Mac OS X is an impressive technical achievement; many experts call it the best personal-computer operating system on earth. But beware its name.

The X is meant to be a Roman numeral, pronounced “10.” Don’t say “oh ess ex.” You’ll get funny looks in public.

In any case, Mac OS X Snow Leopard is the seventh major version of Apple’s Unix-based operating system. It’s got very little in common with the original Mac operating system, the one that saw Apple through the 1980s and 1990s. Apple dumped that in 2001, when CEO Steve Jobs decided it was time for a change. Apple had just spent too many years piling new features onto a software foundation originally poured in 1984. Programmers and customers complained of the “spaghetti code” the Mac OS had become.

On the other hand, underneath Mac OS X’s classy translucent desktop is Unix, the industrial-strength, rock-solid OS that drives many a Web site and university. It’s not new by any means; in fact, it’s decades old and has been polished by generations of programmers.

Mac OS X 10.6, affectionately known as Snow Leopard, is a strange beast, for a couple of reasons.

The first has to do with the Law of Software Upgrades, which has been in place since the dawn of personal computing. And that law says: “If you don’t add new features every year, nobody will upgrade, and you won’t make money.”

And so, to keep you upgrading, the world’s software companies pile on more features with every new version of their wares. Unfortunately, this can’t continue forever. Sooner or later, you wind up with a bloated, complex, incoherent mess of a program.

The shocker of Snow Leopard, though, is that upping the feature count wasn’t the point. In fact, Steve Jobs said, “We’re hitting Pause on new features.”

Instead, the point of Snow Leopard was refinement of the perfectly good operating system that Apple already had in the previous version, Mac OS X Leopard (10.5).

Refinement meant fixing hundreds of little annoyances, like the baffling error message that sometimes won’t let you eject a disk or a flash drive because it’s “busy.” Refinement meant making the whole thing faster, replacing substantial chunks of its plumbing—including rewriting the Finder from scratch—to be more modern and streamlined. Refinement also meant making Snow Leopard smaller—if you can believe it, half the size of the previous Mac OS X, saving you at least 6 gigabytes of hard drive space right off the bat.

As though to hammer home the point, Apple priced Snow Leopard at $30, about $100 less than its usual new-version Mac OS X price.

So wait. Apple’s not adding any new features? It’s spending all its time on polish, optimization, and making things work better? Has Steve Jobs gone completely nuts?

If so, be grateful. Snow Leopard builds beautifully on the successes of previous Mac OS X versions. You still don’t have to worry about viruses, spyware, or service pack releases that take up a Saturday afternoon to install and fine-tune. And you still enjoy stability that would make the you of 1999 positively drool.

But as it turns out, not all of Apple’s programmers got the “no new features” memo. As you’ll see in this book, there are hundreds of tiny new features and options. Maybe there’s a blurry line between “new feature” and “refinement of an existing feature,” but whatever; there are tons of enhancements.

A few of the big-ticket items:

It’s faster. Not everything is faster, but wherever Apple put effort into speeding things up, you feel it.

As noted above, the Finder—the desktop, where you manage your files, folders, and disks—was rewritten from scratch in Mac OS X’s native language; you’ll feel the zippiness right away. Startup and shutdown are faster. Mail and Safari open faster. Time Machine backups are faster. And installation is faster (and many steps simpler).

It’s better organized. Features like Exposé and stacks (pop-up Dock folders) have been redesigned to make more sense and reduce scrolling.

It talks to Exchange corporate computers. Just by entering your name and password for your company’s network, you make your Mac part of a Microsoft Exchange system. That is, your corporate email shows up in Mac OS X’s Mail program, the corporate directory shows up in Address Book, and your company calendar shows up in iCal—right alongside your own personal mail, addresses, and appointments.

It’s better for laptops. The Mac now adjusts its own clock when you travel, just like a cellphone. The menu of nearby wireless hot spots now shows the signal strength for each. Three- and four-finger trackpad “gestures” now work on even the oldest multitouch Mac laptops.

QuickTime Player is new. The Mac’s built-in movie player is brand new. It features a very cool frameless “screen,” plus a Trim command and one-click uploading to YouTube, MobileMe, or iTunes (for loading onto an iPod or iPhone). The new Player can even make audio recordings, video recordings, and—a first for a mainstream operating system—even screen recordings, so you can create how-to videos for your less-gifted relatives and friends.

It has major new text-editing features. Mac OS X’s system-wide spelling and grammar checker is joined this time around by a typing-expansion feature. You can create your own abbreviations that, when typed, expand to a word, phrase, or even a blurb of canned text many paragraphs long. It’s great for autofixing typos, of course, but also great for answering the same questions by email over and over.

Services are reborn. Services, a strange little menu of miscellaneous commands, has been in the Application menus for years now, baffling almost everyone. In Snow Leopard, they’ve been completely reborn. They now appear only when they’ll actually do something. Better yet, creating your own system-wide Services commands is a piece of cake, as Chapter 7 makes clear. You can also assign any keystroke you like to them. So for the first time in Macintosh history, you have a built-in means of opening favorite programs from the keyboard: Control-S for Safari, Control-W for Word, and so on.

