Chapter 7. Online Deliberation and Civic Intelligence

In addition to the prosaic—but nevertheless crucial—tasks related to the everyday necessities of staying alive, people and communities must also face—at least indirectly—a wide range of staggering challenges, such as pandemics, environmental degradation, climate change, starvation, war, militarism, terrorism, and oppression. Unfortunately, many of the world’s inhabitants are very young or have other good reasons (such as extreme poverty) for their lack of opportunity, motivation, knowledge, or skills to face these challenges.

This, in essence, is the situation in which we find ourselves: a world seriously out of order and a world society that for many reasons may be less equipped to deal with these challenges than it needs to be. This is precisely the issue that the concept of “civic intelligence” is intended to highlight: will we be smart enough, soon enough?

Definitions and Assertions

Before we go any further, it seems best to present the four concepts that are at the core of this chapter—civic intelligence, democracy, open government, and deliberation—and show how they are related to each other.

Civic intelligence is a form of collective intelligence directed toward shared challenges.[110] Its presence or absence will determine how effectively these challenges are met. Civic intelligence exists to a greater or lesser degree in all societies.

Because the government and other elite groups are not capable of addressing the problems we’re faced with, a deeper form of civic intelligence built upon rich interactions between citizens distributed throughout the world will be required. This intelligence won’t emerge solely from a series of votes or other algorithmic techniques no matter how clever they are.

Thinking in terms of civic intelligence helps us to pose an interesting thought experiment: as the challenges facing us become more complex, numerous, fierce, and unpredictable, do we have the necessary collective intelligence to meet them?

Democracy in its ideal sense is the form of political organization that most closely embodies civic intelligence.

Many people seek a precise definition of democracy to guide their thinking in this area. But the meanings of social concepts are not chiseled in granite. In its most general form, democracy means governance by the people. Democracy takes different shapes in different contexts. Democracy is also defined by inclusive and transparent processes, although access to these processes is sometimes blocked and the processes themselves are often corrupted by the political or economic elite.

Many descriptions of democracy focus on the outcome and the formalized process for getting there. One common aspect of arguments in support of democracy is the prospect of an outcome that is better because of more involvement in its creation, almost exclusively through voting. Rarely heard is the idea that participation in a democratic process can actually make individuals more qualified for citizenship and hence can build a type of civic intelligence that is better for the entire commonwealth. This is the case that John Dewey, the prominent American public intellectual, developed: that democracy should be seen as a way of life, not as a duty to be duly discharged every four or so years.

Democracy exists at the intersection of practicality and idealism. As a society attempts to move closer to an ideal democratic state, it generally becomes more difficult to maintain its practical nature. On some level, democracy, like any system, must be implemented (and maintained); it consists of institutional processes and material machinery and uses resources. Is democracy more expensive in terms of resource investment (including time and money) than other forms of government? How much is democracy worth?

Open government, an idea whose meaning is currently being constructed, offers a provocative set of ideas for reconstructing government in ways that could increase and improve the abilities of democratic societies to deal effectively, sustainably, and equitably with its issues. In other words, open government, if implemented thoughtfully, could improve our democracy and our civic intelligence while keeping the costs to acceptable and appropriate levels.

Some people take comfort from the seemingly solid ideological position that asserts that “less” government is always good. This position tacitly acknowledges that other institutions (e.g., large corporations) will assume more power (though likely of a different kind). President Obama rightly reframes that question not as a choice between less or more, but between better or worse government. And if the goal isn’t necessarily less government, the goal is certainly not no government. After all, Road Warrior makes a better movie than an exemplar for an ideal society. The goal is to change the nature of governance, particularly the relationship of “ordinary citizens” to the government, not the abandonment of social norms. The main reason that governance should be opened up to “ordinary” people is not because it’s more just. And while opened-up governance is likely to be less corrupt than opaque governance, opened-up governance is simply the only feasible way to bring adequate resources (such as local knowledge and creative problem-solving capabilities) to bear on the challenges that we now face.

Open government without a corresponding increase in an informed, concerned, and engaged citizenry is no solution; in fact, it makes no sense. Paradoxically, the first place to focus attention when attempting to develop a more open government is on the people being governed. Open government might mean totally distributed governance; the end of the government as the sole governing body. For that reason, one of the most critical questions to ask is what capabilities and information do citizens need most to meet the challenges they face?

