The Flyweight pattern is a classical structural solution for optimizing code that is repetitive, slow, and inefficiently shares data. It aims to minimize the use of memory in an application by sharing as much data as possible with related objects (e.g., application configuration, state, and so onâsee Figure 9-12).

The pattern was first conceived by Paul Calder and Mark Linton in 1990 and was named after the boxing weight class that includes fighters weighing less than 112 lb. The name Flyweight itself is derived from this weight classification, as it refers to the small weight (memory footprint) the pattern aims to help us achieve.

In practice, Flyweight data sharing can involve taking several similar objects or data constructs used by a number of objects and placing this data into a single external object. We can pass through this object through to those depending on this data, rather than storing identical data across each one.

There are two ways in which the Flyweight pattern can be applied. The first is at the data layer, where we deal with the concept of sharing data between large quantities of similar objects stored in memory.

The second is at the DOM layer, where the Flyweight can be used as a central event-manager to avoid attaching event handlers to every child element in a parent container we wish to have some similar behavior.

As the data layer is where the Flyweight pattern is most used traditionally, weâll take a look at this first.

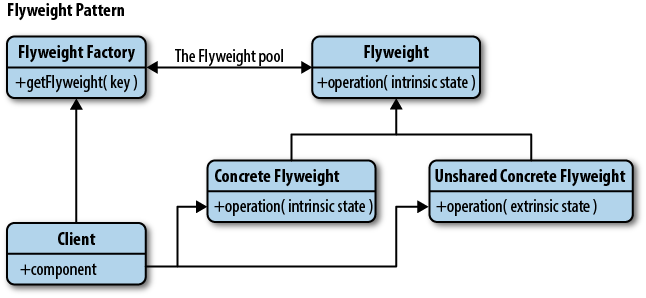

For this application, there are a few more concepts around the classical Flyweight pattern that we need to be aware of. In the Flyweight pattern, thereâs a concept of two states: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic information may be required by internal methods in our objects, which they absolutely cannot function without. Extrinsic information can however be removed and stored externally.

Objects with the same intrinsic data can be replaced with a single shared object, created by a factory method. This allows us to reduce the overall quantity of implicit data being stored quite significantly.

The benefit of this is that weâre able to keep an eye on objects that have already been instantiated so that new copies are only ever created should the intrinsic state differ from the object we already have.

We use a manager to handle the extrinsic states. How this is implemented can vary, but one approach is to have the manager object contain a central database of the extrinsic states and the flyweight objects to which they belong.

As the Flyweight pattern hasnât been heavily used in JavaScript in recent years, many of the implementations we might use for inspiration come from the Java and C++ worlds.

Our first look at Flyweights in code is my JavaScript implementation of the Java sample of the Flyweight pattern from Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flyweight_pattern).

We will be making use of three types of Flyweight components in this implementation, which are listed below:

- Flyweight

Corresponds to an interface through which flyweights are able to receive and act on extrinsic states.

- Concrete flyweight

Actually implements the Flyweight interface and stores intrinsic states. Concrete Flyweights need to be sharable and capable of manipulating a state that is extrinsic.

- Flyweight factory

Manages flyweight objects and creates them, too. It makes sure that our flyweights are shared and manages them as a group of objects that can be queried if we require individual instances. If an object has already been created in the group, it returns it. Otherwise, it adds a new object to the pool and returns it.

These correspond to the following definitions in our implementation:

CoffeeOrder: FlyweightCoffeeFlavor: Concrete flyweightCoffeeOrderContext: HelperCoffeeFlavorFactory: Flyweight factorytestFlyweight: Utilization of our flyweights

Duck punching allows us to extend the capabilities of a

language or solution without necessarily needing to modify the runtime

source. As this next solution requires the use of a Java keyword

(implements) for implementing

interfaces and isnât found in JavaScript natively, letâs first duck

punch it.

Function.prototype.implementsFor works on an

object constructor and will accept a parent class (function) or object

and either inherit from this using normal inheritance (for functions)

or virtual inheritance (for objects).

// Simulate pure virtual inheritance/"implement" keyword for JSFunction.prototype.implementsFor=function(parentClassOrObject){if(parentClassOrObject.constructor===Function){// Normal Inheritancethis.prototype=newparentClassOrObject();this.prototype.constructor=this;this.prototype.parent=parentClassOrObject.prototype;}else{// Pure Virtual Inheritancethis.prototype=parentClassOrObject;this.prototype.constructor=this;this.prototype.parent=parentClassOrObject;}returnthis;};

We can use this to patch the lack of an implements keyword by having a function

inherit an interface explicitly. Below, CoffeeFlavor implements the CoffeeOrder interface and must contain its

interface methods in order for us to assign the functionality powering

these implementations to an object.

