Programming is a skill that is acquired over several years of experience with a variety of programming languages and tasks. Key high-level abilities are algorithm design and its manifestation in structured programming. Key low-level abilities include familiarity with the syntactic constructs of the language, and knowledge of a variety of diagnostic methods for trouble-shooting a program which does not exhibit the expected behavior.

This section describes the internal structure of a program module and how to organize a multi-module program. Then it describes various kinds of error that arise during program development, what you can do to fix them and, better still, to avoid them in the first place.

The purpose of a program module is to bring logically related

definitions and functions together in order to facilitate reuse and

abstraction. Python modules are nothing more than individual .py files. For example, if you were working

with a particular corpus format, the functions to read and write the

format could be kept together. Constants used by both formats, such as

field separators, or a EXTN =

".inf" filename extension, could be shared. If the format

was updated, you would know that only one file needed to be changed.

Similarly, a module could contain code for creating and manipulating a

particular data structure such as syntax trees, or code for performing

a particular processing task such as plotting corpus

statistics.

When you start writing Python modules, it helps to have some

examples to emulate. You can locate the code for any NLTK module on

your system using the __file__

variable:

>>> nltk.metrics.distance.__file__ '/usr/lib/python2.5/site-packages/nltk/metrics/distance.pyc'

This returns the location of the compiled .pyc file for the module, and you’ll probably see a different location on your machine. The file that you will need to open is the corresponding .py source file, and this will be in the same directory as the .pyc file. Alternatively, you can view the latest version of this module on the Web at http://code.google.com/p/nltk/source/browse/trunk/nltk/nltk/metrics/distance.py.

Like every other NLTK module, distance.py begins with a group of comment

lines giving a one-line title of the module and identifying the

authors. (Since the code is distributed, it also includes the URL

where the code is available, a copyright statement, and license

information.) Next is the module-level docstring, a triple-quoted

multiline string containing information about the module that will be

printed when someone types help(nltk.metrics.distance).

# Natural Language Toolkit: Distance Metrics # # Copyright (C) 2001-2009 NLTK Project # Author: Edward Loper <edloper@gradient.cis.upenn.edu> # Steven Bird <sb@csse.unimelb.edu.au> # Tom Lippincott <tom@cs.columbia.edu> # URL: <http://www.nltk.org/> # For license information, see LICENSE.TXT # """ Distance Metrics. Compute the distance between two items (usually strings). As metrics, they must satisfy the following three requirements: 1. d(a, a) = 0 2. d(a, b) >= 0 3. d(a, c) <= d(a, b) + d(b, c) """

After this comes all the import statements required for the

module, then any global variables, followed by a series of function

definitions that make up most of the module. Other modules define

“classes,” the main building blocks of object-oriented programming,

which falls outside the scope of this book. (Most NLTK modules also

include a demo() function, which

can be used to see examples of the module in use.)

Note

Some module variables and functions are only used within the

module. These should have names beginning with an underscore, e.g.,

_helper(), since this will hide

the name. If another module imports this one, using the idiom:

from module import *, these names

will not be imported. You can optionally list the externally

accessible names of a module using a special built-in variable like

this: __all__ = ['edit_distance',

'jaccard_distance'].

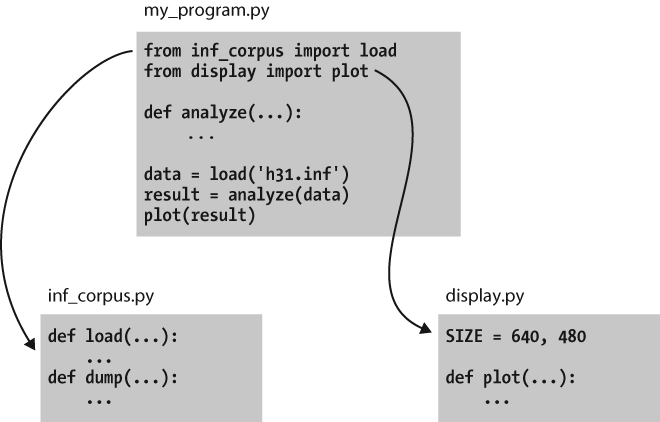

Some programs bring together a diverse range of tasks, such as loading data from a corpus, performing some analysis tasks on the data, then visualizing it. We may already have stable modules that take care of loading data and producing visualizations. Our work might involve coding up the analysis task, and just invoking functions from the existing modules. This scenario is depicted in Figure 4-2.

