Chapter 4. Managing Data Flow: Controllers and Models

Remove all the traffic lights, yellow lines, one-way systems, and road markings, and let blissful anarchy prevail. I imagine it would produce a kind of harmony.

Sadie Jones

Sadie Jones’s advice notwithstanding, Rails does not share her affection for blissful anarchy. It’s time to meet the key player in Rails applications. Controllers are the components that determine how to respond to user requests and coordinate responses. They’re at the heart of what many people think of as “the program” in your Rails applications, though in many ways they’re more of a switchboard. They connect the different pieces that do the heavy lifting, providing a focal point for application development. The model is the foundation of your application’s data structures, which will let you get information into and out of your databases.

Warning

Controllers are important, certainly a “key player,” but don’t get too caught up in them. When you’re coming from other development environments, it’s easy to think that controllers are the main place you should put application logic. As you get deeper into Rails, you’ll likely learn the hard way that a lot of code you thought belonged in the controller really belonged in the model, or sometimes in the view.

Getting Started, Greeting Guests

Controllers are Ruby objects. They’re stored in the app/controllers directory of your application. Each controller has a name, and the object inside of the controller file is called nameController.

Demonstrating controllers without getting tangled in all of the other Rails components is difficult, so for an initial tour, the application will be incredibly simple. (You can see the first version of it in ch04/guestbook01.) Guestbooks were a common (if kind of annoying) feature on early websites, letting visitors “post messages” so that the site’s owner could tell who’d been there. (The idea has since evolved into more sophisticated messaging, like Facebook’s Timeline.)

Note

If you’ve left any Rails applications from earlier chapters running under rails server, it would be wise to turn them off before starting a new application. Remember, you can stop the server using Ctrl-C.

To get started, create a new Rails application, as we did in Chapter 1. If you’re working from the command line, type:

rails new guestbook

Rails will create the usual pile of files and folders. Next, you’ll want to change to the guestbook directory and create a controller:

cd guestbook rails generate controller entries create app/controllers/entries_controller.rb invoke erb create app/views/entries invoke test_unit create test/controllers/entries_controller_test.rb invoke helper create app/helpers/entries_helper.rb invoke test_unit invoke assets invoke coffee create app/assets/javascripts/entries.coffee invoke scss create app/assets/stylesheets/entries.scss

If you then look at app/controllers/entries_controller.rb, which is the main file we’ll work with here, you’ll find:

class EntriesController < ApplicationController end

This doesn’t do very much. However, there’s an important relationship in that first line. Your EntriesController inherits from ApplicationController. The ApplicationController object lives in app/controllers/application_controller.rb, and it also doesn’t do very much initially, but if you ever need to add functionality that is shared by all of the controllers in your application, you can put it into the ApplicationController object.

To make this controller actually do something, we’ll add a method. For right now, we’ll call it sign_in, creating the very simple object in Example 4-1.

Example 4-1. Adding an initial method to an empty controller

class EntriesController < ApplicationController def sign_in end end

We’ll also need a view, so that Rails has something it can present to visitors. You can create a sign_in.html.erb file in the app/views/entries/ directory, and then edit it, as shown in Example 4-2.

Note

You can also have Rails create a method in the controller, as well as a basic view at the same time that it created the controller, by typing:

rails generate controller entries sign_in

You can work either way, letting Rails generate as much (or as little) code as you like.

Example 4-2. A view that lets users see a message and enter their name

<h1>Hello <%= @name %></h1> <%= form_tag action: 'sign_in' do %> <p>Enter your name: <%= text_field_tag 'visitor_name', @name %></p> <%= submit_tag 'Sign in' %> <% end %>

Example 4-2 has a lot of new pieces to it because it’s using helper methods to create a basic form. Helper methods take arguments and return text, which in this case is HTML that helps build your form. The following particular helpers are built into Rails, but you can also create your own:

-

The

form_tagmethod takes the name of our controller method,sign_in, as its:actionparameter. -

The

text_field_tagmethod takes two parameters and uses them to create a form field on the page. The first,visitor_name, is the identifier that the form will use to describe the field data it sends back to the controller, while the second is default text that the field will contain. If the user has filled out this form previously, and our controller populates the@namevariable, it will list the user’s name. Otherwise, it will be blank. -

The last helper method,

submit_tag, provides the button that will send the data from the form back to the controller when the user clicks it.

