Chapter 4. URLs

Now that you’ve seen how LWP models HTTP requests and responses, let’s study the facilities it provides for working with URLs. A URL tells you how to get to something: “use HTTP with this host and request this,” “connect via FTP to this host and retrieve this file,” or “send email to this address.”

The great variety inherent in URLs is both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, you can stretch the URL syntax to address almost any type of network resource. However, this very flexibility means attempts to parse arbitrary URLs with regular expressions rapidly run into a quagmire of special cases.

The LWP suite of modules provides the URI class to manage URLs. This chapter describes how to create objects that represent URLs, extract information from those objects, and convert between absolute and relative URLs. This last task is particularly useful for link checkers and spiders, which take partial URLs from HTML links and turn those into absolute URLs to request.

Parsing URLs

Rather than attempt to pull apart URLs with regular expressions, which is difficult to do in a way that works with all the many types of URLs, you should use the URI class. When you create an object representing a URL, it has attributes for each part of a URL (scheme, username, hostname, port, etc.). Make method calls to get and set these attributes.

Example 4-1 creates a URI object representing a complex URL, then calls methods to discover the various components of the URL.

use URI;

my $url = URI->new('http://user:pass@example.int:4345/hello.php?user=12');

print "Scheme: ", $url->scheme( ), "\n";

print "Userinfo: ", $url->userinfo( ), "\n";

print "Hostname: ", $url->host( ), "\n";

print "Port: ", $url->port( ), "\n";

print "Path: ", $url->path( ), "\n";

print "Query: ", $url->query( ), "\n";Example 4-1 prints:

Scheme: http Userinfo: user:pass Hostname: example.int Port: 4345 Path: /hello.php Query: user=12

Besides reading the parts of a URL, methods such as host( ) can

also alter the parts of a URL, using the familiar convention that

$object->method reads an

attribute’s value and $object->method(

newvalue )

alters an attribute:

use URI;

my $uri = URI->new("http://www.perl.com/I/like/pie.html");

$uri->host('testing.perl.com');

print $uri,"\n";

http://testing.perl.com/I/like/pie.htmlNow let’s look at the methods in more depth.

Constructors

An object of the URI class represents a URL. (Actually, a URI object can also

represent a kind of URL-like string called a URN, but you’re unlikely

to run into one of those any time soon.) To create a URI object from a

string containing a URL, use the new(

) constructor:

$url = URI->new(url[,scheme]);

If url is a relative URL (a fragment such as staff/alicia.html),

scheme determines the scheme you plan for

this URL to have (http, ftp, etc.). But in most cases, you call

URI->new only when you know you

won’t have a relative URL; for relative URLs or URLs that just

might be relative, use the URI->new_abs method, discussed below.

The URI module strips out quotes, angle brackets, and whitespace from the new URL. So these statements all create identical URI objects:

$url = URI->new('<http://www.oreilly.com/>');

$url = URI->new('"http://www.oreilly.com/"');

$url = URI->new(' http://www.oreilly.com/');

$url = URI->new('http://www.oreilly.com/ ');The URI class automatically escapes any characters that the URL standard (RFC 2396) says can’t appear in a URL. So these two are equivalent:

$url = URI->new('http://www.oreilly.com/bad page');

$url = URI->new('http://www.oreilly.com/bad%20page');If you already have a URI object, the clone( ) method

will produce another URI object with identical

attributes:

$copy = $url->clone( );

Example 4-2 clones a URI object and changes an attribute.

use URI;

my $url = URI->new('http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/');

$dup = $url->clone( );

$url->path('/weblogs');

print "Changed path: ", $url->path( ), "\n";

print "Original path: ", $dup->path( ), "\n";When run, Example 4-2 prints:

Changed path: /weblogs Original path: /catalog/

Output

Treat a URI object as a string and you’ll get the URL:

$url = URI->new('http://www.example.int');

$url->path('/search.cgi');

print "The URL is now: $url\n";

The URL is now: http://www.example.int/search.cgiYou might find it useful to normalize the URL before printing it:

$url->canonical( );

