Chapter 19. Case Study: FollowTheMoney.org

Transparency surrounding state-level campaign-donor information has improved greatly in the past decade, largely due to significant improvements to the Internet and the demand it has created for access to all types of government information. But for all the good that technology has made possible, the age-old lack of political will has stymied efforts to significantly advance transparency in many states.

Accessing Political Donor Data Fraught with Problems

Government at all levels has yet to realize the efficiencies and cost benefits that transparency has to offer—whether political donor data, lobbyist information, contracts and vendors, or legislation. Agency directors must guide reluctant lawmakers to the table with concrete examples of reduced duplication, more competitive contracting, and due diligence where candidates and political favors are concerned. The potential is staggering, for taxpayers and voters, and for our democracy in general. But we have a long way to go.

The good news about political disclosure is that ethics commissions or campaign finance disclosure agencies in all 50 states have a web presence, which shows they understand that the public now expects political donor information to be available online.

The bad news is that agencies in 35 states think “electronic data” means online PDF images of reports for some, not necessarily all, of the candidates. For four other states, the online databases created by disclosure agencies are of such poor quality that the data itself must be reentered from paper reports originally filed by committees.

One dramatic shift toward transparency took place when Wyoming passed legislation in 2008 requiring full electronic filing and disclosure beginning in 2010—a far departure from the infrequent and paper-only filings required up through the 2008 elections that had for years earned that state failing grades in national state-of-disclosure reports.

The National Institute on Money in State Politics’ Role in the Fight for Greater Transparency

The National Institute on Money in State Politics is the only nonpartisan, nonprofit organization revealing the influence of campaign money on state-level elections and public policy in all 50 states.

In 2009, the Institute itself launched three significant projects:

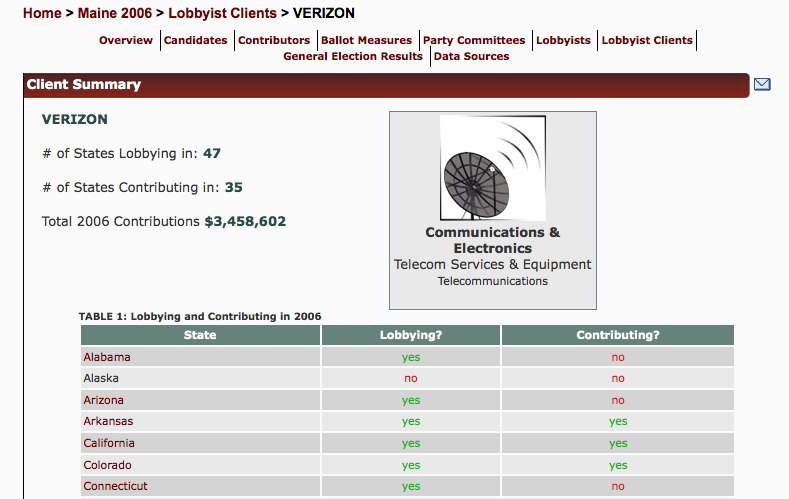

The Lobbyist Link mashup of lobbyists registered in 2006 and 2007 in the 50 states (adding 2008 and 2009 now), their clients, and the donations made by both (see Figure 19-1). So, in a couple of clicks on a map, users can see a list of lobbyists active in a state, their clients, and, most important, to whom those clients gave campaign donations. Search for, say, Verizon and see that in 2006 the company hired lobbyists in 47 states and gave more than $3.4 million in donations in 35 states.