Once again, you’ll need to enable routing for your controller. You’ll need to edit the config/routes.rb file. Add the following lines at the top of the file inside the do block:

get 'entries/sign_in' => 'entries#sign_in' post 'entries/sign_in' => 'entries#sign_in'

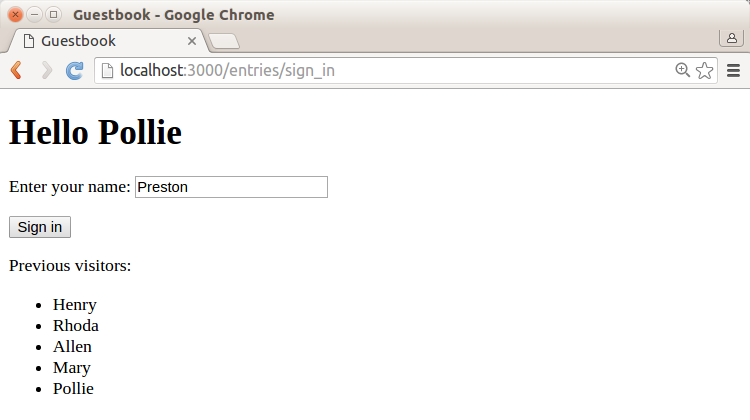

If you start up the server and visit http://localhost:3000/entries/sign_in, you’ll see a simple form like Figure 4-1.

Figure 4-1. A simple form generated by a Rails view

Now that we have a way to send data to our controller, it’s time to update the controller so that it does something with that information. In this very simple case, it just means adding a line, as shown in Example 4-3.

Example 4-3. Making the sign_in method do something

class EntriesController < ApplicationController

def sign_in

@name = params[:visitor_name]

end

endThe extra line gets the visitor_name parameter from the request header sent back by the client and puts it into @name. (If there wasn’t a visitor_name parameter, as would be normal the first time this page is loaded, @name will just be blank.)

If you enter a name into the form, you’ll now get a pretty basic hello message in return, as shown in Figure 4-2. The name will also be sitting in the form field for another round of greetings.

Figure 4-2. A greeting that includes the name that was entered

Warning

If, instead of Figure 4-2, you get a strange error message about “wrong number of arguments (1 for 0),” check your code carefully. You’ve probably added a space between params and [, which produces a syntax error whose description isn’t exactly clear.

The controller is now receiving information from the user and passing it to a view, which can then pass more information.

There is one other minor point worth examining before we move on, though: how did Rails convert the http://localhost:3000/entries/sign_in URL into a call to the sign_in method of the entries controller? If you look in the config directory of your application, you’ll find the routes.rb file, which contains the rules we enabled for choosing what gets called when a request comes in:

get 'entries/sign_in' => 'entries#sign_in' post 'entries/sign_in' => 'entries#sign_in'