// Flyweight objectvarCoffeeOrder={// InterfacesserveCoffee:function(context){},getFlavor:function(){}};// ConcreteFlyweight object that creates ConcreteFlyweight// Implements CoffeeOrderfunctionCoffeeFlavor(newFlavor){varflavor=newFlavor;// If an interface has been defined for a feature// implement the featureif(typeofthis.getFlavor==="function"){this.getFlavor=function(){returnflavor;};}if(typeofthis.serveCoffee==="function"){this.serveCoffee=function(context){console.log("Serving Coffee flavor "+flavor+" to table number "+context.getTable());};}}// Implement interface for CoffeeOrderCoffeeFlavor.implementsFor(CoffeeOrder);// Handle table numbers for a coffee orderfunctionCoffeeOrderContext(tableNumber){return{getTable:function(){returntableNumber;}};}// FlyweightFactory objectfunctionCoffeeFlavorFactory(){varflavors=[];return{getCoffeeFlavor:function(flavorName){varflavor=flavors[flavorName];if(flavor===undefined){flavor=newCoffeeFlavor(flavorName);flavors.push([flavorName,flavor]);}returnflavor;},getTotalCoffeeFlavorsMade:function(){returnflavors.length;}};}// Sample usage:// testFlyweight()functiontestFlyweight(){// The flavors ordered.varflavors=newCoffeeFlavor(),// The tables for the orders.tables=newCoffeeOrderContext(),// Number of orders madeordersMade=0,// The CoffeeFlavorFactory instanceflavorFactory;functiontakeOrders(flavorIn,table){flavors[ordersMade]=flavorFactory.getCoffeeFlavor(flavorIn);tables[ordersMade++]=newCoffeeOrderContext(table);}flavorFactory=newCoffeeFlavorFactory();takeOrders("Cappuccino",2);takeOrders("Cappuccino",2);takeOrders("Frappe",1);takeOrders("Frappe",1);takeOrders("Xpresso",1);takeOrders("Frappe",897);takeOrders("Cappuccino",97);takeOrders("Cappuccino",97);takeOrders("Frappe",3);takeOrders("Xpresso",3);takeOrders("Cappuccino",3);takeOrders("Xpresso",96);takeOrders("Frappe",552);takeOrders("Cappuccino",121);takeOrders("Xpresso",121);for(vari=0;i<ordersMade;++i){flavors[i].serveCoffee(tables[i]);}console.log(" ");console.log("total CoffeeFlavor objects made: "+flavorFactory.getTotalCoffeeFlavorsMade());}

Next, letâs continue our look at Flyweights by implementing a system to manage all of the books in a library. The important metadata for each book could probably be broken down as follows:

ID

Title

Author

Genre

Page count

Publisher ID

ISBN

Weâll also require the following properties to keep track of which member has checked out a particular book, the date that patron has checked it out on, as well as the expected date of return.

checkoutDatecheckoutMemberdueReturnDateavailability

Each book would thus be represented as follows, prior to any optimization using the Flyweight pattern:

varBook=function(id,title,author,genre,pageCount,publisherID,ISBN,checkoutDate,checkoutMember,dueReturnDate,availability){this.id=id;this.title=title;this.author=author;this.genre=genre;this.pageCount=pageCount;this.publisherID=publisherID;this.ISBN=ISBN;this.checkoutDate=checkoutDate;this.checkoutMember=checkoutMember;this.dueReturnDate=dueReturnDate;this.availability=availability;};Book.prototype={getTitle:function(){returnthis.title;},getAuthor:function(){returnthis.author;},getISBN:function(){returnthis.ISBN;},// For brevity, other getters are not shownupdateCheckoutStatus:function(bookID,newStatus,checkoutDate,checkoutMember,newReturnDate){this.id=bookID;this.availability=newStatus;this.checkoutDate=checkoutDate;this.checkoutMember=checkoutMember;this.dueReturnDate=newReturnDate;},extendCheckoutPeriod:function(bookID,newReturnDate){this.id=bookID;this.dueReturnDate=newReturnDate;},isPastDue:function(bookID){varcurrentDate=newDate();returncurrentDate.getTime()>Date.parse(this.dueReturnDate);}};

This probably works fine initially for small collections of books; however, as the library expands to include a larger inventory with multiple versions and copies of each book available, we may find the management system running slower and slower over time. Using thousands of book objects may overwhelm the available memory, but we can optimize our system using the Flyweight pattern to improve this.

