Chapter 4. Making the ROI Case

One of the first things that is asked of any new project in a modern IT department is that a cost benefit analysis be created to determine if the investment of time and resources makes sense. This takes many forms, but at many companies the idea of return on investment, or ROI, is king.

Management’s goal in asking for an ROI analysis is simple: explain why an open source project (or any other project) is going to help the organization succeed by increasing revenue or saving money. Technologists frequently are annoyed by the request to analyze ROI, for several reasons:

It is hard to create a defensible approach. The results of almost any ROI analysis can be changed massively, by adjusting assumptions.

Intangible benefits, such as flexibility or creating a simpler architecture, are frequently undervalued or are not included.

Besides reducing technical costs, technologists have difficulty making reasonable estimates about how the new technology will increase revenue.

Despite these difficulties, ROI is here to stay, and almost every IT department that intends to use open source must figure out a way to determine the ROI of open source. Reasonable managers will not give open source a pass on faith. This chapter will provide an informal guide to analyzing the ROI of using open source.

ROI Fashions

The need for ROI comes and goes. In boom times, when IT is being asked to support more business activity as quickly as possible, ROI is no longer king. It gets deposed and becomes a proletariat. However, when the return is out there for the taking, if you can execute a business strategy quickly, the investment in IT to speed execution is not scrutinized nearly as closely. During times such as these the CEO or VP of sales might be most influential in promoting IT investment. But when times are sour, the CFO emerges as the most important gatekeeper—and CFOs love ROI analysis.

Most managers know that ROI is difficult to create. When something makes sense but is hard or impossible to quantify, managers are inventive when it comes to finding ways to justify investments without ROI. One common approach is to call something a strategic investment, meaning the investment makes sense and will improve the company’s position despite the fact that a hard dollar analysis is nebulous. Billions of dollars are spent on strategic projects.

Technology vendors are very hip to the value of an authoritative ROI study. Most software vendor web sites contain and prominently feature ROI studies for specific uses of the software or for specific industries. Microsoft, for example, has commissioned several ROI studies about Linux. They all show—surprise, surprise—that Linux is more expensive, using assumptions that match few real-world situations. Some of the commercial companies promoting the ROI of Linux have also created studies showing that Linux costs less than the alternatives, but they use assumptions that apply to only a few companies.

For most uses of open source, there is no vendor preparing an ROI study. Even a specious ROI study can be adjusted with assumptions that match more closely the conditions at your company. Getting ROI correct is always a “do it yourself” proposition. With that in mind, let’s discuss how you can determine the ROI of an open source project.

What Is ROI for Open Source?

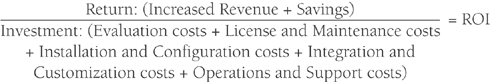

At a high level, calculating ROI for open source is pretty much the same as for commercial software. The equation looks something like this:

Of course, for such an equation to make sense we must understand many things:

What is the time horizon for the analysis? How long will we get to count revenue or savings against this investment? One year? Two years?

Is it possible to compare alternatives? Should we choose the fastest time to payback or the largest savings over the long term?

What are the interest rate assumptions? What is the hurdle rate--that is, the minimum return—for any investment for the company?

What costs will be included and what will be assumed to be born as infrastructure costs? ROI analyses frequently don’t include the extra costs of electric power or bandwidth. Sometimes ROI analysis includes hosting, and other times it doesn’t.

Should reduced costs in the future, or costs than can be avoided, be included? How can such costs be reasonably estimated?

Are the same costs between the alternatives being compared? Has the analysis for one product assumed away costs, or underestimated them? What costs are vendors concealing or disregarding?

The answers to these questions can vary widely, and they illustrate why ROI calculation is much more an art than a science. The vendor ROI studies sponsored by Microsoft carefully tune the assumptions against Linux by comparing mainframe-like machines from IBM running Linux with large PCs running Windows. Microsoft is not unique in its manipulation of assumptions. Almost all vendors do this to some extent. No defensible set of assumptions applies to all situations.