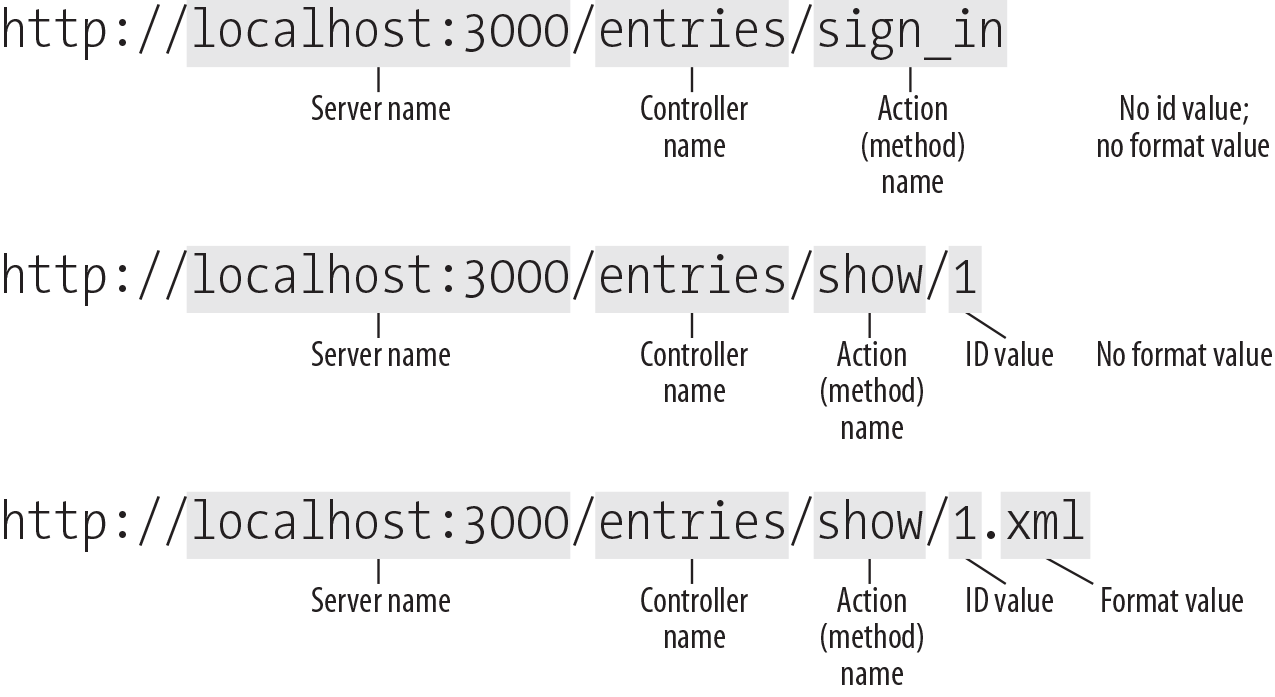

In this case, the URL entries/sign_in maps the controller to an action separated by a #; in this example entries is the controller and sign_in is the action (see Figure 4-3). Also, notice we have two separate entries, one for get and another for post. We will talk more about these in Chapter 5, but our get route allows us to make a request for data, and our post route allows us to send data to that same route.

Figure 4-3. How the default Rails routing rules break a URL down into component parts to decide which method to run

