard to read. Do so at your own peril.

The expression null can be assigned to

any reference type. It means “no reference.” A null reference can’t be used to reference anything and

attempting to do so generates a NullPointerException at runtime.

The

dot (.) operator is used to select

members of a class or object instance. It can retrieve the value of an

instance variable (of an object) or a static variable (of a class). It can

also specify a method to be invoked on an object or class:

int i = myObject.length;

String s = myObject.name;

myObject.someMethod();A reference-type expression can be used in compound evaluations by selecting further variables or methods on the result:

int len = myObject.name.length();

int initialLen = myObject.name.substring(5, 10).length();Here we have found the length of our name variable by invoking the length() method of the String object. In the second case, we took an intermediate

step and asked for a substring of the name string. The substring

method of the String class also returns a

String reference, for which we ask

the length. Compounding operations like this is also called

chaining

method calls, which we’ll mention later. One chained

selection operation that we’ve used a lot already is calling the println() method on the variable out of the System class:

System.out.println("calling println on out");Methods are functions that live within a class and may be accessible through the class or its instances, depending on the kind of method. Invoking a method means to execute its body, passing in any required parameter variables and possibly getting a value in return. A method invocation is an expression that results in a value. The value’s type is the return type of the method:

System.out.println( "Hello, World..." );

int myLength = myString.length();Here, we invoked the methods println()

and length() on different

objects.

The length() method returned an integer

value; the return type of println() is

void.

This is all pretty simple, but in Chapter 5 we’ll see that it gets a little more complex when there are methods with the same name but different parameter types in the same class or when a method is redefined in a child class, as described in Chapter 6.

Objects in Java are allocated with the

new

operator:

Object o = new Object();

The

argument to new is the constructor for

the class. The constructor is a method that always has

the same name as the class. The constructor specifies any required

parameters to create an instance of the object. The value of the new expression is a reference of the type of

the created object. Objects always have one or more constructors, though they may not

always be accessible to you.

We look at object

creation in detail in Chapter 5. For now, just note that

object creation is a type of expression and that the result is an object

reference. A minor oddity is that the binding of new is “tighter” than that of the dot (.) selector. So you can create a new object

and invoke a method in it without assigning the object to a reference type

variable if you have some reason

to:

int hours = new Date().getHours();

The

Date class is a utility class that

represents the current time. Here we create a new instance of Date with the new operator and call its getHours() method to retrieve the current hour as an integer

value. The Date object reference lives

long enough to service the method call and is then cut loose and

garbage-collected at some point in the future (see Chapter 5 for details about garbage

collection).

Calling methods in object references in this way

is, again, a matter of style. It would certainly be clearer to allocate an

intermediate variable of type Date to

hold the new object and then call its getHours() method. However, combining operations like this is

common.

The instanceof

operator can be used to determine the type of an object at runtime. It tests

to see if an object is of the same type or a subtype of the target type.

This is the same as asking if the object can be assigned to a variable of

the target type. The target type may be a class, interface, or array type as

we’ll see later. instanceof returns a

boolean value that indicates whether

the object matches the type:

Boolean b;

String str = "foo";

b = ( str instanceof String ); // true, str is a String

b = ( str instanceof Object ); // also true, a String is an Object

//b = ( str instanceof Date ); // The compiler is smart enough to catch this!instanceof also correctly reports

whether the object is of the type of an array or a specified interface (as

we’ll discuss later):

if ( foo instanceof byte[] )

...It is also important to note that the value null is not considered an instance of any object. The

following test returns false, no matter

what the declared type of the variable:

String s = null;

if ( s instanceof String )

// false, null isn't an instance of anythingJava has its roots in embedded systems—software that runs inside specialized devices, such as hand-held computers, cellular phones, and fancy toasters. In those kinds of applications, it’s especially important that software errors be handled robustly. Most users would agree that it’s unacceptable for their phone to simply crash or for their toast (and perhaps their house) to burn because their software failed. Given that we can’t eliminate the possibility of software errors, it’s a step in the right direction to recognize and deal with anticipated application-level errors methodically.

