Menus are often the only practical way to present a rich array of functionality without cluttering up the user interface. Whether appearing at the top of the window, or as a context menu accessed through the righthand mouse button, menus allow an application to show concisely which operations are available. An application’s usability can be further enhanced by making the most important operations available through toolbar buttons as well as menus.

The Windows Forms framework provides support for both menus and toolbars. Despite the fact that these two technologies serve similar roles—toolbar buttons often correspond directly to menu items—they are presented through two largely unrelated parts of the class library. However, as we will see later, it is possible to unify the way you handle events from them in your application.

In this chapter, we will first examine the support for menus. Then we will see how to create toolbars. Finally, we will see how events from both can be dealt with by a single set of event handlers.

The Windows Forms framework provides support for adding menus to your applications. It uses a single programming model both for normal window menus and for context menus. The model allows menus to be modified dynamically, or even combined, providing flexibility at runtime, and supports the ability to reuse and extend menu definitions.

We will start by examining the object model used for constructing menus. Then we will see how to attach them to a form. Next, we will look at how to add context menus. Finally, we will see how to reuse and extend your menu definitions by merging items from one menu into another, both in the context of MDI applications, and also when reusing forms through inheritance.

For your application to use menus, you must provide Windows Forms with a description of their structure and contents. You do this by building hierarchies of objects that represent menus and the items they contain. Although you will typically get Visual Studio .NET to do this for you, a sound understanding of the object model it uses is important to use menus effectively in your applications.

This object model revolves around the

Menu class, which is arguably misnamed, because it

represents a more abstract concept than its title suggests. It can

correspond to any element of a menu structure, and it is the base

class of all the other types in the menu object model. So while a

Menu object might represent a menu, it could just

represent a single item of a menu. (Perhaps

MenuElement would have been a more descriptive

name.) Representing menus and menu items with the same base type

seems a little strange at first, but it makes sense when you consider

that menus can be hierarchical. A menu item might well be a nested

menu, in which case, it makes sense for that menu item to be

represented by an object whose class derives from

Menu.

The main job of the Menu class is to represent the

structure of a menu. You can find out whether a particular

Menu object is a leaf item or an item with

children by examining its

IsParent property. If

IsParent is true, its child

items will be in a collection on the object’s

MenuItems property.

You will never use the Menu class directly. Its

constructor is protected, which means that to obtain a reference to a

Menu, you must instead create one of its

derivatives: MainMenu,

ContextMenu, or MenuItem.

The

MainMenu class

represents a form’s main menu, and

ContextMenu

represents a pop-up context menu. Every menu structure has one or the

other of these at its root, and you’ll see more

about how to use them later on. But everything else in the menu is

represented by

MenuItem objects.

Every line that the user sees in a menu (and every top-level menu in

a form’s main menu) is represented by a

MenuItem. A leaf item (i.e., a menu item that does

not lead to a submenu) is indicated by the fact that it has no

children. If the item leads to a submenu, the same object represents

both the item and the submenu.

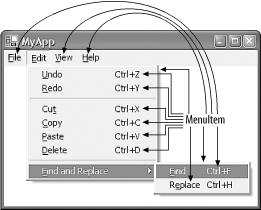

Figure 4-1 shows an example application with

a main menu. As you can see, a single MenuItem

object represents both the Edit caption and the menu associated with

it. Each entry in the menu (Undo, Redo, etc.) has its own

MenuItem object. The object that corresponds to

the Find and Replace item also represents the submenu (although the

entries in that submenu all have their own

MenuItem objects).

We’ll now look at how to go about building such hierarchies of objects to add menus to an application.

The easiest way to create a menu is to

use the Visual Studio .NET Forms Designer. It provides two

menu-related controls in the tool box: MainMenu

and ContextMenu. Each of these provides a visual

interface for editing the contents of a menu. Somewhat confusingly,

Visual Studio uses the same interface for both. This is a little

strange, because it means that the editor makes context menus look

like the form’s main menu. But this is just a

design-time anomaly—context menus are displayed correctly at

runtime.