Application Flow

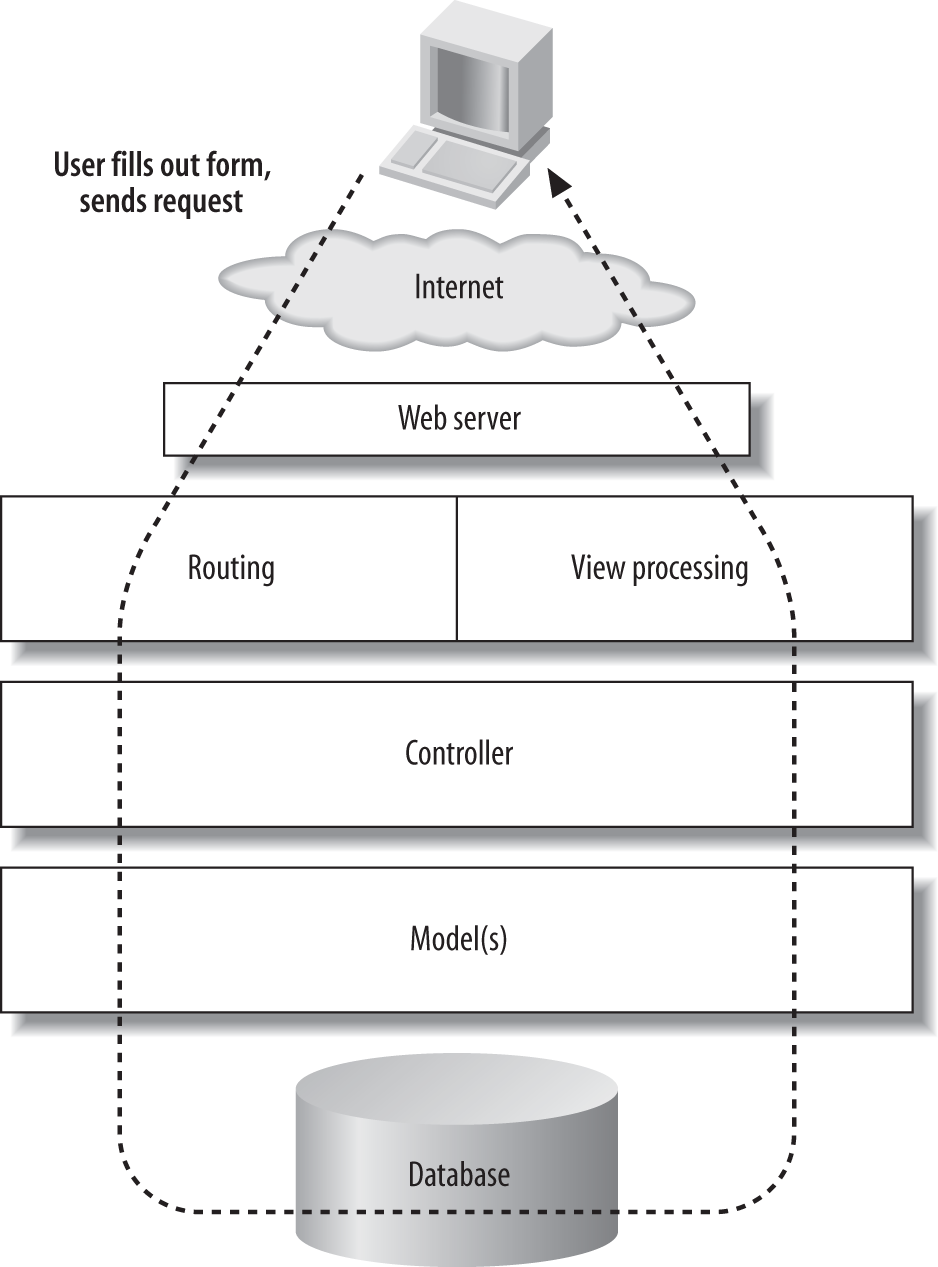

The Rails approach to handling requests, shown in Figure 4-4, has a lot of moving parts between users and data.

Rails handles URL processing instead of letting the web server pick which file to execute in response to the request. This allows Rails to use its own conventions, called routing, for deciding how a request gets handled, and it allows developers to create their own routing conventions to meet their applications’ needs.

The router sends the request information to a controller. The controller, centralizing the logic for responding to different kinds of requests, decides how to handle the request. The controller may interact with a data model (or several), and those models will interact with the database if necessary. The person writing the controller never has to touch SQL, though, and even the person writing the model should be able to stay away from it.

Once the controller has gathered and processed the information it needs, it sends that data to a view for rendering. The controller can pick and choose among different views if it needs to, making it easy to throw an XML rendering on a controller that was originally expecting to be part of an HTML-generating process. You could offer several different kinds of HTML—basic, Ajax, or meant for mobile—from your applications if necessary. Rails can even, at the developer’s discretion, generate basic views automatically, a feature called scaffolding. Scaffolding makes it extremely easy to get started on the data management side of an application without getting too hung up on its presentation.

Figure 4-4. How Rails breaks down web applications

The final result comes from the view, and Rails sends it along to the user. The user, of course, doesn’t need to know how all of this came to pass—she just gets the final view of the information, which hopefully is what she wanted.

Now that you’ve seen how this works in the big picture, it’s time to return to the details of making it happen.

Keeping Track: A Simple Guestbook

Most applications will need to do more with data—typically, at least, they’ll store the data and present it back as appropriate. It’s time to extend this simple application so that it keeps track of users who have stopped by, as well as greeting them. This requires using models. (The complete application is available in ch04/guestbook02.)

Warning

As Chapter 5 will make clear, in most application development, you will likely want to create your models by letting Rails create a scaffold, since Rails won’t let you create a scaffold after a model with the same name already exists. Nonetheless, understanding the more manual approach will make it much easier to work on your applications in the long run.

Connecting to a Database Through a Model

Keeping track of visitors will mean setting up and using a database. This should be easy when you’re in development mode, as Rails now defaults to SQLite, which doesn’t require explicit configuration. (When you deploy, you’ll still want to set up a database, typically MySQL or Postgres, as discussed in Chapter 20.) To test whether SQLite is installed on your system, try issuing the command sqlite3 -help from the command line. If it’s there, you’ll get a help message. If not, you’ll get an error, and you’ll need to install SQLite.

Once the database engine is functioning, it’s time to create a model. Once again, it’s easiest to use generate to lay a foundation, and then add details to that foundation. This time, we’ll create a simple model instead of a controller and call the model entry:

$rails generate model entry invoke active_record create db/migrate/20110221152951_create_entries.rb create app/models/entry.rb invoke test_unit create test/models/entry_test.rb create test/fixtures/entries.yml

For our immediate purposes, two of these files are critical. The first is app/models/entry.rb, which is where all of the Ruby logic for handling a person will go. The second, which defines the database structures and thus needs to be modified first, is in the db/migrate/ directory. It will have a name like [timestamp]_create_entries.rb, where [timestamp] is the date and time when it was created. It initially contains what’s shown in Example 4-4.