Dealing with errors in a language such as C is entirely the responsibility of the

programmer. The language itself provides no help in identifying error types and no

tools for dealing with them easily. In C, a routine generally indicates a failure by

returning an “unreasonable” value (e.g., the idiomatic -1 or null). As the programmer,

you must know what constitutes a bad result and what it means. It’s often awkward to

work around the limitations of passing error values in the normal path of data flow.

[*] An even worse problem is that certain types of errors can legitimately

occur almost anywhere, and it’s prohibitive and unreasonable to explicitly test for

them at every point in the software.

Java offers an elegant solution to these problems through

exceptions

.

(Java exception handling is similar to, but not quite the same as, exception

handling in C++.) An exception indicates an unusual condition

or an error condition. Program control becomes unconditionally transferred or

“thrown” to a specially designated section of code where it’s caught and handled. In

this way, error handling is orthogonal to (or independent of) the normal flow of the

program. We don’t have to have special return values for all our methods; errors are

handled by a separate mechanism. Control can be passed a long distance from a deeply

nested routine and handled in a single location when that is desirable, or an error

can be handled immediately at its source. A few standard methods return -1 as a special value, but these are generally limited

to situations where we are expecting a special value and the situation is not really

out of bounds.[*]

A Java method is required to specify the exceptions it can throw (i.e., the ones that it doesn’t catch itself), and the compiler makes sure that users of the method handle them. In this way, the information about what errors a method can produce is promoted to the same level of importance as its argument and return types. You may still decide to punt and ignore obvious errors, but in Java you must do so explicitly.

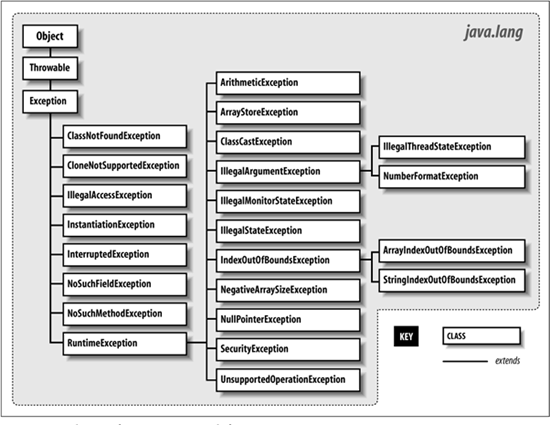

Exceptions are represented by instances of the

class java.lang.Exception and its subclasses.

Subclasses of Exception can hold specialized

information (and possibly behavior) for different kinds of exceptional

conditions. However, more often they are simply “logical” subclasses that serve

only to identify a new exception type. Figure 4-1 shows the subclasses of Exception in the java.lang

package. It should give you a feel for how exceptions are organized. Most other

packages define their own exception types, which usually are subclasses of

Exception itself or of its important

subclass RuntimeException

,

which we’ll discuss in a moment.

For example, an important exception class is IOException

in the package java.io. The IOException class extends Exception and has many subclasses for typical I/O problems (such

as a FileNotFoundException) and networking

problems (such as a MalformedURLException).

Network exceptions belong to the java.net

package. Another important descendant of IOException is RemoteException

,

which belongs to the java.rmi package. It is

used when problems arise during remote method

invocation (RMI). Throughout this book, we mention exceptions you need to be aware of as we encounter them.

An Exception object is created by the code

at the point where the error condition arises. It can be designed to hold

whatever information is necessary to describe the exceptional condition and also

includes a full stack trace for debugging. (A stack trace

is the list of all the methods called in order to reach the point where the

exception was thrown.) The Exception object

is passed as an argument to the handling block of code, along with the flow of

control. This is where the terms “throw” and “catch” come from: the Exception object is thrown from one point in the

code and caught by the other, where execution resumes.

