Generating HTML is often a major component of web applications. This chapter is concerned with Lift’s View First approach and use of CSS Selectors. Later chapters focus more specifically on form processing, REST web services, JavaScript, Ajax, and Comet.

Code for this chapter is at https://github.com/LiftCookbook/cookbook_html.

You can use the Scala REPL to run your CSS selectors.

Here’s an example where we test out a CSS selector that adds an href attribute to a link.

Start from within SBT and use the console command to get into the REPL:

> console [info] Starting scala interpreter... [info] Welcome to Scala version 2.9.1.final Type in expressions to have them evaluated. Type :help for more information.

scala>importnet.liftweb.util.Helpers._importnet.liftweb.util.Helpers._scala>valf="a [href]"#>"http://example.org"f:net.liftweb.util.CssSel=(Full(a[href]),Full(ElemSelector(a,Full(AttrSubNode(href)))))scala>valin=<a>clickme</a>in:scala.xml.Elem=<a>clickme</a>scala>f(in)res0:scala.xml.NodeSeq=NodeSeq(<ahref="http://example.org">clickme</a>)

The Helpers._ import brings in the CSS selector functionality, which we then exercise by creating a selector, f, calling it with a very simple template, in, and observing the result, res0.

CSS selector transforms are one of the distinguishing features of Lift. They succinctly describe a node in your template (lefthand side) and give a replacement (operation, the righthand side). They do take a little while to get used to, so being able to test them at the Scala REPL is useful.

It may help to know that prior to CSS selectors, Lift snippets were typically defined in terms

of a function that took a NodeSeq and returned a NodeSeq, often via a method called bind. Lift would take your template, which would be the input NodeSeq, apply the function, and return a new NodeSeq. You won’t see that usage so often anymore, but the principle is the same.

The CSS selector functionality in Lift gives you a CssSel function,

which is NodeSeq => NodeSeq. We exploit this in the previous example by constructing an input

NodeSeq (called in), then creating a CSS function (called f). Because we know that CssSel

is defined as a NodeSeq => NodeSeq, the natural way to execute the selector is to supply

the in as a parameter, and this gives us the answer, res0.

If you use an IDE that supports a worksheet, which both Eclipse and IntelliJ IDEA do, then you can also run transformations in a worksheet.

The syntax for selectors is best described in Simply Lift.

See Developing Using Eclipse and Developing Using IntelliJ IDEA for how to work with Eclipse and IntelliJ IDEA.

Use andThen rather than & to compose your selector expressions.

For example, suppose we want to replace <div id="foo"/> with

<div id="bar">bar content</div> but for some reason we need to

generate the bar div as a separate step in the selector expression:

sbt> console [info] Starting scala interpreter... [info] Welcome to Scala version 2.9.1.final (Java 1.7.0_05). Type in expressions to have them evaluated. Type :help for more information.

scala>importnet.liftweb.util.Helpers._importnet.liftweb.util.Helpers._scala>defrender="#foo"#><divid="bar"/>andThen"#bar *"#>"bar content"render:scala.xml.NodeSeq=>scala.xml.NodeSeqscala>render(<divid="foo"/>)res0:scala.xml.NodeSeq=NodeSeq(<divid="bar">barcontent</div>)

When using &, think of the CSS selectors as always applying to the

original template, no matter what other expressions you are combining.

This is because & is aggregating the selectors together before applying them. In contrast, andThen is

a method of all Scala functions that composes two functions together, with the first being

called before the second.

Compare the previous example if we change the andThen to

&:

scala>defrender="#foo"#><divid="bar"/>&"#bar *"#>"bar content"render:net.liftweb.util.CssSelscala>render(<divid="foo"/>)res1:scala.xml.NodeSeq=NodeSeq(<divid="bar"></div>)

The second expression will not match, as it is applied to the original

input of <div id="foo"/>—the selector of #bar won’t match on id=foo,

and so adds nothing to the results of render.

The Lift wiki page for CSS selectors also describes this use of andThen.

Use the @ CSS binding name selector. For example, given:

<metaname="keywords"content="words, here, please"/>

The following snippet code will update the value of the content attribute:

"@keywords [content]"#>"words, we, really, want"

The @ selector selects all elements with the given name. It’s useful in this case to change the <meta name="keyword"> tag, but you may also see it used elsewhere. For example, in an HTML form, you can select input fields such as <input name="address"> with "@address".