Example 4-4. The default migration for the entry model

1 class CreateEntries < ActiveRecord::Migration 2 def change 3 create_table :entries do |t| 4 5 t.timestamps 6 end 7 end 8 end

There’s a lot to examine here before we start making changes. First, note on line 1 that the class is called CreateEntries. The model may be for an entry, but the migration will create a table for more than one entry. Rails names tables (and migrations) using the plural form can handle most common English irregular pluralizations. (In cases where the singular and plural would be the same, you end up with an s added for the plural, so deer become deers and sheep become sheeps.) Many people find this natural, but other people hate it. For now, just go with it—fighting Rails won’t make life any easier.

Also on line 1, you can see that this class inherits most of its functionality from the Migration class of ActiveRecord. ActiveRecord is the Rails library that handles all the database interactions. (You can even use it separately from Rails, if you want to.)

The action begins on line 2 with the change method. Rails used to have separate self.up and self.down methods, one to build tables and one to take them down, but Rails 3.1 got smarter. It’s smart enough to understand how to run change backward to roll back the migration—effectively it provides you with “undo” functionality automatically.

Note

This example takes the slow route through creating a model so you can see what happens. In the future, if you’d prefer to move more quickly, you can also add the names and types of data on the command line, as you will do when generating scaffolding in Chapter 5.

The change method operated on a table called entries. Note that the migration is not concerned with what kind of database it works on. That’s all handled by the configuration information. You’ll also see that migrations, despite working pretty close to the database, don’t need to use SQL—though if you really want to use SQL, it’s available.

Storing the names people enter into this very simple application requires adding a single column:

create_table :entries do |t| t.string :name t.timestamps end

The new line refers to the table (t) and creates a column of type string, which will be accessible as :name.

Note

In older versions of Rails, that new line would have been written:

t.column :name, string

The old version still works, and you’ll definitely see migrations written this way in older applications and documents. The new form is a lot easier to read at a glance, though.

The t.timestamps line is there for housekeeping, tracking “created at” and “updated at” information. Rails also will automatically create a primary key, :id, for the table. Once you’ve entered the new line (at line 4 of Example 4-4), you can run the migration with:

$ rails db:migrate (in /Users/simonstl/rails/guestbook) //you will have a different path here == CreateEntries: migrating ================================================== -- create_table(:entries) -> 0.0021s == CreateEntries: migrated (0.0022s) =========================================

Note

Previous to Rails 5, commands like db:migrate were Rake tasks, so you would run rake db:migrate to migrate the database. When to use rails and when to use rake was a source of confusion for many Rails newcomers, so now all commands can be run with the rails command.

In this case, the db:migrate task runs all of the previously unapplied change (or self.up) migrations in your application’s db/migrate/ folder. db:rollback gives you an undo option for the previous command by running the change methods backward (or the self.down methods if present).

Now that the application has a table with a column for holding names, it’s time to turn to the app/models/entry.rb file. Its initial contents are very simple:

class Entry < ApplicationRecord end

The Entry class inherits from ApplicationRecord, which in turn inherits from the ActiveRecord library’s Base class, but has no functionality of its own. Previous to Rails 5 all models inherited directly from ActiveRecord, but now models inherit from ApplicationRecord, which is located in app/models/application_record.rb.

class ApplicationRecord < ActiveRecord::Base self.abstract_class = true end

You can see this class simply inherits from ActiveRecord::Base, and also is set as an abstact class, which, if you are familiar with object-oriented programming, means the class can only be inherited from and not instantiated. This allows for a single point of entry for your models.

Warning

Remember that the names in your models also need to stay away from the list of reserved words presented at Ruby Magic or Reserved Words in Ruby on Rails. Don’t worry, Rails won’t let you shoot yourself in the foot. If you attempt to name a model using a reserved word, Rails will give you a friendly warning.

Connecting the Controller to the Model

As you may have guessed, the controller is going to be the key component transferring data that comes in from the form to the model, and then it will be the key component transferring that data back out to the view for presentation to the user.

Storing data using the model

To get started, the controller will just blindly save new names to the model, using the code highlighted in Example 4-5.