As we have seen in previous chapters, anything done in the Forms

Designer simply ends up generating code. Menus are no exception, and

regardless of which kind of menu you create, the Forms Designer

generates the same kind of code. It will create a top-level menu

(either a MainMenu or a

ContextMenu), and then one

MenuItem

for each element of each menu. The C# code appears as follows:

this.mainMenu = new System.Windows.Forms.MainMenu(); this.menuFile = new System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem(); this.menuFileNew = new System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem(); this.menuFileOpen = new System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem(); this.menuFileClose = new System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem(); this.menuFileExit = new System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem();

The corresponding VB code is:

Me.mainMenu = New System.Windows.Forms.MainMenu() Me.menuFile = New System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem() Me.menuFileNew = New System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem() Me.menuFileOpen = New System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem() Me.menuFileClose = New System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem() Me.menuFileExit = New System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem()

Tip

By default, the Designer will choose unhelpful names for the menu

items, such as menuItem1,

menuItem2, etc. If you want your code to be

readable, it is a good idea to change each menu

item’s Name property to something

more meaningful in the Designer, as has been done in this example.

(The Name property is in the Design category of

the Properties window.)

Of course, creating a few menu items is

not enough to describe the menu fully—with the code as it

stands, Windows Forms will have no idea that

menuFile is an item of

mainMenu, or that menuFileNew,

menuFileOpen, and menuFileClose

are members of menuFile. So the designer also

generates code to establish the menu hierarchy.[15] In C#, the code looks

like this:

//

// mainMenu

//

this.mainMenu.MenuItems.AddRange(

new System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem[] {

this.menuFile,

this.menuEdit,

this.menuView,

this.menuHelp});

//

// menuFile

//

this.menuFile.Index = 0;

this.menuFile.MenuItems.AddRange(

new System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem[] {

this.menuFileNew,

this.menuFileOpen,

this.menuFileClose,

this.menuFileExit});In VB:

'mainMenu

'

Me.mainMenu.MenuItems.AddRange( _

New System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem() _

{Me.menuFile, _

Me.menuEdit, _

Me.menuView,

Me.menuHelp})

'

'menuFile

'

Me.menuFile.Index = 0

Me.menuFile.MenuItems.AddRange( _

New System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem() _

{Me.menuFileNew, _

Me.menuFileOpen, _

Me.menuFileClose, _

Me.menuFileExit})Note that the designer uses the same code for adding items to the

main menu as for adding items to the File submenu. This illustrates

why all the various menu classes derive from the

Menu base class—Menu

supplies the functionality common to all menu elements, such as the

ability to contain menu items.

A menu’s items are stored in the

MenuItems property,

whose type is the special-purpose collection class

Menu.MenuItemCollection. The code uses this

collection’s AddRange method to

add a list of MenuItem objects. Of course, because

each MenuItem inherits from

Menu, it has a MenuItems

property too, and can have further subitems added—this is how

nested menu structures are built.

The order in which you add menu items to a parent menu has no bearing

on the order in which they appear on screen. Their order is

controlled by the

Index property. This

property is an int or Integer,

and it is used to number child items sequentially starting from 0.

(The Designer does this automatically, and adjusts the

Index properties when you reorder items visually.)

The framework will also need to know what text should be displayed for each menu item, and whether it has any keyboard shortcut associated with it. So for each item, the Designer generates code like this in C#:

this.menuFileNew.Index = 0; this.menuFileNew.Shortcut = System.Windows.Forms.Shortcut.CtrlN; this.menuFileNew.Text = "&New...";

And code like this in VB:

Me.menuFileNew.Index = 0 Me.menuFileNew.Shortcut = System.Windows.Forms.Shortcut.CtrlN Me.menuFileNew.Text = "&New..."

