Chapter 4. Action Controller

Introduction

In the Rails architecture, Action Controller receives incoming requests and hands off each request to a particular action. Action Controller is tightly integrated with Action View; together they form Action Pack.

Action Controllers, or just “controllers,” are classes that inherit from ActionController::Base. These classes define

the application’s business logic. A real estate web application might

have one controller that handles searchable housing listings, and

another controller devoted to administration of the site. In this way,

controllers are grouped according to the data they operate on.

Controllers often correspond to the model that they primarily operate

on, although this doesn’t have to be the case.

A controller is made up of actions, which are the public methods

of a controller class. To process incoming requests, Action Controller

includes a routing module that maps URLs to specific actions. By

default, a request to http://railsurl.com/rental/listing/23

tries to invoke the listing action of

the RentalController controller,

passing in an id of 23. As with much

of the Rails framework, if this behavior doesn’t fit your application’s

requirements, it’s easy to configure something different.

After Action Controller has determined which action should handle the incoming request, the action gets to perform its task: for example, updating the domain model based on the parameters in the request object. When the action has finished, Rails usually attempts to render a view template with the same name as that action. There are several ways this normal process can be altered, though; an action can redirect to other actions, or it can request that a specific view be rendered. Eventually, a template or some form of output is rendered, completing the request cycle.

Understanding that business logic belongs in the controller rather than in the view and that domain logic should be separated into the model, is the key to maximizing the benefits of the MVC design pattern. Follow this pattern, and your applications will be easier to understand, maintain, and extend.

Accessing Form Data from a Controller

Problem

You have a web form that collects data from the user and passes it to a controller. You want to access that data within the controller.

Solution

Use the params hash. Given

the form:

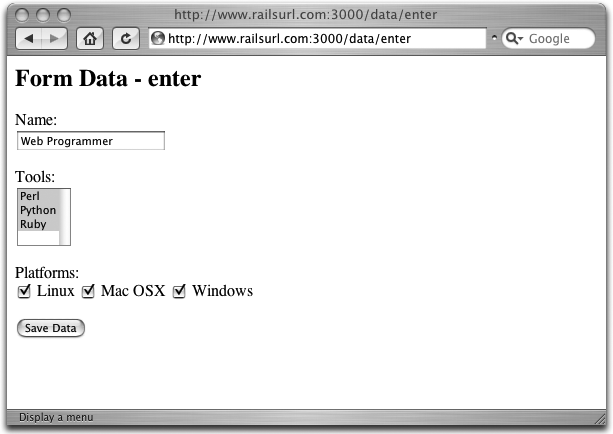

app/views/data/enter.rhtml:

<h2>Form Data - enter</h2>

<% form_tag(:action => "show_data") do %>

<p>Name:

<%= text_field_tag("name","Web Programmer") %></p>

<p>Tools:

<% opts = ["Perl", "Python", "Ruby"].map do |o|

"<option>#{o}</option>"

end.to_s %>

<%= select_tag("tools[]", opts, :multiple => "true") %></p>

<p>Platforms:

<%= check_box_tag("platforms[]","Linux") %> Linux

<%= check_box_tag("platforms[]","Mac OSX") %> Mac OSX

<%= check_box_tag("platforms[]","Windows") %> Windows</p>

<%= submit_tag("Save Data") %>

<% end %>When the form has been submitted, you can access the data using

the params hash within your

controller.

app/controllers/data_controller.rb:

class DataController < ApplicationController

def enter

end

def show_data

@name = params[:name]

@tools = params[:tools] || []

@platforms = params[:platforms] || []

end

endDiscussion

The web server stores the elements of a submitted form in the

request object. These elements are available to your application

through the params hash. The

params hash is unique because you

can access its elements using strings or symbols as keys.

Figure 4-1 shows the form; it has three different types of HTML elements.