The [content] part is an example of a replacement rule that can follow a selector. That’s to say, it’s not specific to the @ selector and can be used with other selectors. In this example, it replaces the value of the attribute called “content.” If the meta tag had no “content” attribute, it would be added.

There are two other replacement rules useful for manipulating attributes:

-

[content!]to remove an attribute with a matching value. -

[content+]to append to the value.

Examples of these would be:

scala>importnet.liftweb.util.Helpers._importnet.liftweb.util.Helpers._scala>valin=<metaname="keywords"content="words, here, please"/>in:scala.xml.Elem=<metaname="keywords"content="words, here, please"></meta>scala>valremove="@keywords [content!]"#>"words, here, please"remove:net.liftweb.util.CssSel=CssBind(Full(@keywords[content!]),Full(NameSelector(keywords,Full(AttrRemoveSubNode(content)))))scala>remove(in)res0:scala.xml.NodeSeq=NodeSeq(<metaname="keywords"></meta>)

and:

scala>valadd="@keywords [content+]"#>", thank you"add:net.liftweb.util.CssSel=CssBind(Full(@keywords[content+]),Full(NameSelector(keywords,Full(AttrAppendSubNode(content)))))scala>add(in)res1:scala.xml.NodeSeq=NodeSeq(<metacontent="words, here, please, thank you"name="keywords"></meta>)

Although not directly relevant to meta tags, you should be aware that there is one convenient special case for appending to an attribute. If the attribute is class, a space is added together with your class value. As a demonstration of that, here’s an example of appending a class called btn-primary to a div:

scala>defrender="div [class+]"#>"btn-primary"render:net.liftweb.util.CssSelscala>render(<divclass="btn"/>)res0:scala.xml.NodeSeq=NodeSeq(<divclass="btn btn-primary"></div>)

The syntax for selectors is best described in Simply Lift.

See Testing and Debugging CSS Selectors for how to run selectors from the REPL.

Select the content of the title element and replace it with the

text you want:

"title *"#>"I am different"

Assuming you have a <title> tag in your template, this will

result in:

<title>I am different</title>

This example uses an element selector, which picks out tags in the HTML template and replaces the content. Notice that we are using "title *" to select the content of the title tag. If we had left off the *, the entire title tag would have been replaced with text.

As an alternative, it is also possible to set the page title from the contents of SiteMap,

meaning the title used will be the title you’ve assigned to the page in

the site map. To do that, make use of Menu.title in your template directly:

<titledata-lift="Menu.title"></title>

The Menu.title code appends to any existing text in the title.

This means the following will have the phrase "Site Title - " in the

title, followed by the page title:

<titledata-lift="Menu.title">Site Title -</title>

If you need more control, you can of course bind on <title> using a

regular snippet. This example uses a custom snippet to put the site

title after the page title:

<titledata-lift="MyTitle"></title>

objectMyTitle{defrender=<title><lift:Menu.title/>-SiteTitle</title>}

Notice that our snippet is returning another snippet, <lift:Menu.title/>. This is a perfectly normal thing to do in Lift, and snippet invocations returned from snippets will be processed by Lift as normal.

Snippet Not Found When Using HTML5 describes the different ways to reference a snippet, such as data-lift and <lift: ... />.

At the Assembla website, there’s more about SiteMap and the Menu snippets.

Put the markup in a snippet and include the snippet in your page or template.

For example, suppose we want to include the HTML5 Shiv (a.k.a. HTML5 Shim) JavaScript so we can use HTML5 elements with legacy IE browsers. To do that, our snippet would be:

packagecode.snippetimportscala.xml.UnparsedobjectHtml5Shiv{defrender=Unparsed("""<!--[if lt IE 9]><script src="http://html5shim.googlecode.com/svn/trunk/html5.js"></script><![endif]-->""")}

We would then reference the snippet in the <head> of a page, perhaps even in

all pages via templates-hidden/default.html:

<scriptdata-lift="Html5Shiv"></script>

The HTML5 parser used by Lift does not carry comments from the source through to the rendered page. If you just tried to paste the html5shim markup into your template you’d find it missing from the rendered page.

We deal with this by generating unparsed markup from a snippet. If you’re looking at

Unparsed and are worried, your instincts are correct. Normally, Lift would cause the

markup to be escaped, but in this case, we really do want

unparsed XML content (the comment tag) included in the output.

