Chapter 4. Establishing the Why with Product Vision and Strategy

What you’ll learn in this chapter

The difference between mission, vision, and values

How to create and communicate your product vision

How to develop a product strategy for achieving your vision

The importance of defining metrics for success

A product vision should be about having an impact on the lives of the people your product serves, as well as on your organization.

It’s easy to get overwhelmed by the various concepts and terminology surrounding product development, and even more when you start to consider the terminology involved with strategy.

There are mission statements, company visions, values, goals, strategy, problem statements, purpose statements, and success criteria. Further, there are acronyms like KPI and OKR, which also seem potentially useful in guiding your efforts. How do you know which ideas apply to your situation, and where to start?

Whether your organization is mission-, vision-, or values-driven (or a combination thereof), these are all considered guiding principles to draw from and offer your team direction. For the purposes of this book, we’ll establish definitions for mission, vision, and values, so we have a common language. Bear with us if you have different definitions of them yourself.

Mission Defines Your Intent

A mission is not what you value, nor is it a vision for the future; it’s the intent you hold right now and the purpose driving you to realize your vision. A well-written mission statement will clarify your business’s intentions. Most often we find mission statements contain a mix of realism and optimism, which are sometimes at odds with each other.

There are four key elements to a well-crafted mission statement:

- Value

What value does your mission bring to the world?

- Inspiration

How does your mission inspire your team to make the vision a reality?

- Plausibility

Is your mission realistic and achievable? If not, it’s disheartening, and people won’t be willing to work at it. If it seems achievable, however, people will work their tails off to make it happen.

- Specificity

Is your mission specific to your business, industry, and/or sector? Make sure it’s relevant and resonates with the organization.

Here are two example missions. Can you guess the company for either?

Company A

To refresh the world...

To inspire moments of optimism and happiness...

To create value and make a difference.

Company B

To inspire and nurture the human spirit—one person, one cup, and one neighborhood at a time.

Company A is Coca-Cola, and Company B is Starbucks. While these missions may also be considered marketing slogans due to the size and popularity of each company, it’s important to note their aspirational context.

Another aspect of mission that’s often overlooked is that it has to reflect what you do for someone else. That someone else is typically not your shareholders, but your customers.

Vision statements are very often conflated with mission. We’ve seen many company vision statements that are actually mission statements. Vision statements are a challenge to not be self-centered to “be the best ___.”

Vision Is the Outcome You Seek

A company vision should be about a longer-term outcome that has an impact on the lives of the people your product serves, as well as on your organization. Vision is why your organization exists, and it can be decomposed into the benefits you hope to create through your efforts—for both the world and your organization. It can be a literal vision of the future, such as “create a world where you can belong anywhere” (Airbnb) or “become a multi-planet species” (SpaceX), or “A just world without poverty” (Oxfam).

In its simplest form, a company vision is a statement that paints a future reality or world. A solid vision statement will address, at minimum, these two aspects:

The target customer—the who?

The benefit or need(s) addressed—the why?

Some might include a third:

What makes it unique—how is it different?

Let’s take the earlier example from Airbnb:

Create a world where you can belong anywhere.

Who? You, the customer!

What? A sense of belonging.

How it’s different? Anywhere in the world, even if you don’t feel like you belong there.

Values Are Beliefs and Ideals

Values are also intended to guide behaviors. Values shape that ambiguous word thrown around company HR departments, culture—how people behave when no one is watching. Your organization’s values may inform your vision or mission, and how you go about achieving it.

Values are often referred to as your compass. A compass tells you which direction is north or south, but not which direction to travel; you must make that decision yourself. Likewise, your values will help you determine what’s right or wrong for your business, but not which direction to take—that’s where your vision and mission come in.

Your vision is your ultimate destination, and your mission tells you which direction to follow in order to reach that destination. Take InVision App’s values as an example: “Question Assumptions. Think Deeply. Iterate as a Lifestyle. Details, Details. Design is Everywhere. Integrity.” They give employees a guide for how to make decisions during their work.