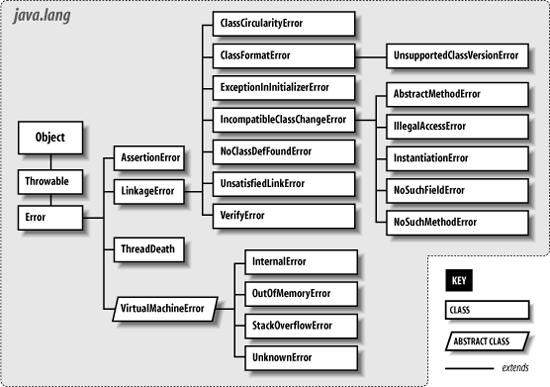

The Java API also defines the java.lang.Error class for unrecoverable errors. The subclasses of

Error in the java.lang package are shown in Figure 4-2. A notable Error type is AssertionError, which is used by the assert statement to indicate

a failure (assertions are discussed later in this chapter). A few other packages

define their own subclasses of Error, but

subclasses of Error are much less common (and

less useful) than subclasses of Exception.

You generally needn’t worry about these errors in your code (i.e., you do not

have to catch them); they are intended to indicate fatal problems or virtual

machine errors. An error of this kind usually causes the Java interpreter to

display a message and exit. You are actively discouraged from trying to

catch

or recover from them because they are supposed to indicate a fatal program bug,

not a routine condition.

Both Exception and Error are subclasses of Throwable. The Throwable class

is the base class for objects which can be “thrown” with the throw statement. In general, you should extend

only Exception, Error, or one of their subclasses.

The try/catch

guarding statements wrap a block of code and catch designated types of

exceptions that occur within it:

try {

readFromFile("foo");

...

}

catch ( Exception e ) {

// Handle error

System.out.println( "Exception while reading file: " + e );

...

}In this example, exceptions that occur within the body of the try portion of the statement are directed to the

catch clause for possible handling. The

catch clause acts like a method; it

specifies as an argument the type of exception it wants to handle and, if it’s

invoked, it receives the Exception

object as an argument. Here, we receive the object in the variable e and print it along with a message.

A try statement can have multiple catch clauses that specify different types

(subclasses) of Exception:

try {

readFromFile("foo");

...

}

catch ( FileNotFoundException e ) {

// Handle file not found

...

}

catch ( IOException e ) {

// Handle read error

...

}

catch ( Exception e ) {

// Handle all other errors

...

}The catch clauses are evaluated in order,

and the first assignable match is taken. At most, one catch clause is executed, which means that the exceptions should

be listed from most to least specific. In the previous example, we anticipate

that the hypothetical readFromFile() can

throw two different kinds of exceptions: one for a file not found and another

for a more general read error. Any subclass of Exception is assignable to the parent type Exception, so the third catch clause acts like the default clause in a switch

statement and handles any remaining possibilities. We’ve shown it here for

completeness, but in general you want to be as specific as possible in the

exception types you catch.

One beauty of the try/catch scheme is that

any statement in the try block can assume

that all previous statements in the block succeeded. A problem won’t arise

suddenly because a programmer forgot to check the return value from some method.

If an earlier statement fails, execution jumps immediately to the catch clause; later statements are never

executed.

What if we hadn’t caught the

exception? Where would it have gone? Well, if there is no enclosing try/catch statement, the exception pops to the top

of the method in which it appeared and is, in turn, thrown from that method up

to its caller. If that point in the calling method is within a try clause, control passes to the corresponding

catch clause. Otherwise, the exception

continues propagating up the call stack, from one method to its caller. In this

way, the exception bubbles up until it’s caught, or until it pops out of the top

of the program, terminating it with a runtime error message. There’s a bit more

to it than that because, in this case, the compiler might have reminded us to

deal with it, but we’ll get back to that in a moment.

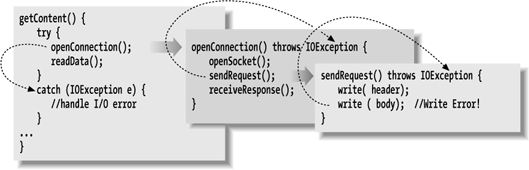

Let’s look at another example. In Figure 4-3, the method getContent() invokes the method openConnection() from within a try/catch statement. In turn, openConnection() invokes the method sendRequest(), which calls the method write() to send some data.

In this figure, the second call to write()

throws an IOException. Since sendRequest() doesn’t contain a try/catch statement to handle the exception, it’s

thrown again from the point where it was called in the method openConnection(). Since openConnection() doesn’t catch the exception either, it’s thrown

once more. Finally, it’s caught by the try

statement in getContent() and handled by its

catch clause.