If you find you’re using IE conditional comments frequently, you may want to create a more general version of the snippet. For example:

packagecode.snippetimportxml.{NodeSeq,Unparsed}importnet.liftweb.http.SobjectIEOnly{privatedefcondition:String=S.attr("cond")openOr"IE"defrender(ns:NodeSeq):NodeSeq=Unparsed("<!--[if "+condition+"]>")++ns++Unparsed("<![endif]-->")}

It would be used like this:

<divdata-lift="IEOnly">A div just for IE</div>

and produces output like this:

<!--[if IE]><div>A div just for IE</div><![endif]-->

Notice that the condition test defaults to IE, but first tries to look for an attribute called cond. This allows you to write:

<divdata-lift="IEOnly?cond=lt+IE+9">You're using IE 8 or earlier</div>

The + symbol is the URL encoding for a space, resulting in:

<!--[if lt IE 9]><div>You're using IE 8 or earlier</div><![endif]-->

The IEOnly example is derived from a posting on the mailing list from Antonio Salazar Cardozo.

The html5shim project can be downloaded from its Google Code site.

Use the PassThru transform.

Suppose you have a snippet that performs a transform when some condition is met, but if the condition is not met, you want the snippet to return the original markup.

Starting with the original markup:

<h2>Pass Thru Example</h2><p>There's a 50:50 chance of seeing "Try again" or "Congratulations!":</p><divdata-lift="PassThruSnippet">Try again - this is the template content.</div>

We could leave it alone or change it with this snippet:

packagecode.snippetimportnet.liftweb.util.Helpers._importnet.liftweb.util.PassThruimportscala.util.Randomimportxml.TextclassPassThruSnippet{privatedeffiftyFifty=Random.nextBooleandefrender=if(fiftyFifty)"*"#>Text("Congratulations! The content was changed")elsePassThru}

PassThru is an identity function of type NodeSeq => NodeSeq. It returns the input it

is given:

objectPassThruextendsFunction1[NodeSeq,NodeSeq]{defapply(in:NodeSeq):NodeSeq=in}

A related example is ClearNodes, defined as:

objectClearNodesextendsFunction1[NodeSeq,NodeSeq]{defapply(in:NodeSeq):NodeSeq=NodeSeq.Empty}

The pattern of converting one NodeSeq to another is simple, but also powerful enough to get you out of most situations, as you can always arbitrarily rewrite the NodeSeq.

You’re using Lift with the HTML5 parser and one of your snippets is rendering with a “Class Not

Found” error. It even happens for <lift:HelloWorld.howdy />.

Switch to the designer-friendly snippet invocation mechanism. For example:

<divdata-lift="HellowWorld.howdy"></div>

In this Cookbook, we use the HTML5 parser, which is set in Boot.scala:

// Use HTML5 for renderingLiftRules.htmlProperties.default.set((r:Req)=>newHtml5Properties(r.userAgent))

The HTML5 parser and the traditional Lift XHTML parser have different

behaviours. In particular, the HTML5 parser converts elements and attribute names to lowercase when looking up snippets. This means Lift would take <lift:HelloWorld.howdy /> and look for a class called helloworld rather than HelloWorld, which would be the cause of the “Class Not Found” error.

Switching to the designer-friendly mechanism is the solution here, and you gain validating HTML as a bonus.

There are three popular ways of referencing a snippet:

-

As an HTML5 data attribute:

data-lift="MySnippet" - This is the style we use in this book, and is valid HTML5 markup.

-

Using the

liftattribute, as in:lift="MySnippet" - This won’t strictly validate against HTML5, but you may see it used.

-

The XHTML namespace version:

<lift:MySnippet /> -

You’ll see the usage of this tag in templates declining because of the way it interacts with the HTML5 parser. However, it works just fine outside of a template, for example when embedding a snippet invocation in your server-side code (Setting the Page Title includes an example of this for

Menu.title).

The key differences between the XHTML and HTML5 parsers are outlined on the mailing list.

You’ve modified CSS or JavaScript in your application, but web browsers have cached your resources and are using the older versions. You’d like to avoid this browser caching.

Add the with-resource-id attribute to script or link tags:

<scriptdata-lift="with-resource-id"src="/myscript.js"type="text/javascript"></script>

The addition of this attribute will cause Lift to append a resource ID to

your src (or href), and as this resource ID changes each time Lift

starts, it defeats browser caching.

The resultant HTML might be:

<scriptsrc="/myscript.js?F619732897824GUCAAN=_"type="text/javascript"></script>

The random value that is appended to the resource is computed when your Lift application boots. This means it should be stable between releases of your application.

