Chapter 4. IP Network Scanning

This chapter focuses on the technical execution of IP network scanning. After undertaking initial reconnaissance to identify IP address spaces of interest, network scanning builds a clearer picture of accessible hosts and their network services. Network scanning and reconnaissance is the real data gathering exercise of an Internet-based security assessment. The rationale behind IP network scanning is to gain insight into the following elements of a given network:

ICMP message types that generate responses from target hosts

Accessible TCP and UDP network services running on the target hosts

Operating platforms of target hosts and their configuration

Areas of vulnerability within target host IP stack implementations (including sequence number predictability for TCP spoofing and session hijacking)

Configuration of filtering and security systems (including firewalls, border routers, switches, and IDS sensors)

Performing both network scanning and reconnaissance tasks paints a clear picture of the network topology and its security mechanisms. Before penetrating the target network, further assessment steps involve gathering specific information about the TCP and UDP network services that are running, including their versions and enabled options.

ICMP Probing

The Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) identifies potentially weak and poorly protected networks. ICMP is a short messaging protocol that’s used by systems administrators and end users for continuity testing of networks (e.g., using the ping or traceroute commands). From a network scanning and probing perspective, the following types of ICMP messages are useful:

- Type 8 (echo request)

Echo request messages are also known as ping packets. You can use a scanning tool such as nmap to perform ping sweeping and easily identify hosts that are accessible.

- Type 13 (timestamp request)

A timestamp request message requests system time information from the target host. The response is in a decimal format and is the number of milliseconds elapsed since midnight GMT.

- Type 15 (information request)

The ICMP information request message was intended to support self-configuring systems such as diskless workstations at boot time, to allow them to discover their network address. Protocols such as RARP, BOOTP, or DHCP do so more robustly, so type 15 messages are rarely used.

- Type 17 (subnet address mask request)

An address mask request message reveals the subnet mask used by the target host. This information is useful when mapping networks and identifying the size of subnets and network spaces used by organizations.

Firewalls of security-conscious organizations often blanket-filter inbound ICMP messages and so ICMP probing isn’t effective; however, ICMP isn’t filtered in most networks because ICMP messages are often useful for network troubleshooting purposes.

There are a handful of other ICMP message types that have relevant security applications (such as ICMP type 5 redirect messages sent by routers), but they aren’t related to network scanning.

Table 4-1 outlines popular operating systems and their responses to certain types of direct ICMP query messages.

Operating system | Direct ICMP message types (non-broadcast) | |||

8 | 13 | 15 | 17 | |

Linux | Yes | Yes | No | No |

*BSD | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Solaris | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

HP-UX | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

AIX | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Ultrix | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Windows 95, 98, and ME | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

Windows NT 4.0 | Yes | No | No | No |

Windows 2000 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Cisco IOS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Indirect ICMP query messages can be sent to the broadcast address of a given subnet (such as 192.168.0.255 in a 192.168.0.0/24 network). Operating systems

respond in different ways to indirect queries issued to a broadcast

address, as shown in Table

4-2.

Operating system | Indirect ICMP message types (broadcast) | |||

8 | 13 | 15 | 17 | |

Linux | Yes | Yes | No | No |

*BSD | No | No | No | No |

Solaris | Yes | Yes | No | No |

HP-UX | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

AIX | No | No | No | No |

Ultrix | No | No | No | No |

Windows 95, 98, and ME | No | No | No | No |

Windows NT 4.0 | No | No | No | No |

Windows 2000 | No | No | No | No |

Cisco IOS | No | No | Yes | No |

Ofir Arkin of the Sys-Security Group (http://www.sys-security.com) has undertaken a lot of research into ICMP over recent years, publishing white papers dedicated entirely to the use of ICMP probes for OS fingerprinting. For quality in-depth details of ICMP probing techniques, please consult his research available from his web site.

SING

Send ICMP Nasty Garbage (SING) is a command-line tool that sends fully customizable ICMP packets. The main purpose of the tool is to replace the ping command with certain enhancements, including the ability to transmit and receive spoofed packets, send MAC-spoofed packets, and support the transmission of many other message types, including ICMP address mask, timestamp, and information requests, router solicitation, and router advertisement messages.

SING is available from http://sourceforge.net/projects/sing/.[1] Examples using the sing utility to launch ICMP echo, timestamp, and address mask requests follow. In these examples, I direct probes at broadcast addresses and individual hosts.

Using sing to send broadcast ICMP echo request messages:

# sing -echo 192.168.0.255

SINGing to 192.168.0.255 (192.168.0.255): 16 data bytes

16 bytes from 192.168.0.1: seq=0 ttl=64 TOS=0 time=0.230 ms

16 bytes from 192.168.0.155: seq=0 ttl=64 TOS=0 time=2.267 ms

16 bytes from 192.168.0.126: seq=0 ttl=64 TOS=0 time=2.491 ms

16 bytes from 192.168.0.50: seq=0 ttl=64 TOS=0 time=2.202 ms

16 bytes from 192.168.0.89: seq=0 ttl=64 TOS=0 time=1.572 msUsing sing to send ICMP timestamp request messages:

# sing -tstamp 192.168.0.50

SINGing to 192.168.0.50 (192.168.0.50): 20 data bytes

20 bytes from 192.168.0.50: seq=0 ttl=128 TOS=0 diff=327372878

20 bytes from 192.168.0.50: seq=1 ttl=128 TOS=0 diff=1938181226*

20 bytes from 192.168.0.50: seq=2 ttl=128 TOS=0 diff=1552566402*

20 bytes from 192.168.0.50: seq=3 ttl=128 TOS=0 diff=1183728794*Using sing to send ICMP address mask request messages:

# sing -mask 192.168.0.25

SINGing to 192.168.0.25 (192.168.0.25): 12 data bytes

12 bytes from 192.168.0.25: seq=0 ttl=236 mask=255.255.255.0

12 bytes from 192.168.0.25: seq=1 ttl=236 mask=255.255.255.0

12 bytes from 192.168.0.25: seq=2 ttl=236 mask=255.255.255.0

12 bytes from 192.168.0.25: seq=3 ttl=236 mask=255.255.255.0nmap

nmap can perform ICMP ping-sweep scans of target address spaces easily and relatively

quickly. Many hardened networks will blanket-filter inbound ICMP

messages at border routers or firewalls, so sweeping in this fashion

isn’t effective in some cases. Example 4-1 demonstrates how

nmap can be run from a Unix-based

or Win32 command prompt to perform an ICMP ping sweep against 192.168.0.0/24. nmap is available from http://www.insecure.org/nmap/.

# nmap -sP -PI 192.168.0.0/24

Starting nmap 3.45 ( www.insecure.org/nmap/ )

Host (192.168.0.0) seems to be a subnet broadcast address (2 extra pings).

Host (192.168.0.1) appears to be up.

Host (192.168.0.25) appears to be up.

Host (192.168.0.32) appears to be up.

Host (192.168.0.50) appears to be up.

Host (192.168.0.65) appears to be up.

Host (192.168.0.102) appears to be up.

Host (192.168.0.110) appears to be up.

Host (192.168.0.155) appears to be up.

Host (192.168.0.255) seems to be a subnet broadcast address (2 extra pings).

Nmap run completed -- 256 IP addresses (8 hosts up)Tip

Using the -sP ping sweep

flag within nmap doesn’t just

perform an ICMP echo request to each IP address; it also sends TCP

ACK and SYN probe packets to port 80 of each host. In Example 4-1, nmap is run with the -PI flag, to specify that we’re sending

only ICMP echo requests. Overall, using the standard -sP flag is often more effective because it

identifies web servers that may not respond to ICMP probes; however,

in some environments it is beneficial to use more specific probe

types.

Gleaning Internal IP Addresses

In some cases, it is possible to gather internal IP address information by analyzing all ICMP responses with a stateful inspection system such as a personal firewall on your workstation or a Linux machine on the edge of your network performing stateful inspection of all IP traffic.

After sending an ICMP echo request to a publicly accessible IP address, the target firewall often uses network address translation to forward the packet to the correct internal IP address (within a DMZ or internal network space). If the firewall is configured to permit ICMP echo request messages to go through and fully forwards ICMP echo request messages (as opposed to rewriting the headers as proxies do), sometimes unsolicited ICMP echo reply messages appear from private IP addresses.