Deliberation is a process of directed communication whereby people discuss their concerns in a reasonable, conscientious, and open manner, with the intent of arriving at a decision. Deliberation takes different forms in different societal contexts and involves participants of myriad interests, skills, and values. It is generally more formal than collaboration or discussion. While some people may balk at this “tyranny of structure,” it is the shared awareness of the structure that provides legitimacy and impetus toward meaningful discussion and satisfactory decision making.

Deliberation occurs when people with dissimilar points of view exchange ideas with the intent of coming to an agreement. Less successful outcomes—that are not failures—include agreeing to disagree, or even attaining a better understanding of other viewpoints. At any rate, deliberation is distinct from other communication modalities such as individual reflection, repeating and reinforcing shared viewpoints, acquiring a viewpoint solely through exposure to mass media, or working to defeat a person, idea, or enterprise, not via merits of one’s own argument or the lack of merits of the other, but by any (nonviolent) means necessary, including character assassination and lying.

Significantly, deliberation is an important capability within the more general capability of civic intelligence. After a decision is made, there is presumably an opinion or frame, activity or plan that is shared by a larger number of people. The intended product of deliberation is a more coherent vision of the future. It can also result in increased solidarity within a group.

The Context of Deliberation

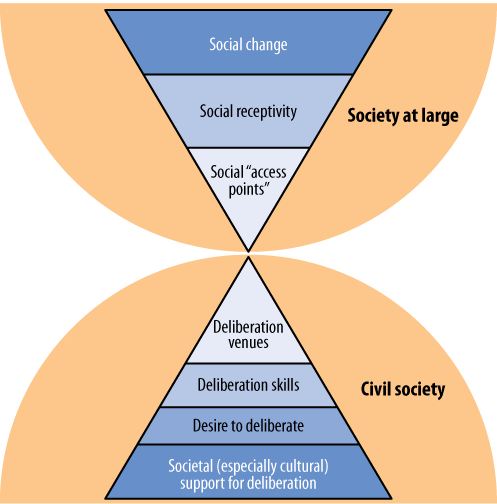

Deliberation, of course, makes sense only within a social context and is meaningful only when it’s actually linked with multiple “levels” of society, including, ultimately, the potential to be a factor in social change. This “context of deliberation” can be depicted visually in an hourglass form (see Figure 7-1). Although somewhat abstract, this depiction illustrates the necessary social attributes of a society in which deliberation can be said to function adequately. (And a society without deliberation can’t really be considered a democracy society.) The lower half of the hourglass shows that deliberation depends on the desire and the ability of the people to deliberate, and that the venues within which people can deliberate are available. The upper half of the hourglass shows that deliberation is an instrument of democracy only when the possibility of interacting with—and influencing—the rest of society exists. This means that “social access points” such as newspapers, educational systems, public forums, government institutions, and the like that can help carry the content and the decisions of a deliberative body to a wider audience in society also exist. This in turn relies on the receptivity of people and institutions to actually adopt the findings of the deliberation.

Democracy, Deliberation, and the Internet

Since its inception, the Internet has been touted as a medium with revolutionary potential for democratic communication. Although other media including broadcast television and radio have not lived up to their democratic potential, it is too early to dismiss the Internet as being solely a tool of the powerful. The Internet is actually a “meta-medium” that can be used to host a variety of traditional media as well as new hybrids.[111] Its extreme mutability, coupled with the potential of establishing communication channels between any two (or more) people on Earth, accounts for its enormous—and radical—potential for democratic communication. Certainly, civil society recognizes this and has been extraordinarily creative in using the Internet for positive social change.[112] On the other hand, many people don’t have full access to the Internet or have the time to access it. These vast differences help provide another dimension to the have/have-not continuum, and to the degree that governance moves into the digital realm this distance becomes a measure of digital disenfranchising.

Although a very large number of approaches to communication exist in cyberspace, one critical function—deliberation—seems to have been forgotten. Groups need to deliberate, and for many reasons they aren’t always able to meet face to face. In fact, as many problems that we face are global in nature, the groups that are affected by the problems or who otherwise are compelled to address the problems must reach across local boundaries to address their shared concerns. The need for computer support for online deliberation can be shown by the fact that many online discussions seem to have no resolution at all; they often dribble off into nothingness, leaving more frustration than enlightenment in their wake. Worse, many online discussions degenerate into “flame wars” where online feuds make it difficult for the nonfeuders to get any work done.

