The GoF refers to the Prototype pattern as one that creates objects based on a template of an existing object through cloning.

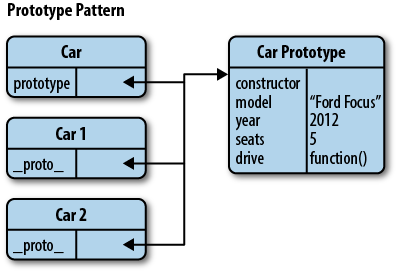

We can think of the Prototype pattern as being based on prototypal

inheritance in which we create objects that act as prototypes for other

objects. The prototype object itself is effectively

used as a blueprint for each object the constructor creates. If the

prototype of the constructor function used contains a property called

name for example (as per the code

sample that follows), then each object created by that same constructor

will also have this same property (Figure 9-6).

Reviewing the definitions for this pattern in existing (non-JavaScript) literature, we may find references to classes once again. The reality is that prototypal inheritance avoids using classes altogether. There isnât a âdefinitionâ object nor a core object in theory; weâre simply creating copies of existing functional objects.

One of the benefits of using the Prototype pattern is that weâre working with the prototypal strengths JavaScript has to offer natively rather than attempting to imitate features of other languages. With other design patterns, this isnât always the case.

Not only is the pattern an easy way to implement inheritance, but it can come with a performance boost as well: when defining functions in an object, theyâre all created by reference (so all child objects point to the same function), instead of creating their own individual copies.

For those interested, real prototypal inheritance, as defined in the

ECMAScript 5 standard, requires the use of Object.create (which we previously looked at

earlier in this section). To review, Object.create creates an object that has a

specified prototype and optionally contains specified properties as well

(e.g., Object.create( prototype,

optionalDescriptorObjects )).

We can see this demonstrated in the following example:

varmyCar={name:"Ford Escort",drive:function(){console.log("Weeee. I'm driving!");},panic:function(){console.log("Wait. How do you stop this thing?");}};// Use Object.create to instantiate a new carvaryourCar=Object.create(myCar);// Now we can see that one is a prototype of the otherconsole.log(yourCar.name);

Object.create also allows us to

easily implement advanced concepts such as differential inheritance

in which objects are able to directly inherit from other

objects. We saw earlier that Object.create allows us to initialize object

properties using the second supplied argument. For example:

varvehicle={getModel:function(){console.log("The model of this vehicle is.."+this.model);}};varcar=Object.create(vehicle,{"id":{value:MY_GLOBAL.nextId(),// writable:false, configurable:false by defaultenumerable:true},"model":{value:"Ford",enumerable:true}});

Here, the properties can be initialized on the second argument of

Object.create using an object literal

with a syntax similar to that used by the Object.defineProperties and Object.defineProperty methods that we looked at

previously.

It is worth noting that prototypal relationships can cause trouble

when enumerating properties of objects and (as Crockford recommends) wrapping the contents of the

loop in a hasOwnProperty()

check.

If we wish to implement the Prototype pattern without directly using

Object.create, we can simulate the

pattern as per the above example as follows:

varvehiclePrototype={init:function(carModel){this.model=carModel;},getModel:function(){console.log("The model of this vehicle is.."+this.model);}};functionvehicle(model){functionF(){};F.prototype=vehiclePrototype;varf=newF();f.init(model);returnf;}varcar=vehicle("Ford Escort");car.getModel();

Note

This alternative does not allow the user to define read-only

properties in the same manner (as the

vehiclePrototype may be altered if not careful).

A final alternative implementation of the Prototype pattern could be the following:

varbeget=(function(){functionF(){}returnfunction(proto){F.prototype=proto;returnnewF();};})();

One could reference this method from the vehicle function. Note, however that vehicle here is emulating a constructor, since

the Prototype pattern does not include any notion of initialization beyond

linking an object to a prototype.

Get Learning JavaScript Design Patterns now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.