Other questions are of great significance to how an ROI analysis is constructed. Is there a minimum payback period for all IT investments? How much will it cost the company, and how much can it earn from alternative investments? If interest rates are high or a company has profitable businesses that need money to grow, the bar for investing in IT can become high indeed.

The last point in the list about using equivalent costs is the one that makes comparing commercial and open source software most difficult. The costs of open source have a different shape than the costs of commercial software.

How Open Source Costs Differ from Commercial Software Costs

On the return side of the equation there is not much difference between open source and commercial software. Revenue is revenue, and if a computer system helps support it, that’s great. It is possible for two different alternatives to meet the goals of creating revenue in different ways, but we can draw no generality about open source always being better to support the creation of revenue. For savings the situation is much the same. Once the estimated savings are determined for each alternative, there is not much to do but compare.

Calculating savings is another black art. It is easiest to do when known costs are eliminated or are replaced with a new set of lower costs. But an honest analysis of savings would have to quantify savings due to differences in reliability, downtime, maintenance procedures, and so on. Many of these issues are hard to quantify in a defensible manner.

The nature of the costs of open source and commercial software is truly different, however.

Evaluation Costs

The costs of evaluating open source can be considered part of the ROI analysis, so it might not be included in the ROI equation, but it does take time, more time generally than for commercial software. At some level it should be included in management’s thinking about the costs and benefits of using open source.

During the sales process for commercial software, vendors are eager to educate potential buyers about why their software is valuable. To buy software, an IT department must be convinced that:

Their organization has a need for some software in a certain space.

The vendor’s offering is the best choice.

Right now is the time to buy the product.

Vendors spend a lot of money on whitepapers, marketing materials, conferences, and other content to communicate all three of these points. Many IT executives use vendor materials heavily to “get smart” about a space.

For open source, few such materials exist. Open source projects rarely come with whitepapers explaining why you need the software. Open source communities just assume that you need it; that’s why you are visiting the site. The product description of open source materials often happens at a relatively detailed level. (“This is a content management system. Here is the API documentation. See the code samples for further clarification.”) And open source projects really don’t care if you have a need now, or sometime in the future.

So, to really understand what an open source project can do, an IT department must install it and play with it, and this takes time and different sorts of resources. A typical commercial software evaluation might take place with the sales staff or with IT managers who screen the products, bringing in the architects or developers later only if the product looks promising. For an open source evaluation, the developers and architects should probably take the lead. An architect or developer’s time might be worth more in some organizations than a manager’s time. This must be planned for. The amount of time it takes to install a product is based on the IT organization’s skills. Expert and advanced users can install and get most open source software operating in two or three hours. A user at a strong, intermediate skill level should be able to have most open source software running within a day.

In addition to the cost of creating a trial installation, the IT staff must learn enough about the software to play around with it and understand its functionality to determine if it can meet the company’s requirements. While this is another activity that consumes technical resources, it also removes a significant amount of risk from the process. By using an open source product to create prototypes, the IT staff can compare the actual functionality with the requirements, and can validate the requirements by having users interact with the prototypes.

Arranging a similar installation of commercial software might require any or all of the following:

Negotiation of a trial license that might have a time limit

Payment of service fees to support the trial installation

Training

Trial licenses for additional related software

Vendors might or might not be open to a trial installation. After all, the investment in all the educational and marketing materials is supposed to make the value and functionality of the software clear.

In the end, the evaluation of open source can involve more technical resources than an IT department is accustomed to, but can also result in a deeper understanding of both the software and the requirements. With commercial software, management might take the leading role, and with open source the technologist might be the primary analyst. In either case, care must be taken to ensure that one side doesn’t dominate the evaluation and create a disconnect between the business and technology requirements.

License and Maintenance Costs

An extremely naïve view of open source, one frequently promoted by technologists who are eager to use open source, focuses solely on the fact that there are no license or maintenance fees to pay. License and maintenance fees for commercial products can range from as low as a few percentage points to as much as 20 points or more of the total solution. But the savings in license fees is no guarantee that open source is the right choice.

