A Short Introduction

To explain ggplot2, we’ll

start by looking at a very simple data set:[47]

> d <- data.frame(a=c(0:9), b=c(1:10), c=c(rep(c("Odd", "Even"), times=5))) > d a b c 1 0 1 Odd 2 1 2 Even 3 2 3 Odd 4 3 4 Even 5 4 5 Odd 6 5 6 Even 7 6 7 Odd 8 7 8 Even 9 8 9 Odd 10 9 10 Even

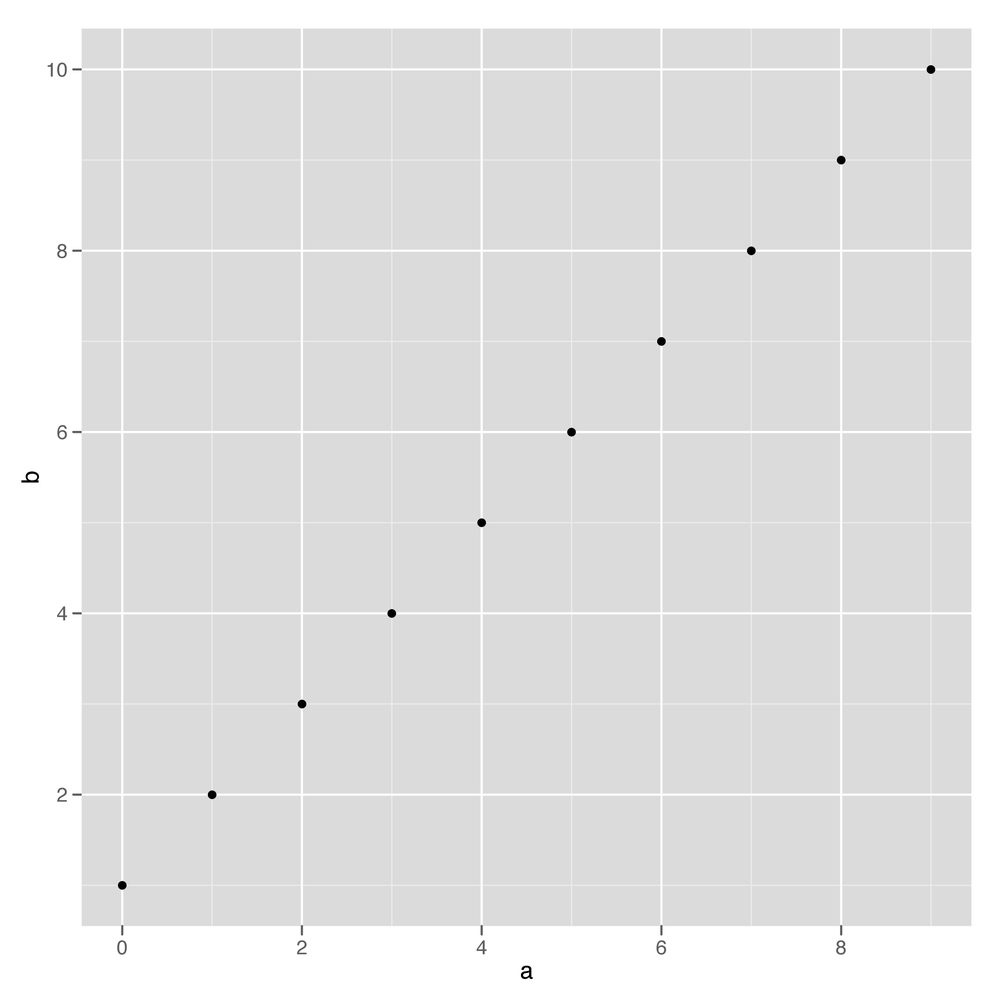

Let’s think about what we want to show. We want to show how variable

y varies with variable x. (To start with, we’ll forget about showing

which points belong in a or b, and just plot points.) We’ll use the

qplot (for “quick plot”) function to

show this relationship. Plotting points is the default for qplot, so we’ll call qplot with the arguments x=a, y=b, and

data=d:

> library(ggplot2) > qplot(x=a, y=b, data=d)

The result is shown in Figure 15-1. Notice

what we specified: a value to plot on an x-axis, a value to plot on a

y-axis, and a data set. We focused on describing the relationship we

wanted to show, not on the type of plot. That’s the key idea of ggplot: you describe what you want to present,

not how to present it.

Figure 15-1. Simplest qplot example

When you create a new plot with ggplot2, you are not actually plotting the data to the screen. Instead, you are creating a new plot object. (This is very similar to how the lattice package works.) When you type a plot command on the console, R will create the object, and then the print method will be called on the object; the print method actually draws ...

Get R in a Nutshell, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.