Example 4-5. Using ActiveRecord to save a name

class EntriesController < ApplicationController

def sign_in

@name = params[:visitor_name]

@entry = Entry.create({:name => @name})

end

endThe preceding highlighted line combines three separate operations into a single line of code, which might look like:

@entry = Entry.new @entry.name = @name @entry.save

The first step creates a new variable, @entry, and declares it to be a new Entry object. The next line sets the name property of @entry—effectively setting the future value of the column named “name” in the entries table—to the @name value that came in through the form. The third line saves the @entry object to the table. There is nothing special about the @entry variable name. There is no special connection to that variable and Entry.create. We could have said @foo = Entry.create, and as long as we were consistant with our variable name, it would be OK.

Warning

In web development, saving values directly to the database like this is not considered a security risk or a poor practice. Chapter 5 will cover strong parameters and whitelisting of database values. Production applications should use the practices set forth in Chapter 5, but for the purposes of seeing how models and controllers interact, what we are doing here will suffice.

The Entry.create approach assumes you’re making a new object, takes the values to be stored as named parameters, and then saves the object to the database.

Note

Both the create and the save methods return a boolean value indicating whether or not saving the value to the database was successful. For most applications, you’ll want to test this and return an error if there was a failure.

These are the basic methods you’ll need to put information into your databases with ActiveRecord. (There are many shortcuts and more elegant syntax, as Chapter 5 will demonstrate.) This approach is also a bit too simple. If you visit http://localhost:3000/entries/sign_in/, you’ll see the same empty form that was shown in Figure 4-1. However, because @entry.create was called, an empty name will have been written to the table. The log data that appears in the server’s terminal window shows:

(0.1ms) begin transaction

SQL (87.3ms) INSERT INTO "entries" ("created_at", "name", "updated_at")

VALUES (?, ?, ?) [["created_at", Mon, 20 Feb 2012 16:18:14 UTC +00:00],

["name", nil],["updated_at", Mon, 20 Feb 2012 16:18:14 UTC +00:00]]

The nil is the problem here because it really doesn’t make sense to add a blank name every time someone loads the form without sending a value. On the bright side, we have evidence that Rails is putting information into the entries table, and if we enter a name, say “Preston,” we can see the name being entered into the table:

(0.1ms) begin transaction

SQL (0.6ms) INSERT INTO "entries" ("created_at", "name", "updated_at")

VALUES (?, ?, ?) [["created_at", Mon, 20 Feb 2012 16:18:48 UTC +00:00],

["name", "Preston"], ["updated_at", Mon, 20 Feb 2012 16:18:48 UTC +00:00]]

It’s easy to fix the controller so that NULLs aren’t stored—though as we’ll see in Chapter 7, this kind of validation code really belongs in the model. Two lines, highlighted in Example 4-6, will keep Rails from entering a lot of blank names.

Example 4-6. Keeping blanks from turning into permanent objects

class EntriesController < ApplicationController

def sign_in

@name = params[:visitor_name]

unless @name.blank?

@entry = Entry.create({:name => @name})

end

end

endNow Rails will check the @name variable to make sure that it has a value before putting it into the database. unless @name.blank? will test for both nil values and blank entries. (blank? is a Rails method extending Ruby’s String objects.)

If you want to get rid of the NULLs you put into the database, you can run rails db:rollback and rails db:migrate (or rails db:migrate:redo to combine them) to drop and rebuild the table with a clean copy. In this case, you should stop the server before running rails and restart it when you’re done.

== CreateEntries: reverting ==================================================

-- drop_table(:entries)

-> 0.0012s

== CreateEntries: reverted (0.0013s) =========================================

== CreateEntries: migrating ==================================================

-- create_table(:entries)

-> 0.0015s

== CreateEntries: migrated (0.0016s) =========================================

If you want to enter a few names to put some data into the new table, go ahead. The next example will show how to get them out.

Retrieving data from the model and showing it

Storing data is a good thing, but only if you can get it out again. Fortunately, it’s not difficult for the controller to tell the model that it wants all the data or for the view to render it. For a guestbook, it’s especially simple, as we just want all of the data every time.

Getting the data out of the model requires one line of additional code in the controller, highlighted in Example 4-7.

Example 4-7. A controller that also retrieves data from a model

class EntriesController < ApplicationController

def sign_in

@name = params[:visitor_name]

if !@name.blank? then

@entry = Entry.create({:name => @name})

end

@entries = Entry.all

end

endThe Entry object includes a find method (Entry.all); like new and save, it is inherited from its parent ActiveRecord::Base class without any additional programming.

Next, the view, still in views/entries/sign_in.html.erb, can show the contents of that array to the site’s visitors so they can see who’s come by before, using the added lines shown in Example 4-8.