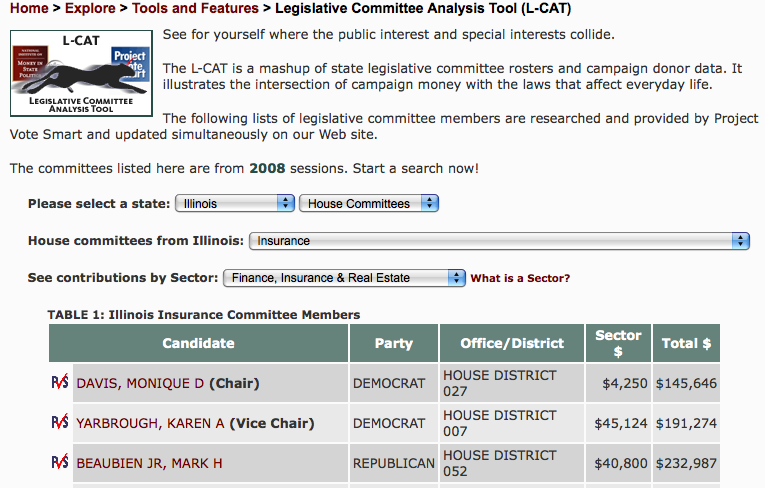

The Legislative Committee Analysis Tool uses application programming interface (API) data calls to Project Vote Smart’s database so that political donors can be grouped by legislative committee assignments—where the most important legislative activities occur (see Figure 19-2). By selecting a state and a House, Senate, or Joint Committee, a user can see a list of committee members and how much they raised in their campaigns. The true power of this tool comes with the next step, when the user filters by the economic interest of donors to committee members. For example, selecting Illinois and its House Insurance Committee shows the 23 members, their parties and districts, and totals raised. Then, filtering by donors from the finance, insurance, and real estate industries, the user sees how much each member received from those donors, as well as a list of those donors, how many committee members they gave to, and how much they gave in total. This way, users can see which donors with an economic interest targeted their donations to members of committees with specific interests. The PVS icon next to the member’s name takes the user to biographical information compiled by Project Vote Smart for each member.

Just one year earlier, the Institute and Project Vote Smart first used APIs to combine candidate biographies and voting information with donor lists. More than 300 individuals and organizations have now signed up for the Institute’s APIs, which can automatically feed and update donor information to outside websites. Project Vote Smart and the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP; http://www.opensecrets.org/) also now make their data available via APIs. Sunlight Foundation is advancing transparency via grant-making and innovative projects.

Additional data visualization tools at FollowTheMoney.org let users see when a company’s or industry’s donations were made in a two-year timeline that corresponds to an election cycle with the Timeline tool, see a specific industry’s donation totals over several election cycles with the Industry Influence tool, or look at how competitive legislative races are in their state with the (m)c50 tool.

Bolstering the Spirit of Public Disclosure Laws

Any researcher or reporter knows that if this type of information isn’t in a complete, accurate, searchable database, the relationships between politicians and donors can’t be revealed in a meaningful way. So, while lawmakers and disclosure agencies are complying with political donor reporting requirements by making paper or PDF copies available to the public, they are ignoring the spirit of the public disclosure laws.

The Institute compiles state-level donor information from all 50 states, filling the huge void between important public information and the public’s ability to access that information. To do so, it has to build a database of all 16,000-plus state candidates and committees that register each two-year election cycle. These candidates file upward of 100,000 campaign finance reports, which result in a database of more than 3 million records that total more than $3 billion. Most of this donor information is reported in the couple of months preceding and just after the elections, but untimely filings and amendments complicate the work.

Like other nonprofits involved in government oversight and transparency, the Institute strives to show agency officials and staff members that people want the public information they compile, and that this lack of political will is a barrier whose days are numbered. Most agency staff members are eager to see the fruits of their efforts elevated to twenty-first-century standards.

In 2008, the public was offered an excellent example of what is possible if elected officials and disclosure staff members work together. The Illinois State Comptroller’s office launched its Open Book mashup of state contracts and political donors. Thus, for the first time, Illinois voters had information that lets them ask whether political donations result in favoritism in state contracting. In contrast, more than 20 states offer search functions for vendor or contract information on their websites, but only a handful offer downloadable databases. As of May 2009, Alaska, Kansas, Missouri, and Texas had launched sites that show detailed fiscal information, such as revenue, expenditure, program, and vendor payments.