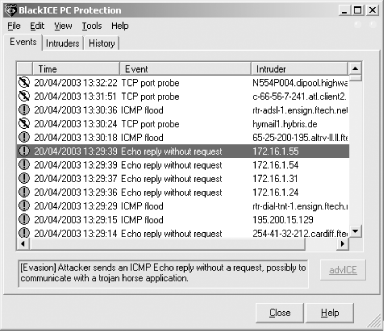

Tools such as nmap and sing don’t identify these responses from private addresses, because doing so requires low-level stateful analysis of the traffic flowing into and out of a network, such as performed by a firewall. A quick and simple example of this behavior is to watch the ISS BlackICE event log in Figure 4-1 as a simple ICMP ping sweep is undertaken using SuperScan or a similar tool.

Figure 4-1 shows

that ISS BlackICE has identified four unsolicited ICMP echo replies

from private addresses (within the 172.16.0.0/16 space in this case, but they

are often within 192.168.0.0/16 or

10.0.0.0/8). By carefully

monitoring such a stateful inspection mechanism when performing any

kind of probing or network scanning, you can gain useful insight into

areas of target network configuration.

A Linux system running tcpdump or ethereal can be used to great effect on our penetration testing launch network simply by picking up ICMP echo reply messages and filtering out public and nonpublic addresses using simple awk scripts.

Identifying Subnet Broadcast Addresses

Subnet broadcast addresses can be easily extracted using functionality within nmap that monitors the number of ICMP echo replies when a ping sweep is initiated. Such broadcast addresses will respond with multiple replies if they aren’t filtered, which lets you see how to segment the target network space. Example 4-2 shows nmap mapping out the broadcast addresses in use for a pool of ADSL routers and systems.

# nmap -sP 62.2.15.0/24

Starting nmap 3.45 ( www.insecure.org/nmap/ )

Host 62.2.15.8 seems to be a subnet broadcast address (returned 1 extra pings).

Host pipex-gw.abcconsulting.co.uk (62.2.15.9) appears to be up.

Host mail.abc.co.uk (62.2.15.10) appears to be up.

Host www-dev.abc.co.uk (62.2.15.13) appears to be up.

Host 62.2.15.15 seems to be a subnet broadcast address (returned 1 extra pings).

Host 62.2.15.16 seems to be a subnet broadcast address (returned 1 extra pings).

Host pipex-gw.smallco.net (62.2.15.17) appears to be up.

Host mail.smallco.net (62.2.15.18) appears to be up.

Host 62.2.15.19 seems to be a subnet broadcast address (returned 1 extra pings).

Host 62.2.15.20 seems to be a subnet broadcast address (returned 1 extra pings).

Host pipex-gw.example.org (62.2.15.21) appears to be up.

Host mail.example.org (62.2.15.22) appears to be up.

Host www.example.org (62.2.15.25) appears to be up.

Host ext-26.example.org (62.2.15.26) appears to be up.

Host ext-27.example.org (62.2.15.27) appears to be up.

Host staging.example.org (62.2.15.28) appears to be up.

Host 62.2.15.35 seems to be a subnet broadcast address (returned 1 extra pings).This scan has identified three separate subnets within the

62.2.15.0 network:

TCP Port Scanning

Accessible TCP ports can be identified by port scanning target IP addresses. The following nine different types of TCP port scanning are used in the wild by both attackers and security consultants:

- Standard scanning methods

Vanilla connect( )scanningHalf-open SYN flag scanning - Stealth TCP scanning methods

Inverse TCP flag scanning ACK flag probe scanning TCP fragmentation scanning - Third-party and spoofed TCP scanning methods

FTP bounce scanning Proxy bounce scanning Sniffer-based spoofed scanning IP ID header scanning

What follows is a technical breakdown for each TCP port scanning type, along with details of Windows and Unix-based tools that can perform scanning.

Standard Scanning Methods

Standard scanning methods, such as vanilla and half-open SYN scanning, are extremely simple direct techniques used to identify accessible TCP ports and services accurately. These scanning methods are reliable but are easily logged and identified.

Vanilla connect( ) scanning

TCP connect( ) port scanning is the most simple type of probe to

launch. There is no stealth whatsoever involved in this form of

scanning because a full TCP/IP connection is established with TCP

port one of the target host, then incrementally through ports two,

three, four, and so on.

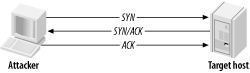

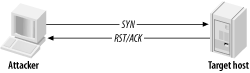

TCP/IP’s reliability as a protocol, vanilla port scanning is a very accurate way to determine which TCP services are accessible on a given target host. Figures Figure 4-2 and Figure 4-3 show the various TCP packets and their flags, as they are sent and received by the attacker and the host he is scanning.

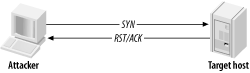

In Figure 4-2, the attacker first sends a SYN probe packet to the port he wishes to test. Upon receiving a packet from the port with the SYN and ACK flags set, he knows that the port is open. The attacker completes the three-way handshake by sending an ACK packet back.

If, however, the target port is closed, the attacker receives an RST/ACK packet directly back, as shown in Figure 4-3.

As before, the attacker sends a SYN probe packet, but the

target server responds with an RST/ACK. Standard connect( ) scanning in this way is a

reliable way to identify accessible TCP network services. The

downside is that the scanning type is extremely simple and hence

easily identified and logged.

Tools that perform connect( ) TCP scanning

nmap can perform a TCP

connect( ) port scan using the

-sT flag. Other very simple

scanners exist; one such as pscan.c, which is available as source

code from many sites, including Packet Storm (http://www.packetstormsecurity.org).

For Windows, Foundstone’s SuperScan is an excellent port-scanning utility with good functionality. It’s available from http://www.foundstone.com/knowledge/scanning.html.

Tip

When performing a full assessment exercise, every TCP port from 0 to 65535 should be checked. For speed reasons, tools such as SuperScan and nmap have internal lists of only some 1,500 common ports to check; thus they often miss all kinds of interesting services that can be found on high ports—for example, Check Point SVN web services on TCP port 18264.

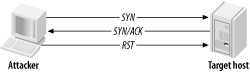

Half-open SYN flag scanning

Usually, a three-way handshake is initiated to synchronize a connection between two hosts; the client sends a SYN packet to the server, which responds with SYN and ACK if the port is open, and the client then sends an ACK to complete the handshake.

In the case of half-open SYN port scanning when a port is found to be listening, an RST packet is sent as the third part of the handshake. Sending an RST packet in this way abruptly resets the TCP connection, and because you have not completed the three-way handshake, the connection attempt often isn’t logged on the target host.

Most intrusion detection systems (IDS) and other security programs, such as portsentry , can easily detect and prevent half-open SYN port-scanning attempts. In cases where stealth is required, other techniques are recommended, such as FIN or TTL-based scanning, or even using a utility such as fragroute , to fragment outbound probe packets.

Figures Figure 4-4 and Figure 4-5 outline the packets sent between the two hosts when launching a SYN port scan and finding either an open and a closed port.

In Figure 4-5, a

SYN probe packet is sent to the target port; a SYN/ACK

packet is received indicating that the port is open. Normally at

this stage, a connect( ) scanner

sends an ACK packet to establish the connection, but this is

half-open scanning so instead, a RST packet is sent to tear down the

connection.

Figure 4-4 shows that when a closed port is found, a RST/ACK packet is received, and nothing happens (as before in Figure 4-3). The benefit of half-open scanning is that a true three-way TCP handshake is never completed, and the connection doesn’t appear to be established.

Nowadays, all IDS and personal firewall systems can identify SYN port scans (although they often mislabel them as SYN flood attacks due to the number of probe packets). SYN scanning is fast and reliable, although it requires raw access to network sockets and, therefore, privileged access to Unix and Windows hosts.

Tools that perform half-open SYN scanning

nmap can perform a SYN

port scan under both Unix and Windows environments

using the -sS flag. Many other

Unix half-open port scanners exist, including strobe, which is available in source

form from many sites including Packet Storm (http://www.packetstormsecurity.org).