Here’s a simple example: if you were a buyer at Whole Foods Market, a large organic grocery store primarily in the United States (and recently acquired by Amazon), and you followed the value “We Sell the Highest Quality Natural and Organic Products Available,” would you select foods that contain artificial ingredients to stock in the stores? We would hope not, as that value ought to tell you that’s the wrong direction for the company.

Most roadmaps provide a lot of detail about what you intend to deliver without the context of a vision, mission, or values. When you first establish that foundation by outlining your vision and your strategy for pursuing it, the details you provide—within the themes, features, functions, deliverables, services, activities, and so on—will paint a clearer picture to all the stakeholders of your roadmap. They will support and contribute to that foundation, rather than carrying the burden themselves in hopes that stakeholders will piece everything together on their own.

With these concepts defined, now let’s talk more in depth about how they inform your product roadmap.

Product Vision: Why Your Product Exists

Product vision clarifies why you are bringing a product to market in the first place, and what its success will mean to the world and to the organization. The vision is the raison d’être of the entire effort, and forms the basis of the roadmap. As we mentioned previously for vision, it is the destination you plan to reach.

Capella University was an early innovator in online higher education. Its initial success came from delivering high-quality online learning experiences, but as others began to follow suit, they needed to differentiate their offerings.

A key insight came when they discovered that even one personal connection dramatically reduced the student’s likelihood of dropping out, and that online access to financial aid and similar resources reduced volumes of phone calls to support hotlines and resulted in more satisfied students. This led them to a product vision of “delivering the entire university experience successfully over the web,” according to Jason Scherschligt, who managed Capella’s online experience. Critically, this vision included not just access to academic learning spaces, but also administrative functionality, support resources (tech support, a career center, writing resources, disability services, and an online library), and a private network of fellow learners, faculty, and alumni.

“The vision work was critical to the success of this initiative,” explains Scherschligt. “While it started as just an upgrade of an ERP [Enterprise Resource Planning] portal, it became a much more valuable property for the organization through strong vision and storytelling. We initially conceived of the initiative in 2008, launched the first release in June of 2009, and it remains at the heart of the Capella online experience.”

A clear product vision made it straightforward for Scherschligt and his team to tie every decision and every priority to the result they wanted for students—a full university experience via the web—and to develop what we call “themes” based on those desired outcomes.

It’s likely that someone, somewhere in your organization, has a product vision. This does nobody any good if it remains stuck in that person’s head. If your CEO has a vision but she doesn’t communicate it to the rest of the organization, you can bet there will be struggles when it comes time to make decisions and she’s not present.

If your organization has multiple products, the product vision is likely different from the corporate vision, though still supportive of and derived from it. For example, Google Search’s product vision is “to provide access to the world’s information in one click.” It’s easy to see how that comes directly from the broader company mission: “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

To create a product vision we suggest starting with Geoffrey Moore’s “Value Proposition template” (also known as the “Elevator Pitch template”) from his book, Crossing the Chasm (HarperBusiness). We have adapted it slightly for use in product roadmapping.

Value Proposition Template

For: [target customer]

Who: [target customer’s needs]

The: [product name]

Is a: [product category]

That: [product benefit/reason to buy]

Unlike: [competitors]

Our product: [differentiation]

Example for Our Wombat Hose

For homeowner landscape enthusiasts

Who need a reliable hose that’s survives repeated use

The Wombat Garden Hose

Is a water delivery system

That offers a reliable operation under any conditions

Unlike the competition

The Wombat Garden Hose is indestructible and offers uninterrupted water delivery

Then take this one step further and tie this sentence to your company’s strategy by adding a description:

Supports our: [objective(s)]

Finally, to pare this down to a vision statement, try to compress that information into the following:

A world where the [target customer] no longer suffers from the [identified problem] because of [product] they [benefit].

Wombat Garden Hose Example:

A world where American landscape enthusiasts [target customer] can have a more predictable and automatic [identified problem] watering system that can perfect their lawns [benefit] with an effective water delivery system [product].