Online Civic Deliberation

Online deliberation is the term for a network-based (usually Internet) computer application that supports the deliberative process. People have been thinking about how computer systems could be used for collaboration, negotiation, and deliberation for some time. Douglas Engelbart’s work in this field was pioneering.[113] At present, few examples exist, although this number is slowly increasing. There have been many innovative deliberative approaches involving face-to-face interactions. These include the consensus conferences developed by the Danish Board of Technology (DBT), deliberative polling,[114] and Citizen Summits (e.g., http://americaspeaks.org). The DBT is currently coordinating the Worldwide Views on Global Warming project with approximately 50 countries to engage their citizens in deliberation about climate change: other deliberative projects are also targeting climate change, including MIT’s Collaboratorium[115] and the Global Sensemaking project. While I do not have the space here to discuss them, people have experimented with video teleconferencing, live television, special-purpose-outfitted rooms, and so forth to assist deliberative processes. These efforts, however positive some of the results may have been, are often stymied by high costs and other challenges and have yet to be adopted widely.

There are several reasons for the relatively small effort in this area. For one thing, deliberation applications are difficult to design and implement. This is one of the main reasons why few applications are available. (Of course, this reflects the “chicken and egg” nature of this situation. If the applications don’t exist, people won’t use them. If people don’t use them, programmers won’t develop them….) For this reason, we must develop deliberative systems in a co-evolutionary way, working cooperatively with the communities that are most interested in using them. Moreover, there is seemingly little money to be made with online deliberation. E-commerce, for example, has larger target populations, is easier to program, and is more lucrative. The difficulty of demonstrating the benefits of deliberation using current approaches may contribute to this lack of support.

Deliberation is also difficult to do. It is time-consuming, it is confusing in many cases (due to content as well as the formal nature of the process), and the “payoff” is often perceived by would-be participants to be far less than the effort expended. For this reason, the percentage of people who actively engage in deliberation in a regular civic or formal sense is very low—even lower than voting, a discouraging fact considering voting’s low bar and its declining rates of participation. A third reason is that government bodies from the smallest towns to the highest national and supranational (e.g., the European Union) levels seem unable (or, perhaps more accurately, unwilling) to support public deliberation in a genuine way, whether it’s online or not.

The hypothesis is that if it were easier to participate in deliberative sessions and—most importantly—the results of their efforts were perceived as worthwhile, citizen deliberation would become more popular. If deliberation actually was incorporated into governance and became valued by society at the same time, a closer approximation of the vision of democracy as a way of life envisioned by John Dewey would be achieved.

Support for Online Civic Deliberation

Development of a network-based application that could help nonprofit, community-based organizations convene effective deliberative meetings when members couldn’t easily get together for face-to-face meetings could be very useful. While the goal is not to replace face-to-face meetings, it is hypothesized that the use of an online system could potentially help organizations with limited resources. Ideally, the technology would increase the organization’s effectiveness while reducing the time and money spent on its deliberative meetings. In general, judging the success of any approach to deliberation includes considering access to the process, the efficacy of the process (including individual involvement and the process as a whole), and integration with the social context (including legal requirements, etc.). Of course, these criteria overlap to some degree and influence each other.

Motivated by a long-term desire to employ computing technology for social good, particularly among civil society groups who are striving to create more “civic intelligence” in our society, I proposed that Robert’s Rules of Order could be used as a basis for an online deliberation system.[116] The selection of Robert’s Rules of Order was supported by its widespread use—at least in the United States—and the formalized definitions of its rules. Robert’s Rules of Order is one version of the familiar form of deliberation often known as parliamentary procedure. Proposals are put forward to the assembly with motions (“I move that we hire Douglas Schuler as our executive director”) that must be affirmed (“seconded”) by another person in the assembly before the proposal can be discussed, possibly amended, and voted on (or tabled—dismissed at least temporarily) by the assembly.

