When we create and use scoped discussion zones, we’re dealing with the information architecture of the conferencing environment as a whole. Now let’s switch lenses and focus more narrowly on information architecture as it relates to individual messages and threads. This may strike you as odd, but if you think in engineering terms, a message is really a kind of object that stores some data and presents an interface that gives users access to that data. Many of us are comfortable with the idea that software objects should properly package their data. But we rarely stop to think that message objects should too.

The techniques for packaging messages aren’t difficult, but neither are they automatic. Our messaging tools don’t force us to write effective titles, compartmentalize messages, choose appropriate scopes, or layer the information we present. Why should you develop these habits, then? Again I invoke the principle of enlightened self-interest. Quite often a document that I mail or post is also intended for my own future reference. It’s to my own advantage to package it in a way that will aid retrieval. Of course, the document is also an effort of communication, invested in hope of some kind of return—a useful reply, a request honored, or simply good will. You can regard good packaging as nothing more, and nothing less, than a calculated bid to maximize your return on an investment of communication effort. Here are some guidelines for packaging mail and news messages.

Subject headers are the titles of mail and news messages. When you scan the contents of an inbox folder or a newsgroup, or when you scan the results of a search of an email archive or a newsgroup, message titles are your best clues about what messages contain. For example, my Sent mail folder at this moment contains a number of months-old messages between me and Mark Stone, an editor at O’Reilly. When I need to refer to the one in which I raised an issue about my contract for this book, I want to see a title like “contract issues” rather than one like “re: re: re: more stuff.”

If I raised the issue myself, it was my responsibility to write that title. But if Mark raised the issue, perhaps as part of a larger message bearing the catch-all title “more stuff,” I can still seize the packaging initiative by quoting the contract-related material in a reply that I entitle “contract issues.” Note that when either party upgrades the quality of a message header, both benefit—because both are now more likely to be able to find that document in their local message stores.

The same principle governs the discussion realm. A posting that launches a new thread should carry a title that accurately describes the message. A response, likewise, should carry a title that accurately describes what it adds to the discussion. In practice, that often won’t happen. The path of least resistance will often lead to a cascade of “re: re: re: re:” responses. But anyone, at any point, can add value to the discussion by writing a meaningful message title. Such a message advertises itself, and its surrounding thread context, more effectively to anyone who is scanning or searching the newsgroup. There’s another subtle benefit too. A discussion thread is, after all, an online meeting. Agendas drift in online meetings just as they do in face-to-face meetings. Writing an effective title can help clarify the agenda.

A message that raises two unrelated issues might be better packaged as two distinct messages. Programmers will recognize this strategy right away. A set of small, single-purpose, descriptively named functions is more useful, and not much harder to produce, than a monolithic do-everything routine. Yet few programmers—never mind civilians—carry this discipline into the messaging domain. There are good reasons to do so. This book divides into sections and subsections because each part fulfills a purpose suggested by its title. You would find an undifferentiated stream of text vastly less useful. The same principle can and should apply to mail and news messages.

Won’t two mail messages double the demand you are making on my attention? Not at all. It takes hardly any longer to absorb the same quantity of text when it comes in two packages instead of one. The effort you invest in creating two packages spares me the effort required to mentally disentangle unrelated matters raised in a single message. It means that I can more easily file each message in an appropriate folder. And then there’s the issue of scope again. The two messages might properly belong in different newsgroups or might have been best sent to slightly different sets of email recipients. Messages are cheap; attention is precious. There’s a limited fund of attention available for the messages you write. Conserve it with thoughtful packaging.

Newsgroups and other threaded discussion systems grow inverted trees of messages and responses. Although the tools usually enforce no policy as to how these trees grow, groups can create their own policies to achieve several kinds of information-management goals.

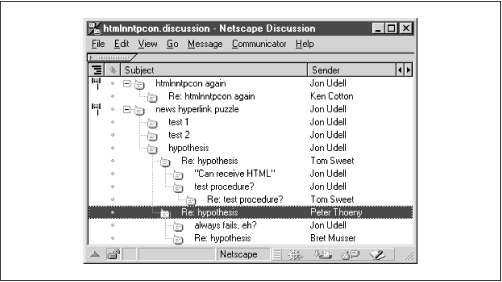

One useful strategy, often neglected, is to use thread hierarchy as a tool to clarify a discussion. For example, Figure 4.2 shows a snapshot of one of my public discussions. The thread entitled “news hyperlink puzzle” described a Netscape newsreader bug, offered two test cases and a hypothesis, and invited participants to try the tests and comment on the hypothesis.

At the moment this snapshot was taken, here’s what had emerged:

Tom reported that he could not confirm the hypothesis. He also raised a tangential issue about Communicator’s default HTML setting.

Peter reported that his test also refuted the hypothesis.

Bret, who was not running Communicator and so could neither confirm nor deny the hypothesis, contributed an observation about “test 1” from the perspective of the Lynx browser.

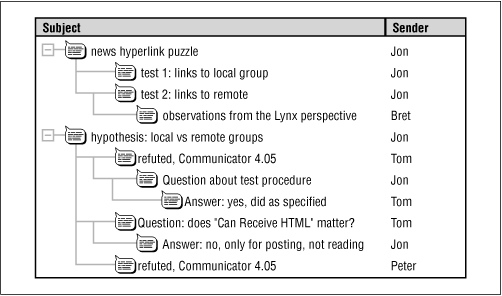

How much of the sense of that discussion emerges from an inspection of this picture? Almost none. Now suppose the picture instead looked like Figure 4.3.