If you need some other behaviour from with-resource-id, you can assign

a new function of type String => String to

LiftRules.attachResourceId. The default implementation, shown previously,

takes the resource name, /myscript.js in the example, and returns the

resource name with an ID appended.

You can also wrap a number of tags inside a

<lift:with-resource-id>...<lift:with-resource-id> block. However,

avoid doing this in the <head> of your page, as the HTML5 parser will

move the tags to be outside of the head section.

Note that some proxies may choose not to cache resources with query parameters at all. If that impacts you, it’s possible to code a custom resource ID method to move the random resource ID out of the query parameter and into the path.

Here’s one approach to doing this. Rather than generate JavaScript and CSS links that look like /assets/style.css?F61973, we will generate /cache/F61973/assets/style.css. We then will need to tell Lift to take requests that look like this new format, and render the correct content for the request. The code for this is:

packagecode.libimportnet.liftweb.util._importnet.liftweb.http._objectCustomResourceId{definit():Unit={// The random number we're using to avoid cachingvalresourceId=Helpers.nextFuncName// Prefix with-resource-id links with "/cache/{resouceId}"LiftRules.attachResourceId=(path:String)=>{"/cache/"+resourceId+path}// Remove the cache/{resourceId} from the request if there is oneLiftRules.statelessRewrite.prepend(NamedPF("BrowserCacheAssist"){caseRewriteRequest(ParsePath("cache"::id::file,suffix,_,_),_,_)=>RewriteResponse(file,suffix)})}}

This would be initialised in Boot.scala:

CustomResourceId.init()

or you could just paste all the code into Boot.scala, if you prefer.

With the code in place, we can, for example, modify templates-hidden/default.html and add a resource ID class to jQuery:

<scriptid="jquery"data-lift="with-resource-id"src="/classpath/jquery.js"type="text/javascript"></script>

At runtime, this would be rendered in HTML as:

<scripttype="text/javascript"id="jquery"src="/cache/F352555437877UHCNRW/classpath/jquery.js"></script>

Most of the work for this is happening in the statelessRewrite, which is working at a low level inside Lift. The two parts to it are:

-

A

RewriteRequestthat is the pattern we’re matching on -

A

RewriteResponsethat is the result we want if the request matches

Looking at the RewriteRequest first, this expects three arguments: the path, which we care about, and then the method (e.g., GetRequest, PutRequest) and the HTTPRequest itself, neither of which concern us in this instance. In the path part, we’re matching on patterns that start with cache followed by something (we don’t care what), and then the rest of the path, represented by the name file. In that situation, we rewrite to the original path, which is just the file with the suffix, effectively removing the /cache/F352555437877UHCNRW part. This is the content that Lift will serve.

http://bit.ly/14BfNYJ shows the default implementation of attachResourceId.

Google’s “Optimize caching” notes are a good source of information about browser behaviour.

You can learn more about URL rewriting at the Lift wiki. Rewriting is used rarely, and only for special cases. Most problems that look like rewriting problems are better solved with a Menu Param.

You use a template for layout, but on one specific page you need to add

something to the <head> section.

Use the head snippet so Lift knows to merge the

contents with the <head> of your page. For example, suppose you have

the following contents in templates-hidden/default.html:

<htmllang="en"xmlns:lift="http://liftweb.net/"><head><metacharset="utf-8"></meta><titledata-lift="Menu.title">App:</title><scriptid="jquery"src="/classpath/jquery.js"type="text/javascript"></script><scriptid="json"src="/classpath/json.js"type="text/javascript"></script></head><body><divid="content">The main content will get bound here</div></body></html>

Also suppose you have index.html on which you want to include red-titles.css to change the style of just this page.

Do so by including the CSS in the part of the page that will get processed, and mark it with the head snippet:

<!DOCTYPE html><html><head><title>Special CSS</title></head><bodydata-lift-content-id="main"><divid="main"data-lift="surround?with=default;at=content"><linkdata-lift="head"rel="stylesheet"href="red-titles.css"type="text/css"/><h2>Hello</h2></div></body></html>

Note that this index.html page is validated HTML5, and will produce a

result with the custom CSS inside the <head> tag, something like this:

<!DOCTYPE html><htmllang="en"><head><metacharset="utf-8"><title>App: Special CSS</title><scripttype="text/javascript"src="/classpath/jquery.js"id="jquery"></script><scripttype="text/javascript"src="/classpath/json.js"id="json"></script><linkrel="stylesheet"href="red-titles.css"type="text/css"></head><body><divid="main"><h2>Hello</h2></div><scripttype="text/javascript"src="/ajax_request/liftAjax.js"></script><scripttype="text/javascript">// <![CDATA[varlift_page="F557573613430HI02U4";// ]]></script></body></html>

If you find your tags not appearing in the <head> section, check that

the HTML in your template and page is valid HTML5.

