The little dance of declaring a function before calling it (Example 1-2) may seem rather absurd, but it is of tremendous importance in the C language, because it is what allows a C program to be arbitrarily large and complex.

As your program grows, you can divide and organize it into multiple files. This kind of organization can make a large program much more maintainable — easier to read, easier to understand, easier to change without accidentally breaking things. A large C program therefore usually consists of two kinds of file: code files, whose filename extension is .c, and header files, whose filename extension is .h. The build system will automatically “see” all the files and will know that together they constitute a single program, but there is also a rule in C that code inside one file cannot “see” another file unless it is explicitly told to do so. Thus, a file itself constitutes a scope; this is a deliberate and valuable feature of C, because it helps you keep things nicely pigeonholed.

The way you tell a C file to “see” another file is with the #include directive. The hash sign in the term #include is a signal that this line is an instruction to the preprocessor. In this case, the word #include is followed by the name of another file, and the directive means that the preprocessor should simply replace the directive by the entire contents of the file that’s named.

So the strategy for constructing a large C program is something like this:

- In each .c file, put the code that only this file needs to know about; typically, each file’s code consists of related functionality.

- In each .h file, put the function declarations that multiple .c files might need to know about.

- Have each .c file include those .h files containing the declarations it needs to know about.

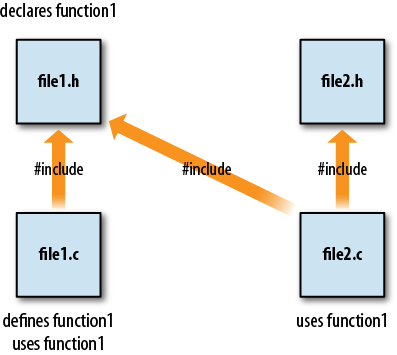

So, for example, if function1 is defined in file1.c, but file2.c might need to call function1, the declaration for function1 can go in file1.h. Now file1.c can include file1.h, so all of its functions, regardless of order, can call function1, and file2.c can also include file1.h, so all of its functions can call function1 (Figure 1-2). In short, header files are a way of letting code files share knowledge about one another without actually sharing code (because, if they did share code, that would violate the entire point of keeping the code in separate files).

But how does the compiler know where, among all these multiple .c files, to begin execution? Every real C program contains, somewhere, exactly one function called main, and this is always the entry point for the program as a whole: the compiler sets things up so that when the program executes, main is called.

The organization for large C programs that I’ve just described will also be, in effect, the organization for your iOS programs. (The chief difference will be that instead of .c files, you’ll use .m files, because .m is the conventional filename extension for telling Xcode that your files are written in Objective-C, not pure C.) Moreover, if you look at any iOS Xcode project, you’ll discover that it contains a file called main.m; and if you look at that file, you’ll find that it contains a function called main. That’s the entry point to your application’s code when it runs.

Furthermore, your iOS programs consist not only of your code files and their corresponding .h files, but also of Apple’s code files and their corresponding .h files. The difference is that Apple’s code files (which are what constitutes Cocoa) have already been compiled. But your code must still #include Apple’s .h files so as to be able to see Apple’s declarations. If you look at an iOS Xcode project, you’ll find that any .h files it contains by default, as well as its main.m file, contain a line of this form:

#import <UIKit/UIKit.h>

That line is essentially a single massive #include that copies into your program the declarations for the entire basic iOS API. Moreover, each of your .m files #imports its corresponding .h file, including whatever the .h file #imports. Thus, all your code files include the basic iOS declarations.

For example, earlier I said that CGPoint was defined like this:

struct CGPoint {

CGFloat x;

CGFloat y;

};

typedef struct CGPoint CGPoint;After the preprocessor operates on all your files, your .m files actually contain that definition of CGPoint. (In Xcode 3.2.x, you can even choose Build → Preprocess to confirm that this is true.) And that is why your code is able to use a CGPoint!

The #import preprocessor directive is not mentioned in K&R. It’s an Objective-C addition to the language. It’s based on #include, but it is used instead of #include because it (#import) contains some logic for making sure that the same material is not included more than once. Such repeated inclusion is a danger whenever there are many cross-dependent header files; use of #import solves the problem neatly.

The #import directive, like the #include directive (K&R 4.11), can specify a file in angle brackets or in quotation marks:

#import <UIKit/UIKit.h> #import "MyHeader.h"

The quotation marks form means “look for the named file in the same folder as this file” (the .m file in which the #import line occurs). The angle brackets form means to look among the various header search paths supplied in the build settings; these search paths are set for you automatically, and you normally won’t need to modify them. In general, the distinction means that you’ll use angle brackets to refer to a header file owned by the Cocoa API and quotation marks to refer to a header file that you wrote. If you’re curious as to what an #import directive imports, select it (in Xcode) and choose File → Open Quickly to display the contents of the designated header file.

Get Programming iOS 4 now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.