Chapter 4. PHP Decision Making

In the last chapter, you started to get a feel for programming with PHP and some code basics. Now it’s time to expand your knowledge and ability with PHP. We’ll start with expressions and statements. Concepts from Chapter 3 and this chapter lay the foundations for adding your database, MySQL, which will be explored in Chapter 5.

Expressions

There are several building blocks of coding that you need to understand: statements, expressions, and operators. A statement is code that performs a task. Statements themselves are made up of expressions and operators. An expression is a piece of code that evaluates to a value. A value is a number, a string of text, or a Boolean.

Tip

A Boolean is an expression that results in a value of either TRUE or FALSE. For example, the expression 10 > 5 (10 is greater than 5) is a Boolean expression because the result is TRUE. All expressions that contain relational operators, such as the less-than sign (<), are Boolean. The Boolean operators are AND, OR, XOR, NOR, and NOT.

An operator is a code element that acts on an expression in some way. For instance, a minus sign can be used to tell the computer to decrement the value of the expression after it from the expression before it. The most important thing to understand about expressions is how to combine them into compound expressions and statements using operators. So we’re going to look at operators used to turn expressions into more complex expressions and statements.

The simplest form of expression is a literal or a variable. A literal evaluates to itself. Some examples of literals are numbers, strings, or constants. A variable evaluates to the value assigned to it. For instance, any of the expressions in Table 4-1 are valid.

|

Example |

Type |

|

1 |

A numeric value literal |

|

“Becker Furniture” |

A string literal |

|

TRUE |

A constant literal |

|

$user_name |

A variable with username as a string |

|

1+1 |

A numeric value expression that evaluates to a literal |

Although a literal or variable may be a valid expression, they aren’t expressions that do anything. You get expressions to do things such as math or assignment by linking them together with operators.

Tip

Assignment is a symbol that represents a specific action. For example, a plus sign (+) is an operator that represents addition.

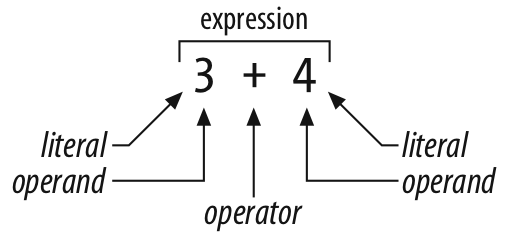

An operator combines simple expressions into more complex expressions by creating relationships between simple expressions that can be evaluated. For instance, if the relation you want to establish is the cumulative joining of two numeric values together, you could write “3 + 4”.

Figure 4-1 shows how the parts of an expression come together.

The numbers 3 and 4 are each valid expressions. The equation 3 + 4 is also a valid expression, whose value, in this case, happens to be 7. The plus sign (+) is an operator. The numbers to either side of it are its arguments,

or operands.

An argument or operand is something an operator takes action on; for example, an argument or operand could be a directive from your housemate to empty the dishwasher, and the operator empties the dishwasher. Different operators have different types and numbers of operands. Operators can also be overloaded, which means that they do different things in different contexts.

You’ve probably guessed from this information that two or more expressions connected by operators are called an expression. You’re right, as operators create complex expressions. The more subexpressions and operators, the longer and more complex the expression. But no matter what, as long as it equates to a value, it’s still an expression.

When expressions and operators are assembled to produce a piece of code that actually does something, you have a statement. We discussed statements in Chapter 3. They end in semicolons, which is the programming equivalent of a complete sentence.

For instance, $Margaritaville + $Sun_Tan_Application is an expression. It equates to something, which is the sum of the values of $Margaritaville + $Sun_Tan_Application, but it doesn’t do anything. While it’s an expression, the output doesn’t make any sense, but if you add the equals sign (=), $Fun_in_the_Sun = $Margaritaville + $Sun_Tan_Application;, you get a statement, because it does something. As Example 4-1 demonstrates, it assigns the sum of the values of $Margaritaville + $Sun_Tan_Application to $Fun_in_the_Sun.