State-Level Transparency Faces Serious Challenges

The fledgling transparency movement is quickly moving from childhood to adolescence. The sobering developments around the economy, economic stimulus spending, and corresponding accountability efforts have elevated the public’s desire for more digital information and spurred organizations to develop evidence-based visual analyses. As the federal government ramps up Recovery.gov, designed to track stimulus spending, the transparency movement will mature further. But the infrastructure of democracy will increase in efficiency only if and when the collective political will catches up with the potential of technology.

Defining “a lack of political will” is difficult. But it is easy to recognize when you experience it. Perhaps the best example of a lack of political will for transparency is at the federal level, where the U.S. Senate refuses to move its campaign finance disclosure to an electronic format—despite the millions spent on sophisticated campaigns. At the state level, it manifests in different and often subtler ways. Missouri disclosure officials insist that the jumbled, undelimited electronic data they provide in a single field is the best they can offer. That strains credulity. When, years ago, Utah’s new campaign finance website went offline for the duration of the legislative session, that, too, strained credulity.

More commonly, disclosure agencies and staff members get caught in the “two bosses” trap, where they must pay attention to the desires of elected lawmakers who control the agency’s budget, and the public, which is genuinely hungry for information about political donors, lobbyists, and their relationships to legislation and contracts. Montana is a good example of this. During the tenure of at least four political practices commissioners, the campaign disclosure agency has hired vendors to help implement an online filing and disclosure system, purchased several software packages, and input donor data and campaign expenditures in different formats and programs. Now, more than seven years later, electronic disclosure in Montana has improved to include PDF images of contribution and expenditure reports online, but still no database.

South Carolina has long been judged one of the most fragmented and unavailable states for public disclosure of campaign finances. Statewide candidates and political party committees filed reports with the State Ethics Commission, Senate candidates with the Senate Ethics Committee, and House candidates with the House Ethics Committee. None of this information was available online for viewing. It was available to the public only after the Institute obtained paper copies of filed reports and manually input the data to its online database. In 2003, South Carolina legislators passed legislation requiring online filing of campaign finance reports. Sounds good, right? Nothing changed—due to a failure to include any funding to develop an electronic filing system. In 2006, statewide candidates were supposed to begin filing online reports; the first reports for these candidates were not filed until January 15, 2008, even though none of those candidates were up for office again until 2010. In April 2008, some Senate and House candidates began filing their reports online. However, large campaign war chests raised during 2007 for these elections are not disclosed on the state website. It remains to be seen how the online filing actually works during the 2010 election cycle, but the current data is not easily searchable and it can be downloaded in only bits and pieces from individual pages of each report. While this would be a marked improvement over the previous processes, it underscores the type of foot-dragging encountered on the long and tortuous trail toward real transparency in South Carolina state politics.

Connecticut is another example. It has had an electronic reporting system for campaign contributions for a few years. However, at first the online data was not downloadable and the private contractor operating this database quoted the Institute a price of $10,000 for each download of data. Therefore, Institute staff members had to print the reports, then input, audit, standardize, and upload this data to provide free public access. With a change in administrations in 2006, the state began implementing a new electronic filing system. However, current election-cycle reports are not searchable or downloadable during the cycle; one is only able to view individual reports in PDF format. To provide a transparent, searchable database, the Institute still must print individual reports, then input, audit, standardize, and upload the data.

Arkansas makes available online images of candidate and political party committee reports. But when it comes to reporting donors to ballot measures, the reports are sporadically posted for select ballot measure committees. In fact, the online listing of the registered committees—needed to expedite requests to the state for reports—is incomplete, so the public has no way of knowing if a committee was formed officially or if it filed reports.

Many states that do offer electronic filing, and databases for download or purchase, do not provide complete information in their databases. For example, Texas, New Jersey, Colorado, Iowa, and California do not require all candidates to file electronically, so the Institute must manually enter paper reports into a searchable database. Other states, such as Indiana, Kentucky, Colorado, and Michigan, do not include data for small contributions reported as lump sums, loans, and returned contributions in their electronic data—again requiring manually input data to complete the stories.

While Missouri has an online searchable database, the contributor data provided to anyone ordering a copy of the data is sent all in one field. Parsing the contributor data into separate fields to make the data useful is a more egregious task than reentering all the data from scratch from printed copies of the reports.