Tip

The -T flag can be used

within nmap to change the

timing policy used when scanning. Networks protected by

commercial firewalls (NetScreen, WatchGuard, and Check Point in

particular) will sometimes drop SYN probes if nmap is sending the packets out too

quickly, nmap’s actions

resemble a SYN flood denial of service attack. I have found that

by setting the timing policy to -T Sneaky, it’s often possible to glean

accurate results against hosts protected by firewalls with SYN

flood protection enabled.

A second SYN port scanner worth mentioning is the scanrand component of the Paketto Keiretsu suite by Dan Kaminsky. Paketto Keiretsu contains a number of useful networking utilities that are available at http://www.doxpara.com/read.php/code/paketto.html. The scanrand tool is very well designed, with distinct SYN probing and background listening components so that you can launch the quickest possible scans. Inverse SYN cookies (using the HMAC SHA1 hashing algorithm) tag outgoing probe packets, so that false positive results become nonexistent (because the listening component registers only SYN/ACK responses with the correct cryptographic cookies). Example 4-3 shows scanrand identifying open ports on a local network in less than one second.

# scanrand 10.0.1.1-254:quick

UP: 10.0.1.38:80 [01] 0.003s

UP: 10.0.1.110:443 [01] 0.017s

UP: 10.0.1.254:443 [01] 0.021s

UP: 10.0.1.57:445 [01] 0.024s

UP: 10.0.1.59:445 [01] 0.024s

UP: 10.0.1.38:22 [01] 0.047s

UP: 10.0.1.110:22 [01] 0.058s

UP: 10.0.1.110:23 [01] 0.058s

UP: 10.0.1.254:22 [01] 0.077s

UP: 10.0.1.254:23 [01] 0.077s

UP: 10.0.1.25:135 [01] 0.088s

UP: 10.0.1.57:135 [01] 0.089s

UP: 10.0.1.59:135 [01] 0.090s

UP: 10.0.1.25:139 [01] 0.097s

UP: 10.0.1.27:139 [01] 0.098s

UP: 10.0.1.57:139 [01] 0.099s

UP: 10.0.1.59:139 [01] 0.099s

UP: 10.0.1.38:111 [01] 0.127s

UP: 10.0.1.57:1025 [01] 0.147s

UP: 10.0.1.59:1025 [01] 0.147s

UP: 10.0.1.57:5000 [01] 0.156s

UP: 10.0.1.59:5000 [01] 0.157s

UP: 10.0.1.53:111 [01] 0.182sDue to the way scanrand sends a deluge of SYN probes and then listens for positive SYN/ACK responses, the order in which the open ports are displayed will look a little odd. On the positive side, scanrand is lightning fast; it allows specific ports (e.g., common backdoors) to be identified in seconds even across large networks, as opposed to minutes or hours with a bulkier tool such as nmap.

Stealth TCP Scanning Methods

Stealth scanning methods involve idiosyncrasies in the way TCP/IP stacks of target hosts process and respond to packets with strange bits set or other features. Such techniques aren’t effective at accurately mapping the open ports of some operating systems but do provide a degree of stealth and are sometimes not logged.

Inverse TCP flag scanning

Security mechanisms such as firewalls and IDS usually detect SYN packets being sent to sensitive ports of target hosts. Programs are also available to log half-open SYN flag scan attempts, including synlogger and courtney . Probe packets with strange TCP flags set can sometimes pass through filters undetected, depending on the security mechanisms deployed.

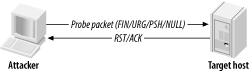

Using malformed TCP flags to probe a target is known as an inverted technique because responses are sent back only by closed ports. RFC 793 states that if a port is closed on a host, an RST/ACK packet should be sent to reset the connection. To take advantage of this feature, attackers send TCP probe packets with various TCP flags set.

A TCP probe packet is sent to each port of the target host. Three types of probe packet flag configurations are normally used:

A FIN probe with the FIN TCP flag set

An XMAS probe with the FIN, URG, and PUSH TCP flags set

A NULL probe with no TCP flags set

Figures Figure 4-6 and Figure 4-7 depict the probe packets and responses generated by the target host if the target port is found to be open or closed.

The RFC standard states that, if no response is seen from the target port, the port is open, or the server is down. This scanning method isn’t necessarily the most accurate, but it is stealthy; it sends garbage to each port that usually won’t be picked up.

For all closed ports on the target host, RST/ACK packets are received. However, some operating platforms (such as those in the Microsoft Windows family) disregard the RFC 793 standard, so no RST/ACK response is seen when an attempt is made to connect to a closed port. Hence, this technique is effective against most Unix-based operating systems.

Tools that perform inverse TCP flag scanning

nmap can perform an inverse TCP flag port scan under both Unix and Windows environments, using the following flags:

-sFFor a scan with only the FIN flag set on probe packets

-sNFor a NULL scan with no TCP flags set on probe packets

-sXFor an Xmas tree scan with all TCP flags set

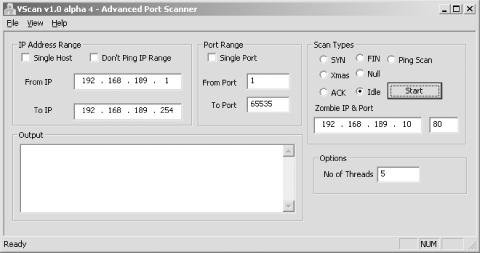

vscan is another Windows tool you can use to perform inverse TCP flag scanning. The utility doesn’t require installation of WinPcap network drivers; instead it uses raw sockets within Winsock 2 (present in Windows 2000, XP, and 2003). vscan is available at http://host.deluxnetwork.com/~vsniff/vscan.zip.

ACK flag probe scanning

A stealthy technique documented by Uriel Maimon in Phrack Magazine, Issue 49, is that of identifying open TCP ports by sending ACK probe packets and analyzing the header information of the RST packets received from the target host. This technique exploits vulnerabilities within the BSD derived TCP/IP stack and is therefore only effective against certain operating systems and platforms. There are two main ACK scanning techniques that involve:

Analysis of the time-to-live (TTL) field of received packets

Analysis of the WINDOW field of received packets

These techniques can also check filtering systems and complicated networks to understand the processes packets go through on the target network. For example, the TTL value can be used as a marker of how many systems the packet has hopped through. The firewalk filter assessment tool works in a similar fashion, available from http://www.packetfactory.net/projects/firewalk/.

Analysis of the TTL field of received packets

To analyze the TTL field data of received RST packets, an attacker first sends thousands of crafted ACK packets to different TCP ports, as shown in Figure 4-8.

Here is a log of the first four RST packets received using the hping2 utility:

1: host 192.168.0.12 port 20: F:RST -> ttl: 70 win: 0 2: host 192.168.0.12 port 21: F:RST -> ttl: 70 win: 0 3: host 192.168.0.12 port 22: F:RST -> ttl: 40 win: 0 4: host 192.168.0.12 port 23: F:RST -> ttl: 70 win: 0

By analyzing the TTL value of each packet, an attacker can easily see that the value returned by port 22 is 40, whereas the other ports return a value of 70. This suggests that port 22 is open on the target host because the TTL value returned is smaller than the TTL boundary value of 64.

Analysis of the WINDOW field of received packets

To analyze the WINDOW field data of received RST packets, an attacker sends thousands of the same crafted ACK packets to different TCP ports (as shown in Figure 4-8). Here is a log of the first four RST packets received, again using the hping2 utility:

1: host 192.168.0.20 port 20: F:RST -> ttl: 64 win: 0 2: host 192.168.0.20 port 21: F:RST -> ttl: 64 win: 0 3: host 192.168.0.20 port 22: F:RST -> ttl: 64 win: 512 4: host 192.168.0.20 port 23: F:RST -> ttl: 64 win: 0

Notice that the TTL value for each packet is 64, meaning that TTL analysis of the packets isn’t effective in identifying open ports on this host. However, by analyzing the WINDOW values, the attacker finds that the third packet has a non-zero value, indicating an open port.

The advantage of using ACK flag probe scanning is that detection is difficult (for both IDS and host-based systems, such as personal firewalls). The disadvantage is that this scanning type relies on TCP/IP stack implementation bugs, which are prominent in BSD-derived systems but not in many other modern platforms.