We can now separate our data into intrinsic and extrinsic states

as follows: data relevant to the book object (title, author, etc.) is intrinsic, while the checkout

data (checkoutMember, dueReturnDate, etc.) is considered extrinsic.

Effectively, this means that only one Book object is

required for each combination of book properties. Itâs still a

considerable quantity of objects, but significantly fewer than we had

previously.

The following single instance of our book metadata combinations will be shared among all of the copies of a book with a particular title.

// Flyweight optimized versionvarBook=function(title,author,genre,pageCount,publisherID,ISBN){this.title=title;this.author=author;this.genre=genre;this.pageCount=pageCount;this.publisherID=publisherID;this.ISBN=ISBN;};

As we can see, the extrinsic states have been removed. Everything to do with library check-outs will be moved to a manager, and as the object data is now segmented, a factory can be used for instantiation.

Letâs now define a very basic factory. First, we must perform a check to see if a book with a particular title has been previously created inside the system. If it has, weâll return it; if not, a new book will be created and stored so that it can be accessed later. This makes sure that we only create a single copy of each unique intrinsic piece of data:

// Book Factory singletonvarBookFactory=(function(){varexistingBooks={},existingBook;return{createBook:function(title,author,genre,pageCount,publisherID,ISBN){// Find out if a particular book meta-data combination has been created before// !! or (bang bang) forces a boolean to be returnedexistingBook=existingBooks[ISBN];if(!!existingBook){returnexistingBook;}else{// if not, let's create a new instance of the book and store itvarbook=newBook(title,author,genre,pageCount,publisherID,ISBN);existingBooks[ISBN]=book;returnbook;}}};});

Next, we need to store the states that were removed from

the Book objects somewhere. Luckily, a manager (which

weâll be defining as a Singleton) can be used to encapsulate them.

Combinations of a Book object and the library member

thatâs checked it out will be called book records. Our

manager will be storing both and will also include checkout-related logic we stripped out

during our flyweight optimization of the Book

class.

// BookRecordManager singletonvarBookRecordManager=(function(){varbookRecordDatabase={};return{// add a new book into the library systemaddBookRecord:function(id,title,author,genre,pageCount,publisherID,ISBN,checkoutDate,checkoutMember,dueReturnDate,availability){varbook=bookFactory.createBook(title,author,genre,pageCount,publisherID,ISBN);bookRecordDatabase[id]={checkoutMember:checkoutMember,checkoutDate:checkoutDate,dueReturnDate:dueReturnDate,availability:availability,book:book};},updateCheckoutStatus:function(bookID,newStatus,checkoutDate,checkoutMember,newReturnDate){varrecord=bookRecordDatabase[bookID];record.availability=newStatus;record.checkoutDate=checkoutDate;record.checkoutMember=checkoutMember;record.dueReturnDate=newReturnDate;},extendCheckoutPeriod:function(bookID,newReturnDate){bookRecordDatabase[bookID].dueReturnDate=newReturnDate;},isPastDue:function(bookID){varcurrentDate=newDate();returncurrentDate.getTime()>Date.parse(bookRecordDatabase[bookID].dueReturnDate);}};});

The result of these changes is that all of the data thatâs been

extracted from the Book class is

now being stored in an attribute of the BookManager

singleton (BookDatabase)âsomething considerably more

efficient than the large number of objects we were previously using.

Methods related to book checkouts are also now based here, as they deal

with data thatâs extrinsic rather than intrinsic.

This process does add a little complexity to our final solution; however, itâs a small concern when compared to the performance issues that have been tackled. Data-wise, if we have 30 copies of the same book, we are now only storing it once. Also, every function takes up memory. With the Flyweight pattern, these functions exist in one place (on the manager) and not on every object, thus saving on memory use.

The Document Object Model (DOM) supports two approaches that allow objects to detect events: top down (event capture) and bottom up (event bubbling).

In event capture, the event is first captured by the outermost element and propagated to the innermost element. In event bubbling, the event is captured and given to the innermost element and then propagated to the outer elements.

One of the best metaphors for describing Flyweights in this context was written by Gary Chisholm and it goes a little like this:

Try to think of the flyweight in terms of a pond. A fish opens its mouth (the event), bubbles rise to the surface (the bubbling), a fly sitting on the top flies away when the bubble reaches the surface (the action). In this example we can easily transpose the fish opening its mouth to a button being clicked, the bubbles as the bubbling effect, and the fly flying away to some function being run.

Bubbling was introduced to handle situations in which a single event (e.g., a click) may be handled by multiple event handlers defined at different levels of the DOM hierarchy. Where this happens, event bubbling executes event handlers defined for specific elements at the lowest level possible. From there on, the event bubbles up to containing elements before going to those even higher up.