As we have already seen, the Index property

determines the order in which menu items appear. The

Text property determines what text should be

displayed. (If you set this to a hyphen, the menu item will appear as a

separator—a dividing line between

menu items.) The

ampersand denotes something called an

accelerator; both this and the

Shortcut

property allow experienced users to use menus much more quickly than

would otherwise be possible.

Most Windows applications can be controlled from the keyboard as well as with the mouse. In fact, this is a requirement for earning the Designed for Windows logo. Accelerator keys and shortcut keys are two long-established mechanisms for making menus easier to use from the keyboard.

Menus can be navigated with the arrow keys, but with large menu structures, this rapidly becomes tiresome, so accelerator keys are also supported. These are keys that can be pressed to select a particular menu item without having to use the mouse or arrow keys. Each item in a menu can have a letter associated with it, and if the user presses that key while the menu is visible, the effect is the same as clicking on the item.

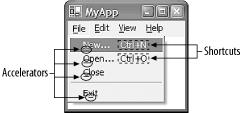

The previous code fragments illustrate how to choose an accelerator

key: in the Text property, we simply place an

ampersand in front of the relevant letter. So in this example, if the

user presses the N key while the File menu is open, the New menu item

will be selected. The user can find out what accelerator keys are

available by pressing the Alt key while the menu is open: the

accelerators will be underlined, as shown in Figure 4-2. (Older versions of Windows show the

accelerators at all times, even when Alt has not been pressed.)

Menu accelerators can make it easy for experienced users to use menus quickly without taking their hands off the keyboard. However, for very frequently used operations, keyboard shortcuts provide a more direct form of access.

Unlike menu accelerators, which can only be used while the relevant menu is visible, a shortcut key can be used at any time. In this example, the New menu item’s shortcut key is Ctrl-N. The user can press Ctrl-N without a menu visible, and it will be as if he had selected the New item from the File menu.

Shortcuts are assigned with the

Shortcut property on

the MenuItem class, and its value must be one of

the key combinations enumerated in the Shortcut

enumeration. This is a subset of all possible key presses; it

includes the function keys, with various combinations of modifier

keys (e.g., F12 or

CtrlShiftF3), and the alphanumeric keys with Ctrl

or Ctrl and Shift, (e.g., CtrlA,

CtrlShiftQ, Ctrl3). By default,

the shortcut will be displayed in the menu, as shown in Figure 4-2, although this can be disabled by

setting the ShowShortcut property to

false.

Shortcut keys only work because the Form class

knows about menus—when handling key presses, a form will offer

keys to the both the main menu and the context menu for that form.

This means that shortcuts only work properly for menus that have been

attached to a form (as described later on). You would usually not use

them on context menus that have been attached to specific controls.

So we know how to create hierarchical menu structures, and how to assign text, accelerators, and shortcut keys to menu items. But for all this to be of any use, we need to know when the user clicks on one of our menu items. So we will now look at the events raised by menus.

The entire point of adding menus to an application is so that users can ask the application to do something, such as save a file or perform a search. So as developers, we want our code to be notified whenever the user chooses an item from a menu. Menus therefore provide events to inform us of user input.

The most important menu event is

Click. This is

very similar to the Control

class’s Click event[16]—a MenuItem raises this event

when the user clicks on the menu item or performs an equivalent key

press (using either an accelerator or a shortcut key). It even has

the same signature as Control.Click:

EventHandler. If you double-click on a menu item

in the Designer, Visual Studio .NET will add a new method and attach

it to the menu item’s Click

event, as shown in C# in Example 4-1 and in VB in

Example 4-2.

Example 4-1. Menu Click handler in C#

private void InitializeComponent()

{

. . .

this.menuFileNew.Click +=

new System.EventHandler(this.menuFileNew_Click);

. . .