First of all—and this might come as a shock—some open source does come with what amounts to licensing fees. Companies are frequently happy to pay subscription fees for Linux distributions from Red Hat or SuSE to get a coherent collection of software, packaged consistently, with a nice installation program and a steady stream of updates. Other projects such as JBoss charge licensing fees for documentation, and Resin actually requires licensing fees for commercial use, even though it seems like open source. Open source is no guarantee of zero licensing costs.

While there is no maintenance fee for open source—upgrades are free—you often have to spend more time with an open source project to figure out what is in the upgrade. Perhaps the best news is that upgrades are never forced on you, the way they so often are with commercial software. An IT department can move from one version to the next whenever the time is right for the company, not when the vendor can no longer afford to support maintenance of older versions.

Increasingly, however, it is possible to find traditional support and maintenance for open source software. Several start-ups offer support for various open source projects and useful combinations of projects. One of the reasons companies like using commercial software is that it means an organization exists that can be held accountable for the software. The new wave of start-ups is responding to this need and is providing “one throat to choke” in exchange for a fee.

Installation and Configuration Costs

Installation and configuration of open source can be time consuming, especially for beginner or intermediate organizations that are not deeply skilled in the use of open source tools. To install an open source program and then get it running can require a fair bit of fiddling, especially with more immature products that have not been used much outside their native environment. Commercial software generally comes with some sort of install wizard that guides the user through installation and basic configuration. While more and more open source projects are showing this degree of professionalism, the use of such wizards is still not widespread.

Configuring the software, the process of changing all the settings so that the software behaves as desired, can also take longer for open source, as the mechanisms of configuration are discovered more through trial and error or reading code rather than through some comprehensive documentation. At a fine-grained level, especially for large programs, configuring a commercial software program can be a black art as well. Undocumented settings are routine in the commercial world and frequently are discovered by IT departments only after lengthy support calls or expensive engagements for services.

The real factor in determining whether installation and configuration will require a significant time commitment is an organization’s skill level in using open source development tools, system administration, and operations. In general, beginners and those at the intermediate skill level will spend more time on installation and configuration than will more highly skilled IT departments.

Integration and Customization Costs

Careful assessment of integration and customization costs in many ways is the key to avoiding an open source nightmare. Unlike commercial products, open source projects are not usually created with the modern IT infrastructure environment in mind. Integration with single sign-on or support for monitoring protocols such as SNMP might not exist. Support for databases might be narrow and limited to a few choices or to one database. Support for standards might be lacking.

Most of the time, the same problems exist in emerging commercial software that is early in its life cycle. But as the commercial program is installed in more and more IT environments, smart vendors seek to productize the most common integrations so that the same work is not required again with each new client.

Some companies have unique integration problems that will always have to be solved through custom coding, regardless of whether open source or commercial software is used. The question is how easy that integration will be to create. And that can be determined only on a case-by-case basis. It is possible to argue that open source integration can be less expensive, because access to source code means you can always do the work yourself.

The need for customization arises when the open source project must be extended to meet the requirements at hand. Here, open source becomes a gray area between a buy versus build decision. Open source represents the decision not to buy, but to build as little as possible. And don’t forget: the skills to customize an open source product must be created inside an organization or be obtained through consulting services.

With an open source program it is far more likely that an IT department will have to solve an integration or customization problem on its own. Then the question once again boils down to having the needed skills or renting them. If a web content management system, for example, doesn’t support a single sign-on mechanism, someone will have to write the code to add that support.

Once such code is written, it can be either donated to the community and maintained as part of the project’s source code, or kept as a proprietary modification that must be maintained and updated with each new release. In general, beginner and intermediate-level users require some sort of consulting help in creating such integrations, and advanced and expert users can do it on their own if they choose.