Flyweights can be used to tweak the event bubbling process further, as we will see shortly (Example 9-9).

For our first practical example, imagine we have a number of similar elements in a document with similar behavior executed when a user action (e.g., click, mouseover) is performed against them.

Normally what we do when constructing our own accordion component,

menu, or other list-based widget is bind a click event to each link

element in the parent container (e.g., $('ul li

a').on(..)). Instead of binding the click to multiple

elements, we can easily attach a Flyweight to the top of our container,

which can listen for events coming from below. These can then be handled

using logic that is as simple or complex as required.

As the types of components mentioned often have the same repeating markup for each section (e.g., each section of an accordion), thereâs a good chance the behavior of each element that may be clicked is going to be quite similar and relative to similar classes nearby. Weâll use this information to construct a very basic accordion using the Flyweight below.

A stateManager namespace is used here to

encapsulate our flyweight logic while jQuery is used to bind the initial

click to a container div. To ensure that no other

logic on the page is attaching similar handles to the container, an

unbind event is first applied.

Now to establish exactly what child element in the container is

clicked, we make use of a target

check, which provides a reference to the element that was clicked,

regardless of its parent. We then use this information to handle the

click event without actually needing to bind the event to specific

children when our page loads.

Example 9-9. Centralized event handling

Here is the HTML code:

<divid="container"><divclass="toggle"href="#">MoreInfo(Address)<spanclass="info">Thisismoreinformation</span></div><divclass="toggle"href="#">EvenMoreInfo(Map)<spanclass="info"><iframesrc="http://www.map-generator.net/extmap.php?name=London&address=london%2C%20england&width=500...gt;"</iframe></span></div></div>

Here is the JavaScript code:

varstateManager={fly:function(){varself=this;$("#container").unbind().on("click",function(e){vartarget=$(e.originalTarget||e.srcElement);if(target.is("div.toggle")){self.handleClick(target);}});},handleClick:function(elem){elem.find("span").toggle("slow");}};

The benefit here is that weâre converting many independent actions into a shared one (potentially saving on memory).

In our second example, weâll reference some further performance gains that can be achieved using Flyweights with jQuery.

James Padolsey previously wrote an article called 76

bytes for faster jQuery where he reminded us that each time

jQuery fires off a callback, regardless of type (filter, each, event

handler), weâre able to access the functionâs context (the DOM element

related to it) via the this

keyword.

Unfortunately, many of us have become used to the idea of wrapping

this in $() or jQuery(), which means that a new instance of

jQuery is unnecessarily constructed every time, rather than simply doing

this (Example 9-10):

Example 9-10. Using the Flyweight for performance optimization

$("div").on("click",function(){console.log("You clicked: "+$(this).attr("id"));});// we should avoid using the DOM element to create a// jQuery object (with the overhead that comes with it)// and just use the DOM element itself like this:$("div").on("click",function(){console.log("You clicked:"+this.id);});

James had wanted to use jQueryâs jQuery.text in the following context; however,

he disagreed with the notion that a new jQuery object had to be created

on each iteration:

$( "a" ).map( function () {

return $( this ).text();

});Now with respect to redundant wrapping, where possible with

jQueryâs utility methods, itâs better to use jQuery.methodName (e.g., jQuery.text) as opposed to jQuery.fn.methodName (e.g., jQuery.fn.text), where

methodName represents a utility such as each() or text. This avoids the need to call a further

level of abstraction or construct a new jQuery object each time our

function is called, as jQuery.methodName is what the library itself

uses at a lower-level to power jQuery.fn.methodName.

Because though not all of jQueryâs methods have corresponding

single-node functions, Padolsey devised the idea of a

jQuery.single utility.

The idea here is that a single jQuery object is created and used

for each call to jQuery.single (effectively meaning

only one jQuery object is ever created). The implementation for this can

be found below and, as weâre consolidating data for multiple possible

objects into a more central singular structure, it is technically also a

Flyweight.

jQuery.single=(function(o){varcollection=jQuery([1]);returnfunction(element){// Give collection the element:collection[0]=element;// Return the collection:returncollection;};});

An example of this in action with chaining is:

$("div").on("click",function(){varhtml=jQuery.single(this).next().html();console.log(html);});

Note

Although we may believe that simply caching our jQuery code

may offer equivalent performance gains, Padolsey claims that

$.single is still worth using and can perform

better. Thatâs not to say donât apply any caching at all, just be

mindful that this approach can assist. For further details about

$.single, I recommend reading Padolseyâs full

post.

Get Learning JavaScript Design Patterns now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.