Robert’s Rules of Order is a type of “protocol-based cooperative work” system. It is related to Malone’s “semi-structured messages” work[117] and the work done by Winograd and Flores[118] (which was built on the “speech act” work of John Austin.[119]) Those examples all employ “typed messages.” The message “type” is, in effect, a descriptor of the message content, and because it is discrete it is more easily handled by computer applications than natural language. There are several reasons why a strict regimen over communication may be imposed. Generally, this is done is cases where there is contention for resources. In the case of deliberation, the scarcest resource is the time available for speaking. This is generally true in situations when explicit objectives and/or formal constraints are placed upon the venue—in a courtroom or with a legislative body, for example.

E-Liberate is created

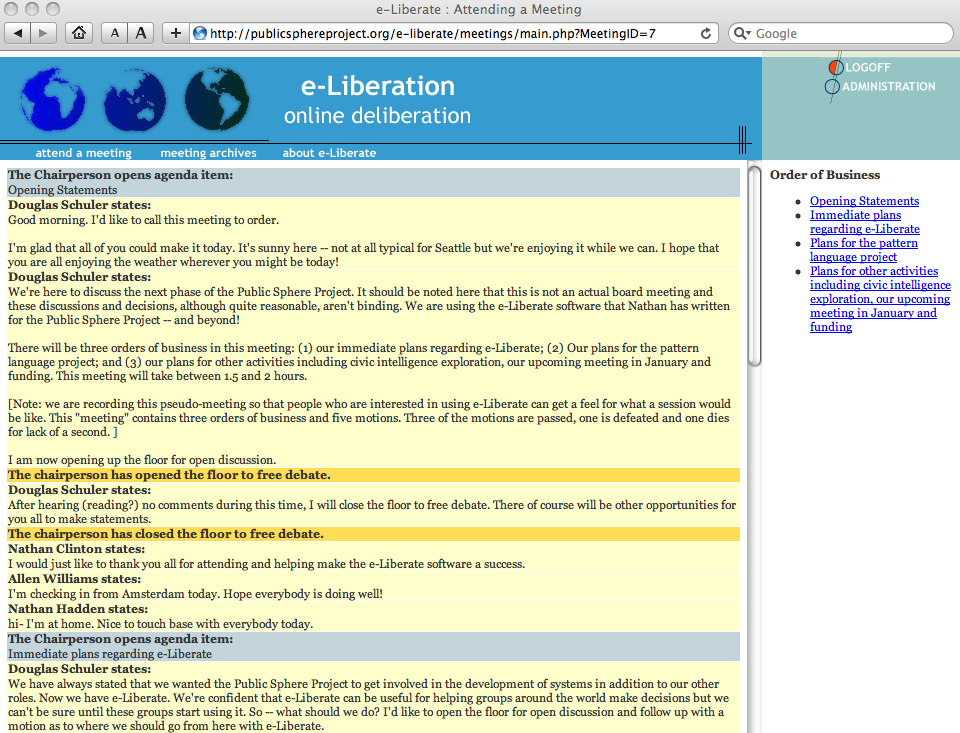

In 1999, a team of students at The Evergreen State College developed the first prototype of an online version of Robert’s Rules of Order that was ultimately named e-Liberate (which rhymes with the verb deliberate; see Figure 7-2). The objective of e-Liberate was to move beyond chat, premature endings, and unresolved digressions. The initial objective was to support groups that were already deliberating and to try to mimic their existing processes—as closely as possible. This approach was intended to minimize disruption by integrating the online system as unobtrusively as possible into their work lives. E-Liberate is intended to be easy to use for anybody familiar with Robert’s Rules of Order.

Online deliberation offers some advantages and disadvantages over face-to-face deliberation. The system employs a straightforward user interface which is educational as well as facilitative. The interface shows, for example, only the legal actions that are available to the user at that specific time in the meeting. (For example, a user can’t second a motion that she submitted or when there is no motion on the table to second.) Also, at any time during a session an “about” button can be clicked that presents an explanation of what each particular action will accomplish, thus providing useful cues that aren’t available in face-to-face meetings. In addition, the software checks if meeting quorums exist, conducts voting on motions, and automatically records (and archives) the minutes. See http://publicsphereproject.org/e-liberate/demo.php for a transcript of an entire sample meeting.