}

private void menuFileNew_Click(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

. . . handle click here

}Example 4-2. Menu click handler in VB

Friend WithEvents menuFileNew As System.Windows.Forms.MenuItem

Private Sub menuFileNew_Click(ByVal sender As System.Object, _

ByVal e As System.EventArgs) Handles menuFileNew.Click

. . . handle click here

End SubThe handler method’s first parameter is, as always,

the source of the event (the MenuItem object, in

this case). The second parameter is the usual placeholder and will

normally be EventArgs.Empty.

The MenuItem class also provides a

Popup event, which is

fired whenever a menu is about to be displayed. This provides a

useful opportunity to make sure that the state of all the items is up

to date (e.g., you can place ticks by certain menu items, as

described in the next section). The event occurs on the

MenuItem that represents the menu that is about to

appear. Its parent is not notified, and neither are the individual

items that make up the menu. For example, when the File menu in the

preceding examples is about to be displayed, the

Popup event would occur on the

menuFile object, not on the main menu, and not on

any of the File menu’s items.

You can also be notified when an item has been highlighted (i.e.,

when the mouse moves over it). That item’s

Select event is raised

when this happens. This event also occurs when the item is selected

with the arrow keys. The name Select is slightly

misleading. Selecting a menu item sounds like a fairly positive

operation by the user, but it typically indicates that the mouse has

simply moved over the item. The Click event is the

one raised when a user actively chooses an item.

If you are familiar with the old C++ MFC Library, you might be

expecting to see events for handling menu item state. In that

library, every time a menu item was displayed, an event was raised

asking whether the item should be enabled and whether it should have

a tick by it. In .NET, things are a little different—Windows

Forms exposes these features as properties on the

MenuItem object.

You will often want a menu item’s appearance to change according to the application’s state. For example, a menu item that turns something on or off (such as a status bar) can have a tick beside it to indicate that the feature is currently on. Some menu items may sometimes be unavailable and should be grayed out or even hidden. We will now see how to modify the appearance and behavior of menus at runtime to achieve this.

Each MenuItem has an

Enabled property. By

default, it is set to true, but when it is

false, the item will be grayed out and will not be

clickable. More drastically, you can set the

Visible property to false,

which will prevent the item from appearing at all. The

MenuItem class also provides a

Checked property. When

this is set, a tick will be displayed next to the menu item.

Tip

If you preferred the old MFC approach, in which you decided which

items should be ticked or disabled at the last minute, you can still

do this. Simply supply a Popup handler for the

menu and set the flags for each menu item in it. This approach can be

useful, because it guarantees that menu items are always up to date,

but an event-driven approach is no longer mandatory, so you can use

whichever is simpler for your particular application. Remember that

the Popup event is raised for the menu, not for

each of its items, so your code will not look quite the same as it

did with MFC—you will have a single handler setting the state

of all necessary items, rather than one handler per item.

So, we now know how to create menus, how to handle the events they generate, and how to modify the appearance of individual items. All that remains is to make sure these menus appear when and where we want them, which is the subject of the next section.

There are two ways in which a menu can appear. It can either be permanently visible at the top of a form, or it can be a so-called Context Menu that pops up when the user clicks the right (or alternate) mouse button. In either case, we simply associate a hierarchy of menu items with a form or a control.

The menu that appears at the top of a window is determined by the

Form class’s

Menu property. You can set this property

to a

MainMenu object

representing the root of a hierarchy of MenuItem

objects. The Forms Designer does this automatically when you add a

main menu to a form.

Setting a context menu is very similar, except context menus may be

assigned to any control, not just a form. This means that you can

provide different context menus for each control in a window. This is

done by setting the

ContextMenu property of

the control or form.

Remember that the Form class derives from

Control, so it is possible to set a context menu

for the whole form. Be aware though that when you add a context menu

to a form with the designer, Visual Studio .NET does not presume that

the menu should be attached to the form—for all it knows, you

might be planning to associate it with a control, so it leaves it

unattached. You must explicitly attach the menu either to the form or

to a control by setting the relevant object’s

ContextMenu property.