Example 4-8. Displaying existing users with a loop

<h1>Hello <%= @name %></h1> <%= form_tag action: 'sign_in' do %> <p>Enter your name: <%= text_field_tag 'visitor_name', @name %></p> <%= submit_tag 'Sign in' %> <% end %> <p>Previous visitors:</p> <ul> <% @entries.each do |entry| %> <li><%= entry.name %></li> <% end %> </ul>

The loop here iterates over the @entries array, running as many times as there are entries in @entries. @entries, of course, holds the list of names previously entered, pulled from the database by the model that was called by the controller in Example 4-7. For each entry, the view adds a list item containing the name value, referenced here as entry.name. The result, depending on exactly what names you entered, will look something like Figure 4-5.

It’s a lot of steps, yes, but fortunately you’ll be able to skip a lot of them as you move deeper into Rails. Building this guestbook didn’t look very much like the “complex-application-in-five-minutes” demonstrations that Rails promoters like to show off, but now you should understand what’s going on underneath the magic. After the apprenticeship, the next chapter will get into some journeyman fun. Also, after refreshing the page, look in the logs, and you’ll see that Rails is actually making a SQL call to populate the @entry array:

Entry Load (0.4ms) SELECT "entries".* FROM "entries"

This is from the @entries = Entry.all line we added to our controller earlier.

Figure 4-5. The guestbook application, now displaying the names of past visitors

Finding Data with ActiveRecord

The find method and its relatives are common in Rails, usually in controllers. It’s constantly used as find(id) to retrieve a single record with a given id, while the similar all method retrieves an entire set of records. There are four basic ways to call find, and then a set of options that can apply to all of those uses. You can also give all of these commands a try in the Rails console before you use them in your code. You can enter the Rails console by typing rails c in your terminal window. We will talk more about the console in Chapter 11, but give it a try with the following finder methods and sample output.

id-

The

findmethod is frequently called with a singleid, as infind(id), but it can also be called with an array ofids, likefind(id1, id2, id3, …)in which casefindwill return an array of values. Finally, you can callfind([id1, id2])and retrieve everything withidvalues betweenid1andid2.2.2.2 :003 > Entry.find 1 Entry Load (0.2ms) SELECT "entries".* FROM "entries" WHERE "entries"."id" = ? LIMIT 1 [["id", 1]] => #<Entry id: 1, name: "Henry", created_at: "2015-10-03 21:48:02", updated_at: "2015-10-03 21:48:02">

all-

Calling the

allmethod—Entry.all, for example—will return all the matching values as an array.2.2.2 :001 > Entry.all Entry Load (0.7ms) SELECT "entries".* FROM "entries" => #<ActiveRecord::Relation [#<Entry id: 1, name: "Henry", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:31", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:31">, #<Entry id: 2, name: "Rhoda", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:43", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:43">, #<Entry id: 3, name: "Allen", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:47", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:47">, #<Entry id: 4, name: "Mary", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:51", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:51">, #<Entry id: 5, name: "Pollie", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55">]>

first-

Calling

first—Entry.first, for example—will return the first matching value only. If you want this to raise an error if no matching record is found, add an exclamation point, asfirst!.2.2.2 :002 > Entry.first Entry Load (0.2ms) SELECT "entries".* FROM "entries" ORDER BY "entries"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 => #<Entry id: 1, name: "Henry", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:31", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:31">

last-

Calling

last—Entry.last, for example—will return the last matching value only. Just as withfirst, if you want this to raise an error if no matching record is found, add an exclamation point, aslast!.2.2.2 :003 > Entry.last Entry Load (0.2ms) SELECT "entries".* FROM "entries" ORDER BY "entries"."id" DESC LIMIT 1 => #<Entry id: 5, name: "Pollie", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55">