The developers of e-Liberate have begun working with groups that are interested in using the system to support actual meetings. We are enthusiastic about the system but are well aware that the current system is likely to have problems that need addressing. It is for that reason that we continue to host meetings with groups and gather feedback from attendees. We plan to study a variety of online meetings in order to adjust the system and to develop heuristics for the use of the system. Our plan is to make e-Liberate freely available for online meetings and to release the software under a free software license.

For many years, Fiorella de Cindio and her group at the University of Milan have been developing community collaborative tools in association with the Milan Community Network (Rete Civica di Milano, or RCM) effort. The openDCN approach is to work toward an integrated ensemble of online services that is useful for community members and citizens.[120] The evolving environment builds on the idea of spaces to organize these services.[121] Thus, the community space supports discussion, brainstorming, the City Map application, and other capabilities; the deliberation space supports interactions that are more structured and formal; and the information space links the other two spaces in a variety of ways. The openDCN effort is informed by theory but always with the objective of promoting effective, inclusive, and widespread citizen participation. The openDCN developers created a deliberation module that was inspired by e-Liberate but omits some aspects of Robert’s Rules based on usability studies. This basic module has been tested in several locations around Italy, generally around Agenda 21 participatory urban planning activities. The results have been mixed, but the work has helped bring many potential challenges and opportunities to light. A change in the leadership of a municipal administration, for example, is likely to result in profound changes, often withdrawal of support. Other significant projects include the georeferenced discussion used on a site sponsored by the South African Ministry of Communication for the 2010 soccer world championship (http://www.e-soccer.opendcn.org/). The informed discussion has been used to support a group of friends who were together in the university during the years around 1968 and want to maintain their friendship online (http://www.68cittastudi.retecivica.milano.it/), while the citizens consultation has been used by the Milan School Trade Unions to collect feedback from workers on a negotiated agreement (http://flc-cgil.retecivica.milano.it/). Additionally, openDCN has been used to support teaching and learning in the virtual community course at the university (http://jlidcncv.lic.dico.unimi.it/ and http://desire.dico.unimi.it/).

Findings and Issues

Our experience with online deliberative systems is limited. What follows is a discussion of issues that the developers of any deliberative system should address.

Role of the Chair

The first set of issues is related to the role of chair, which Robert’s Rules of Order explicitly specifies for every meeting. The specific role of the person so designated includes enforcing “rules relating to debate and those relating to order and decorum,” determining when a rule is out of order and to “expedite business in every way compatible with the rights of members.”[122] These responsibilities apparently rule out a meeting conducted solely among peers. The main reason that a chair is needed at all is due to the fact that the rules alone won’t suffice. There are a variety of situations in which the chair’s input is needed, notably when human judgment is required. Another reason that Robert called upon the services of a chair in his deliberative universe is that meeting attendees may attempt to “game” the system by invoking rules, which although strictly legal, violate the spirit of the meeting. We initiated a form of “auto-chair” in e-Liberate after we ascertained that the chair could actually be an impediment to progress and seemed to be less necessary in the online environment—at least in some situations. When an attendee requests the floor, he is automatically “recognized” by the automated proxy of the chair.

Distributed Meeting Attendees

A second set of issues is introduced when meeting attendees are unseen and distributed. These issues arise when a process that is used in face-to-face environments is adapted to be used in an online environment. For example, how do we know when a quorum is present? This is part of the larger issue of how we know who’s online. Establishing the identity of a person who is interacting, sight unseen, via the Internet is important and is certainly not trivial. In some cases—as in online voting—there are opportunities for fraud that may sometimes prove irresistible. We also would like to know whether, for example, members are offline by choice or whether they want to participate but are unable to connect. And if they’re not connected and/or not paying attention to the meeting at any given time, does that mean that they’re not in attendance and, consequently, a quorum may no longer exist?

