As shown throughout this book, WinAmp and other MP3 players can be “costumed” with alternate interfaces called “skins.” Because skins are merely collections of bitmap images with pre-specified names and sizes, skins are not tied specifically to WinAmp, or even to Windows. While WinAmp is by far the most common place to find WinAmp skins in use, you’ll also find MP3 players for Mac OS, BeOS and Linux that wear WinAmp skins. In addition, there other MP3 players out there with even more radical interfaces (such as Sonique and K-Jöfol) that also wear skins. Note, however, that these players don’t wear WinAmp skins; see their sites for availability of skins for those players.

There are a number of large skin repositories on the Internet. The definitive collection is on WinAmp’s own site, at http://www.winamp.com/skins/. There you’ll find nearly 3,000 downloadable skins made by WinAmp users like yourself, categorized into groups like “Computer,” “Game,” “Stereo,” “Anime,” and even “Ugly” (and believe me, some of them deserve their place in that category). You’ll probably find the highest quality skins in the “Best Skins” category, a group that has been selected by WinAmp employees for their finesse and professional look. There are (at this writing) three other notable skins sites out there: http://www.1001winampskins.com is a site run by WinAmp fans for other fans (not connected to NullSoft), while http://www.skinz.org and http://www.customize.org offer skins for dozens of products, not just WinAmp (though their WinAmp skins collection is smaller than that of the other two sites).

Each skin collection arrives as a single zip file, and becomes

accessible to WinAmp simply by living in the skins directory

specified in the WinAmp preferences (which by default is in

C:\PROGRAM FILES\WINAMP\SKINS). If you have an

older version of WinAmp, you’ll need to unzip each collection

into a subdirectory of the skins directory. For example, a skin

archive called “Evo” might need to be decompressed in

C:\PROGRAM FILES\WINAMP\SKINS\EVO. However, if

you’re using WinAmp 2.04 or higher, you don’t need to

unzip the archive at all, since WinAmp is smart enough to unarchive

the files it needs on the fly (there is no noticeable performance

penalty for doing this).

Warning

If you do choose to decompress your skins, note that many skin authors carelessly zip up their collections without also zipping the parent directory, which means you can easily overwrite skin components of the same name if you don’t manually create an appropriate subdirectory first. If you use WinZip, a good way to do this is to right-click the zip archive and select “Extract To...” from the Context menu.

Once installed, skins can be activated by right-clicking anywhere in WinAmp’s interface and choosing Skin Selector from the context menu (tapping Alt+S will also bring up the Skin Selector). A panel will appear listing all installed skins. Single-clicking an entry will cause WinAmp’s interface to instantly adopt the new look. After donning a new skin, try enabling the WinAmp playlist and equalizer functions. Depending on how the author created the skin, these modules may or may not also take on the theme of the new skin. If skin components for these modules were not provided, they’ll appear with the default WinAmp look and feel.

Please note that some skins are distributed as shareware, rather than

as freeware. You should find a file called

readme.txt in each skin’s directory. If

the skin is shareware, it will say so in this file. If you like the

skin and decide to keep it, pay the author his or her due.

Note

If you have multiple operating systems installed on your computer, there’s no need to store the same skins collections multiple times. For example, since both BeOS and Linux can read Windows partitions, you may want to store all of your skins on your Windows partition and just create a symlink in your BeOS or Linux MP3 player directory called “skins” pointing to the location of your Windows skins directory. Of course you’ll need to make sure your Windows partition is mounted automatically at boot time if you want this technique to work transparently.

If you really want to call yourself a WinAmp pro, using other people’s skins won’t cut it—you’ve got to create a few of your own. While creating original skins can become tedious, time-consuming work—especially when you get into customizing regions and colors—the payoff can make the effort worth it. The only software you need is a good image editor, such as Adobe Photoshop, Paint Shop Pro, the GIMP (Linux and BeOS only), or something similar. You can even create skins in Microsoft Paint, though you’ll probably find Paint underpowered for the job.

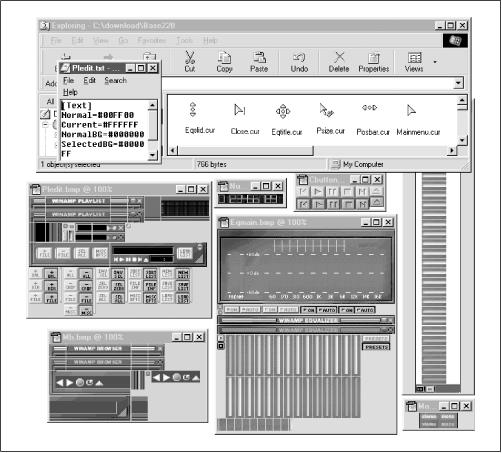

Next, you’ll need to understand the purpose of each of the

.bmp files in a skins directory. While you can

use any skin as a starting point, the definitive collection of

templates can be downloaded as

Base.<version>.zip from http://www.winamp.com/skins. You’ll also find

a skin-creation tutorial at that site. Unpack

base.zip and you’ll find three type of

files inside: .bmp files, which are the actual

graphics that will comprise your skin’s interface;

.cur files, which are standard Windows cursor

files to be activated when the user’s mouse hovers over

different parts of the interface (ignored when the skin is used by

another operating system); and .txt files, which

can be customized to specify the colors of non-graphical elements and

transparency behaviors.

Warning

You do not need to edit—or even include—a version of every single file in this directory. The behavior of elements for any files you don’t include will be supplied by WinAmp itself. In other words, the default WinAmp interface is always present behind your creation.