Be aware that keyboard shortcuts for a context menu will only work if the control that owns the menu is able to process keys. For a context menu attached to a form, this means that the shortcuts will work so long as the form is active, but for menus attached to a particular control on a form, the shortcuts will only work when that control has the focus. So it is not always useful to put shortcut keys on a context menu attached to a control, because the whole point of shortcut keys is that they can be used from any context. (The exception would be if your control can receive the focus and presents a nontrivial interactive user interface. For example, a text box provides clipboard shortcuts such as Ctrl-C for copy. In this case, it makes sense for the shortcuts only to be available when the control has the focus.)

Sometimes it is useful to know if a menu is currently being displayed

to avoid distracting or interrupting the user—it can be

annoying if an application pops up a notification dialog while you

are using a menu, because this causes the menu to be closed. If you

want to disable or defer certain operations while a menu is open, you

simply need to observe the Form

class’s

MenuStart and

MenuComplete events. These are fired just before a

menu receives the focus and just after it disappears. These events

are fired for the form’s context menu as well as for

its main menu. Unfortunately, the form does not raise these events

for a control-specific context menu, and although you could handle

such a menu’s Popup event, there

is unfortunately no corresponding event to tell you when it goes

away.

Many applications present several forms that all have similar but slightly different menus. This is particularly common when forms inheritance is in use (see Chapter 6). MDI applications often have a related requirement: a form may make subtle changes to its menu structure depending on which child window (if any) is active.

Unfortunately, we cannot exploit inheritance here as we would for

building a group of similar forms: whereas the structure and behavior

of a form is represented by a class definition, the structure and

behavior of a menu is defined by an object graph constructed at

runtime. All menus are made from a collection of objects that are

always of the same types (several MenuItem objects

and either one MainMenu or one

ContextMenu), so inheritance cannot help us here.

The good news is that the Menu class provides a

solution. It provides a method called

MergeMenu

that allows us to take an existing menu structure and extend or

modify it to create a new menu. The resulting menu will be the

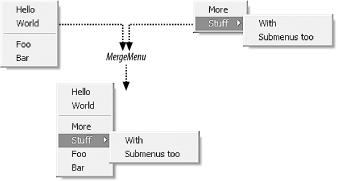

combination of the two menus, as illustrated in Figure 4-3.

Figure 4-3 illustrates the simplest way of using

menu merging—two menus are combined, and the result is a menu

containing all the items from each. The MergeMenu

method does a deep copy, so any submenus will also be duplicated.

This merging is easy to do—the following C# code (the VB code

is almost identical) shows how to create a new context menu by

merging the items from two other menus:

ContextMenu mergedMenu = new ContextMenu(); mergedMenu.MergeMenu(menuFirst); mergedMenu.MergeMenu(menuSecond);

But even this simple example raises an interesting question: how does

the framework decide the order in which to place the items in the

created menu? While it has not reordered the items from each

individual menu in Figure 4-3, it has decided to

insert the items from the second menu halfway through those of the

first menu. The framework determines how to interleave the

menus’ contents by looking at the

MergeOrder property on

each MenuItem. This property is an

int or Integer, and the

framework guarantees that when combining menus, it will merge items

in ascending MergeOrder order. So the reason the

framework decides to insert the second menu’s

contents halfway down becomes clear when we see the

MergeOrder property settings on the original

menus:[17]

this.menuHello.MergeOrder = 5; this.menuWorld.MergeOrder = 5; this.menuSeparator1.MergeOrder = 10; this.menuFoo.MergeOrder = 100; this.menuBar.MergeOrder = 100; this.menuMore.MergeOrder = 20; this.menuStuff.MergeOrder = 20;

The More and Stuff items in the second menu have a merge order of 20,

which means that they appear between the separator and the Foo entry,

which have orders of 10 and 100, respectively. You can choose

whatever values you like for a merge order, but using 0 for the items

you want to appear first, 100 for those you want to appear last, and

more or less evenly spaced values for those in between is a popular

choice. (The default MergeOrder is 0.)