Social Environment Requirements

The third set of issues is related to the legal and other aspects of the social environment in which the system operates. In addition to establishing whether a quorum exists, a variety of other requirements include the timely distribution of the notice of the meeting, who can attend, and what type of access must exist for members and must be translated in suitable ways into the digital medium. All of these issues are interrelated and influence each other in obvious and subtle ways. For example, since attendees are no longer at a single shared location, where they would be (presumably) attending solely to the business of the assembly, the question of meeting duration comes up. Should meetings be relatively intense affairs where all attendees are interacting and business is conducted in one or two hours or should/could the meeting be more leisurely, perhaps stretching over one or two weeks? The distribution of attendees across time zones highlights a variety of “problems” that humankind’s Earth-based orientation and social institutions (such as the “workday”, the “workweek,” and family obligations) place in the way of Internet-enabled “always-on” opportunities. These problems add considerable complexity to an already complex undertaking, and for now it suffices to say that addressing these issues will require social as well as technological approaches. Finally, we can only raise the issue of how well e-Liberate performs when used by larger groups. The only way to understand and learn about that is to host meetings with larger numbers of people—50, 100, 1,000—and observe the results and interview the participants.

E-Liberate’s Role

At present, e-Liberate supports online deliberative meetings, discrete sessions that aren’t linked in any way to each other. But deliberation is an ongoing process—not a sporadic, context-free occurrence that has neither history nor consequences. This fact suggests, among other things, the need to integrate deliberative technology with other collaborative technology such as brainstorming or collaborative editing. It is hypothesized that developing software that could support a variety of protocols, along with the ability to inspect and modify the rule base, would make new deliberative projects plausible without necessarily changing the functionality of the basic Robert’s Rules core. It may be possible to develop a variety of “plug and play” modules that could support exploration in the area of “deliberation in the large” in which individual meetings or sessions (“deliberation in the small”) are linked. The ongoing nature of deliberation also suggests that an online tool that helps maintain institutional memory would be especially useful (including the retrieval of agenda items that had been postponed in prior meetings). In many collective enterprises, it is common to break the larger group into smaller working, distributed subsets such as committees or consortia, and the system should support that.

There are also several capabilities related to integration with other services such as email, fax, videoconferencing, and so forth. Invitations and other notices are already sent electronically to e-Liberate participants and there are other times when email communication should be invoked. We also plan to look into document sharing (e.g., the organization’s bylaws) among participants and support for image presentation during meetings.

Finally, as I alluded to earlier, we live in an era in which problems aren’t always confined to one country. The need for international and other cross-border initiatives in which the participants are not elites is critical. The expression “deliberation in the small” can be used to describe a single meeting. Although a single meeting is the foundation of deliberative discourse, it’s only a molecule in the universe of social learning, or what could be called deliberation in the large.

Addressing the broader issues of deliberation in the large can be faced in several ways, from a piecework bottom-up approach, linking, for example, environmental groups in some way, perhaps via an e-Liberate-like system, perhaps not. The other, somewhat orthogonal, approach is to design and implement (and evaluate and critique, etc.) new systems that explicitly address this issue in a more top-down way. Our approach readily combines both approaches and allows for others not yet identified. We are proposing a loosely linked, collaborative enterprise that combines both theoretical and applied research, information and communication technology (ICT) design and implementation, public and popular education, and policy work. We are looking into deliberation in the large as an important thought experiment that should be taken up in a broad social dialog.[123] Part of this is related to inherent rights of people (to communicate, deliberate, participate, etc.), and part of this is related to the necessity of global communications on issues such as climate change.

Conclusion

The online environment offers many opportunities for collective problem solving. Online deliberation (especially in conjunction with other collaborative approaches) has immense potential whose surface is only now being scratched. Although deliberation is not as easy to do as, say, online shopping, it is a cornerstone of democracy and of the civic intelligence required in the twenty-first century.

Currently, there are few opportunities for individuals to help address shared problems. We believe that focusing on civil society—both its organized and its unorganized constituents—is a rich, rewarding, and deserving area for multisector collaborative ventures. The time is ripe for loosening the restrictive boundaries between institutional bodies and other groups of people worldwide: the current governors must be willing to share or abandon some of the power they currently hold, while the people must be willing to assume increased responsibility for governing tasks, thus becoming more fully realized citizens.

A host of risks are associated with these deliberative proposals. Yet the risk of not acting is the most dangerous. Focusing attention on online deliberation presupposes a faith, partially supported by evidence, which states that humans of diverse social stations can deliberate together. We may yet employ our vast technology to the task of obliterating ourselves and life on earth. This possibility should surprise no one: throughout history, humankind has exhibited an enthusiastic genius for establishing hells on earth that surpass the misery of those conceived by our poets, artists, and theologians. On the other hand, the ability to deliberate together may be our most powerful—yet neglected—natural resource. And in our embrace of open governance, we may discover that it is the key to civic intelligence.