You can also use <lift:head>...</lift:head> to wrap a number of

expressions, and will see <head_merge>...</head_merge> used in the code

example as an alternative to <lift:head>.

Another variant you may see is class="lift:head", as an alternative to data-lift="head".

The head snippet is a built-in snippet, but otherwise no different from any snippet you might write. What the snippet does is emit a <head> block, containing the elements you want in the head. These can be <title>, <link>, <meta>, <style>, <script>, or <base> tags. How does this <head> block produced by the head snippet end up inside the main <head> section of the page? When Lift processes your template, it automatically merges all <head> tags into the main <head> section of the page.

You might suspect you can therefore put a plain old <head> section anywhere on your template. You can, but that would not necessarily be valid HTML5 markup.

There’s also tail, which works in a similar way, except anything marked with this snippet is moved to be just before the close of the body tag.

Move JavaScript to End of Page describes how to move JavaScript to the end of the page with the tail snippet.

The W3C HTML validator is a useful tool for tracking down HTML markup issues that may cause problems with content being moved into the head of your page.

In Boot.scala, add the following:

importnet.liftweb.util._importnet.liftweb.http._LiftRules.uriNotFound.prepend(NamedPF("404handler"){case(req,failure)=>NotFoundAsTemplate(ParsePath(List("404"),"html",true,false))})

The file src/main/webapp/404.html will now be served for requests to unknown resources.

The uriNotFound Lift rule needs to return a NotFound in reply to a

Req and Box[Failure]. This allows you to customise the

response based on the request and the type of failure.

There are three types of NotFound:

-

NotFoundAsTemplate -

Useful to invoke the Lift template processing

facilities from a

ParsePath -

NotFoundAsResponse -

Allows you to return a specific

LiftResponse -

NotFoundAsNode -

Wraps a

NodeSeqfor Lift to translate into a 404 response

In the example, we’re matching any not found situation, regardless of the request and the failure, and evaluating

this as a resource identified by ParsePath. The path we’ve used is /404.html.

In case you’re wondering, the last two true and false arguments to ParsePath

indicate the path we’ve given is absolute and doesn’t end in a

slash. ParsePath is a representation for a URI path, and exposing

if the path is absolute or ends in a slash are useful flags for matching on, but

in this case, they’re not relevant.

Be aware that 404 pages, when rendered this way, won’t have a location in the site map. That’s because we’ve not included the 404.html file in the site map, and we don’t have to, because we’re rendering via NotFoundAsTemplate rather than sending a redirect to /404.html. However, this means that if you display an error page using a template that contains Menu.builder or similar (as templates-hidden/default.html does), you’ll see “No Navigation Defined.” In that case, you’ll probably want to use a different template on your 404 page.

As an alternative, you could include the 404 page in your site map but make it hidden when the site map is displayed via the Menu.builder:

Menu.i("404")/"404">>Hidden

Catch Any Exception shows how to catch any exception thrown from your code.

Use LiftRules.responseTransformers to match against the response and

supply an alternative.

As an example, suppose we want to provide a custom page for 403 (“Forbidden”) statuses created in our Lift application. Further, suppose that this page might contain snippets so will need to pass through the Lift rendering flow.

To do this in Boot.scala, we define the LiftResponse we want to generate

and use the response when a 403 status is about to be produced by Lift:

defmy403:Box[LiftResponse]=for{session<-S.sessionreq<-S.requesttemplate=Templates("403"::Nil)response<-session.processTemplate(template,req,req.path,403)}yieldresponseLiftRules.responseTransformers.append{caserespifresp.toResponse.code==403=>my403openOrrespcaseresp=>resp}

The file src/main/webapp/403.html will now be served for requests that generate 403 status codes. Other non–403 responses are left untouched.

LiftRules.responseTransformers allows you to supply

LiftResponse => LiftResponse functions to change a response right at the end

of the HTTP processing cycle. This is a very general mechanism: in this

example, we are matching on a status code, but we could match on anything

exposed by LiftResponse.

In the recipe, we respond with a template, but you may find

situations where other kinds of responses make sense, such as an InMemoryResponse.

