The sounds of words carry meaning too, as big words for big movements demonstrate.

Steven Pinker, in his popular book on the nature of language, The Language Instinct 1 , encounters the frob-twiddle-tweak continuum as a way of talking about adjusting settings on computers or stereo equipment. The Jargon File, longtime glossary for hacker language, has the following under frobnicate ( http://www.catb.org/~esr/jargon/html/F/frobnicate.html ):

Usage: frob, twiddle, and tweak sometimes connote points along a continuum. ‘Frob’ connotes aimless manipulation; twiddle connotes gross manipulation, often a coarse search for a proper setting; tweak connotes fine-tuning. If someone is turning a knob on an oscilloscope, then if he’s carefully adjusting it, he is probably tweaking it; if he is just turning it but looking at the screen, he is probably twiddling it; but if he’s just doing it because turning a knob is fun, he’s frobbing it. 2

Why frob first? Frobbing is a coarse action, so it has to go with a big lump of a word. Twiddle is smaller, more delicate. And tweak, the finest adjustment of all, feels like a tiny word. It’s as if the actual sound of the word, as it’s spoken, carries meaning too.

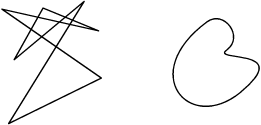

The two shapes in Figure 4-3 are a maluma and a takete. Take a look. Which is which?

Note

Don’t spoil the experiment for yourself by reading the next paragraph! When you try this out on others, you may want to cover up all but the figure itself.

If you’re like most people who have looked at shapes like these since the late 1920s, when Wolfgang Köhler devised the experiment, you said that the shape on the left is a “takete,” and the one on the right is a “maluma.” Just like “frob” and “tweak,” in which the words relate to the movements, “takete” has a spiky character and “maluma” feels round.

Words are multilayered in meaning, not just indices to some kind of meaning dictionary in our brains. Given the speed of speech, we need as many clues to meaning as we can get, to make understanding faster. Words that are just arbitrary noises would be wasteful. Clues to the meaning of speech can be packed into the intonation of a word, what other words are nearby, and the sound itself.

Brains are association machines, and communication makes full use of that fact to impart meaning.

In Figure 4-3, the more rounded shape is associated with big, full objects, objects that tend to have big resonant cavities, like drums, that make booming sounds if you hit them. Your mouth is big and hollow, resonant to say the word “maluma.” It rolls around your mouth.

On the other hand, a spiky shape is more like a snare drum or a crystal. It clatters and clicks. The corresponding sound is full of what are called plosives, sounds like t- and k- that involve popping air out.

That’s the association engine of the brain in action. The same goes for “frob” and “tweak.” The movement your mouth and tongue go through to say “frob” is broad and coarse like the frobbing action it communicates. You put your tongue along the base of your mouth and make a large cavity to make a big sound. To say “tweak” doesn’t just remind you of finely controlled movement, it really entails more finely controlled movement of the tongue and lips. Making the higher-pitched noise means making a smaller cavity in your mouth by pushing your tongue up, and the sound at the end is a delicate movement.

Test this by saying “frob,” “twiddle,” and “tweak” first thing in the morning, when you’re barely awake. Your muscle control isn’t as good as it usually is when you’re still half-asleep, so while you can say “frob” easily, saying “tweak” is pretty hard. It comes out more like “twur.” If you’re too impatient to wait until the morning, just imagine it is first thing in the morning—as you stretch say the words to yourself with a yawn in your voice. The difference is clear; frobbing works while you’re yawning, tweaking doesn’t.

Aside from denser meaning, these correlations between motor control (either moving your hands to control the stereo or saying the word) and the word itself may give some clues to what language was like before it was really language. Protolanguage, the system of communication before any kind of syntax or grammar, may have relied on these metaphors to impart meaning. 3 For humans now, language includes a sophisticated learning system in which, as children, we figure out what words mean what, but there are still throwbacks to the earlier time: onomatopoeic words are ones that sound like what they mean, like “boom” or “moo.” “Frob” and “tweak” may be similar to that, only drawing in bigness or roundness from the visual (for shapes) or motor (for mucking around with the stereo) parts of the brain.

Given the relationship between the sound of a word, due to its component phonemes and its feel (some kind of shared subjective experience), sound symbolism is one of the techniques used in branding. Naming consultants take into account the maluma and takete aspect of word meaning, not just dictionary meaning, and come up with names for products and companies on demand—for a price, of course. One of the factors that influenced the naming of the BlackBerry wireless email device was the b- sound at the beginning. According to the namers, it connotes reliability. 4

Pinker, S. (1994). The Language Instinct: The New Science of Language and Mind. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

The online hacker Jargon File, Version 4.1.0, July 2004 ( http://www.catb.org/~esr/jargon/index.html ).

This phenomenon is called phonetic symbolism, or phonesthesia. Some people have the perception of color when reading words or numbers, experiencing a phenomenon called synaesthesia. Ramachandran and Hubbard suggest that synaesthesia is how language started in the first place. See: Ramachandran, V. S., & Hubbard, E. M. (2001). Synaesthesia—a window into perception, thought and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8(12), 3–34. This can also be found online at http://psy.ucsd.edu/chip/pdf/Synaesthesia%20-%20JCS.pdf.

Begley, Sharon. “Blackberry and Sound Symbolism” ( http://www.stanford.edu/class/linguist34/Unit_08/blackberry.htm ), reprinted from the Wall Street Journal, August 26, 2002.

Naming consultancies were especially popular during the 1990s dotcom boom. Alex Frenkel took a look for Wired magazine in June 1997 in “Name-o-rama” ( http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/5.06/es_namemachine.html ).

Get Mind Hacks now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.