The merging technique shown above is sufficient for many purposes, but you might need to do something a little more complex. For example, sometimes it is not enough simply to add new items to a menu—you may wish to remove items. Also, if you want to insert new items into a submenu instead of the top level menu, the naïve approach is insufficient: by default you will end up with two identically named submenus.

To support these more subtle merging techniques, the

MenuItem class provides a

MergeType property,

which controls the way an item is treated when it is merged. By

default, its value is MenuMerge.Add, meaning that

all items in the menu being merged will be added as new items.

You can set MergeType to

MenuMerge.Remove, which causes the corresponding

entry not to appear. You would use this value if the menu you are

modifying contains an entry you would like to remove.

Tip

You must set the MergeType property on both source

menus for this technique to work. If the new menu being merged into

the original menu attempts to remove an item, that attempt will be

ignored unless the original menu’s corresponding

item (the item with the same MergeOrder) is also

marked as MenuMerge.Remove.

So the

MergeType property really has two

meanings—on the original item it indicates the allowable

operations, and on the new item it indicates the operation being

requested. Unfortunately, not only is this overloading slightly

confusing, it is somewhat restrictive— there is no way to

create a menu item that allows both the MergeItem

and the Remove operations. Conflicts are also

dealt with a little inconsistently—if the original is

Add and the new is Remove, the

new item is ignored; if the original is Remove and

the new is MergeItem, the item is replaced!

Setting MergeType to

MenuMerge.Replace is similar to remove, except it

replaces the original item with the one in the menu being merged.

Finally, MergeType can be set to

MenuMerge.MergeItems. This value is used when you

wish to modify the contents of a submenu. Although you could modify a

submenu by replacing it entirely, MergeItems is

useful when you want to make only minor modifications. You use this

by supplying a MergeItems item corresponding to

the submenu item in the original menu, and then put child items

underneath it, using Add,

Remove, Replace, or

MergeItems as appropriate. For example, if you

wanted to add an item to a main menu’s File menu,

you would not replace the entire main menu, or even the entire File

menu. The following code (in C#) would suffice:

MenuItem mergingFileMenu = new MenuItem();

mergingFileMenu.MergeType = MenuMerge.MergeItems;

mergingFileMenu.Text = "&File";

MenuItem menuExtraFileItem = new MenuItem();

menuExtraFileItem.Text = "Ext&ra";

menuExtraFileItem.MergeOrder = 10;

MenuItem menuExtraFileSeparator = new MenuItem();

menuExtraFileSeparator.Text = "-";

menuExtraFileSeparator.MergeOrder = 10;

mergingFileMenu.MenuItems.AddRange(new MenuItem[] {

menuExtraFileItem,

menuExtraFileSeparator});

MainMenu mergingMainMenu = new MainMenu(new MenuItem[] {

mergingFileMenu });

mainMenu.MergeMenu(mergingMainMenu);This adds an item labeled Extra to the File menu, followed by a separator. So even though we are merging two main menus together, we are able to modify one of its submenus without having to replace that submenu wholesale. And although this may look like a lot of code to add a single item, it is rather less than would be required to reconstruct the whole menu. Furthermore, building a modified File menu from scratch presents code maintenance issues—if you want to change the basic File menu, you would also need to change all the places where you build a modified version. But if you use menu merging, any changes to the basic menu will automatically propagate to the modified versions.

Remember that this will only work if the original main

menu’s File menu item also has its

MergeType set to

MenuMerge.MergeItems; if it were set to the

default of MenuMerge.Add, you would end up with

two File submenus in the main menu.