I want to thank Fiorella de Cindio for many helpful suggestions with this chapter and for many fruitful discussions and collaborations over the years.

About the Author

Douglas Schuler is president of the Public Sphere Project and a member of faculty at The Evergreen State College. Trained in computer science and software engineering, Douglas has been working on the borderlines of society and technology for more than 20 years. He has written and coedited several books, including New Community Networks: Wired for Change (Addison-Wesley, 1996; http://www.publicsphereproject.org/ncn/) and Liberating Voices: A Pattern Language for Communication Revolution (MIT Press, 2008), a civic intelligence undertaking with 85 contributors (http://www.publicsphereproject.org/patterns/).

[110] “Cultivating Society’s Civic Intelligence: Patterns for a New ‘World Brain’,” Douglas Schuler, Community Informatics, Leigh Keeble and Brian D. Loader (eds.), Routledge, 2001. Liberating Voices: A Pattern Language for Communication Revolution, Douglas Schuler, MIT Press, 2008.

[111] “Community Computer Networks: An Opportunity for Collaboration Among Democratic Technology Practitioners and Researchers,” Douglas Schuler, Technology and Democracy: User Involvement in Information Technology, David Hakken and Knut Haukelid (eds.), Centre for Technology and Culture, University of Oslo, 1997.

[112] “Appropriating the Internet for Social Change: Towards the strategic use of networked technologies by transnational civil society organizations,” Mark Surman and Katherine Reilly, New York: Social Sciences Research Council Information Technology and International Cooperation Program, 2003.

[113] “Coordinated Information Services for a Discipline- or Mission-Oriented Community”, Douglas Engelbart, 1972.

[114] “Experimenting with a democratic ideal: Deliberative polling and public opinion,”James Fishkin and Robert Luskin, Acta Politica, Vol. 40, Number 3, 2005: 284–298.

[115] “Supporting Collaborative Deliberation Using a Large-Scale Argumentation System: The MIT Collaboratorium,” Mark Klein and Luca Iandoli, Directions and Implications of Advanced Computing: Conference on Online Deliberation, Todd Davies and Seeta Peña Gangadharan (eds.), San Francisco: Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility, 2008.

[116] “A Civilian Computing Initiative: Three Modest Proposals,” Douglas Schuler, Directions and Implications of Advanced Computing, Ablex Publishing, 1989. “Cultivating Society’s Civic Intelligence: Patterns for a New ‘World Brain’,” Douglas Schuler, Community Informatics, Leigh Keeble and Brian D. Loader (eds.), Routledge, 2001. New Community Networks: Wired for Change, Douglas Schuler, Addison-Wesley, 1996. Robert’s Rules of Order, Newly Revised, Henry Robert, Perseus Books, 1990. “Online Civic Deliberation and E-Liberate,” Douglas Schuler, Online Deliberation: Design, Research, and Practice, University of Chicago Press, 2009.

[117] “Semi-structured messages are surprisingly useful for computer-supported coordination,” ACM Transactions on Office Information Systems, Thomas Malone, et al., 1987.

[118] Understanding Computers and Cognition, Terry Winograd and Rodrigo Flores, Addison-Wesley, 1987.

[119] How to Do Things with Words, J. L. Austin, Harvard University Press, 1962.

[120] “Deliberation and Community Networks: A Strong Link Waiting to be Forged,” Fiorella De Cindio and Douglas Schuler, Communities and Action: Prato CIRN Conference, 2007.

[121] “A Two-room E-Deliberation Environment,” Fiorella De Cindio, et al., Directions and Implications of Advanced Computing: Conference on Online Deliberation. San Francisco: Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility, 2008.

[122] Robert’s Rules of Order, Newly Revised, Henry Robert, Perseus Books, 1990.

[123] “‘Tools for Participation’ as a Citizen-Led Grand Challenge,” Douglas Schuler, Directions and Implications of Advanced Computing: Conference on Online Deliberation, San Francisco: Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility, 2008.

Get Open Government now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.