Open the various .bmp files in your image

editor, and the purpose of each will become immediately

obvious—you’ll see fragments of familiar interface

elements in each one, while each file’s purpose is also

declared by its file name (Figure 4.8). For

example, volume.bmp displays a column of colored

horizontal glowing strips, representing the colors of the volume

slider as you move it right and left.

Titlebar.bmp likewise shows all possible

incarnations of the WinAmp titlebar (e.g., as it appears when

maximized, when in zoom mode, and with and without the visualizer

enabled). All you have to do is edit these graphics to your liking,

taking care to preserve their dimensions and division lines

precisely. Because many of the elements, such as the fonts in

text.bmp, may appear very, very small,

you’ll probably want to get familiar with your image

editor’s zoom (magnifying glass) function.

Figure 4-8. Bitmaps, base configuration files, and Windows cursors, all with specific filenames that must not change

Because just creating new bitmaps for every possible interface

element in WinAmp can be a huge job, most skin creators call it a day

after finishing the graphics portion. If you really feel like

gettin’ jiggy wid’ it though, you’ll want to dig

into the .cur and .txt

collections as well.

The .cur files used by WinAmp are standard

Windows cursor files, and can be generated in any number of Windows

shareware programs designed for the purpose. You may want to look

into the excellent Microangelo (http://www.impactsoft.com) for some serious cursor

customization action. You should be able to determine the purpose of

each cursor file by its filename; for example,

eqslid.cur is the cursor that goes into effect

when the mouse is using the equalizer’s sliders, while

volbar.cur takes hold when adjusting

WinAmp’s volume.

The most technical aspect of skin creation (and again, this is

totally optional) may be the configuration of specific aspects of

WinAmp appearance and behavior from the text-based configuration

files region.txt,

viscolor.txt, and

pledit.txt.

The easiest to edit of these files is

pledit.txt, which lets you control the fonts and

font colors used in the playlist panel. All values are expressed in

hexadecimal, a format that will be familiar to most web developers.

If you need a good reference of hexadecimal color values, search the

web for “netscape colors” or “hexadecimal

colors.” You’ll find both web pages and applications that

will help you look these up easily. The format of

pledit.txt is simply:

[Text] Normal=#00FF00 Current=#FFFFFF NormalBG=#000000 SelectedBG=#000080 Font=Arial

Where Normal is the font color of most song

entries, Current is the color of the selected

track, NormalBG is the color of the playlist

background, and SelectedBG is the background color

for the selected track. If you specify fonts here, keep in mind that

your users may not have this font on their system. If the specified

font is not found, the default font will be used.

viscolor.txt lets you control the colors being

used by the WinAmp visualization module. Unlike

pledit.txt, colors here are expressed as RGB

triplets (one value each for the red, green, and blue color values).

You can use Windows’ built-in color manager (right-click on the

Desktop, choose Properties, select the Appearance tab, and click

Colors → Other) to determine RGB triplets. There are 24 lines in

this file, each of which corresponds to an audio level threshold.

Experimenting with this file is probably the best way to get a feel

for which entries take effect at which audio thresholds. If you want

to keep track of your changes, you can succeed each line with a

comment:

24,33,41, // This corresponds to mid-volume signals

Perhaps one of the most interesting interface controls you have as a

skin developer is afforded by region.txt, which

lets you use masks to “carve out” regions of WinAmp to be

considered invisible. By using a system of X,Y coordinates, you can

tell WinAmp only to draw specific sections of the interface, and to

leave the rest transparent. The results can be dramatic. Working with

region.txt is somewhat more complex than working

with the other text files. The principle here is that you specify the

shapes of polygons by telling WinAmp how many points each polygon

has, followed by a series of X,Y coordinates for each polygon. Since

WinAmp’s dimensions are 275×116 pixels, the X coordinate

values can range from

to 274, and the Y values can range from

to 115. In order to determine the exact coordinate points you need,

you’ll want to find the tool in your image editor that reports

the exact coordinates beneath the mouse cursor. (In Photoshop, pull

down Window → Show Info.) WinAmp simply draws all regions that

fall within the polygons you’ve defined and leaves the rest

invisible. Open region.txt in the base skin

collection and you’ll see lines like this:

;NumPoints=4 ;PointList=0,1, 275,1, 275,14, 0,14

Any line beginning with a ; is ignored, so to

enable any series of sample coordinates, just uncomment those lines,

save, and load the skin to see the effect. Of course, you’ll

probably want to define more than one polygon, but for ease of

development, just work on perfecting one polygon at a time (comment

out your perfected polygon and start a new one). Once all polygons

have been perfected, you’ll need to conjoin them all into a

single line, like this:

; NumPoints = 4, 4 ; In other words, define two squares ; PointList = 0,1, 275,1, 275,14, 0,14, 3,15, 272,15, 272,113, 3,113 ; The space between the two sets makes the coordinate series easier to read.

See the comments in region.txt for further

details. If you don’t want any transparency in your skin, just

delete region.txt or make sure all of its lines

are commented out.

Note

Mac users! MACAST supports a skin format that is incompatible with WinAmp skins. Fortunately, this also means that MACAST users are not limited to the size and shape constraints of WinAmp skins. If you do want to use WinAmp skins with MACAST, you can download a tool called SkinConverter from http://www.solsticetechnologies.com/skinconverter/ that will do the job nicely. If you use SoundJam, you’ll find a copy of SkinConverter in the SoundJam installation directory—just drag WinAmp skins onto the SkinConverter icon and they’ll be transformed into SoundJam skins and placed automatically in SoundJam’s skins folder, ready for use.

Get MP3: The Definitive Guide now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.