<?php $Margaritaville = 3; // Three margaritas $Sun_Tan_Application = 2; // Two applications of sun tan $Fun_in_the_Sun = $Margaritaville + $Sun_Tan_Application; echo $Fun_in_the_Sun; ?>

Example 4-1 outputs:

5

There really isn’t much more to understand about expressions except for the assembly of them into compound expressions and statements using operators. Next, we’re going to discuss operators that are used to turn expressions into more complex expressions and statements.

Operator Concepts

PHP has many types of operators. The categories are:

Arithmetic operators

Array operators

Assignment operators

Bitwise operators

Comparison operators

Execution operators

Incrementing/decrementing operators

Logical operators

String operators

The operators are listed as found on http://www.zend.com/manual/language.operators.php. There are some operators we’re not going to discuss in order for you to get up and running with PHP as quickly as possible. These include some of the casting operators that we’ll just skim the surface of, for now. When working with operators, there are four aspects that are critical:

Number of operands

Type of operands

Order of precedence

Operator associativity

The easiest place to start is by talking about the operands.

Number of Operands

Depending on which operator you are using, it may take different numbers of operands. Many operators are used to combine two expressions into a more complex single expression; these are called binary operators. Binary operators include addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

Other operators take only one operand; these are called unary

operators. Think of the negation operator (-) that multiplies a numeric value by -1. The auto-increment and -decrement operators described in Chapter 3 are also unary operators.

A ternary

operator takes three operands. The shorthand for an if statement, which we’ll talk about later when discussing conditionals, takes three operands.

Types of Operands

You need to be mindful of the type of operand an operator is meant to work on, because certain operators expect their operands to be particular data types. PHP attempts to make your life as easy as possible by automatically converting operands to the data type that an operator is expecting. But there are times that an automatic conversion isn’t possible.

Mathematical operators are an example of where you need to be careful with your types. They take only numbers as operands. For example, when you try to multiply two strings, PHP can convert the strings to numbers. While "Becker" * "Furniture" is not a valid expression, it returns zero. Because the strings don’t contain simple numbers, an expression that is converted without an error is "70" * "80". This outputs to 5600. Although 70 and 80 are strings, PHP is able to convert them to the number type required by the mathematical operator.

There will be times when you want to explicitly set or convert a variable’s type. There are two ways to do this in PHP—first, by using settype to actually change the data type, or second, by casting, which temporarily converts the value. PHP uses casting to convert data types. When PHP does the casting for you automatically, it’s called implicit casting.

You can also specify data types explicitly, but it’s not something that you’ll likely need to do.

The cast types allowed are:

-

(int), (integer) Cast to integer

-

(bool), (boolean) Cast to Boolean

-

(float), (double), (real) Cast to float

-

(string) Cast to string

-

(array) Cast to array

-

(object) Cast to object

To use a cast, place it before the variable to cast, as in Example 4-2. The $test_string variable contains the string “1234”.

Keep in mind that it may not always be obvious what will happen when casting between certain types. You might run into problems if you don’t watch yourself when manipulating variable types.

Some binary operators such as the assignment operators have further restrictions on the lefthand operand. Because the assignment operator is assigning a value to the lefthand operator, it must be something that can take a value such as a variable. Example 4-3 demonstrates good and bad lefthand expressions.

3 = $locations; // bad - a value can not be assign to the literal 3 $a + $b = $c; //bad - the expression on the left isn't one variable $c = $a + $b; //OK $stores = "Becker"." "."Furniture"; // OK

Tip

There is a simpler way to remember this. The lefthand expression in assignment operations is known as an L-value. L-values in PHP are variables, elements of an array, and object properties. Don’t worry about object properties.

Order of precedence

The order of precedence of an operator determines which operator processes first in an expression. For instance, the multiplication and division process before addition and subtraction. You can see a simplified table at http://www.zend.com/manual/language.operators.php#language.operators.precedence.

If the operators have the same precedence, they are processed in the order they appear in the expression. For example, multiplication and division process in the order they appear in an expression, because they have the same precedence. Operators with the same precedence can occur in any order without affecting the result.