Tools that perform ACK flag probe scanning

nmap supports

ACK flag probe scanning, with the -sA and -sW flags to analyze the TTL and WINDOW

values respectively. See the nmap manpage for more detailed

information.

hping2 can also sample TTL and WINDOW values, but this can prove highly time consuming in most cases. The tool is more useful for analyzing low-level responses, as opposed to port scanning in this fashion. hping2 is available from http://www.hping.org.

Third-Party and Spoofed TCP Scanning Methods

Third-party port scanning methods allow for probes to be effectively bounced through vulnerable servers to hide the true source of the network scanning. An additional benefit of using a third-party technique in this way is that insight into firewall configuration can be gained by potentially bouncing scans through trusted hosts that are vulnerable.

FTP bounce scanning

Hosts running outdated FTP services can relay numerous TCP attacks, including

port scanning. There is a flaw in the way many FTP servers handle

connections using the PORT

command (see RFC 959 or technical description of the PORT feature) that allows for data to be

sent to user-specified hosts and ports. In their default

configurations, the FTP services running on the following platforms

are affected:

FreeBSD 2.1.7 and earlier

HP-UX 10.10 and earlier

Solaris 2.6/SunOS 5.6 and earlier

SunOS 4.1.4 and earlier

SCO OpenServer 5.0.4 and earlier

SCO UnixWare 2.1 and earlier

IBM AIX 4.3 and earlier

Caldera Linux 1.2 and earlier

Red Hat Linux 4.2 and earlier

Slackware 3.3 and earlier

Any Linux distribution running WU-FTP 2.4.2-BETA-16 or earlier

The FTP bounce attack can have a far more devastating effect

if a writable directory exists because a series of commands or other

data can be entered into a file and then relayed via the PORT command to a specified port of a

target host. For example, someone can upload a spam email message to

a vulnerable FTP server and then send this email message to the SMTP

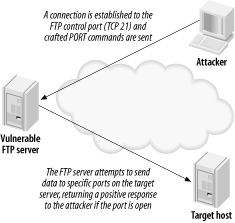

port of a target mail server. Figure 4-9 shows the parties

involved in FTP bounce scanning.

The following occurs when performing an FTP bounce scan:

The attacker connects to the FTP control port (TCP port 21) of the vulnerable FTP server that she is going to bounce her attack through and enters passive mode, forcing the FTP server to send data using DTP (data transfer process) to a specific port of a specific host:

QUOTE PASV227 Entering Passive Mode (64,12,168,246,56,185).A

PORTcommand is issued, with an argument passed to the FTP service telling it to attempt a connection to a specific TCP port of the target server; for example, TCP port 23 of144.51.17.230:PORT 144,51,17,230,0,23200 PORT command successful.After issuing the

PORTcommand, aLISTcommand is sent. The FTP server then attempts to create a connection with the target host defined in thePORTcommand issued previously:LIST150 Opening ASCII mode data connection for file list 226 Transfer complete.If a 226 response is seen, then the port on the target host is open. If, however, a 425 response is seen, the connection has been refused:

LIST425 Can't build data connection: Connection refused

Proxy bounce scanning

Attackers bounce TCP attacks through open proxy servers. Depending on the level of poor configuration, the server will sometimes allow a full-blown TCP port scan to be relayed. Using proxy servers to perform bounce port scanning in this fashion is often time consuming, so many attackers prefer to abuse open proxy servers more efficiently by bouncing actual attacks through to target networks.

ppscan.c, a publicly available Unix-based tool to bounce port scans, can be found in source form at:

| http://www.dsinet.org/tools/network-scanners/ppscan.c |

| http://www.phreak.org/archives/exploits/unix/network-scanners/ppscan.c |

Sniffer-based spoofed scanning

An innovative half-open SYN TCP port scanning method was realized when jsbach published his spoofscan Unix-based scanner in 1998. The spoofscan tool is run as root on a given host to perform a stealthy port scan. The key feature that makes this scanner so innovative is that it places the host network card into promiscuous mode and then sniffs for responses on the local network segment.

The following unique benefits are immediately realized when using a sniffer-based spoofing port scanner:

If you have superuser access to a machine on the same physical network segment as the target host or a firewall protecting a target host, you can spoof TCP probes from other IP addresses to identify trusted hosts and to gain insight into the firewall policy (by spoofing scans from trusted office hosts, for example). Accurate results will be retrieved because of the background sniffing process, which monitors the local network segment for responses to your spoofed probes.

If you have access to a large shared network segment, you can spoof scans from hosts you don’t have access to or that don’t exist (such as unused IP addresses within your local network segment), to effectively port scan remote networks in a distributed and stealthy fashion.

The beauty of this method is that the attacker is abusing his access to the local network segment. Such techniques can even be carried out to good effect in switched network environments using ARP redirect spoofing and other techniques. spoofscan is available at http://examples.oreilly.com/networksa/tools/spoofscan.c.

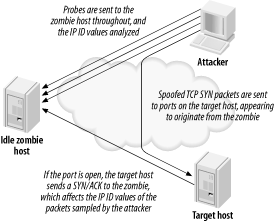

IP ID header scanning

IP ID header scanning (also known as idle or dumb scanning) is an obscure scanning technique that involves abusing implementation peculiarities within the TCP/IP stack of most operating systems. Three hosts are involved:

The host, from which the scan is launched

The target host, which will be scanned

A zombie or idle host, which is an Internet-based server that is queried with spoofed port scanning against the target host to identify open ports from the perspective of the zombie host

IP ID header scanning is extraordinarily stealthy due to its blind nature. Determined attackers will often use this type of scan to map out IP-based trust relationships between machines, such as firewalls and VPN gateways.

The listing returned by the scan shows open ports from the perspective of the zombie host, so you can try scanning a target using various zombies you think might be trusted (such as hosts at remote offices or DMZ machines). Figure 4-10 depicts the process undertaken during an IP ID header scan.

hping2 was originally used in a manual fashion to perform such low-level TCP scanning, which was time consuming and tricky to undertake against an entire network of hosts. A white paper that fully discusses using the tool to perform IP ID header scanning by hand is available from http://www.kyuzz.org/antirez/papers/dumbscan.html.

nmap supports such IP ID header scanning with the option:

-sI <zombie host[:probe port]>

Example 4-4 shows

how nmap uses this

functionality to scan 192.168.0.50 through 192.168.0.155.

# nmap -P0 -sI 192.168.0.155 192.168.0.50

Starting nmap 3.45 ( www.insecure.org/nmap/ )

Idlescan using zombie 192.168.0.155; Class: Incremental

Interesting ports on (192.168.0.50):

(The 1582 ports scanned but not shown below are in state: closed)

Port State Service

25/tcp open smtp

53/tcp open domain

80/tcp open http

88/tcp open kerberos-sec

135/tcp open loc-srv

139/tcp open netbios-ssn

389/tcp open ldap

443/tcp open https

445/tcp open microsoft-ds

464/tcp open kpasswd5

593/tcp open http-rpc-epmap

636/tcp open ldapssl

1026/tcp open LSA-or-nterm

1029/tcp open ms-lsa

1033/tcp open netinfo

3268/tcp open globalcatLDAP

3269/tcp open globalcatLDAPssl

3372/tcp open msdtc

3389/tcp open ms-term-serv

Nmap run completed -- 1 IP address (1 host up)Warning

If nmap is run without

the -P0 flag when performing

third-party scanning, the source IP address of the attacker’s host

performs ICMP and TCP pinging of the target hosts before starting

to scan; this can appear in firewall and IDS audit logs of

security-conscious organizations.

vscan is another Windows tool that can perform the same inverse IP ID scanning. As discussed earlier, the vscan utility doesn’t require installation of WinPcap network drivers. Instead, it uses raw sockets within Winsock 2 (present in Windows 2000, XP, and 2003). vscan is available at http://host.deluxnetwork.com/~vsniff/vscan.zip.

Figure 4-11 shows the vscan utility in use, along with its options and functionality.

UDP Port Scanning

Because UDP is a connectionless protocol, there are only two ways to effectively enumerate accessible UDP network services across an IP network:

Send UDP probe packets to all 65535 UDP ports, then wait for “ICMP destination port unreachable” messages to identify UDP ports that aren’t accessible.