You could even simplify the example to just this:

LiftRules.responseTransformers.append{caserespifresp.toResponse.code==403=>RedirectResponse("/403.html")caseresp=>resp}

Note

In Lift 3, responseTransformers will be modified to be a partial function, meaning you’ll be able to leave off the final case resp => resp part of this example.

That redirect will work just fine, with the only downside that the HTTP status code sent back to the web browser won’t be a 403 code.

A more general approach, if you’re customising a number of pages, would be to define the status codes you want to customise, create a page for each, and then match only on those pages:

LiftRules.responseTransformers.append{caseCustomised(resp)=>respcaseresp=>resp}objectCustomised{// The pages we have customised: 403.html and 500.htmlvaldefinedPages=403::500::Nildefunapply(resp:LiftResponse):Option[LiftResponse]=definedPages.find(_==resp.toResponse.code).flatMap(toResponse)

deftoResponse(status:Int):Box[LiftResponse]=for{session<-S.sessionreq<-S.requesttemplate=Templates(status.toString::Nil)response<-session.processTemplate(template,req,req.path,status)}yieldresponse}

The convention in Customised is that we have an HTML file in src/main/webapp that matches

the status code we want to show, but of course you can change that by using a different

pattern in the argument to Templates.

One way to test the previous examples is to add the following to Boot.scala to make all requests to /secret return a 403:

valProtected=If(()=>false,()=>ForbiddenResponse("No!"))valentries=List(Menu.i("Home")/"index",Menu.i("secret")/"secret">>Protected,// rest of your site map here...)

If you request /secret, a 403 response will be triggered, which will match the response transformer showing you the contents of the 403.html template.

Custom 404 Page explains the built-in support for custom 404 messages.

Catch Any Exception shows how to catch any exception thrown from your code.

Include a NodeSeq containing a link in your notice:

S.error("checkPrivacyPolicy",<span>Seeour<ahref="/policy">privacypolicy</a></span>)

You might pair this with the following in your template:

<spandata-lift="Msg?id=checkPrivacyPolicy"></span>

You may be more familiar with the S.error(String) signature of Lift notices than the versions

that take a NodeSeq as an argument, but the String versions just convert the String argument

to a scala.xml.Text kind of NodeSeq.

Lift notices are described on the wiki.

You want a button or a link that, when clicked, will trigger a download in the browser rather than visiting a page.

Create a link using SHtml.link, provide a function to return a LiftResponse, and wrap the response in a ResponseShortcutException.

As an example, we will create a snippet that shows the user a poem and provides a link to download the poem as a text file. The template for this snippet will present each line of the poem separated by a <br>:

<h1>A poem</h1><divdata-lift="DownloadLink"><blockquote><spanclass="poem"><spanclass="line">line goes here</span><br/></span></blockquote><ahref="">download link here</a></div>

The snippet itself will render the poem and replace the download link with one that will send a response that the browser will interpret as a file to download:

packagecode.snippetimportnet.liftweb.util.Helpers._importnet.liftweb.http._importxml.TextclassDownloadLink{

valpoem="Roses are red,"::"Violets are blue,"::"Lift rocks!"::"And so do you."::Nildefrender=".poem"#>poem.map(line=>".line"#>line)&"a"#>downloadLinkdefdownloadLink=SHtml.link("/notused",()=>thrownewResponseShortcutException(poemTextFile),Text("Download"))defpoemTextFile:LiftResponse=InMemoryResponse(poem.mkString("\n").getBytes("UTF-8"),"Content-Type"->"text/plain; charset=utf8"::"Content-Disposition"->"attachment; filename=\"poem.txt\""::Nil,cookies=Nil,200)}

Recall that SHtml.link generates a link and executes a function you supply before following the link.

The trick here is that wrapping the LiftResponse in a ResponseShortcutException will indicate

to Lift that the response is complete, so the page being linked to (in this case, notused) won’t be processed. The browser is happy: it has a response to the link the user clicked on, and will render it how it wants to, which in this case will probably be by saving the file to disk.

SHtml.link works by generating a URL that Lift associates with the function you give it. On a page called downloadlink, the URL will look something like:

downloadlink?F845451240716XSXE3G=_#notused

When that link is followed, Lift looks up the function and executes it, before processing the linked-to resource. However, in this case, we are shortcutting the Lift pipeline by throwing this particular exception. This is caught by Lift, and the response wrapped by the exception is taken as the final response from the request.