By dividing our work into several modules and using import statements to access functions

defined elsewhere, we can keep the individual modules simple and easy

to maintain. This approach will also result in a growing collection of

modules, and make it possible for us to build sophisticated systems

involving a hierarchy of modules. Designing such systems well is a

complex software engineering task, and beyond the scope of this

book.

Mastery of programming depends on having a variety of problem-solving skills to draw upon when the program doesn’t work as expected. Something as trivial as a misplaced symbol might cause the program to behave very differently. We call these “bugs” because they are tiny in comparison to the damage they can cause. They creep into our code unnoticed, and it’s only much later when we’re running the program on some new data that their presence is detected. Sometimes, fixing one bug only reveals another, and we get the distinct impression that the bug is on the move. The only reassurance we have is that bugs are spontaneous and not the fault of the programmer.

Flippancy aside, debugging code is hard because there are so many ways for it to be faulty. Our understanding of the input data, the algorithm, or even the programming language, may be at fault. Let’s look at examples of each of these.

First, the input data may contain some unexpected characters.

For example, WordNet synset names have the form tree.n.01, with three components separated

using periods. The NLTK WordNet module initially decomposed these

names using split('.'). However,

this method broke when someone tried to look up the word

PhD, which has the synset name ph.d..n.01, containing four periods instead

of the expected two. The solution was to use rsplit('.', 2) to do at most two splits,

using the rightmost instances of the period, and leaving the ph.d. string intact. Although several people

had tested the module before it was released, it was some weeks before

someone detected the problem (see http://code.google.com/p/nltk/issues/detail?id=297).

Second, a supplied function might not behave as expected. For example, while testing NLTK’s interface to WordNet, one of the authors noticed that no synsets had any antonyms defined, even though the underlying database provided a large quantity of antonym information. What looked like a bug in the WordNet interface turned out to be a misunderstanding about WordNet itself: antonyms are defined for lemmas, not for synsets. The only “bug” was a misunderstanding of the interface (see http://code.google.com/p/nltk/issues/detail?id=98).

Third, our understanding of Python’s semantics may be at fault.

It is easy to make the wrong assumption about the relative scope of

two operators. For example, "%s.%s.%02d" %

"ph.d.", "n", 1 produces a runtime error TypeError: not enough arguments for format

string. This is because the percent operator has higher

precedence than the comma operator. The fix is to add parentheses in

order to force the required scope. As another example, suppose we are

defining a function to collect all tokens of a text having a given

length. The function has parameters for the text and the word length,

and an extra parameter that allows the initial value of the result to

be given as a parameter:

>>> def find_words(text, wordlength, result=[]): ... for word in text: ... if len(word) == wordlength: ... result.append(word) ... return result >>> find_words(['omg', 'teh', 'lolcat', 'sitted', 'on', 'teh', 'mat'], 3)['omg', 'teh', 'teh', 'mat'] >>> find_words(['omg', 'teh', 'lolcat', 'sitted', 'on', 'teh', 'mat'], 2, ['ur'])

['ur', 'on'] >>> find_words(['omg', 'teh', 'lolcat', 'sitted', 'on', 'teh', 'mat'], 3)

['omg', 'teh', 'teh', 'mat', 'omg', 'teh', 'teh', 'mat']

The first time we call find_words() ![]() , we get all three-letter words as

expected. The second time we specify an initial value for the result,

a one-element list

, we get all three-letter words as

expected. The second time we specify an initial value for the result,

a one-element list ['ur'], and as

expected, the result has this word along with the other two-letter

word in our text. Now, the next time we call find_words() ![]() we use the same parameters as in

we use the same parameters as in ![]() , but we get a different result! Each

time we call

, but we get a different result! Each

time we call find_words() with no

third parameter, the result will simply extend the result of the

previous call, rather than start with the empty result list as

specified in the function definition. The program’s behavior is not as

expected because we incorrectly assumed that the default value was

created at the time the function was invoked. However, it is created

just once, at the time the Python interpreter loads the function. This

one list object is used whenever no explicit value is provided to the

function.