Use specific UDP service clients (such as snmpwalk, dig, or tftp) to send UDP datagrams to target UDP network services and await a positive response.

Many security-conscious organizations filter ICMP messages to and from their Internet-based hosts, so it is often difficult to assess which UDP services are accessible via simple port scanning. If “ICMP destination port unreachable” messages can escape the target network, a traditional UDP port scan can be undertaken to deductively identify open UDP ports on target hosts.

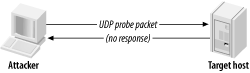

Figures Figure 4-12 and Figure 4-13 show the UDP packets and ICMP responses generated by hosts when ports are open and closed.

UDP port scanning is an inverted scanning type in which open ports don’t respond. What is looked for, in particular, are ICMP destination port unreachable (type 3 code 3) messages from the target host, as shown in Figure 4-13.

Tools That Perform UDP Port Scanning

nmap supports UDP port

scanning with the - sU option. The latest version of Foundstone’s SuperScan also supports UDP port scanning. However, both tools wait for negative

“ICMP destination port unreachable” messages to identify open ports

(i.e., those ports that don’t respond). If these ICMP messages are

filtered by a firewall as they try to travel out of the target

network, inaccurate results are gleaned.

During a comprehensive audit of Internet-based network space, you should send crafted UDP client packets to popular services and await a positive response. The scanudp utility developed by Fryxar (http://www.geocities.com/fryxar/) does this very well.

Example 4-5 shows

the scanudp utility being

downloaded, compiled, and run from my Linux launch system against a

Windows 2000 server at 192.168.0.50.

#wget http://www.geocities.com/fryxar/scanudp_v2.tgz#tar xvfz scanudp_v2.tgzscanudp/ scanudp/scanudp.c scanudp/enum.c scanudp/enum.h scanudp/makefile scanudp/enum.o scanudp/scanudp.o scanudp/scanudp #cd scanudp#makegcc enum.o scanudp.o -o scanudp #./scanudp./scanudp v2.0 - by: Fryxar usage: ./scanudp [options] <host> options: -t <timeout> Set port scanning timeout -b <bps> Set max bandwidth -v Verbose Supported protocol: echo daytime chargen dns tftp ntp ns-netbios snmp(ILMI) snmp(public) #./scanudp 192.168.0.50192.168.0.50 53 192.168.0.50 137 192.168.0.50 161

IDS Evasion and Filter Circumvention

IDS evasion, when launching any type of IP probe or scan, involves one or both of the following tactics:

Use of fragmented probe packets, assembled when they reach the target host

Use of spoofing to emulate multiple fake hosts launching network scanning probes, in which the real IP address of the scanning host is inserted to collect results

Filtering mechanisms can be circumvented at times using malformed or fragmented packets. However, the common techniques used to bypass packet filters at either the network or system-kernel level are as follows:

Use of source routing

Use of specific TCP or UDP source ports

First, I’ll discuss IDS evasion techniques of fragmenting data and emulating multiple hosts, and then filter circumvention methodologies. These techniques can often be mixed to launch attacks using source routed, fragmented packets to bypass both filters and IDS systems.

Fragmenting Probe Packets

Probe packets can be fragmented easily with fragroute to fragment all probe packets flowing from your host or network or with a port scanner that supports simple fragmentation, such as nmap. Many IDS sensors can’t process large volumes of fragmented packets because doing so creates a large overhead in terms of memory and CPU consumption at the network sensor level.

fragtest

Dug Song’s fragtest utility (available as part of the fragroute package from http://www.monkey.org/~dugsong/fragroute/) can determine exactly which types of fragmented ICMP messages are processed and responded to by the remote host. ICMP echo request messages are used by fragtest for simplicity and allow for easy analysis; the downside is that the tool can’t assess hosts that don’t respond to ICMP messages.

After undertaking ICMP probing exercises (such as ping sweeping and hands-on use of the sing utility) to ensure that ICMP messages are processed and responded to by the remote host, fragtest can perform three particularly useful tests:

Send an ICMP echo request message in 8-byte fragments (using the

fragoption)Send an ICMP echo request message in 8-byte fragments, along with a 16-byte overlapping fragment, favoring newer data in reassembly (using the

frag-newoption)Send an ICMP echo request message in 8-byte fragments, along with a 16-byte overlapping fragment, favoring older data in reassembly (using the

frag-oldoption)

Here is an example that uses fragtest to assess responses to

fragmented ICMP echo request messages with the frag, frag-new, and frag-old options:

# fragtest frag frag-new frag-old www.bbc.co.uk

frag: 467.695 ms

frag-new: 516.327 ms

frag-old: 471.260 msAfter ascertaining that fragmented and overlapped packets are indeed processed correctly by the target host and not dropped by firewalls or security mechanisms, a tool such as fragroute can be used to fragment all IP traffic destined for the target host.

fragroute

Dug Song’s fragroute utility intercepts, modifies, and rewrites egress traffic destined for a specific host, according to a predefined rule set. When built and installed, Version 1.2 comprises the following binary and configuration files:

| /usr/local/sbin/fragtest |

| /usr/local/sbin/fragroute |

| /usr/local/etc/fragroute.conf |

The fragroute.conf file defines the way fragroute fragments, delays, drops, duplicates, segments, interleaves, and generally mangles outbound IP traffic.

Using the default configuration file, fragroute can be run from the command line in the following manner:

#cat /usr/local/etc/fragroute.conftcp_seg 1 new ip_frag 24 ip_chaff dup order random print #fragrouteUsage: fragroute [-f file] dst #fragroute 192.168.102.251fragroute: tcp_seg -> ip_frag -> ip_chaff -> order -> print

Egress traffic processed by fragroute is displayed in tcpdump format if the print option is used in the configuration

file. When running fragroute in

its default configuration, TCP data is broken down into 1-byte

segments and IP data into 24-byte segments, along with IP chaffing

and random reordering of the outbound packets.

fragroute.conf

The fragroute manpage

covers all the variables that can be set within the configuration

file. The type of IP fragmentation and reordering used by

fragtest when using the

frag-new option can be applied

to all outbound IP traffic destined for a specific host by

defining the following variables in the fragroute.conf file:

ip_frag 8 old order random print

TCP data can be segmented into 4-byte, forward-overlapping chunks (favoring newer data), interleaved with random chaff segments bearing older timestamp options (for PAWS elimination), and reordered randomly using these fragroute.conf variables:

tcp_seg 4 new tcp_chaff paws order random print

I recommend testing the variables used by fragroute in a controlled environment before live networks and systems are tested. This ensures that you see decent results when passing probes through fragroute and allows you to check for adverse reactions to fragmented traffic being processed. Applications and hardware appliances alike have been known to crash and hang from processing heavily fragmented and mangled data!

nmap

nmap can fragment probe packets when launching half-open SYN or inverse TCP scanning types. The TCP header itself is split over several packets to make it more difficult for packet filters and IDS systems to detect the port scan. While most firewalls in high security environments queue all the IP fragments before processing them, some networks disable this functionality because of the performance hit incurred. Example 4-6 uses nmap to perform a half-open SYN TCP scan using fragmented packets.

# nmap -sS -f 192.168.102.251

Starting nmap 3.45 ( www.insecure.org/nmap/ )

Interesting ports on cartman (192.168.102.251):

(The 1524 ports scanned but not shown below are in state: closed)

Port State Service

25/tcp open smtp

53/tcp open domain

8080/tcp open http-proxy

Nmap run completed -- 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 0 secondsEmulating Multiple Attacking Hosts

By emulating a large number of attacking hosts all launching probes and port scans against a target network, IDS alert and logging systems will be rendered effectively useless. nmap allows for decoy hosts to be defined, so that a target host can be scanned from a plethora of spoofed addresses (thus obscuring your own IP address).

The flag that defines decoy addresses within nmap is -D

[decoy1,ME,decoy2,decoy3,...]. Example 4-7 shows nmap being used in this fashion to scan

192.168.102.251.