Since an exception can bubble up quite a distance

before it is caught and handled, we may need a way to determine exactly where it

was thrown. It’s also very important to know the context of how the point of the

exception was reached; that is, which methods called which methods to get to

that point. All exceptions can dump a stack trace that lists their method of

origin and all the nested method calls it took to arrive there. Most commonly,

the user sees a stack trace when it is printed using the printStackTrace()

method.

try {

// complex, deeply nested task

} catch ( Exception e ) {

// dump information about exactly where the exception occurred

e.printStackTrace( System.err );

...

}For example, the stack trace for an exception might look like this:

java.io.FileNotFoundException: myfile.xml

at java.io.FileInputStream.<init>(FileInputStream.java)

at java.io.FileInputStream.<init>(FileInputStream.java)

at MyApplication.loadFile(MyApplication.java:137)

at MyApplication.main(MyApplication.java:5)This stack trace indicates that the main()

method of the class MyApplication called the

method loadFile(). The loadFile() method then tried to construct a

FileInputStream, which threw the FileNotFoundException. Note that once the stack

trace reaches Java system classes (like FileInputStream), the line numbers may be lost. This can also

happen when the code is optimized by some virtual machines. Usually, there is a

way to disable the optimization temporarily to find the exact line numbers.

However, in tricky situations, changing the timing of the application can affect

the problem you’re trying to debug.

Prior to Java 1.4, stack traces were limited to a text output that was really

suitable for printing and reading only by humans. Now methods allow you to

retrieve the stack trace information programmatically, using the Throwable

getStackTrace() method. This method returns an array of StackTraceElement objects, each of which

represents a method call on the stack. You can ask a StackTraceElement for details about that method’s location using

the methods getFileName(), getClassName(), getMethodName(), and getLineNumber(). Element zero of the array is the top of the

stack, the final line of code that caused the exception; subsequent elements

step back one method call each until the original main() method is reached.

We mentioned earlier

that Java forces us to be explicit about our error handling, but it’s not

realistic to require that every conceivable type of error be handled in every

situation. Java exceptions are therefore divided into two categories:

checked

and unchecked

.

Most application-level exceptions are checked, which means that any method

that throws one, either by generating it itself (as we’ll discuss later) or by

ignoring one that occurs within it, must declare that it can throw that type of

exception in a special throws clause in its

method declaration. We haven’t yet talked in detail about declaring

methods (see Chapter 5). For now all you

need to know is that methods have to declare the checked exceptions they can throw or allow to be

thrown.

Again in Figure 4-3, notice that

the methods openConnection() and sendRequest() both specify that they can throw an

IOException. If we had to throw multiple

types of exceptions, we could declare them separated with commas:

void readFile( String s ) throws IOException, InterruptedException {

...

}The throws clause tells the compiler that a

method is a possible source of that type of checked exception and that anyone

calling that method must be prepared to deal with it. The caller may use a

try/catch block to catch it, or, in turn,

it may declare that it can throw the exception itself.

In contrast, exceptions that are subclasses of either the class java.lang. RuntimeException or the class java.lang.Error are unchecked. See Figure 4-1 for the subclasses of

RuntimeException. (Subclasses of Error are generally reserved for serious class

loading or runtime

system problems.) It’s not a compile-time error to ignore the possibility of

these exceptions; methods also don’t have to declare they can throw them. In all

other respects, unchecked exceptions behave the same as other exceptions. We are

free to catch them if we wish, but in this case we aren’t required to.

Checked exceptions are intended to cover application-level problems, such as

missing files and unavailable hosts. As good programmers (and upstanding

citizens), we should design software to recover gracefully from these kinds of

conditions. Unchecked exceptions are intended for system-level problems, such as

“out of memory” and “array index out of bounds.” While these may indicate

application-level programming errors, they can occur almost anywhere and usually

aren’t possible to recover from. Fortunately, because they are unchecked

exceptions, you don’t have to wrap every one of your array-index operations in a

try/catch statement.