Since most code errors result from the programmer making

incorrect assumptions, the first thing to do when you detect a bug is

to check your assumptions. Localize the problem

by adding print statements to the

program, showing the value of important variables, and showing how far

the program has progressed.

If the program produced an “exception”—a runtime error—the interpreter will print a stack trace, pinpointing the location of program execution at the time of the error. If the program depends on input data, try to reduce this to the smallest size while still producing the error.

Once you have localized the problem to a particular function or to a line of code, you need to work out what is going wrong. It is often helpful to recreate the situation using the interactive command line. Define some variables, and then copy-paste the offending line of code into the session and see what happens. Check your understanding of the code by reading some documentation and examining other code samples that purport to do the same thing that you are trying to do. Try explaining your code to someone else, in case she can see where things are going wrong.

Python provides a debugger which allows you to monitor the execution of your program, specify line numbers where execution will stop (i.e., breakpoints), and step through sections of code and inspect the value of variables. You can invoke the debugger on your code as follows:

>>> import pdb

>>> import mymodule

>>> pdb.run('mymodule.myfunction()')It will present you with a prompt (Pdb) where you can type instructions to the

debugger. Type help to see the full

list of commands. Typing step (or

just s) will execute the current

line and stop. If the current line calls a function, it will enter the

function and stop at the first line. Typing next (or just n) is similar, but it stops execution at the

next line in the current function. The break (or b) command can be used to create or list

breakpoints. Type continue (or

c) to continue execution as far as

the next breakpoint. Type the name of any variable to inspect its

value.

We can use the Python debugger to locate the problem in our

find_words() function. Remember

that the problem arose the second time the function was called. We’ll

start by calling the function without using the debugger ![]() , using the smallest possible input. The

second time, we’ll call it with the debugger

, using the smallest possible input. The

second time, we’ll call it with the debugger ![]() .

.

>>> import pdb >>> find_words(['cat'], 3)['cat'] >>> pdb.run("find_words(['dog'], 3)")

> <string>(1)<module>() (Pdb) step --Call-- > <stdin>(1)find_words() (Pdb) args text = ['dog'] wordlength = 3 result = ['cat']

Here we typed just two commands into the debugger: step took us inside the function, and

args showed the values of its

arguments (or parameters). We see immediately that result has an initial value of ['cat'], and not the empty list as expected.

The debugger has helped us to localize the problem, prompting us to

check our understanding of Python functions.

In order to avoid some of the pain of debugging, it helps to

adopt some defensive programming habits. Instead of writing a 20-line

program and then testing it, build the program bottom-up out of small

pieces that are known to work. Each time you combine these pieces to

make a larger unit, test it carefully to see that it works as

expected. Consider adding assert

statements to your code, specifying properties of a variable, e.g.,

assert(isinstance(text, list)). If

the value of the text variable

later becomes a string when your code is used in some larger context,

this will raise an AssertionError and you will get

immediate notification of the problem.

Once you think you’ve found the bug, view your solution as a hypothesis. Try to predict the effect of your bugfix before re-running the program. If the bug isn’t fixed, don’t fall into the trap of blindly changing the code in the hope that it will magically start working again. Instead, for each change, try to articulate a hypothesis about what is wrong and why the change will fix the problem. Then undo the change if the problem was not resolved.

As you develop your program, extend its functionality, and fix

any bugs, it helps to maintain a suite of test cases. This is called

regression testing, since it is

meant to detect situations where the code “regresses”—where a change

to the code has an unintended side effect of breaking something that

used to work. Python provides a simple regression-testing framework in

the form of the doctest module.

This module searches a file of code or documentation for blocks of

text that look like an interactive Python session, of the form you

have already seen many times in this book. It executes the Python

commands it finds, and tests that their output matches the output

supplied in the original file. Whenever there is a mismatch, it

reports the expected and actual values. For details, please consult

the doctest documentation at

http://docs.python.org/library/doctest.html.

Apart from its value for regression testing, the doctest module is useful for ensuring that

your software documentation stays in sync with your code.

Perhaps the most important defensive programming strategy is to set out your code clearly, choose meaningful variable and function names, and simplify the code wherever possible by decomposing it into functions and modules with well-documented interfaces.

Get Natural Language Processing with Python now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.