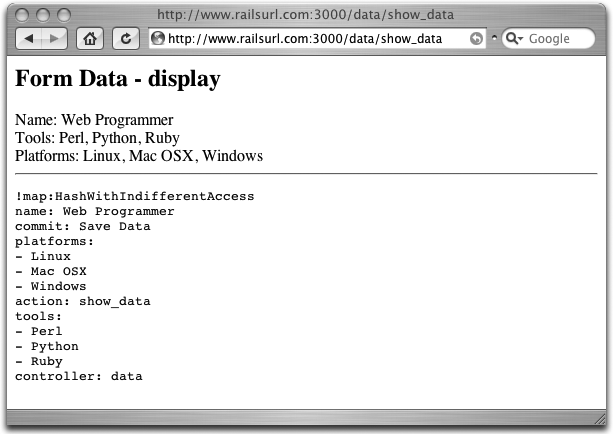

The following view displays the data that the form collects. The

last line is a call to the debug

template helper, which displays the contents of the params hash in yaml format:

app/views/data/show_data.rhtml:

<h2>Form Data - display</h2>

Name: <%= @name %>;

Tools: <%= @tools.join(", ") %>;

Platforms: <%= @platforms.join(", ") %>;

<hr>

<%= debug(params) %>Figure 4-2 shows the rendered view.

To access the name field of

the form, use :name as the key to

the params hash (e.g., params[:name]). The selected elements of the

multiselect list and the checkboxes are stored in the params hash as arrays named after their

associated HTML element names.

For example, if you submit the form in the solution with Python

and Ruby selected for Tools and Mac OS X checked for Platforms, the

params hash contains the following

arrays:

{ "tools"=>["Python", "Ruby"], "platforms"=>["Mac OSX"] }This behavior is triggered by appending [] to the name of an

element that can have more than one value. If no items are selected,

there will be no variable in params

corresponding to that element.

Form data can also be structured as an arbitrarily deeply nested

tree of hashes and arrays within the params hash. Hashes are created by placing the name of the nested

hash between the square brackets at the end of the field name. The

following hidden form fields illustrate a nesting that is up to three

levels deep (i.e., params contains

a student hash, which contains a

scores hash, which contains a

:midterm array with values and

:final key with a value).

<input type="hidden" name="student[scores][midterm][]" value="88"> <input type="hidden" name="student[scores][midterm][]" value="91"> <input type="hidden" name="student[scores][final]" value="95">

If you add these hidden fields to the solution’s form, you get

the following student data

structure params hash:

"student"=> {

"scores"=> {

"final"=>"95",

"midterm"=> [

"88",

"91"

]

}

}Here’s how to access the student’s second midterm scores:

params[:student][:scores][:midterm][1]

Changing an Application’s Default Page

Problem

By default, when a browser requests http://railsurl.com, that request is mapped to public/index.html. Instead, you’d like such requests to call a specific action.

Solution

First, you need to rename or move public/index.html.

Then edit config/routes.rb to map URLs into the appropriate controllers and actions:

config/routes.rb:

ActionController::Routing::Routes.draw do |map| map.connect '', :controller => "customer", :action => "welcome" map.connect ':controller/service.wsdl', :action => 'wsdl' map.connect ':controller/:action/:id' end

Be sure that the line you add is the first call to map.connect in

this file.

Discussion

The routes.rb file is at the heart of the Rails routing system. This file contains rules that try to match the URL path of a request and determine where to direct that request. The rules are tested in the order that they’re defined in the file. The first rule to match a request’s URL path determines the fate of that request.

The rules in routes.rb are calls to

map.connect. The first argument of

map.connect describes how the URL

path must be structured for this rule to be used. The remaining

arguments are key/value pairs that specify how the request is routed

to your application. Once a request matches a rule in this file, all

remaining map.connect rules are

ignored.

So, the rule we added has an initial argument of ''. This says, “Match any request where the

URL path is empty.” The second argument specifies the controller to

use and the third, the action. The entire rule states that requests

with no URL path are to use the welcome action of the BooksController.

Finally, requests with an empty URL are really a special case because Rails directs them to /public/index.html. If that file exists, the rules in routes.rb do nothing; otherwise, the rules are evaluated.

Clarifying Your Code with Named Routes

Problem

You are using link_to

throughout your application to generate URLs programmatically, but you

still find that there’s duplication across these calls for URLs that

you use often. You want a shorthand way to refer to the most common

routes in your application.

Solution

Use named routes.

Discussion

In your application’s config/routes.rb

file, you can create named routes simply by replacing map.connect with map. name, where name can be a descriptive name

for that specific route definition.