To sum up, checked exceptions are problems a reasonable application should try to handle gracefully; unchecked exceptions (runtime exceptions or errors) are problems from which we would not normally expect our software to recover. Error types are those explicitly intended to be conditions that we should not normally try to handle or recover from.

We can throw our own exceptions, either

instances of Exception, one of its existing

subclasses, or our own specialized exception classes. All we have to do is

create an instance of the Exception and throw

it with the throw statement:

throw new IOException();

Execution stops and is transferred to the nearest enclosing try/catch statement that can handle the exception

type. (There is little point in keeping a reference to the Exception object we’ve created here.) An

alternative constructor lets us specify a string with an error message:

throw new IOException("Sunspots!");You can retrieve this string by using the Exception object’s getMessage()

method. Often, though, you can just print (or toString()) the exception object itself to get the message and

stack trace.

By convention, all types of Exception have

a String constructor like this. The earlier

String message is somewhat facetious and

vague. Normally, you won’t throw a plain old Exception but a more specific subclass. Here’s another

example:

public void checkRead( String s ) {

if ( new File(s).isAbsolute() || (s.indexOf("..") != -1) )

throw new SecurityException(

"Access to file : "+ s +" denied.");

}In this code, we partially implement a method to check for an illegal path. If

we find one, we throw a SecurityException,

with some information about the transgression.

Of course, we could include whatever other information is useful in our own

specialized subclasses of Exception. Often,

though, just having a new type of exception is good enough because it’s

sufficient to help direct the flow of control. For example, if we are building a

parser, we might want to make our own kind of exception to indicate a particular

kind of failure:

class ParseException extends Exception { ParseException() { super(); } ParseException( String desc ) { super( desc ); } }

See Chapter 5 for a full description

of classes and class constructors. The body of our Exception class here simply allows a ParseException to be created in the conventional ways we’ve

created exceptions

previously (either generically or with a simple string description). Now that we

have our new exception type, we can guard like this:

// Somewhere in our code

...

try {

parseStream( input );

} catch ( ParseException pe ) {

// Bad input...

} catch ( IOException ioe ) {

// Low-level communications problem

}As you can see, although our new exception doesn’t currently hold any specialized information about the problem (it certainly could), it does let us distinguish a parse error from an arbitrary I/O error in the same chunk of code.

Sometimes you’ll want to take some

action based on an exception and then turn around and throw a new exception

in its place. This is common when building frameworks, where low-level

detailed exceptions are handled and represented by higher-level exceptions

that can be managed more easily. For example, you might want to catch an

IOException in a communication

package, possibly perform some cleanup, and ultimately throw a higher-level

exception of your own, maybe something like LostServerConnection.

You can do this in the

obvious way by simply catching the exception and then throwing a new one,

but then you lose important information, including the stack trace of the

original “causal” exception. To deal with this, you can use the technique of

exception chaining. This means that you include the

causal exception in the new exception that you throw. Java has explicit

support for exception chaining. The base Exception class can be constructed with an exception as an

argument or the standard String message

and an

exception:

throw new Exception( "Here's the story...", causalException );

You

can get access to the wrapped exception later with the getCause()

method. More importantly, Java automatically prints both exceptions and

their respective stack traces if you print the exception or if it is shown

to the user.

You can add this kind of constructor to your own

exception subclasses (delegating to the parent constructor). However, since

this API is a recent addition to Java (added in Version 1.4), many existing

exception types do not provide this kind of constructor. You can still take

advantage of this pattern by using the Throwable method initCause() to set the causal exception explicitly after

constructing your exception and before throwing

it:

try {

// ...

} catch ( IOException cause ) {

Exception e =

new IOException("What we have here is a failure to communicate...");

e.initCause( cause );

throw e;

}The try

statement imposes a condition on the statements that it guards. It says that if

an exception occurs within it, the remaining statements are abandoned. This has

consequences for local variable initialization. If the compiler can’t determine

whether a local variable assignment placed inside a try/catch

block will happen, it won’t let us use the variable. For example:

void myMethod() {

int foo;

try {

foo = getResults();

}

catch ( Exception e ) {

...