This focuses on the who (target customer), the what (problem it solves), and the why (benefit they receive). Additionally, it also helps to write out all the preceding information in order to arrive at a clear product vision. We realize this can seem formulaic, and there is a downside to a vision statement that’s plug-and-play when it should be unique and specific to your product and business. However, this template is a great tool when you are starting from scratch, or if you have established a product vision and need a gut-check to determine if you have something robust to drive your product strategy and roadmap.

Some product teams will pare this even further to just the product benefit and product differentiator.

To [benefit realized] by [product differentiator]

Wombat Garden Hose Example:

To perfect American lawns by perfecting water delivery.

“When done well, the product vision is one of our most effective recruiting tools, and it serves to motivate the people on your teams to come to work every day. Strong technology people are drawn to an inspiring vision; they want to work on something meaningful.”

Marty Cagan, founder of Silicon Valley Product Group and author of Inspired

Duality of Company and Customer Benefit

While we’re discussing vision, let’s not forget the organization’s perspective. A vision of company success might be to “operate the best omni-channel specialty retail business in America” (Barnes & Noble) or to be “a major platform player like Salesforce and Hubspot” (Contactually). An internal vision like this is just as important as an externally motivated one. They work together symbiotically to make something great.

Acknowledging that you need to make money to stay in business and deliver on your vision of a better world is healthy, and it allows you to have open discussions of ideas that serve both or only one of those visions.

One caution about internal vision statements, however, is that they can become too company-focused and fail to include the customer. Microsoft’s famous vision of “a personal computer on every desk running Microsoft software” from the 1980s is a great example. At that time, it described a future aspirational world where the benefit to Microsoft is apparent, but inherent to that is a benefit to each individual by having a computer at their desk. One could argue that this vision fails is in service to Microsoft’s customers and is too centric to Microsoft. As we’re writing this book using a combination of MacBooks, tablets, and desktop computers, we’re fully aware of the benefit of a personal computer. Today that benefit is clear, but in 1980s it came with an implied customer benefit, so it worked. Today that vision could fall short since it’s too Microsoft-centric and times have changed with respect to a computer on everyone’s desk (it’s now in your pocket, and soon to be ubiquitous). As you can imagine, it no longer is Microsoft’s vision as of the writing of this book.

Product Strategy: How You Achieve Your Vision

Your product strategy is the bridge that connects your high-level vision to the specifics of your roadmap. And for many companies, the product strategy is the main contributor to their overall business strategy. This makes it crucial that you use product strategy as a starting place for your roadmap.

If your product vision includes meeting the needs of a group of people, then your product strategy simply makes that more explicit and concrete by explaining a bit about how. Usually, this takes the form of objectives. For example, SpaceX hopes to meet its lofty (literally) vision of “make going to Mars a reality in your lifetime.”

To ensure that its relationship marketing platform is financially viable, Contactually has defined business objectives for increasing the number of sales leads, average sale price, trial conversion, and customer retention.

Furthermore, Contactually has effectively combined internal and external business objectives in its themes. Its business strategy is to grow in “the real estate professional market for the coming year,” while planning “to expand into other segments in the future.” This business strategy allows Contactually to combine the market’s needs with its own. Let’s convert this to product strategy, and see how it’s separate, but very related to, business objectives.

Objectives and Key Results

Identifying business objectives that tie to your vision is critical to making that vision a reality. It’s great to say, “We imagine a world where instant teleportation from one location to another makes travel options effortless.” However, if you don’t have specific objectives to hit along the way, that vision will be challenging to implement because there will be too many different product, technology, and business directions to take to get there. (Though if you do make teleportation a reality, please tell us; we collectively have too many frequent flyer miles!)

Often referred to as objectives and key results (OKRs) are a great way to pair your business objectives with success criteria. The premise of the OKR framework is that objectives are specific qualitative goals, and key results are quantitative measures of progress toward achieving those objectives. The first implementation of OKRs was by Andrew Grove at Intel in the early 1980s, as he recounts in his book High Output Management (Vintage). Many well-known organizations—Google, Uber, Zynga, and LinkedIn, to just name a few—utilize OKRs in their operations today. Christina Wodtke, author of Radical Focus (Boxes & Arrows), adopted the OKR framework to set personal goals and also wrote a short ebook dedicated to OKRs for products.