Here’s a named route, called admin_report, that routes a request to the

report action of the Admin

controller:

map.admin_report 'report/:year',

:controller => 'admin',

:action => 'report'Having this named route in routes.rb tells

Rails to create two new methods associated with this route: admin_report_url and hash_for_admin_report_url. You use the first

method, admin_report_url, to

reference this route anywhere that Rails requires a URL. The latter

method just returns the routing

hash for that route. With this named route defined, we can now use

admin_report_url in a link_to helper:

<%= link_to "Administrative Report", admin_report_url(:year => 2005) %>

Internally, admin_report_url

is a call to url_for that’s passed

the hash from the route definition. Any additional hash entries can be

passed as arguments to admin_report_url; these entries are merged

with the hash from the route definition, and are dealt with according

to the rules defined by that route. In this example, the year for the

report is passed as an argument to the admin_report_url method.

It’s common to define a named route for the main page of your

application. Here’s how to define such a route called home that takes you to the page managed by

the Main controller:

map.home '', :controller => "main"

You can use this route in a redirect within a controller:

redirect_to home_url

Configuring Customized Routing Behavior

Problem

You need precise control over how Rails maps URLs into controllers actions. By

default, a request to http://railsurl.com/blog/show/5

calls the show action of the Blog

controller with an id of 5 (i.e.,

:controller/:action/:id, which you

can see in the last map.connect line in

config/routes.rb). You want Rails to route URLs

constructed from date information directly to articles. But http://railsurl.com/blog/2005/11/6

requests the 2005 action of the

Blog controller, which makes little sense. How do you map URLs with

dates into meaningful controllers and actions?

Solution

Add the following as the first rule in config/routes.rb:

ActionController::Routing::Routes.draw do |map|map.connect 'blog/:year/:month/:day',:controller => 'blog',:action => 'display_by_date',:month => nil,:day => nil,:requirements => { :year => /\d{4}/,:day => /\d{1,2}/,:month => /\d{1,2}/ }map.connect ':controller/service.wsdl', :action => 'wsdl' map.connect ':controller/:action/:id' end

With display_by_date defined

in the Blog controller:

app/controllers/BlogController.rb:

class BlogController < ApplicationController

def display_by_date

year = params[:year]

month = params[:month]

day = params[:day]

day ='0'+day if day && day.size == 1

@day = day

if ( year && month && day )

render(:template => "blog/#{year}/#{month}/#{day}")

elsif ( year )

render(:template => "blog/#{year}/list")

end

end

endDiscussion

The solution routes a request to http://railsurl.com/blog/2005/11/6

directly to the display_by_date

method of the BlogController. The

display_by_date method receives the

following parameter hash:

params = { :year => 2005,

:day => 6,

:month => 11 }When presented with these values, display_by_date retrieves the blog entry

from November 6, 2005. This method has some additional display

functionality as well, which we’ll get to in a moment.

Here’s how our map.connect

rule works:

The first argument of map.connect is a pattern that describes the

URL path that we’re looking for this rule to match. In this case, when

we see a URL path of the form /blog/2005/6/11, we

create a hash with :year =>

2005, :month => 6, and

:day => 11. (All this really

matches is the /blog///; the stuff between the

last three slashes is added to the hash.) This does nothing to

guarantee that the stuff between the slashes has anything to do with

an actual date; it just matches the pattern and adds key/value pairs

to the hash.

The initial argument does not add :controller or :action keys to our hash. Without a

controller specified, Rails produces a routing error. If we specify

the Blog controller but no action, Rails assumes an action of index or throws an error if no index method is defined. So we’ve added

:controller => 'blog' and

:action => to explicitly

tell Rails to use the 'display_by_date'display_by_date method of the Blog

controller.

The next two arguments in our rule, :month => nil and :day => nil, set a default of nil to the

:month and :day keys of the hash. Keys with nil values

won’t get included in the params

hash passed to display_by_date.

Using nil values lets you specify the year but omit the month and day

components of the URL path. display_by_date interprets the lack of month

and day variables as a special request to display all blog entries for

the specified year.

The last argument assigns a subhash to the :requirements key. This subhash contains

specifics about what we’re willing to accept as a valid date. We use

it to provide regular expressions that tell us whether we’re actually

looking at a year, month, and a day—the value assigned to year must

match /\d(4)/ (i.e., a string of four digits)—and

so on.

See Also

Displaying Alert Messages with Flash

Problem

You’ve created an informative message while processing the current request. You want this message to be available for display during the next request. Additionally, the message should cease to be available following the next request.