# nmap -sS -P0 -D 62.232.12.8,ME,65.213.217.241 192.168.102.251

Starting nmap 3.45 ( www.insecure.org/nmap/ )

Interesting ports on cartman (192.168.102.251):

(The 1524 ports scanned but not shown below are in state: closed)

Port State Service

25/tcp open smtp

53/tcp open domain

8080/tcp open http-proxy

Nmap run completed -- 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 0 secondsNotice that the -P0 flag is

also specified. When performing any kind of stealth attack, it is

important that even initial probing (in the case of nmap, an ICMP echo request and attempted

connection to TCP port 80) isn’t undertaken, because it will reveal

the true source of the attack in many cases.

Source Routing

Source routing is a feature traditionally used for network troubleshooting purposes. Tools such as traceroute can be provided with details of gateways the packet should be loosely or strictly routed through so that specific routing paths can be tested. Source routing allows you to specify which gateways and routes your packets should take, instead of allowing routers and gateways to query their own routing tables to determine the next hop.

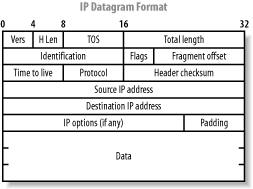

Source routing information is provided as an IP options field in the packet header, as shown in Figure 4-14.

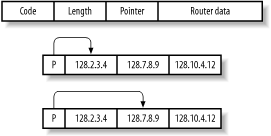

The format of the IP option data within a source-routed packet is quite simple. The first three bytes are reserved for IP option code, length, and pointer. Because IP option data can be used for different functionality (timestamp, strict routing, route, and record), the code field specifies the option type. The length field, oddly enough, states the size of the optional data, which can’t be larger than 40. Finally, the offset pointer field points to the current IP address in the remaining data section, which is rewritten as the packet traverses the Internet. Figure 4-15 demonstrates the offset pointer in action.

There are two types of source routing, both defined in RFC 791:

Loose source routing allows the packet to use any number of intermediate gateways to reach the next address in the route. Strict source routing requires the next address in the source route to be on a directly connected network; if not, the delivery of the packet can’t be completed.

The source route options have a variable length, containing a series of IP addresses and an offset pointer indicating the next IP address to be processed. A source-routed datagram completes its delivery when the offset pointer points beyond the last field and the address in the destination address has been reached.

There is a limit of 40 characters for the router data within the IP options field. With 3 bytes used for the header information and 4 bytes committed for the final host address, there remain only 33 bytes to define loose hops, so 8 IP addresses can be defined in the list of hops (not counting the final destination host).

Source routing vulnerabilities can be exploited by:

Reversing the source route

Circumventing filters and gaining access to internal hosts

If a firewall or gateway reverses the source routing information when sending packets back, you can sniff traffic at one of the hops you defined. In a similar fashion to using sniffer-based spoofed scanning, you can launch scans and probes from potentially trusted hosts (e.g., branch office firewalls) and acquire accurate results.

In the case of Microsoft Windows NT hosts, the circumvention of filters involves manipulating the source routing options information to have an offset pointer set greater than the length of the list of hops and defining an internal host as the last hop (which is then reversed, sending the packet to the internal host). This vulnerability is indexed as SecurityFocus BID 646, accessible at http://www.securityfocus.com/bid/646.

Assessing source-routing vulnerabilities

Todd MacDermid of Syn Ack Labs (http://www.synacklabs.net) has written two excellent tools that can assess and exploit source routing vulnerabilities found in remote networks:

Both tools require libpcap and libdnet to build, and they run quite smoothly in Linux and BSD environments. A white paper written by Todd that explains source routing problems in some detail is also available from http://www.synacklabs.net/OOB/LSR.html.

lsrscan

The lsrscan tool crafts probe packets with specific source routing options to determine exactly how remote hosts deal with source-routed packets. The tool checks for the following two problems:

Whether the target host reverses the source route when sending packets back

Whether the target host can forward source-routed packets to an internal host, by setting the offset pointer to be greater than the number of hops defined in the loose hop list

The basic usage of the tool is as follows:

# lsrscan

usage: lsrscan [-p dstport] [-s srcport] [-S ip]

[-t (to|through|both)] [-b host<:host ...>]

[-a host<:host ...>] <hosts>Some operating systems will reverse source-routed traffic only to ports that are open, so lsrscan should be run against an open port. By default, lsrscan uses a destination port of 80. The source port and source IP addresses aren’t so necessary (lsrscan selects a random source port and IP address) but can be useful in some cases.

The -b option inserts IP

addresses of hops before the user’s host in the source route list.

Likewise, the -a option inserts

specific IP addresses after the user’s host in the list (although

those hosts must support source route forwarding for the scan to

be effective). For more information about the flags and options

that can be parsed, consult the lsrscan

manpage. Example 4-8

shows lsrscan being run

against a network block to identify source routing

problems.

# lsrscan 217.53.62.0/24

217.53.62.0 does not reverse LSR traffic to it

217.53.62.0 does not forward LSR traffic through it

217.53.62.1 reverses LSR traffic to it

217.53.62.1 forwards LSR traffic through it

217.53.62.2 reverses LSR traffic to it

217.53.62.2 does not forward LSR traffic through itBecause some systems reverse the source route, spoofing attacks using lsrtunnel can be performed. Knowing that systems forward source-routed traffic, accurate details of internal IP addresses need to be gained so that port scans can be launched through fragroute to internal space.

lsrtunnel

lsrtunnel spoofs connections using source-routed packets. For the tool to work, the target host must reverse the source route (otherwise the user will not see the responses and be able to spoof a full TCP connection). lsrtunnel requires a spare IP address on the local subnet to use as a proxy for the remote host.

Running lsrtunnel with no options shows the usage syntax:

# lsrtunnel

usage: ./lsrtunnel -i <proxy IP> -t <target IP> -f <spoofed IP>The proxy IP is an unused network address an attacker uses to proxy connections between her host and the target address. The spoofed IP address is the host that appears as the originator of the connection. For additional detail, consult the lsrtunnel manpage.

In this example of lsrtunnel in use, 192.168.102.2 is on the same local

subnet as the host:

# lsrtunnel -i 192.168.102.2 -t 217.53.62.2 -f relay2.ucia.govAt this point, lsrtunnel listens for traffic on the

proxy IP (192.168.102.2). Using

another system on the network, any TCP-based scan or attack

launched against the proxy IP, is forwarded to the target

(217.53.62.2) and appears as if

it originated from relay2.ucia.gov.

Using Specific TCP and UDP Source Ports

When using a tool such as nmap to perform either UDP or TCP port scanning of hosts, it is important to assess responses using specific source ports. Here are four source ports you should use along with UDP, half-open SYN, and inverse FIN scan types:

TCP or UDP port 53 (DNS)

TCP port 20 (FTP data)

TCP port 80 (HTTP)

TCP or UDP port 88 (Kerberos)

Using specific source ports, attackers can take advantage of firewall configuration issues. UDP port 53 (DNS) is a good candidate when circumventing stateless packet filters because machines inside the network need to communicate with external DNS servers, which in turn respond using UDP port 53. Typically, a rule is put in place allowing traffic from UDP port 53 to destination port 53 or anything above 1024 on the internal client machine.

Check Point Firewall-1, Cisco PIX, and other stateful firewalls aren’t vulnerable to these issues (unless grossly misconfigured) because they maintain a state table and allow traffic back into the network only if a relative outbound connection or request has been initiated.

An inverse FIN scan should be attempted when scanning the HTTP service port because a Check Point Firewall-1 option known as fastmode is sometimes enabled for web traffic in high throughput environments (to limit use of firewall processing resources). For specific information regarding circumvention of Firewall-1 in certain configurations, consult the excellent presentation from Black Hat Briefings 2000 by Thomas Lopatic, John McDonald, and Dug Song, titled “A Stateful Inspection of Firewall-1” (available as a Real media video stream and Powerpoint presentation from http://www.blackhat.com/html/bh-usa-00/bh-usa-00-speakers.html).

On Windows 2000 and other Microsoft platforms that can run IPsec, a handful of default exemptions to the IPsec filter exist, including one that allows Kerberos (source TCP or UDP port 88) traffic into the host if the filter is enabled. These default exemptions are removed in Windows Server 2003, but still pose a problem in some environments that rely on filtering at the operating-system kernel level.

With the -g option, nmap can launch a half-open TCP SYN port

scan that uses the source port of 88 against a Windows 2000 server

running IPsec filtering, as shown in Example 4-9.