Improved navigation for blind people. One feature turns your laptop’s trackpad into a touchable map of the screen; the Mac speaks each onscreen element as you touch it. In general, VoiceOver (as the talking-screen feature is called) has been given an enormous expansion/overhaul.

By way of a printed guide to Mac OS X, Apple provides only a flimsy “getting started” booklet. To find your way around, you’re expected to use Apple’s online help system. And as you’ll quickly discover, these help pages are tersely written, offer very little technical depth, lack useful examples, and provide no tutorials whatsoever. You can’t even mark your place, underline, or read it in the bathroom.

The purpose of this book, then, is to serve as the manual that should have accompanied Mac OS X—version 10.6 in particular.

Mac OS X Snow Leopard: The Missing Manual is designed to accommodate readers at every technical level. The primary discussions are written for advanced-beginner or intermediate Mac fans. But if you’re a Mac first-timer, miniature sidebar articles called Up To Speed provide the introductory information you need to understand the topic at hand. If you’re a Mac veteran, on the other hand, keep your eye out for similar shaded boxes called Power Users’ Clinic. They offer more technical tips, tricks, and shortcuts.

When you write a book like this, you do a lot of soul-searching about how much stuff to cover. Of course, a thinner book, or at least a thinner-looking one, is always preferable; plenty of readers are intimidated by a book that dwarfs the Tokyo White Pages.

On the other hand, Apple keeps adding features and rarely takes them away. So if this book is to remain true to its goal—serving as the best possible source of information about every aspect of Mac OS X—it isn’t going to get any thinner.

Even so, some chapters come with free downloadable appendixes—PDF documents, available on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com—that go into further detail on some of the tweakiest features. (You’ll see references to them sprinkled throughout the book.)

Maybe this idea will save a few trees—and a few back muscles when you try to pick this book up.

When your job is to write a new edition of a computer book, and you hear about a “no new features” mantra, you can’t help but be delighted. That should make the job easy, right? But in this case—wow, would you be wrong.

There may be very few big-ticket changes, but the number of tiny changes runs into the hundreds! Undocumented, tweaky little changes. For example:

The menu bar can now show the date, not just the day of the week. When you’re running Windows on your Mac, you can now open the files on the Macintosh “side” without having to restart. Icons can now be 512 pixels square—that’s huge—turning any desktop window into a light table for photos. There’s now a Put Back command in the Trash, which flings a discarded item right back into the folder it came from, even weeks later. You can page through a PDF document or watch a movie right on a file’s icon. Buggy plug-ins (Flash and so on) no longer crash the Safari Web browser; you just get an empty rectangle where they would have appeared. Video chats in iChat have much smaller connection-speed requirements. And on and on and on.

Not all of the changes will thrill everyone, though. Snow Leopard runs only on Macs with Intel processors, meaning that pre-2006 Macs aren’t invited to the party. Here and there, long-standing features have disappeared, especially in QuickTime Player. Plenty of little non-Apple utility programs no longer work in Snow Leopard, especially browser plug-ins and shortcut menu add-ons. And some ancient file-management features, like invisible Type and Creator codes, are gone.

In any case, it’d be pointless to try to draw up a single, tidy list of every change in Snow Leopard. Instead, throughout this book, within the relevant discussions, you’ll be alerted to all those little changes in little blurbs labeled like this:

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: Little items like this one point out subtle changes from the previous version(s) of Mac OS X—a good change, a bad change, or just a change.

Mac OS X Snow Leopard: The Missing Manual is divided into six parts, each containing several chapters:

Part One, covers everything you see on the screen when you turn on a Mac OS X computer: the Dock, the Sidebar, Spotlight, Dashboard, Spaces, Exposé, Time Machine, icons, windows, menus, scroll bars, the Trash, aliases, the

menu, and so on.

menu, and so on.Part Two, is dedicated to the proposition that an operating system is little more than a launchpad for programs—the actual applications you use in your everyday work, such as email programs, Web browsers, word processors, graphics suites, and so on. These chapters describe how to work with applications in Mac OS X: how to launch them, switch among them, swap data between them, use them to create and open files, and control them using the AppleScript and Automator automation tools.

Part Three, is an item-by-item discussion of the individual software nuggets that make up this operating system—the 27 panels of System Preferences, and the 50 programs in your Applications and Utilities folders.

Part Four, treads in more advanced territory. Networking, file sharing, and screen sharing, are, of course, tasks Mac OS X was born to do. These chapters cover all of the above, plus the prodigious visual talents of Mac OS X (fonts, printing, graphics, handwriting recognition), its multimedia gifts (sound, speech, movies), and the Unix that lies beneath.

Part Five, covers all the Internet features of Mac OS X, including the Mail email program and the Safari Web browser/RSS reader; iChat for instant messaging and audio or video chats; Web sharing; Internet sharing; and Apple’s online MobileMe services (which include email accounts, secure file-backup features, Web hosting, and more). If you’re feeling particularly advanced, you’ll also find instructions on using Mac OS X’s Unix underpinnings for connecting to, and controlling, your Mac from across the wires—FTP, SSH, VPN, and so on.

