Model View Presenter (MVP) is a derivative of the MVC design pattern that focuses on improving presentation logic. It originated at a company named Taligent in the early 1990s while they were working on a model for a C++ CommonPoint environment. While both MVC and MVP target the separation of concerns across multiple components, there are some fundamental differences between them.

For the purposes of this summary, we will focus on the version of MVP most suitable for web-based architectures.

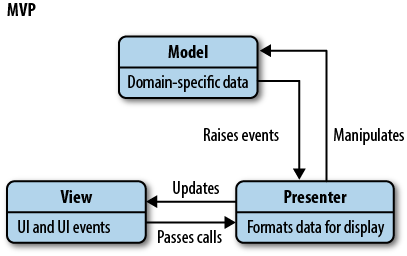

The P in MVP stands for presenter. Itâs a component that contains the user-interface business logic for the view. Unlike MVC, invocations from the view are delegated to the presenter, which are decoupled from the view and instead talk to it through an interface. This allows for all kinds of useful things, such as being able to mock views in unit tests (Figure 10-2).

The most common implementation of MVP is one that uses a Passive View (a view which is, for all intents and purposes, âdumbâ), containing little to no logic. If MVC and MVP are different, it is because the C and P do different things. In MVP, the P observes models and updates views when models change. The P effectively binds models to views, a responsibility that was previously held by controllers in MVC.

Solicited by a view, presenters perform any work to do with user requests and pass data back to them. In this respect, they retrieve data, manipulate it, and determine how the data should be displayed in the view. In some implementations, the presenter also interacts with a service layer to persist data (models). Models may trigger events, but itâs the presenters role to subscribe to them so that it can update the view. In this passive architecture, we have no concept of direct data binding. Views expose setters that presenters can use to set data.

The benefit of this change from MVC is that it increases the testability of our application and provides a more clean separation between the view and the model. This isnât however without its costs,as the lack of data binding support in the pattern can often mean having to take care of this task separately.

Although a common implementation of a Passive View is for the view to implement an interface, there are variations on it, including the use of events that can decouple the View from the Presenter a little more. As we donât have the interface construct in JavaScript, weâre using more a protocol than an explicit interface here. Itâs technically still an API, and itâs probably fair for us to refer to it as an interface from that perspective.

There is also a Supervising

Controller variation of MVP, which is closer to the MVC and

MVVM

patterns, as it provides data-binding from the Model directly from the

View. Key-value observing (KVO) plug-ins (such as Derick Baileyâs

Backbone.ModelBinding plug-in) tend to bring Backbone

out of the Passive View and more into the Supervising Controller or MVVM

variations.

MVP is generally used most often in enterprise-level applications where itâs necessary to reuse as much presentation logic as possible. Applications with very complex views and a great deal of user interaction may find that MVC doesnât quite fit the bill here as solving this problem may mean heavily relying on multiple controllers. In MVP, all of this complex logic can be encapsulated in a presenter, which can simplify maintenance greatly.

As MVP views are defined through an interface, and the interface is technically the only point of contact between the system and the view (other than a presenter), this pattern also allows developers to write presentation logic without needing to wait for designers to produce layouts and graphics for the application.

Depending on the implementation, MVP may be easier to automatically unit test than MVC. The reason often cited for this is that the presenter can be used as a complete mock of the user interface and so it can be unit tested independent of other components. In my experience this really depends on the languages in which we are implementing MVP (thereâs quite a difference between opting for MVP for a JavaScript project over one for, say, ASP.NET).

At the end of the day, the underlying concerns we may have with MVC will likely hold true for MVP, given that the differences between them are mainly semantic. As long as we are cleanly separating concerns into models, views, and controllers (or presenters), we should be achieving most of the same benefits regardless of the variation we opt for.

There are very few, if any architectural JavaScript frameworks that claim to implement the MVC or MVP patterns in their classical form, as many JavaScript developers donât view MVC and MVP as being mutually exclusive (we are actually more likely to see MVP strictly implemented when looking at web frameworks such as ASP.NET or GWT). This is because itâs possible to have additional presenter/view logic in our application and still consider it a flavor of MVC.

Backbone contributor of Boston-based Bocoup Irene Ros subscribes to this way of

thinking, as when she separates views out into their own distinct

components, she needs something to actually assemble them for her. This

could either be a controller route (such as a Backbone.Router, covered later in the book),

or a callback in response to data being fetched.

That said, some developers do feel that Backbone.js better fits the description of MVP than it does MVC. Their view is that:

The presenter in MVP better describes the

Backbone.View(the layer between View templates and the data bound to it) than a controller does.The model fits

Backbone.Model(it isnât greatly different to the models in MVC at all).The views best represent templates (e.g., Handlebars/Mustache markup templates).

A response to this could be that the view can also just be a View

(as per MVC), because Backbone is flexible enough to let it be used for

multiple purposes. The V in MVC and the P in MVP can both be

accomplished by Backbone.View because

theyâre able to achieve two purposes: both rendering atomic components

and assembling those components rendered by other views.

Weâve also seen that in Backbone the responsibility of a

controller is shared with both Backbone.View and

Backbone.Router and in the following example, we can

actually see that aspects of that are certainly true.

Our Backbone PhotoView uses the

Observer pattern to âsubscribeâ to changes to a Viewâs model in the line

this.model.bind("change",...). It

also handles templating in the render() method, but unlike some other

implementations, user interaction is also handled in the View (see

events).

varPhotoView=Backbone.View.extend({//... is a list tag.tagName:"li",// Pass the contents of the photo template through a templating// function, cache it for a single phototemplate:_.template($("#photo-template").html()),// The DOM events specific to an item.events:{"click img":"toggleViewed"},// The PhotoView listens for changes to// its model, re-rendering. Since tHere's// a one-to-one correspondence between a// **Photo** and a **PhotoView** in this// app, we set a direct reference on the model for convenience.initialize:function(){this.model.on("change",this.render,this);this.model.on("destroy",this.remove,this);},// Re-render the photo entryrender:function(){$(this.el).html(this.template(this.model.toJSON()));returnthis;},// Toggle the `"viewed"` state of the model.toggleViewed:function(){this.model.viewed();}});

Another (quite different) opinion is that Backbone more closely resembles Smalltalk-80 MVC, which we went through earlier.

As regular Backbone blogger Derick Bailey has previously put it, itâs ultimately best not to force Backbone to fit any specific design patterns. Design patterns should be considered flexible guides to how applications may be structured, and in this respect, Backbone fits neither MVC nor MVP. Instead, it borrows some of the best concepts from multiple architectural patterns and creates a flexible framework that just works well.

It is however worth understanding where and why these concepts originated, so I hope that my explanations of MVC and MVP have been of help. Call it the Backbone way, MV*, or whatever helps reference its flavor of application architecture. Most structural JavaScript frameworks will adopt their own take on classical patterns, either intentionally or by accident, but the important thing is that they help us develop applications that are organized, clean, and can be easily maintained.

Get Learning JavaScript Design Patterns now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.