Solution

You have a form that requests the user to enter a password that meets a certain criteria.

views/password/form.rhtml:

<h2>Please choose a good password:</h2> <p style="color: red;"><%= flash[:notice] %></p> <% form_tag(:action => 'check') do %> <input type="text" name="pass"> <input type="submit"> <p>(8 character minimum, at least 2 digits)</p> <% end %>

The form submits to the Check controller, which strips the password candidate of all whitespace, and then a couple of regular expressions test that the password meets the criteria. The tests are broken up to provide more specific error message notifications.

If both matches succeed, the request is redirected to the

success action and passed along to

:pass for display. If either check

fails, the request redirects back to the form action.

app/controllers/password_controller.rb:

class PasswordController < ApplicationController

def form

end

def check

password = params['pass'].strip.gsub(/ /,'')

if password =~ /\w{8}/

flash[:notice] = "Your password is long enough"

if password =~ /\d+.*\d+/

flash[:notice] += " and contains enough digits."

redirect_to :action => 'success', :pass => password

return

else

flash[:notice] = "Sorry, not enough digits."

end

else

flash[:notice] = "Sorry, not long enough."

end

redirect_to :action => 'form'

end

def success

@pass = params['pass']

end

endUpon success, the user is redirected to success.rthml

, and his password is displayed (without any whitespace it

may have contained):

views/password/success.rthml:

<h2>Success!</h2> <% if flash[:notice] %> <p style="color: green;"><%= flash[:notice] %></p> <% end %>

Discussion

Building a usable web application hinges on keeping the user

informed about what’s going on, and why things happen. Communicative

alert messages are an integral part of most good applications.

Displaying such messages is so common that Rails has a facility for

doing so called the flash.

Internally, the flash is just

a hash stored in the session object. It has the special quality of

getting cleared out after the very next request (though you can alter

this behavior with the flash.keep

method).

Redirecting with redirect_to

is often used to display a new URL in the location bar of the browser,

somewhat hiding the inner workings of an application. Because messages

stored in the flash are just stored

in the session object, they are available across such redirects,

unlike instance variables. And since they last only for one more

request, hitting the refresh button makes the message disappear. From

the user’s perspective, this is usually the ideal behavior.

If you find yourself tempted to use the flash to store more than just user

notification messages (e.g., object IDs), make sure to consider

whether using the standard session object would work as well or

better.

Extending the Life of a Flash Message

Problem

You’ve created a flash message and are displaying it to the user. You’d like to extend the life of that message for one more request than would normally exist.

Solution

You can call the keep method

of the Flash class on a specific entry, or the entire contents of the

flash hash. This technique is

useful for redisplaying flash messages in subsequent requests without

explicitly recreating them.

To demonstrate this, create the following Rental Controller:

app/controllers/rental_controller.rb:

class RentalController < ApplicationController

def step_one

flash.now[:reminder] = 'There is a $20 fee for late payments.'

flash.keep(:reminder)

end

def step_two

end

def step_three

end

endAnd create the following three views:

app/views/rental/step_one.rhtml:

<h1>Step one!</h1> <% if flash[:reminder] %> <p style="color: green;"><%= flash[:reminder] %></p> <% end %> <a href="step_two">step_two</a>

app/views/rental/step_two.rhtml:

<h1>Step two!</h1> <% if flash[:reminder] %> <p style="color: green;"><%= flash[:reminder] %></p> <% end %> <a href="step_three">step_tree</a>

app/views/rental/step_three.rhtml:

<h1>Step three!</h1> <% if flash[:reminder] %> <p style="color: green;"><%= flash[:reminder] %></p> <% end %> <a href="step_one">step_one</a>

Discussion

As you can see in the solution, the controller creates a flash message only in the action called step_one.

From a browser, in the first step you see the reminder on the screen. When you click on the link at the bottom of the page, you call step_two. Now the flash message is shown a second time.

Step three is like step two, but we didn’t call the flash.keep in this method, and the message

doesn’t reappear. The keep method

holds the reminder for only one request.

See Also

Following Actions with Redirects

Problem

Submitting a form in your application calls an action that updates your model. You want this action to redirect to a second action that will handle rendering. This way, when the response is sent, the user will see a new URL; refreshing the page will not re-initiate the first action.