If you build an MDI application, the framework can automatically take advantage of menu merging. The menus in such applications typically consist of two types of items: those that are associated with a document window and those that are a part of the main application frame. The set of available menu items is determined by whether a document window is active (and if there is more than one kind of document window, it will depend on which one is active).

The application-level menu items are those that should always be present and that make sense even if there are no open documents, such as items for file opening, document creation, or application configuration. Document-level menu items are those that only make sense in the context of a document, such as items for file closing or saving, editing operations, or view settings. MDI applications usually present just a single menu bar as part of the main application frame, but its contents change between being just the application-level items or the complete set, according to whether a document is active.

This seems like an ideal opportunity to use menu merging—the

application-level items could be placed into one

MainMenu, the document level items into a second

MainMenu, and these could be merged to create a

third. All that would need to be done would be to swap in the

appropriate merged or unmerged version according to whether a child

window is active. Indeed, this is exactly how MDI applications

usually work in .NET, but it turns out that Windows Forms can do the

menu merging automatically.

If you use the framework’s built-in support for MDI

applications (i.e., you establish the parent/child relationship with

the Form class’s

MdiParent or MdiChildren

properties), it will assume that the parent form’s

MainMenu contains the application-level menu

items, and that any child form’s

MainMenu contains document-level items. Whenever

an MDI child form is activated, the framework will automatically

merge its menu into the parent form’s menu. If all

MDI child windows are closed, it reverts to the original parent

form’s menu.

So using menu merging in MDI applications requires almost no effort.

The only thing you need to be careful about is setting the correct

MergeType—very

often a child window will want to add entries (such as for adding a

save and a close entry to the File menu) into an existing menu in the

parent. Both the parent and the child form’s main

menus will need to contain File submenus, which must both have the

same MergeOrder, and they must both have a

MergeType of

MenuMerge.MergeItems.

It is possible to define a form that derives from another form. We will be looking at the use of inheritance in detail in Chapter 6, but we will quickly examine the inheritance-related aspects of menu merging here.

When building an inherited form, the derived class will automatically acquire the base class’s menu. However, if you try to edit the menu in the derived class, the Forms Designer will prevent you, complaining that the menu is defined on the base class. To modify a menu on the derived form, you must use menu merging.

To modify the menu in the derived class, you must add a new

MainMenu component to the form. Place whatever

modifications you require in this menu. To merge this menu in with

the main menu requires a little code. Add the following C# code to

your constructor:

MainMenu mainMenu = new MainMenu(); mainMenu.MergeMenu(this.Menu); mainMenu.MergeMenu(mainMenuDerived); this.Menu = mainMenu;

The equivalent VB code is:

Dim mainMenu As New MainMenu() mainMenu.MergeMenu(Me.Menu) mainMenu.MergeMenu(mainMenuDerived) Me.Menu = mainMenu

This builds a new MainMenu object, which takes the

original menu and merges in mainMenuDerived (or

whatever you choose to call the MainMenu that you

added to your derived form). It then sets this merged menu as the new

main menu of the form.

The

standard appearance provided by the Windows Forms framework for menu

items is pretty basic—you get simple text, and you can

optionally annotate menu items with a tick (just set the

Checked property). If you want to draw your own

annotations, or otherwise provide richer visual information, the

framework lets you draw your own menu items. The use of GDI+ to

perform custom drawing is discussed in detail in Chapter 7, but here we will look at the menu-specific

aspects of owner drawing.

You can decide to do your own drawing on a per-item basis by setting

the MenuItem object’s

OwnerDraw property to

true. Unfortunately, it is an all or nothing

decision: if you ask the framework to let you draw a particular item,

you are required to manage the whole drawing process. First, you must

tell the framework the size of your menu item by

handling the

MeasureItem event;

otherwise, the item will default to having a height of 0 pixels. And

you must also handle the

DrawItem event, in

which you are responsible for drawing everything, including the text

of the menu. (Turning on OwnerDraw will prevent

Windows from drawing anything other than the menu background.)