The options, which have evolved into chainable methods, give you much more control over what is queried and which values are returned. All of them actually modify the SQL statements used to query the database and can accept SQL syntax, but you don’t need to know SQL to use most of them. This list of options is sorted by your likely order of needing them:

where-

The

wheremethod lets you limit which records are returned. If, for example, you set:2.2.2 :004 > Entry.where(name: "Pollie") Entry Load (0.2ms) SELECT "entries".* FROM "entries" WHERE "entries"."name" = ? [["name", "Pollie"]] => #<ActiveRecord::Relation [#<Entry id: 5, name: "Pollie", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55">]>

then you would only see records where the

namehas a value ofPollie. order-

The

ordermethod lets you choose the order in which records are returned, though if you’re usingfirstorlastit will also determine which record you’ll see as first or last. The simplest way to use this is with a field name or comma-separated list of field names:2.2.2 :005 > Entry.order(:name) Entry Load (0.3ms) SELECT "entries".* FROM "entries" ORDER BY "entries"."name" ASC => #<ActiveRecord::Relation [#<Entry id: 3, name: "Allen", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:47", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:47">, #<Entry id: 1, name: "Henry", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:31", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:31">, #<Entry id: 4, name: "Mary", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:51", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:51">, #<Entry id: 5, name: "Pollie", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55">, #<Entry id: 2, name: "Rhoda", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:43", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:43">]>

By default, the

orderwill sort in ascending order, so the option just shown would sort by:namevalues in ascending order. We might also pass in a second sort field value:2.2.2 :005 > Entry.order(:name, :city)

Using

:cityas a second sort field would first sort by:name, then by:city. If you want to sort a field in descending order, just putdescafter the field name:2.2.2 :014 > Entry.order(name: "desc")

This will return the names sorted in descending order.

limit-

The

limitoption lets you specify how many records are returned. If you wrote:2.2.2 :016 > Entry.limit 3 Entry Load (0.2ms) SELECT "entries".* FROM "entries" LIMIT 3 => #<ActiveRecord::Relation [#<Entry id: 1, name: "Henry", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:31", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:31">, #<Entry id: 2, name: "Rhoda", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:43", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:43">, #<Entry id: 3, name: "Allen", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:47", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:47">]>

you receive only the first three records back. (You’ll probably want to specify

orderto ensure that they’re the ones you want.) offset-

The

offsetoption lets you specify a starting point from which records should be returned. If, for instance, you wanted to retrieve the next three records after a set you’d retrieved withlimit, you could specify:2.2.2 :017 > Entry.limit(3).offset(2) Entry Load (0.2ms) SELECT "entries".* FROM "entries" LIMIT 3 OFFSET 2 => #<ActiveRecord::Relation [#<Entry id: 3, name: "Allen", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:47", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:47">, #<Entry id: 4, name: "Mary", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:51", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:51">, #<Entry id: 5, name: "Pollie", created_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55", updated_at: "2015-10-03 22:07:55">]>

readonly-

The

readonlyoption retrieves records so that you can read them, but cannot make any changes. group-

The

groupoption lets you specify a field that the results should group on, like theSQL GROUP BYclause. lock-

locklets you test for locked rows. joins,include,select, andfrom-

These options let you specify components of the SQL query more precisely. You may need them as you delve into complex data structures, but you can ignore them at first.

Rails also offers dynamic finders, which are methods it automatically supports based on the names of the fields in the database. If you have a given_name field, for example, you can call find_by_given_name(name) to get the first record with the specified name, or find_all_by_given_name(name) to get all records with the specified name. These are a little slower than the regular find method but may be more readable.

Note

Rails also offers an elegant way to create more readable queries with scopes, which you should explore after you’ve found your way around.

Test Your Knowledge

Quiz

-

Where would you put code to which you want all of your controllers to have access?

-

How do the default routes decide which requests to send to your controller?

-

What does the

changemethod do in a migration? -

What three steps does the

createmethod combine? -

How do you test to find out whether a submitted field is blank?

-

How can you retrieve all of the values for a given object?

-

How can you find a set of values that match a certain condition?

-

How can you retrieve just the first item of a set?

Answers

-

Code in the

ApplicationControllerclass, stored at app/controllers/application_controller.rb, is available to all of the controllers in the project. -

The default routes assume that the controller name follows the first slash within the URL, that the controller action follows the second slash, and that the ID value follows the third slash. If there’s a dot (

.) after the ID, then what follows the dot is considered the format requested. -

The

changemethod is called when Rails runs a migration. The code explains what to create moving forward, but Rails can also run it backward. It usually creates tables and fields. -

The

createmethod creates a new object, sets its properties to those specified in the parameters, and saves it to the database. -

You can test to see whether something is blank using an

ifstatement and theblank?method, as in:if @name.blank? then something to do if blank end

-

To get the first of a set, use

.first. You may need to set an:orderparameter to make sure that your understanding of “first” matches that of Rails.

Get Learning Rails 5 now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.