Most expressions do not have more than one operator of the same precedence level, or the order in which they process doesn’t change the result. As shown in Example 4-4, when adding and subtracting, it doesn’t matter whether you add or subtract first—the result is still 1.

2 + 4 − 5 == 1; 4 − 5 + 2 == 1; 4 * 5 / 2 == 10; 5 / 2 * 4 == 10; 2 + 4 − 5 == 1; 4 − 5 + 2 == 1; 4 * 5 / 2 == 10; 5 / 2 * 4 == 10;

When using expressions that contain operators of different precedence levels, the order can change the value of the expression. You can use parentheses, ( and ), to override the precedence levels or just to make the expression easier to read. Example 4-5 shows how to change the default precedence.

echo 2 * 3 + 4 + 1; 11 echo 2 * (3 + 4 + 1); 16

PHP has several levels of precedence, enough so that it’s difficult to keep track of them without checking a reference. Table 4-2 is a list of operators in PHP sorted by order of precedence from highest to lowest. Operators with the same level number are all of the same precedence.

Tip

The Association column lists operators that are right to left instead of left to right. We’ll discuss associativity next.

|

Operator |

Description |

Operands |

Association |

Level |

|

NEW |

Create new object |

Constructor call |

Right to left |

1 |

|

. |

Property access (dot notation) |

Objects |

2 | |

|

[ ] |

Array index |

Array, integer, or string |

2 | |

|

() |

Function call |

Function or argument |

2 | |

|

! |

Logical NOT |

Unary |

Right to left |

3 |

|

~ |

Bitwise NOT |

Unary |

Right to left |

3 |

|

|

Increment and decrement operators |

1value |

Right to left |

3 |

|

|

Unary plus, negation |

Number |

Right to left |

3 |

|

(int) |

Cast operators |

Unary |

Right to left |

3 |

|

(double) |

Cast operators |

Unary |

Right to left |

3 |

|

(string) |

Cast operators |

Unary |

Right to left |

3 |

|

(array) |

Cast operators |

Unary |

Right to left |

3 |

|

(object) |

Cast operators |

Unary |

Right to left |

3 |

|

@ |

Inhibit errors |

Unary |

Right to left |

3 |

|

|

Multiplication, division |

Numbers |

4 | |

|

|

Addition, subtraction |

Numbers |

5 | |

|

. |

Concatenation |

Strings |

5 | |

|

|

Bitwise shift left, bitwise shift right |

Binary |

6 | |

|

|

Comparison operators |

Numbers, strings |

7 | |

|

|

Equality, inequality |

Any |

8 | |

|

|

Identity, non-identity |

Any |

8 | |

|

& |

Bitwise AND |

Binary |

9 | |

|

^ |

Bitwise NOR |

Binary |

10 | |

|

| |

Bitwise OR |

Binary |

11 | |

|

&& |

Logical AND |

Boolean |

12 | |

|

|| |

Logical OR |

Boolean |

13 | |

|

? : |

Conditional |

Boolean |

Right to left |

14 |

|

= |

Assignment |

1value=any |

Right to left |

15 |

|

AND |

Logical AND |

Boolean |

16 | |

|

OR |

Logical OR |

Boolean |

17 | |

|

XOR |

Logical XOR |

Boolean |

18 |

Associativity

All operators process their operators in a certain direction. This direction is called associativity, and it depends on the type of operator. Most operators are processed from left to right, which is called left associativity. For example, in the expression 3 + 5 − 2, 3 and 5 are added together, and then 2 is subtracted from the addition, resulting in 8. Left associativity means that the expression is evaluated from left to right. Right associativity means the opposite.

Since it has right associativity, the assignment operator is one of the exceptions, since it has right associativity. The expression $a=$b=$c processes by $b being assigned the value of $c, and then $a being assigned the value of $b. This assigns the same value to all of the variables. If the assignment operator is right associative, the variables might not have the same value.

If you’re thinking that this is incredibly complicated, don’t worry. These rules are only enforced if you fail to be explicit about your instructions. Keep in mind that you should always use brackets in your expressions to make your actual meaning very clear. This helps both PHP and also other people who may need to read your code.