Tip

Because owner drawing is a per-item decision, it is possible to have a single menu with a mixture of owner-drawn and system-drawn items.

You will receive the DrawItem event every

time the item needs redrawing. This happens when the menu appears,

directly after the MeasureItem event, but it also

happens again every time the mouse moves on or off the menu item, so

that you can highlight your item like Windows does for normal items.

Your event handler will be passed a

DrawItemEventArgs object, whose

State member indicates how the item should be

drawn. This field is of type DrawItemState, which

is a bit field, so it may indicate multiple styles simultaneously.

The flags that may be set are Selected (indicating

that the mouse is currently over the item),

NoAccelerator (indicating that accelerator keys

should not be displayed; this will normally be set unless the user is

operating the menu through the keyboard), and

Checked (indicating that a tick should be drawn by

the item).

Examples Example 4-3 and

Example 4-4 show a pair of event handlers for a very

simple owner-drawn menu. The item is always the same size because the

MeasureItem handler always returns the same width

and height. The DrawItem handler simply draws an

ellipse as the menu item, but it illustrates an important technique:

it checks the item’s state to see if it is selected,

and if so, it draws the menu background in the normal selected menu

item color, and draws the ellipse in the same color as selected text

in a menu would be drawn. Note the use of the

DrawBackground method of the

DrawItemEventArgs object to fill in the menu

background—it draws the background in the appropriate color

(i.e., SystemColors.Menu, unless the item is

selected, in which case it uses

SystemColors.Highlight). We call this whether the

item is in the selected state or not. You might think that this is

unnecessary because, as mentioned above, the framework draws the

background for us. Unfortunately it only does that when the menu is

first opened, so if we change the background when our item is

selected, we are required to put it back again when it is deselected.

Example 4-3. Simple owner-drawn menu item in C#

private void menuItem_MeasureItem(object sender,

System.Windows.Forms.MeasureItemEventArgs e)

{

e.ItemHeight = 17;

e.ItemWidth = 100;

}

private void menuItem_DrawItem(object sender,

System.Windows.Forms.DrawItemEventArgs e)

{

Graphics g = e.Graphics;

bool selected = (e.State & DrawItemState.Selected) != 0;

Brush b = selected ?

SystemBrushes.HighlightText : Brushes.Blue;

e.DrawBackground();

g.FillEllipse(b, e.Bounds);

}Example 4-4. Simple owner-drawn menu item in VB

Private Sub menuItem_MeasureItem(sender As Object, _

e As System.Windows.Forms.MeasureItemEventArgs) _

Handles menuItem.MeasureItem

e.ItemHeight = 17

e.ItemWidth = 100

End Sub

Private Sub menuItem_DrawItem(sender As Object, _

e As System.Windows.Forms.DrawItemEventArgs) _

Handles menuItem.DrawItem

Dim g As Graphics = e.Graphics

Dim selected As Boolean = (e.State & DrawItemState.Selected) <> 0

Dim b As Brush

If selected Then

b = SystemBrushes.HighlightText

Else

b = Brushes.Blue

End If

e.DrawBackground()

g.FillEllipse(b, e.Bounds)

End SubNow that we have seen how to create menus, let us see how we can provide expert users with more direct access to the most frequently used operations with toolbars.

[15] The

other top level menus referenced here (menuEdit,

menuView, and menuHelp) would

be built in the same way as the File menu. The relevant code has been

omitted for conciseness.

[16] It is not the same event, despite looking identical. This is

because the Menu class is something of an

anomaly—despite being a visual class, it does not in fact

inherit from Control. It derives directly from

System.ComponentModel.Component (as does

Control). This seems to be because menus

don’t behave quite like other controls.

[17] The code is shown in C#. Once again, the VB

code is similar, except that the C# this keyword

is replaced with Me, and VB does not use the

semicolon to terminate a code statement.

Get .NET Windows Forms in a Nutshell now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.