Here are a few guidelines on OKRs as they apply to product roadmapping:

Everything on the roadmap must be tied to at least one of your objectives.

Stick to a manageable number of objectives; from our experience and research, fewer than five seems to be most effective.

Focus on outcomes, not output.

We’ve interviewed dozes of teams and have found that while every product team has unique metrics, there are some patterns.

The 10 universal business objectives

We’ve distilled every business objective we’ve encountered into a list of 10 that can apply to just about any product, regardless of whether it is a hardware, software, or service product. Whenever we ask “why” enough times about a proposed roadmap theme, feature, solution, program, or other initiative, it always seems to come back to one of these underlying objectives.

For each of these universal objectives, we’ve listed a Wombat Garden Hose theme, solution, or other initiative that might have been motivated by that underlying objective. We’ve also suggested a key result that could be used to measure success in reaching that objective.

Your product is likely to have an organizational objective (or two, or five) that resembles any of these. Note that these are not customer-facing goals, yet internal and customer-focused objectives should be mutually reinforcing (we’ll talk more about customer-facing goals in Chapter 5). Bryan Dunn, VP Product Management at Localytics, poses a great question, “What kind of product do we need to attain those business objectives?” For example, work on improved usability will increase customer lifetime value (LTV) by decreasing churn. The goal for the customer is a better user experience; the goal for the product is decreased churn and increased LTV. The duality we mentioned previously is balanced.

| Universal Objective | Wombat Theme or Solution | Wombat Key Result |

|---|---|---|

Sustainable Value | ||

Support the product’s core value | Indestructibility | Must-have for first ship |

Create barriers to competition | Branded proprietary materials | Must-have for first ship |

Growth | ||

Grow market share | Competitive trade-in program | 5% share in first season |

Fulfill more demand | Bring another plant online | Reduce out-of-stock incidents to <10% |

Develop new markets | Contractor version | 200k contractor unit sales in first season |

Improve recurring revenue | Consumable add-ons | 65% repurchase rate |

Profit | ||

Support higher prices | 10-year warranty | 20% price increase does not reduce unit volume >5% |

Improve lifetime value | Proprietary connectors discourage mixing brands | Average LTV +30% in second season |

Lower costs | Bring packaging in house | Reduce finished product cost by 15% in 12 months |

Leverage existing assets | Develop white-label version for other brands | Generate >$1m with unused plant capacity in first 12 months |

Let’s take this back to the Contactually example. It expresses its product strategy for the next year in three objectives, each with measurable success criteria:

“launch new features or services that realtors will pay more money for,”

“improve the feature sets of our existing plans so more users will purchase,”

“improve our team functionality to better meet the needs of team leads.”

Each of these themes is tied to an objective that can then be measured by specific key results, and their roadmap reflects this. This internal objectives-driven approach to roadmapping makes direction crystal-clear for internal teams. In this case, rather than being based on customer needs, each objective focuses on a measurable business benefit that work is designed to achieve (higher average sale price or higher renewal rate, for example). This “outcome-based” roadmap makes clear why certain work is important, even allowing Contactually to leave placeholders for features yet to be conceived. This framework also makes room for things not often included on product roadmaps, such as bug fixes and infrastructure enhancements, by providing the business justification for that work.

See Chapter 5 and Chapter 6 for more information on identifying and solving for customer needs.