Solution

Call redirect_to, as in the

following controller’s new

action:

app/controllers/password_controller.rb:

class AccountController < ApplicationController

def list

end

def new

@account = Account.new(params[:account])

if @account.save

flash[:notice] = 'Account was successfully created.'

redirect_to :action => 'list'

end

end

endDiscussion

The solution defines a new

method that attempts to create a new account. If a newly created

account is saved successfully, the new method stores a flash notice and calls

redirect_to to redirect to the

controller’s list action.

redirect_to takes an options hash as an argument. Internally,

this hash is passed to url_for to

create a URL. If it’s passed a string that begins with protocol

information (e.g., http://), it

uses the string as the entire relocation target. Otherwise, it

interprets the string as a relative URI. Finally, redirect_to can be passed the symbol

:back, which tells the browser to

redirect to the referring URL or the contents of

request.env["HTTP_REFERER"].

Redirection works by sending the browser an HTTP/1.1 302 Found status code, telling the browser

that “the requested resource resides temporarily under a different

URI,” or simply that it should redirect to the URI supplied in this

response. This prevents users from creating duplicate accounts with

their refresh button, because refreshing only reloads the list

template.

A common question on the rubyonrails

mailing list is when to use render,

instead of redirect_to. As this

solution demonstrates, if you don’t want a refresh to re-initiate an

action that makes changes to your model, use redirect_to. If you want a search form URL,

such as /books/search, to remain the same, even

when results of the search are displayed by a new action, use render. (When running in development mode,

renders are faster than redirects because they don’t reload the

environment.)

See Also

Generating URLs Dynamically

Problem

There are many places in your code where you supply URLs to Rails methods that link to other parts of your application. You don’t want to lose the flexibility Rails’ Routes provide by hardcoding URL strings throughout your application, especially if you decide to change how routing works later. You want to generate URLs within your application based on the same rules that Routes uses to translate URL requests.

Discussion

Let’s say your default route (as defined in config/routes.rb) is as follows:

map.connect ':controller/:action/:id'

Then a call to url_for, such

as:

url_for :controller => "gallery", :action => "view", :id => 4

produces the URL http://railsurl.com/gallery/view/4,

which is handled by the default route. If you don’t specify the

controller, url_for assumes you

want the current controller (the controller to which Rails delegated

the current HTTP request).

This default behavior is useful because you’re often calling

url_for to create a URL for another

action in the current controller.

The same default behavior applies to the action and the ID: if

you do not specify new ones, url_for defaults to the current one. Thus,

for any of the components of the URL that you don’t explicitly

specify, Rails attempts to use values from the current request to

construct a possible route mapping.

As soon as url_for finds one

component that is different from the current request, it essentially

slashes off all components to the right of it in the URL and no longer

uses them as defaults. So, if you specify a different controller that

of the current request, then neither the action nor any of the other

parts of the current URL will be used to construct the new URL.

If the specified controller name begins with a slash, no

defaults are used. If the controller changes, the action defaults to

'index' unless you specify a new

one.

How the defaults work can get a little complicated, but url_for is usually intuitive. If you’re

having trouble with unpredictable defaults, you can render the

generated URL with render_text

temporarily:

render_text url_for :controller => "gallery", :action => "view", :id => 4

If you want to replace certain parts of the current URL without

affecting any of the other parts of it, use the :overwrite_params option. For instance, if

you want to change the current action to 'print', but keep the controller and the ID

the same, use:

url_for :overwrite_params => { :action => 'print' }This takes the current URL, replaces only the :action, and returns it as the new

URL.

Inspecting Requests with Filters

Problem

You have taken over development of a Rails application, and you are trying to figure out how it processes requests. To do so, you want to install a logging mechanism that will let you inspect the request cycle in real time.

Solution

Use an after_filter

to invoke a custom logging method for each request.