This shortcutting is used by S.redirectTo via ResponseShortcutException.redirect. This companion object also defines shortcutResponse, which you can use like this:

importnet.liftweb.http.ResponseShortcutException._defdownloadLink=SHtml.link("/notused",()=>{S.notice("The file was downloaded")throwshortcutResponse(poemTextFile)},Text("Download"))

We’ve included an S.notice to highlight that throw shortcutResponse will process Lift notices when the page next loads, whereas throw new ResponseShortcutException does not. In this case, the notice will not appear when the user downloads the file, but it will be included the next time notices are shown, such as when the user navigates to another page. For many situations, the difference is immaterial.

This recipe has used Lift’s stateful features. You can see how useful it is to be able to close over state (the poem), and offer the data for download from memory. If you’ve created a report from a database, you can offer it as a download without having to regenerate the items from the database.

However, in other situations you might want to avoid holding this data as a function on a link. In that case, you’ll want to create a REST service that returns a LiftResponse.

Chapter 4 looks at REST-based services in Lift.

Streaming Content discusses InMemoryResponse and similar responses to return content to the browser.

For reports, the Apache POI project includes libraries for generating Excel files; and OpenCSV is a library for generating CSV files.

Supply a mock request to Lift’s MockWeb.testReq, and run your test in the context of the Req supplied by testReq.

The first step is to add Lift’s Test Kit as a dependency to your project in build.sbt:

libraryDependencies+="net.liftweb"%%"lift-testkit"%"2.5"%"test"

To demonstrate how to use testReq, we will test a function that detects a Google crawler. Google identifies

crawlers via various User-Agent header values, so the function we want to test would look like this:

packagecode.libimportnet.liftweb.http.ReqobjectRobotDetector{valbotNames="Googlebot"::"Mediapartners-Google"::"AdsBot-Google"::Nildefknown_?(ua:String)=botNames.exists(uacontains_)defgooglebot_?(r:Req):Boolean=r.header("User-Agent").exists(known_?)}

We have the list of magic botNames that Google sends as a user agent, and we define a check, known_?, that takes the user agent string and looks to see if any robot satisfies the condition of being contained in that user agent string.

The googlebot_? method is given a Lift Req object, and from this, we look up the header. This evaluates to a Box[String], as it’s possible there is no header. We find the answer by seeing if there exists in the Box a value that satisfies the known_? condition.

To test this, we create a user agent string, prepare a MockHttpServletRequest with the header, and use Lift’s MockWeb to turn the low-level request into a Lift Req for us to test with:

packagecode.libimportorg.specs2.mutable._importnet.liftweb.mocks.MockHttpServletRequestimportnet.liftweb.mockweb.MockWebclassSingleRobotDetectorSpecextendsSpecification{"Google Bot Detector"should{"spot a web crawler"in{valuserAgent="Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; Googlebot/2.1)"// Mock a request with the right header:valhttp=newMockHttpServletRequest()http.headers=Map("User-Agent"->List(userAgent))// Test with a Lift Req:MockWeb.testReq(http){r=>RobotDetector.googlebot_?(r)mustbeTrue}}}}

Running this from SBT with the test command would produce:

[info] SingleRobotDetectorSpec [info] [info] Google Bot Detector should [info] + spot a web crawler [info] [info] Total for specification SingleRobotDetectorSpec [info] Finished in 18 ms [info] 1 example, 0 failure, 0 error

Although MockWeb.testReq is handling the creation of a Req for us, the environment for that Req is supplied by the MockHttpServletRequest. To configure a request, create an instance of the mock and mutate the state of it as required before using it with testReq.

Aside from HTTP headers, you can set cookies, content type, query parameters, the HTTP method, authentication type, and the body. There are variations on the body assignment, which conveniently set the content type depending on the value you assign:

-

JValuewill use a content type ofapplication/json. -

NodeSeqwill usetext/xml(or you can supply an alternative). -

Stringusestext/plain(unless you supply an alternative). -

Array[Byte]does not set the content type.