}

int bar = foo; // Compile-time error -- foo may not have been initializedIn this example, we can’t use foo in the

indicated place because there’s a chance it was never assigned a value. One

obvious option is to move the assignment inside the try statement:

try {

foo = getResults();

int bar = foo; // Okay because we get here only

// if previous assignment succeeds

}

catch ( Exception e ) {

...

}Sometimes this works just fine. However, now we have the same problem if we

want to use bar later in myMethod(). If we’re not careful, we might end up

pulling everything into the try statement.

The situation changes, however, if we transfer control out of the method in the

catch clause:

try {

foo = getResults();

}

catch ( Exception e ) {

...

return;

}

int bar = foo; // Okay because we get here only

// if previous assignment succeedsThe compiler is smart enough to know that if an error had occurred in the

try clause, we wouldn’t have reached the

bar assignment, so it allows us to refer

to foo. Your code will dictate its own needs;

you should just be aware of the options.

What if we have some cleanup to do before

we exit our method from one of the catch

clauses? To avoid duplicating the code in each catch branch and to make the cleanup more explicit, use the

finally clause. A finally clause can be added after a try and any associated catch clauses. Any statements in the body of the finally clause are guaranteed to be executed, no

matter how control leaves the try body

(whether an exception was thrown or not):

try {

// Do something here

}

catch ( FileNotFoundException e ) {

...

}

catch ( IOException e ) {

...

}

catch ( Exception e ) {

...

}

finally {

// Cleanup here is always executed

}In this example, the statements at the cleanup point are executed eventually,

no matter how control leaves the try. If

control transfers to one of the catch

clauses, the statements in finally are

executed after the catch completes. If none

of the catch clauses handles the exception,

the finally statements are executed before

the exception propagates to the next level.

If the statements in the try execute

cleanly, or if we perform a return

,

break, or continue, the statements in the finally clause are still executed. To perform cleanup operations,

we can even use try and finally without any catch clauses:

try {

// Do something here

return;

}

finally {

System.out.println("Whoo-hoo!");

}Exceptions that occur in a catch or

finally clause are handled normally; the

search for an enclosing try/catch begins

outside the offending try statement, after

the finally has been executed.

Because of the way the Java virtual machine is

implemented, guarding against an exception being thrown (using a try) is free. It doesn’t add any overhead to the

execution of your code. However, throwing an exception is not free. When an

exception is thrown, Java has to locate the appropriate try/catch block and perform other time-consuming activities at

runtime.

The result is that you should throw exceptions only in truly “exceptional” circumstances and avoid using them for expected conditions, especially when performance is an issue. For example, if you have a loop, it may be better to perform a small test on each pass and avoid throwing the exception rather than throwing it frequently. On the other hand, if the exception is thrown only once in a gazillion times, you may want to eliminate the overhead of the test code and not worry about the cost of throwing that exception. The general rule should be that exceptions are used for “out of bounds” or abnormal situations, not routine and expected conditions (such as the end of a file).

An assertion is a simple pass/fail test of some condition, performed while your application is running. Assertions can be used to “sanity” check your code anywhere you believe certain conditions are guaranteed by correct program behavior. Assertions are distinct from other kinds of tests because they check conditions that should never be violated at a logical level: if the assertion fails, the application is to be considered broken and generally halts with an appropriate error message. Assertions are supported directly by the Java language and they can be turned on or off at runtime to remove any performance penalty of including them in your code.

Using assertions to test for the correct behavior of your application is a simple but powerful technique for ensuring software quality. It fills a gap between those aspects of software that can be checked automatically by the compiler and those more generally checked by “unit tests” and human testing. Assertions test assumptions about program behavior and make them guarantees (at least while they are activated).

Explicit support for assertions was added in Java 1.4. However, if you’ve written much code in any language, you have probably used assertions in some form. For example, you may have written something like the following:

if ( !condition )

throw new AssertionError("fatal error: 42");An assertion in Java is equivalent to this example but performed with the assert

language keyword. It takes a Boolean condition and an optional expression value. If

the assertion fails, an AssertionError is thrown,

which usually causes Java to bail out of the application.