Exactly what this does depends on the specific type of URL, but

it typically converts the hostname to lowercase, removes the port if

it’s the default port (for example,

http://www.eXample.int:80 becomes

http://www.example.int), makes escape sequences

uppercase (e.g., %2e becomes

%2E), and unescapes characters that

don’t need to be escaped (e.g., %41

becomes A). In Chapter 12, we’ll walk through a

program that harvests data but avoids harvesting the same URL more

than once. It keeps track of the URLs it’s visited in a hash called

%seen_url_before; if there’s an

entry for a given URL, it’s been harvested. The trick is to call canonical on all

URLs before entering them into that hash and before checking whether

one exists in that hash. If not for calling canonical, you might have visited

http://www.example.int:80 in the past, and might

be planning to visit http://www.EXample.int, and

you would see no duplication there. But when you call canonical on both, they both become

http://www.example.int, so you can tell you’d be

harvesting the same URL twice. If you think such duplication problems

might arise in your programs, when in doubt, call canonical right when you construct the URL,

like so:

$url = URI->new('http://www.example.int')->canonical;Comparison

To compare two URLs, use the eq( )

method:

if ($url_one->eq(url_two)) { ... }For example:

use URI;

my $url_one = URI->new('http://www.example.int');

my $url_two = URI->new('http://www.example.int/search.cgi');

$url_one->path('/search.cgi');

if ($url_one->eq($url_two)) {

print "The two URLs are equal.\n";

}

The two URLs are equal.Two URLs are equal if they are represented by the same string

when normalized. The eq( ) method

is faster than the eq string

operator:

if ($url_one eq $url_two) { ... } # inefficient!To see if two values refer not just to the same URL, but to the

same URI object, use the ==

operator:

if ($url_one == $url_two) { ... }For example:

use URI;

my $url = URI->new('http://www.example.int');

$that_one = $url;

if ($that_one == $url) {

print "Same object.\n";

}

Same object.Components of a URL

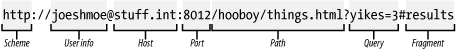

A generic URL looks like Figure 4-1.

The URI class provides methods to access each component. Some components are

available only on some schemes (for example, mailto: URLs do not support the

userinfo,

server, or port

components).

In addition to the obvious scheme( ),

userinfo( ), server( ), port(

), path( ), query( ), and fragment( ) methods, there are some useful

but less-intuitive ones.

$url->path_query([newval]);The path and query components as a single string, e.g.,

/hello.php?user=21.$url->path_segments([segment, ...]);In scalar context, it is the same as

path( ), but in list context, it returns a list of path segments (directories and maybe a filename). For example:

$url = URI->new('http://www.example.int/eye/sea/ewe.cgi');

@bits = $url->path_segments( );

for ($i=0; $i < @bits; $i++) {

print "$i {$bits[$i]}\n";

}

print "\n\n";

0 {}

1 {eye}

2 {sea}

3 {ewe.cgi}$url->host_port([newval])The hostname and port as one value, e.g.,

www.example.int:8080.$url->default_port( );The default port for this scheme (e.g., 80 for

httpand 21 forftp).

For a URL that simply lacks one of those parts, the method for

that part generally returns undef:

use URI;

my $uri = URI->new("http://stuff.int/things.html");

my $query = $uri->query;

print defined($query) ? "Query: <$query>\n" : "No query\n";

No queryHowever, some kinds of URLs can't have certain components. For example,

a mailto: URL doesn’t have a

host component, so code that calls host( ) on a mailto: URL will die. For example:

use URI;

my $uri = URI->new('mailto:hey-you@mail.int');

print $uri->host;

Can't locate object method "host" via package "URI::mailto"This has real-world implications. Consider extracting all the URLs in a document and going through them like this:

foreach my $url (@urls) {

$url = URI->new($url);

my $hostname = $url->host;

next unless $Hosts_to_ignore{$hostname};

...otherwise ...