Define a CustomLoggerFilter

class:

app/controllers/custom_logger_filter.rb:

require 'logger'

require 'pp'

require 'stringio'

class CustomLoggerFilter

def self.filter(controller)

log = Logger.new('/var/log/custom.log')

log.warn("params: "+controller.params.print_pretty)

end

end

class Object

def print_pretty

str = StringIO.new

PP.pp(self,str)

return str.string.chop

end

endInstall the logger in the AccountsController by passing it as an

argument in a call to after_filter:

app/controllers/accounts_controller.rb:

class AccountsController < ApplicationController

after_filter CustomLoggerFilter

def index

list

render :action => 'list'

end

def list

@account_pages, @accounts = paginate :accounts, :per_page => 10

end

def show

@account = Account.find(params[:id])

end

def new

@account = Account.new

end

def create

@account = Account.new(params[:account])

if @account.save

flash[:notice] = 'Account was successfully created.'

redirect_to :action => 'list'

else

render :action => 'new'

end

end

def edit

@account = Account.find(params[:id])

end

def update

@account = Account.find(params[:id])

if @account.update_attributes(params[:account])

flash[:notice] = 'Account was successfully updated.'

redirect_to :action => 'show', :id => @account

else

render :action => 'edit'

end

end

def destroy

Account.find(params[:id]).destroy

redirect_to :action => 'list'

end

endDiscussion

Rails filters allow you to do additional processing before or

after controller actions. In the solution, we’ve implemented a custom

logging class that is invoked after calls to any actions in the

Accounts controller. Our logger opens a filehandle and prints a

formatted version of the params

hash for easy inspection.

With the logger in place, you can use the Unix tail command to

watch the logfile as it grows. You’ll see what happens to the params hash with every action that’s

called:

tail -f /var/log/custom.log

For the AccountsController in

the solution, you can watch the log as you list, create, and destroy

accounts.

params: {"action"=>"list", "controller"=>"accounts"}

params: {"action"=>"new", "controller"=>"accounts"}

params: {"commit"=>"Create",

"account"=>{"balance"=>"100.0", "first_name"=>"John", "last_name"=>"Smythe"},

"action"=>"create",

"controller"=>"accounts"}

params: {"action"=>"list", "controller"=>"accounts"}

params: {"action"=>"destroy", "id"=>"2", "controller"=>"accounts"}

params: {"action"=>"list", "controller"=>"accounts"}Rails comes with a number of built-in logging facilities. This approach gives you an easy way to add logging to a controller with only one line of code. You can also limit what actions of the controller the filter is applied to.

See Also

Logging with Filters

Problem

You have an application for which you would like to log more information than you get from the standard Rails logging facilities.

Solution

Use the around_filter to

record the times before and after each action is invoked, and log that

information in your database.

First, create a database table to store the custom logging;

we’ll call that table action_logs.

Here’s a migration to create it:

db/migrate/001_create_action_logs.rb:

class CreateActionLogs < ActiveRecord::Migration

def self.up

create_table :action_logs do |t|

t.column :action, :string

t.column :start_time, :datetime

t.column :end_time, :datetime

t.column :total, :float

end

end

def self.down

drop_table :action_logs

end

endThen create the class named CustomLogger. This class must have before and after methods, which are called before and

after each action of the controller that you’re logging. The before method records the initial time; the

after method records the time after

the action has completed, and stores the initial time, the final time,

the elapsed time, and the name of the action in the action_logs table.

app/controllers/custom_logger.rb:

class CustomLogger

def before(controller)

@start = Time.now

end

def after(controller)

log = ActionLog.new

log.start_time = @start

log.end_time = Time.now

log.total = log.end_time.to_f - @start.to_f

log.action = controller.action_name

log.save

end

endNext, apply the filter to the actions. Add the following line to the beginning of your controller:

around_filter CustomLogger.new

Now, when you use your site, you’ll be logging data to the

action_logs table in your database.

Each log entry (start, finished, and elapsed times) is associated with

the name of the method that was executing:

mysql> select * from action_logs; +----+-------------+---------------------+---------------------+-----------+ | id | action | start_time | end_time | total | +----+-------------+---------------------+---------------------+-----------+ | 1 | index | 2006-01-12 00:47:52 | 2006-01-12 00:47:52 | 0.011997 | | 2 | update_each | 2006-01-12 00:47:52 | 2006-01-12 00:47:54 | 1.75978 | | 3 | update_all | 2006-01-12 00:47:54 | 2006-01-12 00:47:54 | 0.0353839 | | 4 | reverse | 2006-01-12 00:47:55 | 2006-01-12 00:47:55 | 0.0259092 | | 5 | show_names | 2006-01-12 00:47:55 | 2006-01-12 00:47:55 | 0.0264592 | +----+-------------+---------------------+---------------------+-----------+ 5 rows in set (0.00 sec)

You can see that the controller is spending a lot of its time in

the update_each method; that method

is therefore a target for optimization.