Relational Operators

In Chapter 3, we discussed assignment and math operators. Relational operators provide the ability to compare two operands and return either TRUE or FALSE regarding the comparison. An expression that returns only TRUE or FALSE is called a Boolean expression, which we discussed earlier in this chapter. These comparisons include tests for equality

and less than or greater than. These comparison operators allow you to tell PHP when to do something based on a comparison being true so decisions can be made in your code.

Equality

The equality operator,

a double equals sign (==), is used frequently. Using the single = in its place is a common logical error in programs, since it assigns values rather than tests equality.

If the two operands are equal, TRUE is returned; otherwise, FALSE is returned. If you’re echoing your results, TRUE is printed as 1 in your browser. FALSE is 0, which won’t display in your browser.

It’s a simple construct but it also allows you to test for conditions. If the operands are of different types, PHP attempts to convert them before comparing.

For example, '1' == 1 is true. Also, $a == 1 is true if the variable $a is assigned to 1.

If you don’t want the equals operator to automatically convert types, you can use the identity operator, a triple equals sign ===, which checks that the values and types are the same. For example, '1' === 1 is false because they’re different types, since a string doesn’t equal an integer.

Sometimes you might want to check to see whether two things are different. The inequality operator, an exclamation mark before the equals sign (!=), checks for the opposite of equality, which means not equal to.

'1' != 'A' // true '1' != '1' // false

Comparison operators

You may need to check for more than just equality. Comparison operators test the relationship between two values. You may be familiar with these from high school math. They include less than (<), less than or equal to (<=), greater than (>), and greater than or equal to (>=).

For example, 3<4 is TRUE, while 3<3 is FALSE but 3<=3 is TRUE.

Comparison operators are often used to check for something happening up until a set point. For example, a web store might offer free shipping if you purchase five or more items. So the code must compare the number of items to the number five before changing the shipping cost.

Logical operators

Logical operators work with the Boolean results of relational operators to build more complex logical expressions; there are four logical operators shown in Table 4-3.

|

Logical operator |

Meaning |

|

AND |

|

|

OR |

|

|

XOR |

|

|

NOT |

|

To test whether both operands are true, use the AND operator, also represented as double ampersands (&&). TRUE is returned only if both operands are TRUE; otherwise, FALSE is returned. See Table 4-3 for more information.

To test whether one operand is TRUE, use the OR operator, which is also represented as double vertical bars (||). TRUE is returned only if either or both operands are TRUE.

Tip

Using the OR operator can create tricky program logic problems. If PHP finds that the first operand is TRUE, it won’t evaluate the second operand. While this saves execution time, you need to be careful that the second operator doesn’t contain code that needs to be executed for your program to work properly.

To test whether either operand is TRUE

but not both, use XOR. XOR returns TRUE if one and only one operand is TRUE.

To negate a Boolean value, use the NOT operator represented as an exclamation point (!). It returns TRUE if the operand has a value of FALSE. It returns FALSE if the operand is TRUE.

Tip

If you accidentally use & instead of && or | instead of ||, you’ll end up getting the wrong operator. They compare binary data bit by bit. PHP converts your operands into binary data and applies the binary operators.

Because they have different precedence levels, AND and OR have two representations. Table 4-4 displays logical statements and their results.

Conditionals

Since we’ve been talking about variables, we should also mention conditionals, which, like variables, form a building block in our foundation of PHP development. They alter a script’s behavior according to the criteria set in the code. There are three primary elements of conditionals in PHP:

ifswitch? : :(shorthand for anifstatement)

PHP also supports a conditional called a switch statement. The switch statement is useful when you need to take different action based on the contents of a variable that may be set to one of a list of values.