}This will die on a mailto:

URL, which doesn’t have a host( )

method. You can avoid this by using can(

) to see if you can call a given method:

foreach my $url (@urls) {

$url = URI->new($url);

next unless $uri->can('host');

my $hostname = $url->host;

...or a bit less directly:

foreach my $url (@urls) {

$url = URI->new($url);

unless('http' eq $uri->scheme) {

print "Odd, $url is not an http url! Skipping.\n";

next;

}

my $hostname = $url->host;

...and so forth...Because all URIs offer a scheme method, and all http: URIs provide a host( ) method, this is assuredly

safe.[1] For the curious, what URI schemes allow for what is

explained in the documentation for the URI class, as well as the

documentation for some specific subclasses like URI::ldap.

Queries

The URI class has two methods for dealing with query data above and beyond the

query( ) and path_query( ) methods we’ve already discussed.

In the very early days of the web, queries were simply text

strings. Spaces were encoded as plus (+) characters:

http://www.example.int/search?i+like+pie

The query_keywords( ) method

works with these types of queries, accepting and returning a

list of keywords:

@words = $url->query_keywords([keywords, ...]);For example:

use URI;

my $url = URI->new('http://www.example.int/search?i+like+pie');

@words = $url->query_keywords( );

print $words[-1], "\n";

pieMore modern queries accept a list of named values. A name and its value are separated by

an equals sign (=), and such pairs

are separated from each other with ampersands (&):

http://www.example.int/search?food=pie&action=like

The query_form( ) method lets

you treat each such query as a list of keys and

values:

@params = $url->query_form([key,value,...);

For example:

use URI;

my $url = URI->new('http://www.example.int/search?food=pie&action=like');

@params = $url->query_form( );

for ($i=0; $i < @params; $i++) {

print "$i {$params[$i]}\n";

}

0 {food}

1 {pie}

2 {action}

3 {like}Relative URLs

URL paths are either absolute or relative. An absolute URL starts with a scheme, then has whatever data this scheme requires. For an HTTP URL, this means a hostname and a path:

http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/stuff.html

Any URL that doesn’t start with a scheme is relative. To interpret a relative URL, you need a base URL that is absolute (just as you don’t know the GPS coordinates of “800 miles west of here” unless you know the GPS coordinates of “here”).

A relative URL leaves some information implicit, which you look to its base URL

for. For example, if your base URL is

http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/stuff.html,

and you see a relative URL of /also.html, then the

implicit information is “with the same scheme (http)” and “on the same host

(phee.phye.phoe.fm),” and the explicit information

is “with the path /also.html.” So this is

equivalent to an absolute URL of:

http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/also.html

Some kinds of relative URLs require information from the path of

the base URL in a way that closely mirrors relative filespecs in Unix

filesystems, where ".." means “up one

level”, "." means “in this level”,

and anything else means “in this directory”. So a relative URL of just

zing.xml interpreted relative to

http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/stuff.html

yields this absolute URL:

http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/zing.xml

That is, we use all but the last bit of the absolute URL’s path, then append the new component.

Similarly, a relative URL of ../hi_there.jpg interpreted against the absolute URL http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/stuff.html gives us this URL:

http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/hi_there.jpg

In figuring this out, start with

http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/ and the

".." tells us to go up one level,

giving us http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/. Append

hi_there.jpg giving us the URL you see

above.

There’s a third kind of relative URL, which consists entirely of a fragment, such as #endnotes. This is commonly met with in HTML documents, in code like so:

<a href="#endnotes">See the endnotes for the full citation</a>

Interpreting a fragment-only relative URL involves taking the base URL, stripping off any fragment that’s already there, and adding the new one. So if the base URL is this:

http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/stuff.html

and the relative URL is #endnotes, then the new absolute URL is this:

http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/stuff.html#endnotes

We’ve looked at relative URLs from the perspective of starting with a relative URL and an absolute base, and getting the equivalent absolute URL. But you can also look at it the other way: starting with an absolute URL and asking “what is the relative URL that gets me there, relative to an absolute base URL?”. This is best explained by putting the URLs one on top of the other:

Base: http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/stuff.xmlGoal: http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/zing.html

To get from the base to the goal, the shortest relative URL is simply zing.xml. However, if the goal is a directory higher:

Base: http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/stuff.xmlGoal: http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/hi_there.jpg

then a relative path is ../hi_there.jpg. And in this case, simply starting from the document root and having a relative path of /hi_there.jpg would also get you there.