# nmap -sS -g 88 192.168.102.250

Starting nmap 3.45 ( www.insecure.org/nmap/ )

Interesting ports on kenny (192.168.102.250):

(The 1528 ports scanned but not shown below are in state: closed)

Port State Service

7/tcp open echo

9/tcp open discard

13/tcp open daytime

17/tcp open qotd

19/tcp open chargen

21/tcp open ftp

25/tcp open smtp

42/tcp open nameserver

53/tcp open domain

80/tcp open http

88/tcp open kerberos-sec

135/tcp open loc-srv

139/tcp open netbios-ssn

389/tcp open ldap

443/tcp open https

445/tcp open microsoft-ds

464/tcp open kpasswd5

515/tcp open printer

548/tcp open afpovertcp

593/tcp open http-rpc-epmap

636/tcp open ldapssl

1026/tcp open nterm

2105/tcp open eklogin

6666/tcp open irc-serv

Nmap run completed -- 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 1 secondsecondLow-Level IP Assessment

Tools such as nmap, hping2, and firewalk perform low-level IP assessment. Sometimes holes exist to allow certain TCP services through the firewall, but the expected service isn’t running on the target host. Such low-level network details are useful to know, especially in sensitive environments (e.g., online banking environments), because very small holes in network integrity can sometimes be abused along with larger problems to gain or retain access to target hosts.

Insight into the following areas of a network can be gleaned through low-level IP assessment:

Uptime of target hosts (by analyzing the TCP timestamp option)

TCP services that are permitted through the firewall (by analyzing responses to TCP and ICMP probes)

TCP sequence and IP ID incrementation (by running predictability tests)

The operating system of the target host (using IP fingerprinting)

nmap automatically attempts to calculate target host uptime information by analyzing the TCP timestamp option values of packets received. The TCP timestamp option is defined in RFC 1323; however, many platforms don’t adhere to RFC 1323. This feature often gives accurate results against Linux operating systems and others such as FreeBSD, but your mileage may vary.

Analyzing Responses to TCP Probes

A TCP probe always results in one of four responses. These responses potentially allow an analyst to identify where a connection was accepted, or why and where it was rejected, dropped, or lost:

- TCP SYN/ACK

If a SYN/ACK packet is received, the port is considered open.

- TCP RST/ACK

If a RST/ACK packet is received, the probe packet was either rejected by the target host or an upstream security device (e.g., a firewall with a reject rule in its policy).

- ICMP type 3 code 13

If an ICMP type 3 code 13 message is received, the host (or a device such as a firewall) has administratively prohibited the connection according to an access control list (ACL) rule set.

- Nothing

If no packet is received, an intermediary security device silently dropped it.

nmap returns details of ports that are open, closed, filtered, and unfiltered in line with this list. The unfiltered state is reported by nmap from time to time, depending on the number of filtered ports found. If some ports don’t respond, but others respond with RST/ACK, the responsive ports are considered unfiltered (because the packet is allowed through the filter but the associated service isn’t running on the target host).

hping2 can be used on a port-by-port basis to perform low-level analysis of responses to crafted TCP packets that are sent to destination network ports of remote hosts. Another useful tool is firewalk, which performs filter analysis by sending UDP or TCP packets with specific TTL values. These unique features of hping2 and firewalk are discussed next.

hping2

hping2 allows you to craft and send TCP packets to remote hosts with specific flags and options set. From analyzing responses at a low level, it is often possible to gain insight into the filter configuration at network level. The tool is complex to use, and it has many possible options. Table 4-3 lists the most useful flags for performing low-level TCP assessment.

Here’s a best practice way to use hping2 to assess a specific TCP port:

# hping2 -c 3 -s 53 -p 139 -S 192.168.0.1

HPING 192.168.0.1 (eth0 192.168.0.1): S set, 40 headers + 0 data

ip=192.168.0.1 ttl=128 id=275 sport=139 flags=SAP seq=0 win=64240

ip=192.168.0.1 ttl=128 id=276 sport=139 flags=SAP seq=1 win=64240

ip=192.168.0.1 ttl=128 id=277 sport=139 flags=SAP seq=2 win=64240In this example, a total of three TCP SYN packets are sent to

port 139 on 192.168.0.1 using the

source port 53 of the host (some firewalls ship with a configuration

that allows DNS traffic through the filter with an any-any rule, so

it is sometimes fruitful to use a source port of 53).

Following are four examples of hping2 that generate responses in line with the four states discussed previously (open, closed, blocked, or dropped).

TCP port 80 is open:

# hping2 -c 3 -s 53 -p 80 -S google.com

HPING google.com (eth0 216.239.39.99): S set, 40 headers + 0 data

ip=216.239.39.99 ttl=128 id=289 sport=80 flags=SAP seq=0 win=64240

ip=216.239.39.99 ttl=128 id=290 sport=80 flags=SAP seq=1 win=64240

ip=216.239.39.99 ttl=128 id=291 sport=80 flags=SAP seq=2 win=64240TCP port 139 is closed or access to the port is rejected by a firewall:

# hping2 -c 3 -s 53 -p 139 -S 192.168.0.1

HPING 192.168.0.1 (eth0 192.168.0.1): S set, 40 headers + 0 data

ip=192.168.0.1 ttl=128 id=283 sport=139 flags=R seq=0 win=64240

ip=192.168.0.1 ttl=128 id=284 sport=139 flags=R seq=1 win=64240

ip=192.168.0.1 ttl=128 id=285 sport=139 flags=R seq=2 win=64240TCP port 23 is blocked by a router ACL:

# hping2 -c 3 -s 53 -p 23 -S gw.example.org

HPING gw (eth0 192.168.0.254): S set, 40 headers + 0 data

ICMP unreachable type 13 from 192.168.0.254

ICMP unreachable type 13 from 192.168.0.254

ICMP unreachable type 13 from 192.168.0.254TCP probe packets are dropped in transit:

# hping2 -c 3 -s 53 -p 80 -S 192.168.10.10

HPING 192.168.10.10 (eth0 192.168.10.10): S set, 40 headers + 0 datafirewalk

Mike Schiffman and Dave Goldsmith’s firewalk utility (Version 5.0 at the time of writing) allows assessment of firewalls and packet filters by sending IP packets with TTL values set to expire one hop past a given gateway. Three simple states allow you to determine if a packet has passed through the firewall or not:

If an ICMP type 11 code 0 (TTL exceeded in transit) message is received, the packet passed through the filter, and a response was later generated.

If the packet is dropped without comment, it was probably done at the gateway.

If an ICMP type 3 code 13 (communication administratively prohibited) message is received, a simple filter such as a router ACL is being used.

If the packet is dropped without comment, this doesn’t necessarily mean that traffic to the target host and port is filtered. Some firewalls know that the packet is due to expire and send the expired message whether the policy allows the packet or not.

firewalk works effectively against hosts in true IP routed environments, as opposed to hosts behind firewalls using network address translation (NAT). I recommend reading the firewalk white paper written by Mike Schiffman and Dave Goldsmith, available from http://www.packetfactory.net/projects/firewalk/firewalk-final.pdf.

Example 4-10 shows firewalk being run against a host to assess filters in place for a selection of TCP ports (21, 22, 23, 25, 53, and 80). The utility requires two IP addresses: the gateway (gw.test.org in this example) and the target (www.test.org in this example) that is behind the gateway.

# firewalk -n -S21,22,23,25,53,80 -pTCP gw.test.org www.test.org

Firewalk 5.0 [gateway ACL scanner]

Firewalk state initialization completed successfully.

TCP-based scan.

Ramping phase source port: 53, destination port: 33434

Hotfoot through 217.41.132.201 using 217.41.132.161 as a metric.

Ramping Phase:

1 (TTL 1): expired [192.168.102.254]

2 (TTL 2): expired [212.38.177.41]

3 (TTL 3): expired [217.41.132.201]

Binding host reached.

Scan bound at 4 hops.