The if Statement

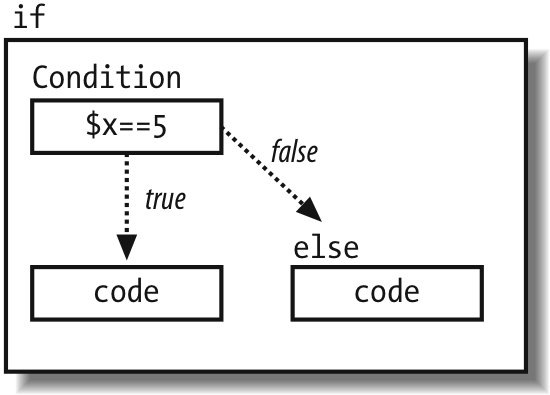

The if statement offers the ability to execute a block of code, if the supplied condition is TRUE; otherwise, the code block doesn’t execute. The type of condition can be any expression, including tests for nonzero, null, equality, variables, and returned values from functions.

No matter what, every single conditional you create includes a conditional clause. If a condition is true, the code block in curly brackets ({}) is executed. If not, PHP ignores it and moves to the second condition and continues through as many clauses as you write until PHP hits an else, then it automatically executes that block.

Figure 4-2 demonstrates how an if statement works. The else block always needs to come last and be treated as if it’s the default action. This is similar to the semicolon (;), which acts as the end of a sentence. Common true conditions are:

$var, if$varhas a value other than the empty set (0), an empty string, orNULLisset ($var), if$varhas any value other thanNULL, including the empty set or an empty stringTRUEor any variation thereof

We haven’t talked about the second bullet point, isset, yet. isset() is a function that checks whether a variable is set. A set variable is one that has a value other than NULL. Table 4-2 shows comparative and logical operators, which can be used in conjunction with parentheses, (), to create more complicated expressions.

The syntax for the if statement is:

if (conditional expression)

{

block of code;

}If the expression in the conditional block evaluates to TRUE, the block of code after it executes. In this example, if the variable $username is set to Admin, a welcome message is printed. Otherwise, nothing happens.

if ($username=="Admin") {

echo ('Welcome to the admin page.');

}The curly brackets aren’t needed if you want to execute only one statement, but it’s good practice to always use them, as it makes the code easier to read and more resilient to change.

The else statement

The else statement (see Example 4-6) provides for a default block of code that executes if the condition returned is FALSE. It must always be part of an if statement, as it doesn’t take a conditional itself.

if ($username == "Admin"){

echo ('Welcome to the admin page.');

}

else {

echo ('Welcome to the user page.');

}Remember to close out the code block from the if conditional if you used brackets to start the block of code. Similar to the if block, the else block should also use curly brackets to begin and end the code.

The elseif statement

All of this is great except for when you want to test for several conditions at a time. To do this, you can use the elseif statement. It allows for testing of additional conditions until one is found to be true or you hit the else block. Each elseif has its own code block that comes directly after the elseif condition. The elseif must come after the if statement and before an else statement if one exists.

The elseif structure is a little complicated, but Example 4-7 should help you understand it.

if ($username == "Admin"){

echo ('Welcome to the admin page.');

}

elseif ($username == "Guest"){

echo ('Please take a look around.');

}

else {

echo ("Welcome back, $username.");

}Here you can check for and take different action based on two values for $username. Then you also have the option to do something else if the $user_name isn’t one of the first two.

The next construct builds on the concepts of the if/else statement, but it allows you to efficiently check the results of an expression to many values without having a separate if/else for each value.

The ? Operator

The ? operator is a ternary operator, meaning it takes three operands. It works like an if statement but returns a value from one of the two expressions. The conditional expression determines the value of the expression. A colon (:) is used to separate the expressions:

{expression} ? return_when_expression_true : return_when_expression_false;

Example 4-8 tests a value and returns a different string based on it being TRUE or FALSE.

<?php

$logged_in = TRUE;

$user = "Admin";

$banner = ($logged_in==TRUE)?"Welcome back $user!":"Please login.";

echo "$banner";

?>Example 4-8 produces:

Welcome back Admin!

This can be pretty useful for checking errors. Now, let’s look at a statement that lets you check an expression against a list of possible values to pick the executable code.

The switch Statement

The switch statement compares an expression to numerous values. It’s very common to have an expression, such as a variable, for which you’ll want to execute different code for each value stored in the variable. For example, you might have a variable called $action, which may have the values add, modify, and delete. The switch statement makes it easy to define a block of code to execute for each of those values.