Here you can see exactly what’s going on. The outline view does what each level of a layered information system should do. It tells its own story, summarizes the next layer, and helps the reader decide how—or even whether—to explore the next layer. Note that most of the effect here results from rewritten titles. There are just two structural changes. Tom’s reply is divided into its two logical components—the refutation and a tangential query. That move enables the outline structure to clarify follow-on discussion of both matters. And Bret’s reply now attaches to “test 2” where it logically belongs. That move is subtle but worthwhile. There’s a strong tendency in threaded discussions to reply to the last message in a series. Often, though, your reply should logically attach farther up the tree—perhaps even to several different nodes.

Does casual business communication merit this kind of effort? I think so. Why bother to collaborate online if you’re not serious about the value of the information you give and receive? Habits of effective titling and layering, once acquired, cost little time and add enormous value to a discussion.

Discussion can be wonderful, but at some point decisions have to be made, actions taken, deadlines met. Some commercial groupware systems claim to be able to help drive discussion toward consensus, but you might want to consider a simpler, cheaper, and less formal approach. Suppose at the beginning of a project you create a thread with this structure:

Project X

| Discussion |

Issue 1

Issue 2

| Decisions |

I call this kind of thread a lightweight newsgroup because anyone can create one. There’s none of the administrative overhead normally required to launch a newsgroup, advertise its existence, and make sure everyone who ought to subscribe does. A thread intended as a lightweight newsgroup can simply appear in the flow of an existing well-known newsgroup.

The top-level message, entitled “project X,” explains the policy for this thread. The second-level messages, entitled “discussion” and “decisions,” are just structural placeholders. Under “discussion,” the messages “issue 1” and “issue 2” introduce two matters that are open for discussion. As the top-level policy statement explains, all discussion of each issue should begin at level 4—that is, as a reply to “issue 1” or “issue 2.” Each level 4 reply is considered to be a top-level posting in a discussion of the issue named at level 3; additional structures attach to these nodes in the normal way.

What about the “decisions” node? The group leader, who probably also wrote the policy statement and is the authoritative decision-maker for the group, will post a reply under the “decisions” thread for each issue that is decided.

This protocol is fundamentally not much different from what typically goes on in conference rooms. An agenda is set; debate ensues; decisions are recorded. In a newsgroup you give up face-to-face contact—or voice contact, when some participants are on the speaker phone. You gain the ability to collaborate on an equal basis from anywhere, at any time, with full access to all your information sources and no pressure to shoot from the hip. It’s true that the messaging tools can’t enforce the rules of engagement. Nothing prevents an unauthorized posting to the “decisions” node. Is that a problem? I don’t think so. In real conference rooms, people don’t usually leap to the whiteboard and scribble rogue decisions. Should that ever happen, there’s always the eraser—in NNTP terms, the message-canceling function (see the following tip). From this perspective a newsgroup is nothing more, and nothing less, than a whiteboard that isn’t bound by time and space and that produces a permanent, searchable transcript.

Note

You can use your newsreader to cancel messages—but only those that you yourself have posted. More specifically, your newsreader must be configured to transmit the same email address in the From: header as appears on the message you want to cancel. Once you cancel a message, it’s gone from the server. However, if the message has been replicated to a local message store, using the offline features of the Microsoft or Netscape newsreaders, the local copy will remain.

Netscape Collabra procedure: Edit → Cancel Message.

Outlook Express procedure: Compose → Cancel Message.

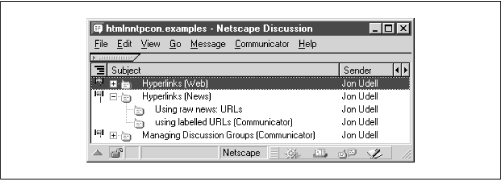

I began developing the NNTP examples for this book in a newsgroup—readable by the world, writable only by me—where I documented how to make best use of the collaborative features of the Microsoft and Netscape newsreaders. Figure 4.4 shows an early snapshot of that newsgroup.

It’s a simple structure—just a set of topics, each of which expands to reveal a set of examples. Since I’m the only one who can post to the group, I can guarantee that the structure stays clean and orderly. This approach isn’t going to replace conventional web publishing. But it’s good enough for many purposes, including this one. It’s something that anyone with a newsgroup password can do. And because it’s newsgroup-based, there’s another advantage that you don’t get with conventional web publishing. When I add new examples, or modify existing ones (by canceling and reposting), your newsreader will flag the changes as unread messages and direct your attention to them. Web archives have to work hard to achieve this effect; newsgroups do it automatically.

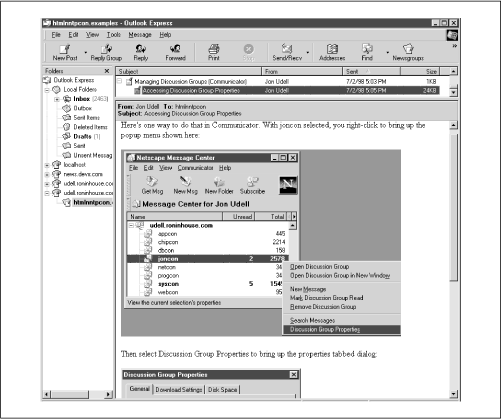

Each message in this newsgroup was an HTML document. As Figure 4.5 shows, these messages were good examples of how HTML-friendly newsgroups can be used not only for discussion, but also as a way to explain and demonstrate things using words and pictures.

Get Practical Internet Groupware now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.