It’s hard to generalize about whether this is a strength or a weakness of open source. It is clearly a weakness to the extent that more integration work is probably needed for the average open source project than for the average commercial project, which might have productized some of the integration. On the other hand, the answer is never “no” when it comes to integrating open source. Almost everyone who has used commercial software to support a business has come across a need that requires changing the software in a special way to optimize support. Perhaps a company has a custom-built operational monitoring system or a clever use of a data warehouse or the desire to integrate tightly with a desktop application. Commercial vendors frequently won’t make such modifications for an IT department, and they won’t provide the source so that an IT department can do it for themselves. Anything can be done with open source, so the barrier to creating the optimal system for supporting a business process is often lower. The higher the skill level, the lower the bar will be.

Operations and Support Costs

On the surface, operations and support costs do not look that different between open source and commercial software. Once software is installed, configured, and integrated, it is just software, whether it is open source or not. Skill levels play a large role in determining the time required to support both commercial and open source software. But when it comes to configuring a professional environment, open source leaps way ahead.

Commercial software vendors might require licensing fees for any of the following situations:

Creating a development environment on each developer’s workstation

Creating a test environment or a staging environment

Adding servers for scalability

Adding servers for disaster recovery or for a hot backup site

For a vendor, all of this makes perfect sense. The more an IT department uses a product, the more value it gets from that product and the more it should pay for the product. But as a practical matter these ancillary licensing fees increase the cost and get in the way of optimizing the performance and stability of an environment. It can be a nasty surprise to find out that an expensive license stands in the way of scaling an application or creating the right disaster recovery site.

The Cost of Narrowness

Looking back on the difference between the costs of open source and commercial software, a theme emerges. In open source, the burden is on the IT department to develop or find the skills to evaluate, install, configure, operate, and support the software. If this burden is accepted, anything is possible.

For commercial software, these burdens can take less time and cost more money, but the range of possibilities is narrower and is confined to the common needs of the marketplace the vendor should support. The cost of this narrowness is the defining issue. How can you measure the cost of commercial software’s narrowness and rigidity? If you never run into a barrier, the cost is zero. If you have a great need for a certain feature, it can be huge.

The same question must be asked of the functionality of the open source project. If there is a large gap between the needs of an IT department and the use cases that are the focus of the open source project, that gap might need to be filled. Doing so might require a significant time investment and a certain level of skill.

If you have a clear understanding of how a piece of software is going to be used, and you are confident that it is stable and unlikely to change or need optimization, perhaps the bias should be in favor of commercial software. On the other hand, if you need software that is optimized and tuned to meet perfectly the needs of a crucial business process, perhaps open source is the right choice. We will return to this analysis in detail in Chapter 5.

Making Your Own ROI Model

The bottom line is that you must do ROI analysis for yourself, whether using commercial or open source solutions. And while the true costs are rarely quantifiable or authoritative, doing the analysis for an open source project is vital, because it can expose the true costs and risks, and help an IT department prepare for them.

Now that all of the ideas about costs are swirling before you, let’s take a close look at how you can create an ROI model to express all of these factors. There are, of course, many ways to go about creating such a model. This section will walk through a flexible approach that should apply to most situations faced by IT departments.

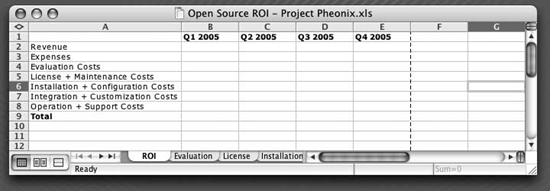

Creating the ROI Analysis Spreadsheet

A reasonable way to start an ROI analysis is to start with a spreadsheet that represents the equation mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. Let’s assume a three-year analysis. The first page of the spreadsheet will have one row each for revenue and expenses, and one row for category of cost. At the bottom is a row that totals up the column according to the ROI formula (see Figure 4-1).

Each column represents a time period; let’s assume one quarter.

After the first page of the worksheet is one worksheet page dedicated to each of the revenue and expense categories. The columns of these worksheets are the quarterly periods, just like on the summary sheet. The rows are the specified line items that make up the cost estimates. All the costs are estimated in dollars. If hourly time estimates must be created, they can be done on the rows of the worksheets or on other worksheets. The rest of this chapter will provide suggestions for what might make up the rows of each worksheet.