To illustrate the difference between using the if statement and switch to test a variable for several values, we’ll show you the code for the if statement (in Example 4-9), and then for the switch statement (in Example 4-10).

if ($action == "ADD") {

echo "Perform actions for adding.";

echo "As many statements as you like can be in each block.";

}

elseif ($action == "MODIFY") {

echo "Perform actions for modifying.";

}

elseif ($action == "DELETE") {

echo "Perform actions for deleting.";

}switch ($action) {

case "ADD":

echo "Perform actions for adding.";

echo "As many statements as you like can be in each block.";

break;

case "MODIFY":

echo "Perform actions for modifying.";

break;

case "DELETE":

echo "Perform actions for deleting.";

break;

}The switch statement works by taking the value after the switch keyword and comparing it to the cases in the order they appear. If no case matches, no code is executed. Once a case matches, the code is executed. The code in subsequent cases also executes until the end of the switch statement or until a break keyword. This is useful for processes that have several sequential steps. If the user has already done some of the steps, he can jump into the process where he left off.

Tip

The expression after the switch statement must evaluate to a simple type like a number, integer, or string. An array can be used only if a specific member of the array is referenced as a simple type.

There are numerous ways to tell PHP to not execute cases besides the matching case.

Breaking out

If you want only the code in the matching block to execute, you can place a break keyword at the end of that block. When PHP comes across the break keyword,

processing jumps to the next line after the entire switch statement. Example 4-11 illustrates how processing works with no break statements.

$action="ASSEMBLE ORDER";

switch ($action) {

case "ASSEMBLE ORDER":

echo "Perform actions for order assembly.<br>";

case "PACKAGE":

echo "Perform actions for packing.<br>";

case "SHIP":

echo "Perform actions for shipping.<br>";

}

echo "Perform actions for shipping.<br>";

}

?>If the value of $action is "ASSEMBLE ORDER", the result is:

Perform actions for order assembly. Perform actions for packing. Perform actions for shipping.

However, if a user had already assembled an order, a value of "PACKAGE" produces the following:

Perform actions for packing. Perform actions for shipping.

Defaulting

The case statement also provides a way to do something if none of the other cases match, which is similar to the else statement in an if, elseif, else block.

Use DEFAULT: for the switches last case statement, as shown in Example 4-12.

switch ($action) {

case "ADD":

echo "Perform actions for adding.";

break;

case "MODIFY":

echo "Perform actions for modifying.";

break;

case "DELETE":

echo "Perform actions for deleting.";

break;

default:

echo "Error: Action must be either ADD, MODIFY, or DELETE.";

}The switch statement also supports the alternate syntax in which the switch and endswitch keywords define the start and end of the switch instead of the curly braces {}, as shown in Example 4-13.

switch ($action):

case "ADD":

echo "Perform actions for adding.";

break;

case "MODIFY":

echo "Perform actions for modifying.";

break;

case "DELETE":

echo "Perform actions for deleting.";

break;

default:

echo "Error: Action must be either ADD, MODIFY, or DELETE.";

endswitch;You’ve learned that you can have your programs execute different code based on conditions called expressions. The switch statement provides a convenient format for checking the value of an expression against many possible values.

Looping

Now change the flow of your PHP program based on comparisons, but if you want to repeat a task until a comparison is FALSE, you will need to use looping. Each time the code in the loop executes, it is called an iteration. It’s useful for many common tasks such as displaying the results of a query by looping through the returned rows. PHP provides the while,

for, and while . . . do constructs to perform loops.

Each of the loop constructs requires two basic pieces of information. First, when to stop looping is defined just like the comparison in an if statement. Second, the code to perform is also required and specified either on a single line or within curly braces. A logical error would be to omit the code in the loop, causing an infinite

loop.

The code is executed as long as the expression evaluates to TRUE. To avoid an infinite loop, which would loop forever, your code should affect the expressions so that it becomes FALSE. When this happens, the loop stops, and execution continues with the next line of code, following the logical loop.