Of course, you can do much better than this; you can write a Rails application to display the results or write some other application to analyze the data.

Discussion

around_filter requires that

the object passed to it as an argument implement a before and an after method. The CustomLogger class records the current time

in its before method. The after method creates a new ActionLog object and records the start and

end times as well as the difference between the two. The other filters

in Rails allow you to include or exclude the actions of the controller

that they apply to. The around_filter

doesn’t allow for such granularity and operates on all

actions invoked by each request.

To be more specific about what actions the around_filter is applied to, wrap your code

so that it executes only when the action matches a particular pattern.

Doing this is simple, because the controller.action_name property tells you

what action is being called. The following version of the after method shows how you can log only

those actions whose names begin with the string update. If the action name doesn’t match

this string, after just terminates,

without recording any data:

def after(controller)

if controller.action_name =~ /^update/

log = ActionLog.new

log.start_time = @start

log.end_time = Time.now

log.total = log.end_time.to_f - @start.to_f

log.action = controller.action_name

log.save

end

endRendering Actions

Problem

You have an action that has gathered some data from your model, perhaps based on a user-defined query, and you want to render another action to display the results.

Solution

Use render :action =>

'action_name', where action_name is the name of the action that

displays the result. The search

method in CategoriesController does

just that:

app/controllers/categories_controller.rb:

class CategoriesController < ApplicationController

def search_form

end

def search

@categories = Category.find(:all,

:conditions =>

["name like ?", "%#{params[:cat]}%"])

if @categories

render :action => 'search_results'

else

flash['notice'] = 'No Category found.'

render :action => 'search_form'

end

end

def search_results

@category = Category.find(params[:id])

end

endDiscussion

In the solution, if the find

call in search action successfully

returns a category, the search_results

action is rendered. At that point, Rails looks for a template file

named after that action, under a directory named after the controller,

i.e.,

app/views/categories/search_results.rhtml.

This is probably the most common pattern of control flow in Rails: you perform a query, or some other immutable action, and then you display the results of that action with a second action. Ideally, these actions are separate because they do distinctly different tasks (the first allows the user to make a query; the second displays the results), and combining the two actions into a single method inhibits code reuse.

The solution calls render only once,

whether or not a category is found in the database. It’s possible to

render an action that renders another action, and so on, but you’ll

get a DoubleRenderError if you try

to render twice within the same action. Rails 0.13 added this error

message to help avoid confusing side effects of parallel render

attempts.

An action can continue processing after a call to render, but it usually makes more sense to

call render at the end of the

action (just before the return

statement, if there is one). This way, the rendered action can

communicate success or failure to the user.

Rails renders actions within the layout that is associated with

the action’s controller. You can optionally render with no layout by

specifying :layout=>false:

render :action => "display", :layout => false

Or you can specify another layout by supplying the name of that layout:

render :action => "display", :layout => "another_layout"

See Also

Restricting Access to Controller Methods

Problem

By default, all public methods in your controller can be

accessed via a URL. You have a method in your controller that is used

by other methods in that controller or by subclasses of that

controller. For security reasons, you would like to prevent public

requests from accessing that method.

Solution

Use Ruby’s private or protected methods

to restrict public access to controller methods that should not be

accessible from outside the class:

app/controllers/controllers/employee_controller.rb:

class EmployeeController < ApplicationController

def add_accolade

@employee = Employee.find(params[:id])

@employee.accolade += 1

double_bonus if @employee.accolade > 5

end

private

def double_bonus

@employee.bonus *= 2

end

endDiscussion

Ruby has three levels of class method access control. They are

specified with the following methods: public, private, and protected. Public methods can be called by

any other object or class. Protected methods can be invoked by other

objects of the same class and its subclasses, but not objects of other

classes. Private methods can be invoked only by an object on

itself.

By default, all class methods are public unless otherwise specified. Rails defines actions as public methods of a controller class. So by default, all of a controller’s class methods are actions and available via publicly routed requests.

The solution shows a situation in which you might not want all

class methods publicly accessible. The double_bonus method is defined after a call

to the private method, making the

method unavailable to other classes. Therefore, double_bonus is no longer an action and is

available only to other methods in the Employee controller or its

subclasses. As a result, a web application user can’t create a URL

that directly invokes double_bonus.