Creating the Estimates

Consistency in approach is perhaps more important than accuracy in such an analysis, for two reasons. First, accuracy is hard to come by. For some data, it will be possible to get numbers to back up estimates. For example, if an application can be retired and replaced with open source, maintenance no longer needs to be paid and

the resulting savings will be clear. But how much time will be spent installing, evaluating, integrating, maintaining, and supporting the open source solution? These numbers will be hard to come by, especially if an IT department does not have a lot of experience with open source.

Second, if some sort of consistent approach is used, the analysis can be adjusted at the detail or summary level, with some hope that the model will not break down. In this way, it becomes clear to everyone reading the model that certain estimates are based on guesses, all of which are constructed in the same manner. The analysis should explicitly state how the guesses were constructed and why they are justified. For example, an IT department assumes that there will be four production servers and that configuring the first one will take 20 hours. The department can then replicate that configuration to three identical servers in two hours each. It will be possible to track this configuration time and then plug the real data into the model to see how it has changed. Another example: if it turns out that the configuration was underestimated by about 30% in the first 2 of 10 configurations, a new model can be created by reducing the 8 configuration estimates by 30%, if all of them were constructed in the same way.

So, in general, the more granular and measurable the analysis is, the better a planning tool it will be. As an IT department becomes more experienced with open source, its ability to estimate specific costs will improve.

Elements of Evaluation Costs

As we noted earlier in this chapter, evaluation costs for open source are generally higher and require different resources than for commercial software. An engineer, for example, will spend a significant amount of time researching and implementing an open source program. The following is a list of jobs an engineer will spend time performing while evaluating an open source project (these could also be included as line items in a cost estimate):

Searching for open source

Creating a test environment

Installing and configuring software

Writing test programs

Researching questions and problems

Researching integration techniques and costs

Networking with open source community members and looking for answers to questions

Elements of Installation and Configuration Costs

Installation and configuration costs are the costs of figuring out how to install the software in your test and production environment, and make it work the way you want it to work, by using the settings and parameters that are intended for that purpose. Elements of installation and configuration costs include:

Engineer time spent learning how to install the software in a development environment

Engineer time spent learning how to install the software in a test environment

Engineer time spent learning how to install the software in a production environment

Engineer time spent doing basic performance testing

Engineer time spent developing backup scripts

Engineer time spent learning how to operate the software

Engineer time spent learning how to monitor the software

Engineer time spent integrating the software into production monitoring and alerting systems

Training time for developers

Training time for top operations staff

Elements of Integration and Customization Costs

Integration and customization costs include the planning, design, and development required to integrate the software into an IT department, and to extend the software’s functionality to meet the needs at hand. Elements of integration and customization costs include:

Engineer time spent gathering requirements for integration and customization

Engineer time spent reading source code, documentation, and bulletin boards to understand the workings of the software

Engineer time spent designing the integration and customization

Engineer time spent coding the integration and customization

Engineer time spent testing the integration and customization

Fees for any consultants brought in to help the process

Elements of Operations and Support Costs

Operations and support costs are the costs incurred to run the open source project in production. Many of these costs are similar to those incurred for commercial software. Elements of operations and support costs include:

Hardware costs

Rack space

Electric power

Network bandwidth

Operational monitoring

Backups

Skills Versus Money

If this list seems long, remember that most of the elements represent time spent by an engineer to learn how best to use the software. In other words, the investment in open source is also an investment in increasing an IT department’s skill level.

The commercial analog to most of these costs represents renting expertise that does not leave an IT department smarter. Sometimes money is more important than the time it takes to solve a problem. But in general, it is hard to argue that creating a more skilled organization is anything but a net positive for an IT department.

As an IT department’s skills grow, more open source will become usable. The question then becomes which open source projects will provide the most benefit. In the next chapter, we turn to the issue of how to focus efforts according to a coherent strategy.

Get Open Source for the Enterprise now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.