The length of a sentence isn’t what makes it hard to understand—it’s how long you have to wait for a phrase to be completed.

When you’re reading a sentence, you don’t understand it word by word, but rather phrase by phrase. Phrases are groups of words that can be bundled together, and they’re related by the rules of grammar. A noun phrase will include nouns and adjectives, and a verb phrase will include a verb and a noun, for example. These phrases are the building blocks of language, and we naturally chunk sentences into phrase blocks just as we chunk visual images into objects.

What this means is that we don’t treat every word individually as we hear it; we treat words as parts of phrases and have a buffer (a very short-term memory) that stores the words as they come in, until they can be allocated to a phrase. Sentences become cumbersome not if they’re long, but if they overrun the buffer required to parse them, and that depends on how long the individual phrases are.

Read the following sentence to yourself:

While Bob ate an apple was in the basket.

Did you have to read it a couple of times to get the meaning? It’s grammatically correct, but the commas have been left out to emphasize the problem with the sentence.

As you read about Bob, you add the words to an internal buffer to make up a phrase. On first reading, it looks as if the whole first half of the sentence is going to be your first self-contained phrase (in the case of the first, that’s “While Bob ate an apple”)—but you’re being led down the garden path. The sentence is constructed to dupe you. After the first phrase, you mentally add a comma and read the rest of the sentence...only to find out it makes no sense. Then you have to think about where the phrase boundary falls (aha, the comma is after “ate,” not “apple”!) and read the sentence again to reparse it. Note that you have to read again to break it into different phrases; you can’t just juggle the words around in your head.

Now try reading these sentences, which all have the same meaning and increase in complexity:

The cat caught the spider that caught the fly the old lady swallowed.

The fly swallowed by the old lady was caught by the spider caught by the cat.

The fly the spider the cat caught caught was swallowed by the old lady.

The first two sentences are hard to understand, but make some kind of sense. The last sentence is merely rearranged but makes no natural sense at all. (This is all assuming it makes some sort of sense for an old lady to be swallowing cats in the first place, which is patently absurd, but it turns out she swallowed a goat too, not to mention a horse, so we’ll let the cat pass without additional comment.)

Human languages have the special property of being recombinant. This means a sentence isn’t woven like a scarf, where if you want to add more detail you have to add it at the end. Sentences are more like Lego. The phrases can be broken up and combined with other sentences or popped open in the middle and more bricks added.

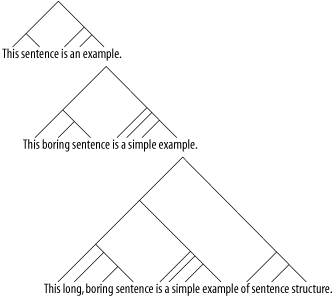

Have a look at these rather unimaginative examples:

The way sentences are understood is that they’re parsed into phrases. One type of phrase is a noun phrase, the object of the sentence. In “This sentence is an example,” the noun phrase is “this sentence.” For the second, it’s “this boring sentence.”

Once a noun phrase is fully assembled, it can be packaged up and properly understood by the rest of the brain. During the time you’re reading the sentence, however, the words sit in your verbal working memory—a kind of short-term buffer—until the phrase is finished.

Verb phrases work the same way. When your brain sees “is,” it knows there’s a verb phrase starting and holds the subsequent words in memory until that phrase has been closed off (with the word “example,” in the first sentence in the previous list). Similarly, the last part of the final sentence, “of sentence structure,” is a prepositional phrase, so it’s also self-contained. Phrase boundaries make sentences much easier to understand. Rather than the object of the third example sentence being three times more complex than the first (it’s three words: “long, boring sentence” versus one, “sentence”), it can be understood as the same object, but with modifiers.

It’s easier to see this if you look at the tree diagrams shown in Figure 4-4. A sentence takes on a treelike structure, for these simple examples, in which phrases are smaller trees within that. To understand a whole phrase, its individual tree has to join up. These sentences are all easy to understand because they’re composed of very small trees that are completed quickly.

We don’t use just grammatical rules to break sentences in chunks. One of the reasons the sentence about Bob was hard to understand was you expect, after seeing “Bob ate” to learn about what Bob ate. When you read “the apple,” it’s exactly what you expect to see, so you’re happy to assume it’s part of the same phrase. To find phrase boundaries, we check individual word meaning and likelihood of word order, continually revise the meaning of the sentence, and so on, all while the buffer is growing. But holding words in memory until phrases complete has its own problems, even apart from sentences that deliberately confuse you, which is where the old lady comes in.

Both of the first remarks on the old lady’s culinary habits require only one phrase to be held in buffer at a time. Think about what phrases are left incomplete at any given word. There’s no uncertainty over what any given “caught” or “by” words refer to: it’s always the next word. For instance, your brain read “The cat” (in the first sentence) and immediately said, “did what?” Fortunately the answer is the very next phrase: “caught the spider.” “OK,” says your brain, and pops that phrase out of working memory and gets on with figuring out the rest of the sentence.

The last example about the old lady is completely different. By the time your brain gets to the words “the cat,” three questions are left hanging. What about the cat? What about the spider? What about the fly? Those questions are answered in quick succession: the fly the old lady swallowed; the spider that caught the fly, and so on.

But because all of these questions are of the same type, the same kind of phrase, they clash in verbal working memory, and that’s the limit on sentence comprehension.

A characteristic of good speeches (or anything passed down in an oral tradition) is that they minimize the amount of working memory, or buffer, required to understand them. This doesn’t matter so much for written text, in which you can skip back and read the sentence again to figure it out; you have only one chance to hear and comprehend the spoken word, so you’d better get it right the first time around. That’s why speeches written down always look so simple.

That doesn’t mean you can ignore the buffer size for written language. If you want to make what you say, and what you write, easier to understand, consider the order in which you are giving information in a sentence. See if you can group together the elements that go together so as to reduce demand on the reader’s concentration. More people will get to the end of your prose with the energy to think about what you’ve said or do what you ask.

Caplan, D., & Waters, G. (1998). “Verbal Working Memory and Sentence Comprehension” ( http://cogprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00000623 ).

Steven Pinker discusses parse trees and working memory extensively in The Language Instinct. Pinker, S. (2000). The Language Instinct: The New Science of Language and Mind. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Get Mind Hacks now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.