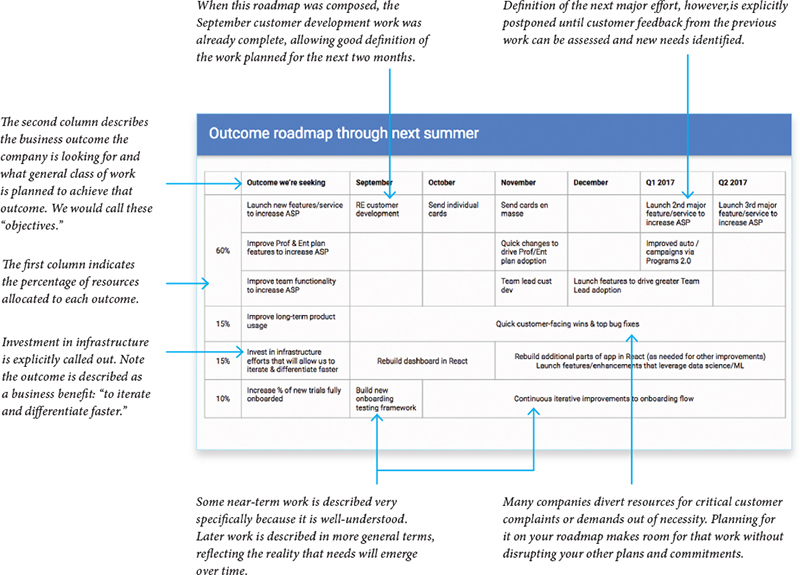

This Contactually roadmap is designed to support internal discussions about business objectives and how much of the company’s resources are allocated to each. The specific deliverables in each month are comparatively downplayed as those are the outputs (more on this in a minute).

A roadmap based primarily on internal business objectives would not, of course, be appropriate for sharing with customers or channel partners. Customers are not interested in your internal metrics or your effort to develop a new technical platform; they care only about how you will add value to them or their business. These external stakeholders are equally uninterested in your resource allocation—unless it shows them that you are focusing a substantial set of resources on their favorite problem or feature idea.

All this begs the question: how you do know if you have achieved those objectives? You have metrics to track your progress. And who doesn’t love a good metric?

Figure 4-1. Contactually’s outcome-based roadmap

Key results (and metrics)

One of the most important things a product pro must do before releasing a product is define how the success of that product will be measured, or its key performance indicators (KPIs). These KPIs are often the metrics you are using to measure the key results from your OKRs. They are data that give you meaningful feedback on how your product is doing. The process of choosing which metrics to capture can be complicated, and you’ll benefit greatly from exposure and experience. For the new product person, we have one key piece of advice here: find a balance with the amount of data you analyze. Three to five objectives are usually sufficient, and the metrics to measure them shouldn’t be exponential. Sometimes you might have only one metric. (Your mileage may vary, but remember that the more objectives, the less focus you can likely give them. See Chapter 7 if you need help prioritizing.) If it takes you longer than one hour to review your data at a high level each week, we would argue you’re trying to track and interpret too many metrics. Data analysis is an important part of your product roadmapping process, but you don’t want it to be so onerous that it consumes too much time.

As your product grows and as your product team gets better and better at testing solutions and improving functionality, your approach to data collection can always become more sophisticated. All that said, you also have to make sure to define enough success metrics to actually be able to capture valuable insights. Just tracking revenue is not going to cut it if you want to create a product that provides lasting value. A metric like revenue alone will certainly tell you something’s not working, but only when it’s too late. In our experience, starting with a handful of KPIs is a good and manageable place to land.

In addition to specific product metrics, incorporating customer feedback can give you a more robust picture of your users’ behaviors. You’ve probably heard of the net promoter score as a quantitative measure of qualitative customer feedback. There’s no substitute for talking to your customers face-to-face and listening to them talk about how they use, like, and/or dislike your product. This combination of quantitative and qualitative data is powerful when executed well. Once you have a reliable system for defining what to track and analyzing your results, you can use that information to inform and prioritize your roadmap.

Tying this back to Contactually’s objective of “improve the feature sets of our existing plans so more users will purchase,” key results here could be “an increase in user base by 5% over the course of a specific timeframe” (a quarter, year, etc.) and feature-specific metrics such as “time to compose and send an email is reduced by 10%,” indicating that the usability of that part of the product has been improved. Note that there can be multiple key results to each objective, as it may take different measures to determine whether an objective is met.

