Endpoints

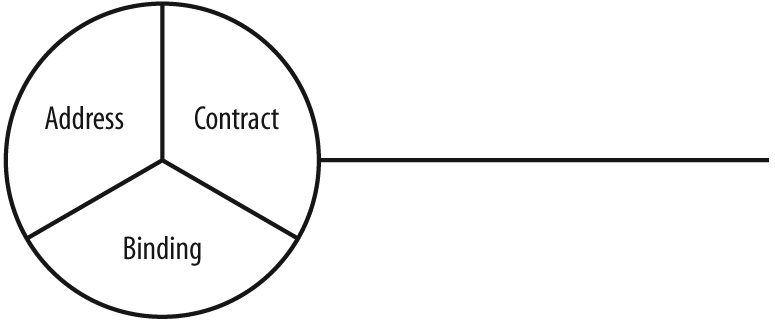

Every service is associated with an address that defines where the service is, a binding that defines how to communicate with the service, and a contract that defines what the service does. This triumvirate governing the service is easy to remember as the ABC of the service. WCF formalizes this relationship in the form of an endpoint. The endpoint is the fusion of the address, contract, and binding (see Figure 1-5).

Figure 1-5. The endpoint

Every endpoint must have all three elements, and the host exposes the endpoint. Logically, the endpoint is the service's interface and is analogous to a CLR or COM interface. Note in Figure 1-5 the use of the traditional "lollipop" notation to denote an endpoint.

Tip

Conceptually, even in C# or VB you have endpoints: the address is the memory address of the type's virtual table, the binding is CLR, and the contract is the interface itself. Because in classic .NET programming you never deal with addresses or bindings, you take them for granted, and you've probably gotten used to equating in your mind's eye the interface (which is merely a programming construct) with all that it takes to interface with an object. The WCF endpoint is a true interface, because it contains all the information required to interface with the object. In WCF, the address and the binding are not preordained and need to be configured.

Every service must expose at least ...