The optional expression may evaluate to either a primitive or object type. Either way, its sole purpose is to be turned into a string and shown to the user if the assertion fails; most often you’ll use a string message explicitly. Here are some examples:

assert false;

assert ( array.length > min );

assert a > 0 : a // shows value of a to the user

assert foo != null : "foo is null!" // shows message to userIn the event of failure, the first two assertions print only a generic message,

whereas the third prints the value of a and the

last prints the foo is null! message.

Again, the important thing about assertions is not just that they are more terse

than the equivalent if condition but that they

can be enabled or disabled when you run the application. Disabling assertions means

that their test conditions are not even evaluated, so there is no performance

penalty for including them in your code (other than, perhaps, space in the class

files when they are loaded).

Java 5.0 supports assertions natively. In Java 1.4 (the previous version in this crazy numbering scheme), code with assertions requires a compile-time switch:

% javac -source 1.4 MyApplication.javaAssertions

are turned on or off at runtime. When disabled, assertions still exist in the

class files but are not executed and consume no time. You can enable and disable

assertions for an entire application or on a package-by-package or even

class-by-class basis. By default, assertions are turned off in Java. To enable

them for your code, use the java command flag

-ea or -enableassertions:

% java -ea MyApplicationTo turn on assertions for a particular class, append the class name:

% java -ea:com.oreilly.examples.Myclass MyApplicationTo turn on assertions just for particular packages, append the package name with trailing ellipses (. . .):

%java -ea:com.oreilly.examples...MyApplication

When you enable assertions for a package, Java also enables all subordinate

package names (e.g., com.oreilly.examples.text). However, you can be more selective by

using the corresponding -da or -disableassertions flag to negate individual

packages or classes. You can combine all this to achieve arbitrary groupings

like this:

%java -ea:com.oreilly.examples... -da:com.oreilly.examples.text-ea:com.oreilly.examples.text.MonkeyTypewriters MyApplication

This example enables assertions for the com.oreilly.examples package as a whole, excludes the package

com.oreilly.examples.text, then turns

exceptions on for just one class, MonkeyTypewriters, in that package.

An assertion enforces a rule about something that should be unchanging in your code and would otherwise go unchecked. You can use an assertion for added safety anywhere you want to verify your assumptions about program behavior that can’t be checked by the compiler.

A common situation that cries out for an assertion is testing for multiple

conditions or values where one should always be found. In this case, a failing

assertion as the default or “fall through” behavior indicates the code is

broken. For example, suppose we have a value called direction that should always contain either the constant value

LEFT or RIGHT:

if ( direction == LEFT )

doLeft();

else if ( direction == RIGHT )

doRight()

else

assert false : "bad direction";The same applies to the default case of a switch:

switch ( direction ) {

case LEFT:

doLeft();

break;

case RIGHT:

doRight();

break;

default:

assert false;

}In general, you should not use assertions for checking the validity of arguments to methods because you want that behavior to be part of your application, not just a test for quality control that can be turned off. The validity of input to a method is called its preconditions, and you should usually throw an exception if they are not met; this elevates the preconditions to part of the method’s “contract” with the user. However, checking the correctness of results of your methods with assertions before returning them is a good idea; these are called post-conditions.

Sometimes determining what is or is not a precondition depends on your point of view. For example, when a method is used internally within a class, preconditions may already be guaranteed by the methods that call it. Public methods of the class should probably throw exceptions when their preconditions are violated, but a private method might use assertions because its callers are always closely related code that should obey the correct behavior.

Finally, note that assertions cannot only test simple expressions but perform

complex validation as well. Remember that anything you place in the condition

expression of an assert statement is not

evaluated when assertions are turned off. You can make helper methods

for your assertions, containing arbitrary amounts of

code. And, although it suggests a dangerous programming style, you can even use

assertions that have side effects to capture values for use by later

assertions—all of which will be disabled when assertions are turned off. For

example:

int savedValue;

assert ( savedValue = getValue()) != -1;

// Do work...

assert checkValue( savedValue );Here, in the first assert, we use helper

method getValue() to retrieve some

information and save it for later. Then after doing some work, we check the

saved value using another assertion, perhaps comparing results. When assertions

are disabled, we’ll no longer save or check the data. Note that it’s necessary