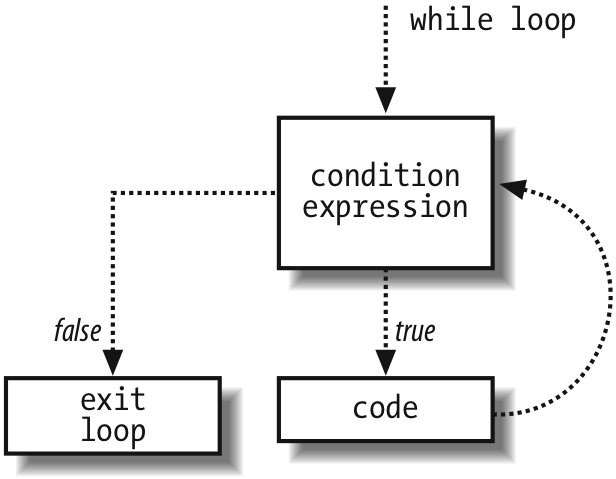

while Loops

The while loop takes the expression followed by the code to execute. Figure 4-3 illustrates how a while loop processes.

The syntax is for a while loop is:

while (expression) {code to execute; }

An example is shown in Example 4-14.

<?php

$num = 1;

while ($num <= 10){

print "Number is $num<br />\n";

$num++;

}

print 'Done.';

?>Example 4-14 produces:

Number is 1 Number is 2 Number is 3 Number is 4 Number is 5 Number is 6 Number is 7 Number is 8 Number is 9 Number is 10 Done.

Before the loop begins, the variable $num is set to 1. This is called initializing a counter variable. Each time the code block executes, it increases the value in $num by 1 with the statement $num++;. After 10 iterations, the evaluation $num <= 10 becomes FALSE and the loop stops, which then prints Done..

do . . . while Loops

The do . . . while loop takes an expression such as a while statement but places it at the end. The syntax is:

do {

code to execute;

} (expression);This loop is useful when you want to execute the block of code once regardless of the value in the expression. For example, let’s count to 10 with this loop, as in Example 4-15.

Example 4-15 produces the same results as Example 4-14; if you change the value of $num to 11, the loop processes differently.

<?php

$num = 11;

do {

echo $num;

$num++;

} while ($num <= 10);

?>This produces:

11

The code in the loop displays 11 because the loop always executes at least once. Following the pass, while evaluates to FALSE, causing execution to drop out of the do . . . while loop.

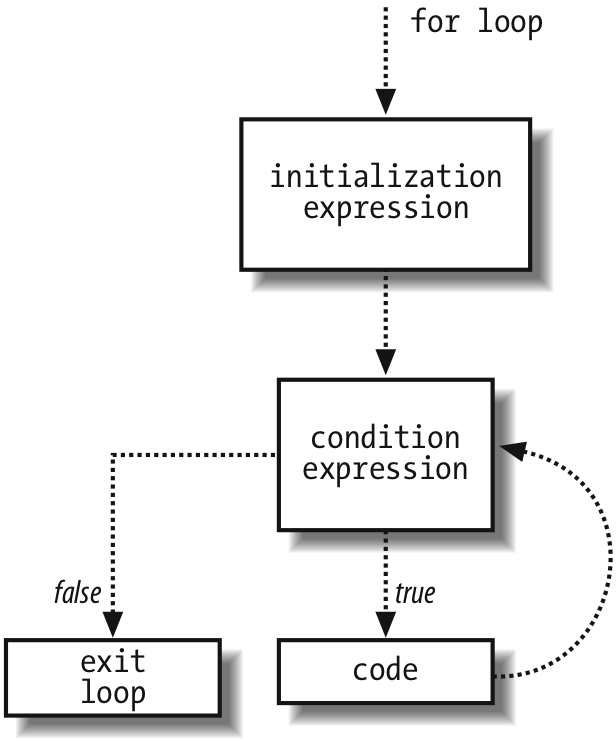

for Loops

for loops provide the same general functionality as while loops, but also provide for a predefined location for initializing and changing a counter value. Their syntax is:

for (initialization expression;test expression;modification expression){code that is executed; }

Figure 4-4 shows a flowchart for a for loop.