In the example test shown earlier, it would be tedious to have to set up the same code repeatedly for different user agents. Specs2’s Data Table provides a compact way to run different example values through the same test:

packagecode.libimportorg.specs2._importmatcher._importnet.liftweb.mocks.MockHttpServletRequestimportnet.liftweb.mockweb.MockWebclassRobotDetectorSpecextendsSpecificationwithDataTables{defis="Can detect Google robots"^{"Bot?"||"User Agent"|true!!"Mozilla/5.0 (Googlebot/2.1)"|true!!"Googlebot-Video/1.0"|true!!"Mediapartners-Google"|true!!"AdsBot-Google"|false!!"Mozilla/5.0 (KHTML, like Gecko)"|>{(expectedResult,userAgent)=>{valhttp=newMockHttpServletRequest()http.headers=Map("User-Agent"->List(userAgent))MockWeb.testReq(http){r=>RobotDetector.googlebot_?(r)must_==expectedResult}}}}}

The core of this test is essentially unchanged: we create a mock, set the user agent, and check the result of googlebot_?. The difference is that Specs2 is providing a neat way to list

out the various scenarios and pipe them through a function.

The output from running this under SBT would be:

[info] Can detect Google robots [info] + Bot? | User Agent [info] true | Mozilla/5.0 (Googlebot/2.1) [info] true | Googlebot-Video/1.0 [info] true | Mediapartners-Google [info] true | AdsBot-Google [info] false | Mozilla/5.0 (KHTML, like Gecko) [info] [info] Total for specification RobotDetectorSpec [info] Finished in 1 ms [info] 1 example, 0 failure, 0 error

Although the expected value appears first in our table, there’s no requirement to put it first.

The Lift wiki discusses this topic and also other approaches such as testing with Selenium.

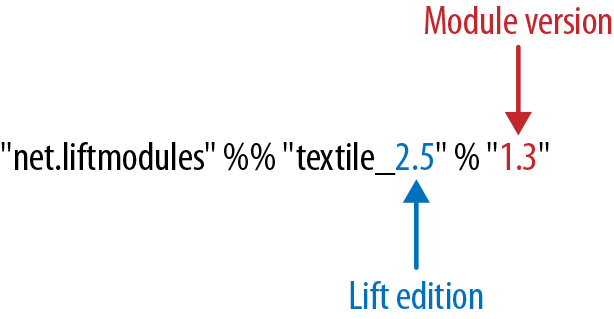

Install the Lift Textile module in your build.sbt file by adding the following to the list of dependencies:

"net.liftmodules"%%"textile_2.5"%"1.3"

You can then use the module to render Textile using the toHtml method.

For example, starting SBT after adding the module and running the SBT console command allows you to try out the module:

scala>importnet.liftmodules.textile._importnet.liftmodules.textile._scala>TextileParser.toHtml("""| h1. Hi!|| The module in "Lift":http://www.liftweb.net for turning Textile markup| into HTML is pretty easy to use.|| * As you can see.| * In this example.| """)res0:scala.xml.NodeSeq=NodeSeq(,<h1>Hi!</h1>,

,<p>The module in<ahref="http://www.liftweb.net">Lift</a>for turning Textile markup<br></br>into HTML is pretty easy to use.</p>, ,<ul><li>As you can see.</li><li>In this example.</li></ul>, , )

It’s a little easier to see the output if we pretty print it:

scala>valpp=newPrettyPrinter(width=35,step=2)pp:scala.xml.PrettyPrinter=scala.xml.PrettyPrinter@54c19de8scala>pp.formatNodes(res0)res1:String=

<h1>Hi!</h1><p>The module in<ahref="http://www.liftweb.net">Lift</a>for turning Textile markup<br></br>into HTML is pretty easy to use.</p><ul><li>As you can see.</li><li>In this example.</li></ul>

There’s nothing special code has to do to become a Lift module, although there are common conventions: they typically are packaged as net.liftmodules, but don’t have to be; they usually depend on a version of Lift; they sometimes use the hooks provided by LiftRules to provide a particular behaviour. Anyone can create and publish a Lift module, and anyone can contribute to existing modules. In the end, they are declared as dependencies in SBT, and pulled into your code just like any other dependency.

The dependency name is made up of two elements: the name and the “edition” of Lift that the module is compatible with, as shown in Figure 2-1. By “edition” we just mean the first part of the Lift version number. A “2.5” edition implies the module is compatible with any Lift release that starts “2.5.”

This structure has been adopted because modules have their own release cycle, independent of Lift. However, modules may also depend on certain features of Lift, and Lift may change APIs between major releases, hence the need to use part of the Lift version number to identify the module.

There’s no real specification of what Textile is, but there are references available that cover the typical kinds of markup to enter and what HTML you can expect to see.

The unit tests for the Textile module give you a good set of examples of what is supported.

Sharing Code in Modules describes how to create modules.

Get Lift Cookbook now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.