Outcome Versus Output

Well-known Harvard Business Review blogger Deb Mills-Scofield gives a great example distinguishing what you’re delivering (output) from the reasons why (outcome): “Let’s define outputs as the stuff we produce, be it physical or virtual, for a specific type of customer—say, car seats for babies. And let’s define outcomes as the difference our stuff makes—keeping your child safe in the car.” Her summary is the best way to keep these terms straight: “Outcomes are the difference made by the outputs.”

We’ve said several times that your roadmap should focus on outcomes over outputs. Nonetheless, sometimes you will be required to provide more concrete detail about what you plan to deliver as part of your strategy for achieving your vision. SpaceX showed diagrams of spacecraft designs and videos of Mars landings to provide a taste of what it intends to deliver. Video game companies like Nintendo are famous for cinematic trailers designed to whet players’ appetites without committing to details. Electronic component manufacturers frequently provide specs months or even years in advance to their OEM partners, on the other hand, so the level of detail will depend on your roadmap’s intended audience.

The risk of an output-focused roadmap often equates to a product team that releases feature after feature, and no tie back to the reason for those features. A feature factory is the term often used to describe such teams. You released a bunch of features; the key question becomes: did they achieve the outcome you were seeking?

Timing

When it comes to dates in your roadmap, there is a lot of contention. Many stakeholders are looking to the roadmap to tell them exactly what they can expect and when. However, that type of artifact is not a roadmap—it’s a project plan or a release plan. Michael Salerno, VP of Product at Brainshark, puts it simply: “A roadmap is not a release plan. A roadmap is a sequence of stakeholder priorities and requires concept feasibility for delivery. A release plan requires rigorous scope definition and engineering capacity planning.”

This still doesn’t exempt a roadmap from including timeframes, though; in fact, we listed timeframes as an essential component of product roadmaps in Chapter 2. But as Jim Garretson, Director of Product at Candescent Health, explains, “We don’t tie expectations to distant roadmap deadlines. The roadmap has to tell the product story, but it doesn’t have to get the days right.” So, rather than specific dates and features, we recommend timeframes that are less specific than January 2017, or even Q2 2018. Loose timeframes like Now, Next, and Later can still satisfy the teams and stakeholders without offering specific delivery dates. Save those specifics for the release and project plans!

We do realize that in some instances your product must be out the door by a certain date; for example, when your software is embedded into another product with strict production deadlines, such as having initial software loaded onto a television. But we still hold that this level of specificity should be at the project or release plan level, and not on the roadmap.

Business Objectives

Musk begins his discussion of strategy by outlining the key problem with getting people to Mars: money. He estimates it would currently cost around $10 billion per person. There is therefore “no overlap between people who want to go and people who can afford to.” To make emigration to Mars market-viable, SpaceX would have to “drive the cost to the equivalent to a house in the US—about US $200,000.” That sounds like a business objective with a built-in key result.

Themes

Musk then asks, for this strategy to be viable, what would need to be true? His team has done the research and defined the themes this way:

Full spacecraft reusability

Refueling in orbit

Propellent production on Mars

Right propellant

These four themes don’t describe the specific technology or solution, but are all subgoals of the affordability objective. Each of these subgoals can also be a theme (we’ll discuss subthemes further in Chapter 6) that can become part of the roadmap.

Key Results

The key results for the objectives tied to the first theme of “Full spacecraft reusability” could be:

The overall market cost is $200,000 or lower.

The reusability of rocket transportation is 90% or greater.

Tons of propellant can be produced on Mars.

Summary

Guiding principles forming a vision of the future for your customer and your organization, and a strategy for achieving them, are essential ingredients of a compelling roadmap. Framing the timing and deliverables for your product within these buckets will help you establish, explain, and gain alignment on your roadmap.

Splitting the strategy portion of your roadmap into objectives and key results will allow you to direct your product development efforts toward measurable outcomes rather than specific outputs such as features and functions. Focus your measurement efforts on fewer than five objectives that will make the most difference to the success of your customer and organization.

In Chapter 5 and Chapter 6 we’ll cover how to discover and focus on solving for these key customer needs.

Get Product Roadmaps Relaunched now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.