Scanning Phase:

port 21: A! open (port listen) [217.41.132.161]

port 22: A! open (port not listen) [217.41.132.161]

port 23: A! open (port listen) [217.41.132.161]

port 25: A! open (port not listen) [217.41.132.161]

port 53: A! open (port not listen) [217.41.132.161]

port 80: A! open (port not listen) [217.41.132.161]

Scan completed successfully.The tool first performs an effective traceroute to the target host in order to calculate the number of hops involved. Upon completing this initial reconnaissance, crafted TCP packets are sent with specific IP TTL values. By analyzing the responses from the target network and looking for ICMP type 11 code 0 messages, an attacker can reverse-engineer the filter policy of gw.test.org.

Passively Monitoring ICMP Responses

As port scans and network probes are launched, you can passively monitor all traffic using ethereal or tcpdump. Often, you will see ICMP responses from border routers and firewalls, including:

ICMP TTL exceeded (type 11 code 0) messages, indicating a routing loop

ICMP administratively prohibited (type 3 code 13) messages, indicating a firewall or router that rejects certain packets in line with an ACL

These ICMP response messages give insight into the target network’s setup and configuration. It is also possible to determine IP alias relationships in terms of firewalls performing NAT and other functions to forward traffic to other hosts and devices (for example, if you are probing a public Internet address but see responses from a private address in your sniffer logs).

IP Fingerprinting

Various operating platforms have their own interpretations of IP-related standards when receiving certain types of packets and responding to them. By analyzing responses from Internet-based hosts carefully, attackers often can guess the operating platform of the target host via IP fingerprinting, usually by assessing and sampling the following IP responses:

TCP FIN probes and bogus flag probes

TCP sequence number sampling

TCP WINDOW sampling

TCP ACK value sampling

ICMP message quoting

ICMP ECHO integrity

Responses to IP fragmentation

IP TOS (type of service) sampling

Originally, tools such as cheops and queso were developed specifically to guess target system operating platforms; however, the first publicly available tool to perform this was sirc3, which simply detected the difference between BSD-derived, Windows, and Linux TCP stacks.

Today, nmap performs a large number of IP fingerprinting tests to

guess the remote operating platform. To enable IP fingerprinting when

running nmap, simply use the

-O flag in combination with a scan

type flag such as -sS, as shown in

Example 4-11.

# nmap -O -sS 192.168.0.65

Starting nmap 3.45 ( www.insecure.org/nmap/ )

Interesting ports on 192.168.0.65:

(The 1585 ports scanned but not shown below are in state: closed)

Port State Service

22/tcp open ssh

25/tcp open smtp

53/tcp open domain

80/tcp open http

88/tcp open kerberos-sec

110/tcp open pop-3

135/tcp open loc-srv

139/tcp open netbios-ssn

143/tcp open imap2

389/tcp open ldap

445/tcp open microsoft-ds

464/tcp open kpasswd5

593/tcp open http-rpc-epmap

636/tcp open ldapssl

1026/tcp open LSA-or-nterm

1029/tcp open ms-lsa

1352/tcp open lotusnotes

3268/tcp open globalcatLDAP

3269/tcp open globalcatLDAPssl

3372/tcp open msdtc

Remote OS guesses: Windows 2000 or WinXP

Nmap run completed -- 1 IP address (1 host up)TCP Sequence and IP ID Incrementation

If TCP sequence numbers are generated in a predictable way by the target host, then blind spoofing and hijacking can occur (although this is usually limited to internal network spaces). Older Windows operating platforms suffer from this because the sequence numbers are simply incremented instead of randomly generated.

If the IP ID value is incremental, the host can be used as a third party to perform IP ID header scanning as discussed in Section 4.2.3.4. IP ID header scanning requires the ID values returned from the third party to be incremental so that accurate scan results can be gathered.

Example 4-12 shows

nmap being run in verbose mode

(-v) with TCP/IP fingerprinting

(-O). Setting both options shows

the results of both TCP and IP ID sequence number predictability

tests.

# nmap -v -sS -O 192.168.102.251

Starting nmap 3.45 ( www.insecure.org/nmap/ )

Interesting ports on cartman (192.168.102.251):

(The 1524 ports scanned but not shown below are in state: closed)

Port State Service

25/tcp open smtp

53/tcp open domain

8080/tcp open http-proxy

Remote OS guesses: Windows 2000 RC1 through final release

TCP Sequence Prediction: Class=random positive increments

Difficulty=15269 (Worthy challenge)

IPID Sequence Generation: Incremental

Nmap run completed -- 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 1 secondNetwork Scanning Recap

Different IP network scanning methods allow you to test and effectively identify vulnerable network components. Here is a list of effective network scanning techniques and their applications:

- ICMP scanning and probing

By launching an ICMP ping sweep, you can effectively identify poorly protected hosts (as security conscious administrators filter inbound ICMP messages) and perform a degree of operating-system fingerprinting and reconnaissance by analyzing responses to the ICMP probes.

- Half-open SYN flag TCP port scanning

A SYN port scan is often the most effective type of port scan to launch directly against a target IP network space. SYN scanning is extremely fast, allowing you to scan large networks quickly.

- Inverse TCP port scanning

Inverse scanning types (particularly FIN, Xmas, and NULL) take advantage of idiosyncrasies in certain TCP/IP stack implementations. This scanning type isn’t effective when scanning large network spaces, although it is useful when testing and investigating the security of specific hosts and small network segments.

- Third-party TCP port scanning

Using a combination of vulnerable network components and TCP spoofing, third-party TCP port scans can be effectively launched. Scanning in this fashion has two benefits: hiding the true source of a TCP scan and assessing the filters and levels of trust between hosts. Although time consuming to undertake, third-party scanning is extremely useful when applied correctly.

- UDP port scanning

Identifying accessible UDP services can be undertaken easily only if ICMP type 3 code 3 (destination port unreachable) messages are allowed back through filtering mechanisms that protect target systems. UDP services can sometimes be used to gather useful data or directly compromise hosts (the DNS, SNMP, TFTP, and BOOTP services in particular).

- IDS evasion and filter circumvention

Intrusion detection systems and other security mechanisms can be rendered ineffective by using multiple spoofed decoy hosts when scanning or by fragmenting probe packets using nmap or fragroute. Filters such as firewalls, routers, and even software (including the Microsoft IPsec filter) can sometimes be bypassed using specific source TCP or UDP ports, source routing, or stateful attacks.

Network Scanning Countermeasures

Here is a checklist of countermeasures to use when considering technical modifications to networks and filtering devices to reduce the effectiveness of network scanning and probing undertaken by attackers:

Filter inbound ICMP message types at border routers and firewalls. This forces attackers to use full-blown TCP port scans against all of your IP addresses to map your network correctly.

Filter all outbound ICMP type 3 unreachable messages at border routers and firewalls to prevent UDP port scanning and firewalking from being effective.

Consider configuring Internet firewalls so that they can identify port scans and throttle the connections accordingly. You can configure commercial firewall appliances (such as those from Check Point, NetScreen, and WatchGuard) to prevent fast port scans and SYN floods being launched against your networks. On the open source side, there are many tools such as portsentry that can identify port scans and drop all packets from the source IP address for a given period of time.

Assess the way that your network firewall and IDS devices handle fragmented IP packets by using fragtest and fragroute when performing scanning and probing exercises. Some devices crash or fail under conditions in which high volumes of fragmented packets are being processed.

Ensure that your routing and filtering mechanisms (both firewalls and routers) can’t be bypassed using specific source ports or source-routing techniques.

If you house publicly accessible FTP services, ensure that your firewalls aren’t vulnerable to stateful circumvention attacks relating to malformed PORT and PASV commands.

If a commercial firewall is in use, ensure the following:

The latest service pack is installed.

Antispoofing rules have been correctly defined, so that the device doesn’t accept packets with private spoofed source addresses on its external interfaces.

Fastmode services aren’t used in Check Point Firewall-1 environments.

Investigate using inbound proxy servers in your environment if you require a high level of security. A proxy server will not forward fragmented or malformed packets, so it isn’t possible to launch FIN scanning or other stealth methods.

Be aware of your own network configuration and its publicly accessible ports by launching TCP and UDP port scans along with ICMP probes against your own IP address space. It is surprising how many large companies still don’t properly undertake even simple port-scanning exercises.

[1] URLs for tools in this book are mirrored at the O’Reilly site, http://examples.oreilly.com/networksa/tools.

Get Network Security Assessment now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.