Part Six. This book’s appendixes include a Windows-to-Mac dictionary (to help Windows refugees find the new locations of familiar features in Mac OS X); guidance in installing this operating system; a troubleshooting handbook; a list of resources for further study; and an extremely thorough master list of all the keyboard shortcuts in Mac OS X Snow Leopard.

Throughout this book, and throughout the Missing Manual series, you’ll find sentences like this one: “Open the System folder→Libraries→Fonts folder.” That’s shorthand for a much longer instruction that directs you to open three nested folders in sequence, like this: “On your hard drive, you’ll find a folder called System. Open that. Inside the System folder window is a folder called Libraries; double-click it to open it. Inside that folder is yet another one called Fonts. Double-click to open it, too.”

Similarly, this kind of arrow shorthand helps to simplify the business of choosing commands in menus, such as ![]() →Dock→Position on Left.

→Dock→Position on Left.

To get the most out of this book, visit www.missingmanuals.com. Click the “Missing CD-ROM” link—and then this book’s title—to reveal a neat, organized, chapter-by-chapter list of the shareware and freeware mentioned in this book.

The Web site also offers corrections and updates to the book. (To see them, click the book’s title, and then click View/Submit Errata.) In fact, please submit such corrections and updates yourself! In an effort to keep the book as up to date and accurate as possible, each time O’Reilly prints more copies of this book, I’ll make any confirmed corrections you’ve suggested. I’ll also note such changes on the Web site so that you can mark important corrections into your own copy of the book, if you like. And I’ll keep the book current as Apple releases more Mac OS X 10.6 updates.

To use this book, and indeed to use a Macintosh computer, you need to know a few basics. This book assumes you’re familiar with a few terms and concepts:

Clicking. This book gives you three kinds of instructions that require you to use the Mac’s mouse. To click means to point the arrow cursor at something on the screen and then—without moving the cursor—press and release the clicker button on the mouse (or your laptop trackpad). To double-click, of course, means to click twice in rapid succession, again without moving the cursor at all. And to drag means to move the cursor while holding down the button.

When you’re told to ⌘-click something, you click while pressing the ⌘ key (which is next to the space bar). Shift-clicking, Option-clicking, and Control-clicking work the same way—just click while pressing the corresponding key.

(There’s also right-clicking. But that important topic is described in depth on Notes on Right-Clicking.)

Menus. The menus are the words at the top of your screen:

, File, Edit, and so on. Click one to make a list of commands appear.

, File, Edit, and so on. Click one to make a list of commands appear.Some people click and release to open a menu and then, after reading the choices, click again on the one they want. Other people like to press the mouse button continuously after the initial click on the menu title, drag down the list to the desired command, and only then release the mouse button. Either method works fine.

Keyboard shortcuts. If you’re typing along in a burst of creative energy, it’s disruptive to have to grab the mouse to use a menu. That’s why many Mac fans prefer to trigger menu commands by pressing certain combinations on the keyboard. For example, in word processors, you can press ⌘-B to produce a boldface word. When you read an instruction like “press ⌘-B,” start by pressing the ⌘ key, then, while it’s down, type the letter B, and finally release both keys.

Tip

You know what’s really nice? The keystroke to open the Preferences dialog box in every Apple program—Mail, Safari, iMovie, iPhoto, TextEdit, Preview, and on and on—is always the same: ⌘-comma. Better yet, that standard is catching on with other software companies, too; Word, Excel, Entourage, and PowerPoint use the same keystroke, for example.

Icons. The colorful inch-tall pictures that appear in your various desktop folders are the graphic symbols that represent each program, disk, and document on your computer. If you click an icon one time, it darkens, indicating that you’ve just highlighted or selected it. Now you’re ready to manipulate it by using, for example, a menu command.

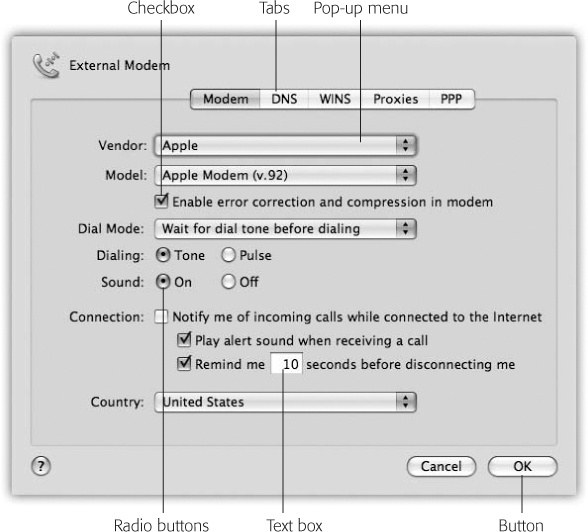

Checkboxes, radio buttons, tabs. See Figure 1 for a quick visual reference to the onscreen controls you’re most often asked to use.

A few more tips on mastering the Macintosh keyboard appear on The Macintosh Keyboard. Otherwise, if you’ve mastered this much information, you have all the technical background you need to enjoy Mac OS X Snow Leopard: The Missing Manual.

Get Mac OS X Snow Leopard: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.