Finally, as the public begins to look at and download data from disclosure agencies, they must keep a critical eye out for clues about the completeness of the data. In Utah, the Institute has requested electronic data time and again, only to find on closer inspection that large chunks of the database are missing. Successive requests have resulted in no satisfaction, so the Institute simply prints off the paper reports and enters the data manually.

California offers yet a different example of issues facing public disclosure in the states. While it probably has the most complete and easily searchable database of campaign contributions at the state level, the system is in peril of crashing due to its aging information and hardware architecture. When coupled with ongoing budget shortfalls that preclude spending funds to revamp this massive database, one major glitch could cause the whole system to become ineffective.

In an Ideal World: Recommendations for Open Data

While it’s easy to point out the flaws with disclosure of political and other types of public information at the state level, offering concrete, implementable solutions is more difficult, given the nature of the information being requested and the potential political pitfalls that cause elected politicians to balk at approving solutions.

In the perfect world envisioned by staff members at the National Institute on Money in State Politics:

Disclosure, enforcement, and ethics agencies would be independent of elected offices and, as much as possible, of elected officials themselves. Political donor and lobbyist disclosure in many states is housed in the office of the governor, secretary of state, or lieutenant governor, who often don’t see that the advantages of robust disclosure far outweigh any political liabilities.

Budgets for independent disclosure agencies would be set at realistic levels and protected from the whims of political retribution. For instance, ethics commissions in both Alaska and Washington have seen their budgets cut as a result of enforcement actions against politicians, even when further review found those actions to be warranted. Staff members need to be free to perform professionally without fear of retribution, and have the technology and equipment to do their jobs properly.

Electronic filing of candidate personal disclosure, campaign donor, lobbyist, and client as well as legislative committee and legislation information would be required of all who use computers. Staff members would input all information or would offer computer access for those who don’t have computers. The data input by state staff members would be audited for accuracy. (Exemptions from donor filing requirements are reasonable for candidates who raise less than, say, $2,500.)

A unique ID would be assigned to any candidate or lobbyist and would follow that person through his career, providing easy access to personal disclosure and donor information, committee assignment, legislation, and voting records.

Databases and information filed by candidates and lobbyists would have to adhere to standard database protocols, including delimitation of fields, and be downloadable in Excel and basic text formats.

Donor and lobbyist information would include full addresses, and occupation and employer information, to aid in accurate identification of individuals and the analysis of relationships.

RSS and API methods would be established so that groups as well as individuals would be able to easily track information and the activities of their elected officials.

On the larger stage, this level of transparency would enable deeper integration with state contracting/vendor information, thus allowing the public the opportunity to judge whether policy and spending decisions are based on political influence and friends of politicians, or on the weight of their value.

Conclusion

Data wonks understand that if you put all the candidate information, the political donor information, the lobbyist information, and legislation, fiscal impact, contract, and vendor information into one database and perform basic businesslike analytics on that data, you would discover tremendous duplication of services at different costs, low-value program cost-benefit relationships, and even the appearance of influence peddling, which could be used to establish new due diligence protocols for policymakers and politicians. The public is quickly learning how to do such analyses themselves, through new social networks developed on the Internet.

Our democracy, already a powerful and vibrant method of organizing activities and resources for the common good, can become even more effective by applying simple cost-benefit measures at the policy implementation level, and placing a broad understanding of the players and their motivations at the forefront of the debates.

If we let it, the Internet will ensure that many eyes are on the lookout for bugs in the policy/fiscal soup.

Institute Deputy Director of Operations Linda King contributed to this chapter.

About the Author

Edwin Bender is executive director of the National Institute on Money in State Politics. Edwin was named executive director in August 2003 after serving as the Institute’s research director since its creation in 1999. In that role, he led the research functions of the Institute, directing both the development of campaign finance databases and analyses of those databases. A former journalist, Edwin also worked for seven years as research director for the Money in Western Politics Project of the Western States Center. While there, he helped develop many techniques for researching state campaign-finance data.

Get Open Government now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.