The logic behind parsing relative URLs and converting between them and absolute URLs is not simple and is very easy to get wrong. The fact that the URI class provides functions for doing it all for us is one of its greatest benefits. You are likely to have two kinds of dealings with relative URLs: wanting to turn an absolute URL into a relative URL and wanting to turn a relative URL into an absolute URL.

Converting Absolute URLs to Relative

A relative URL path assumes you’re in a directory and the path elements are relative to that directory. For example, if you’re in /staff/, these are the same:

roster/search.cgi /staff/roster/search.cgi

If you’re in /students/, this is the path to /staff/roster/search.cgi:

../staff/roster/search.cgi

The URI class includes a method rel( ), which

creates a relative URL out of an absolute goal URI object. The newly

created relative URL is how you could get to that original URL, starting

from the absolute base URL.

$relative = $absolute_goal->rel(absolute_base);The absolute_base is the URL path in

which you’re assumed to be; it can be a string, or a real

URI object. But $absolute_goal must

be a URI object. The rel( ) method

returns a URI object.

For example:

use URI;

my $base = URI->new('http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/zing.xml');

my $goal = URI->new('http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/hi_there.jpg');

print $goal->rel($base), "\n";

../hi_there.jpgIf you start with normal strings, simplify this to URI->new($abs_goal)->rel($base), as

shown here:

use URI;

my $base = 'http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/thingamajig/zing.xml';

my $goal = 'http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/hi_there.jpg';

print URI->new($goal)->rel($base), "\n";

../hi_there.jpgIncidentally, the trailing slash in a base URL can be very important. Consider:

use URI;

my $base = 'http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/englishmen/blood';

my $goal = 'http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/englishmen/tony.jpg';

print URI->new($goal)->rel($base), "\n";

tony.jpgBut add a slash to the base URL and see the change:

use URI;

my $base = 'http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/englishmen/blood/';

my $goal = 'http://phee.phye.phoe.fm/englishmen/tony.jpg';

print URI->new($goal)->rel($base), "\n";

../tony.jpgThat’s because in the first case, “blood” is not considered a directory, whereas in the second case, it is. You may be accustomed to treating /blood and /blood/ as the same, when blood is a directory. Web servers maintain your illusion by invisibly redirecting requests for /blood to /blood/, but you can’t ever tell when this is actually going to happen just by looking at a URL.

Converting Relative URLs to Absolute

By far the most common task involving URLs is converting relative URLs to absolute

ones. The new_abs( ) method does

all the hard work:

$abs_url = URI->new_abs(relative,base);

If rel_url is actually an absolute URL,

base_url is ignored. This lets you pass all

URLs from a document through new_abs(

), rather than trying to work out which are relative and which

are absolute. So if you process the HTML at

http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/ and you find a link

to pperl3/toc.html, you can get the full URL like

this:

$abs_url = URI->new_abs('pperl3/toc.html', 'http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/');Another example:

use URI;

my $base_url = "http://w3.thing.int/stuff/diary.html";

my $rel_url = "../minesweeper_hints/";

my $abs_url = URI->new_abs($rel_url, $base_url);

print $abs_url, "\n";

http://w3.thing.int/minesweeper_hints/You can even pass the output of new_abs to the canonical method that we discussed earlier, to

get the normalized absolute representation of a URL. So if you’re

parsing possibly relative, oddly escaped URLs in a document (each in

$href, such as you’d get from an

<a href="..."> tag), the

expression to remember is this:

$new_abs = URI->new_abs($href, $abs_base)->canonical;

You’ll see this expression come up often in the rest of the book.

[1] Of the methods illustrated above, scheme, path, and fragment are the only ones that are

always provided. It would be surprising to

find a fragment on a mailto:

URL—and who knows what it would mean—but it’s syntactically

possible. In practical terms, this means even if you have a

mailto: URL, you can call

$url->fragment without it

being an error.

Get Perl & LWP now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.