An example for loop is:

<?php

for ($num = 1; $num <= 10; $num++) {

print "Number is $num<br />\n";

}

?>This produces:

Number is 1 Number is 2 Number is 3 Number is 4 Number is 5 Number is 6 Number is 7 Number is 8 Number is 9 Number is 10

When your PHP program process the for loop, the initialization portion is evaluated. For each iteration of the portion that increments, the counter executes, followed by a check to see whether you’re done. The result is a much more compact and easy-to-read statement.

Tip

When specifying your for loop, if you don’t want to include one of the expressions, such as the initialization expression, you may omit it, but you must still include the separating semicolons (;). Example 4-16 shows the usage of a for loop without the initialization expression.

Breaking Out of a Loop

PHP provides the equivalent of an emergency stop button for a loop: the break statement. Normally, the only way out of a loop is to satisfy the expression that determines when to stop the loop. If the code in the loop finds an error that makes continuing the loop pointless or impossible, you can break out of the loop by using the break statement. It’s like getting your shoelace stuck in an escalator. It really doesn’t make any sense for the escalator to keep going!

Possible problems you might encounter in a loop include running out of space when writing to a file or attempting to divide by zero. In Example 4-16, we simulate what can happen if you divide based on an unknown entry initialized from a form submission (that could be a user-supplied value). If your user is malicious or just plain careless, she might enter a negative value where you are expecting a positive value (although this should be caught in your form validation process). In the code that is executed as part of the loop, the code checks to make sure $counter is not equal to zero. If it is, the code calls break.

<?php

$counter = -3;

for (; $counter < 10; $counter++){

// Check for division by zero

if ($counter == 0){

echo "Stopping to avoid division by zero.";

break;

}

echo "100/$counter<br />";

}

?>This displays:

100/−3 100/−2 100/−1 Stopping to avoid division by zero.

Of course, there may be times when you don’t want to just skip one execution of the loop code. The continue

statement performs this for you.

continue Statements

You can use the continue statement to stop processing the current block of code in a loop and jump to the next iteration of the loop. It’s different from break; in that it doesn’t stop processing the loop entirely. You’re basically skipping ahead to the next iteration. Make sure you are modifying your test variable before the continue statement, or an infinite loop is possible.

Example 4-17 shows the preceding example using continue instead of break.

<?php

$counter =− 3;

for (; $counter < 10; $counter++){

// Check for division by zero

if ($counter == 0){

echo "Skipping to avoid division by zero.<br />";

continue;

}

echo "100/$counter<br />";

}

?>Example 4-17 displays:

100/−3 100/−2 100/−1 Skipping to avoid division by zero. 100/1 100/2 100/3 100/4 100/5 100/6 100/7 100/8 100/9

Notice that the loop skipped over the $counter value of zero but continued with the next value.

We’ve now covered all of the major program flow language constructs. We’ve discussed the building blocks for controlling program flow in your programs. Expressions can be as simple as TRUE or FALSE and as complex as relational comparison with logical operators. The expressions combined with program flow control constructs like the if statement and switch make decision making easy.

We also discussed while, while . . . do, and for loops. Loops are very useful for common dynamic web page tasks such as displaying the results from a query in an HTML table.

Chapter 4 Questions

- Question 4-1.

What is a statement?

- Question 4-2.

What is a code element that acts on an expression?

- Question 4-3.

What does an operator combine?

- Question 4-4.

What is the plus (

+) sign?- Question 4-5.

What is a binary operator?

- Question 4-6.

What is a ternary operator?

- Question 4-7.

Do mathematical operators take letters as operands?

- Question 4-8.

What type of operand is an Array Index?

- Question 4-9.

If you use two ampersands (

&&) instead of one (&), will you get an error?- Question 4-10.

What does

isset()do?- Question 4-11.

Write a

switchstatement that adds, subtracts, multiplies, or divides x using the action variable.- Question 4-12.

What does the

breakkeyword do?- Question 4-13.

Write a

forloop to count from 10 to 1.

See the Appendix for the answers to these questions.

Get Learning PHP and MySQL now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.