Decorators are a structural design pattern that aim to promote code reuse. Similar to Mixins, they can be considered another viable alternative to object subclassing.

Classically, Decorators offered the ability to add behavior to existing classes in a system dynamically. The idea was that the decoration itself wasnât essential to the base functionality of the class; otherwise, it would be baked into the superclass itself.

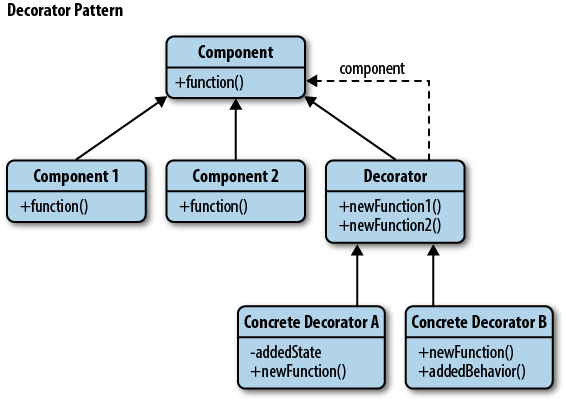

They can be used to modify existing systems where we wish to add additional features to objects without the need to heavily modify the underlying code using them. A common reason why developers use them is that their applications may contain features requiring a large quantity of distinct types of object. Imagine having to define hundreds of different object constructors for, say, a JavaScript game (Figure 9-11).

The object constructors could represent distinct player types, each

with differing capabilities. A Lord of the Rings game

could require constructors for Hobbit,

Elf, Orc, Wizard,

Mountain Giant, Stone Giant, and so on, but there could easily

be hundreds of these. If we then factored in capabilities, imagine having

to create subclasses for each

combination of capability typeâe.g., HobbitWithRing, HobbitWithSword, HobbitWithRingAndSword, and so on. This

isnât very practical and certainly isnât manageable when we factor in a

growing number of different abilities.

The Decorator pattern isnât heavily tied to how objects are created but instead focuses on the problem of extending their functionality. Rather than just relying on prototypal inheritance, we work with a single base object and progressively add decorator objects that provide the additional capabilities. The idea is that rather than subclassing, we add (decorate) properties or methods to a base object so itâs a little more streamlined.

Adding new attributes to objects in JavaScript is a very straightforward process, so with this in mind, a very simplistic decorator may be implemented as follows (Examples 9-7 and 9-8):

Example 9-7. Decorating Constructors with New Functionality

// A vehicle constructorfunctionvehicle(vehicleType){// some sane defaultsthis.vehicleType=vehicleType||"car";this.model="default";this.license="00000-000";}// Test instance for a basic vehiclevartestInstance=newvehicle("car");console.log(testInstance);// Outputs:// vehicle: car, model:default, license: 00000-000// Lets create a new instance of vehicle, to be decoratedvartruck=newvehicle("truck");// New functionality we're decorating vehicle withtruck.setModel=function(modelName){this.model=modelName;};truck.setColor=function(color){this.color=color;};// Test the value setters and value assignment works correctlytruck.setModel("CAT");truck.setColor("blue");console.log(truck);// Outputs:// vehicle:truck, model:CAT, color: blue// Demonstrate "vehicle" is still unalteredvarsecondInstance=newvehicle("car");console.log(secondInstance);// Outputs:// vehicle: car, model:default, license: 00000-000

This type of simplistic implementation is functional, but it doesnât really demonstrate all of the strengths Decorators have to offer. For this, weâre first going to go through my variation of the Coffee example from an excellent book called Head First Design Patterns by Freeman, Sierra and Bates, which is modeled around a Macbook purchase.

Example 9-8. Decorating Objects with Multiple Decorators

// The constructor to decoratefunctionMacBook(){this.cost=function(){return997;};this.screenSize=function(){return11.6;};}// Decorator 1functionMemory(macbook){varv=macbook.cost();macbook.cost=function(){returnv+75;};}// Decorator 2functionEngraving(macbook){varv=macbook.cost();macbook.cost=function(){returnv+200;};}// Decorator 3functionInsurance(macbook){varv=macbook.cost();macbook.cost=function(){returnv+250;};}varmb=newMacBook();Memory(mb);Engraving(mb);Insurance(mb);// Outputs: 1522console.log(mb.cost());// Outputs: 11.6console.log(mb.screenSize());

In the example, our Decorators are overriding the MacBook() superclass objectâs .cost() function to return the current price

of the Macbook plus the cost of the

upgrade being specified.

Itâs considered a decorationâ as the original Macbook objectsâ constructor methods that are

not overridden (e.g. screenSize()),

as well as any other properties that we may define as a part of the

Macbook, remain unchanged and

intact.

There isnât really a defined interface in the previous example, and weâre shifting away the responsibility of ensuring an object meets an interface when moving from the creator to the receiver.

Get Learning JavaScript Design Patterns now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.