Likewise, to make some of your class’s methods protected, call

the protected method before

defining them. private and protected (and, for that matter, public) remain in effect until the end of

the class definition, or until you call one of the other access

modifiers.

Sending Files or Data Streams to the Browser

Problem

You want to send e-book contents directly from your database to the browser as text and give the user the option to download a compressed version of each book.

Solution

You have a table that stores plain text e-books:

db/schema.rb:

ActiveRecord::Schema.define(:version => 3) do

create_table "ebooks", :force => true do |t|

t.column "title", :string

t.column "text", :text

end

endIn the Document Controller, define a view that calls

send_data if the :download parameter is present, and render if it is not:

app/controllers/document_controller.rb:

require 'zlib'

require 'stringio'

class DocumentController < ApplicationController

def view

@document = Ebook.find(params[:id])

if (params[:download])

send_data compress(@document.text),

:content_type => "application/x-gzip",

:filename => @document.title.gsub(' ','_') + ".gz"

else

render :text => @document.text

end

end

protected

def compress(text)

gz = Zlib::GzipWriter.new(out = StringIO.new)

gz.write(text)

gz.close

return out.string

end

endDiscussion

If the view action of the

Document Controller is invoked with the URL http://railsurl.com/document/view/1,

the e-book with an ID of 1 is rendered to the browser as plain

text.

Adding the download parameter

to the URL, which yields http://railsurl.com/document/view/1?download=1,

requests that the contents of the e-book be compressed and sent to the

browser as a binary file. The browser should download it, rather than

trying to render it.

There are several different ways to render output in Rails. The most common are action renderers that process ERb templates, but it’s also customary to send binary image data to the browser.

Storing Session Information in a Database

Problem

By default, Rails uses Ruby’s PStore mechanism to maintain session information in the filesystem. However, your application may run across several web servers, complicating the use of a centralized filesystem-based solution. You want to change the default store from the filesystem to your database.

Solution

In environment.rb, update the session_store option by making sure it’s set

to :active_record_store and that

the line is uncommented:

config/environment.rb:

Rails::Initializer.run do |config| # Settings in config/environments/* take precedence to those specified here config.action_controller.session_store = :active_record_store end

Run the following rake command to

create the session storage table in your database:

~/current$ rake create_sessions_table

Restart your web server for the changes to take effect.

Discussion

Rails offers several options for session data storage, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. The available options include: FileStore, MemoryStore, PStore (the Rails default), DRbStore, MemCacheStore, and ActiveRecordStore. The best solution for your application depends heavily on the amount of traffic you expect and your available resources. Benchmarking will ultimately tell you which option provides the best performance for your application. It’s up to you to decide if the fastest solution (usually in-memory storage) is worth the resources that it requires.

The solution uses ActiveRecordStore, which is enabled in the Rails environment configuration

file. rake’s create_sessions_table

task creates the database table that Rails needs to store the session details.

If you’d like to reinitialize the session table, you can drop the current one with:

rake drop_sessions_table

Then recreate the table it with the rake command, and restart your web

server.

The session table that rake

creates looks like this:

mysql> desc sessions; +------------+--------------+------+-----+---------+----------------+ | Field | Type | Null | Key | Default | Extra | +------------+--------------+------+-----+---------+----------------+ | id | int(11) | | PRI | NULL | auto_increment | | session_id | varchar(255) | YES | MUL | NULL | | | data | text | YES | | NULL | | | updated_at | datetime | YES | | NULL | | +------------+--------------+------+-----+---------+----------------+ 4 rows in set (0.02 sec)

The following line fetches an Active Record User object and stores it in the session hash.

session['user'] = User.find_by_username_and_password('rorsini','elvinj')You can use the debug helper function <%=debug(session) %> to view session

output. A dump of the session hash

shows the contents of the current session. Here’s a fragment of the

dump, showing the User

object:

!ruby/object:CGI::Session

data: &id001

user: !ruby/object:User

attributes:

username: rorsini

id: "1"

first_name: Rob

password: elvinj

last_name: OrsiniThe same session record can be viewed directly in the sessions table, but the serialized data will

be unreadable. The updated_at field

can be helpful if you find the sessions table getting large. You can use

that date field to remove sessions that are more than a certain age

and thus no longer valid.

mysql> select * from sessions\G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

id: 1

session_id: f61da28de115cf7f19c1d96beed4b960

data: BAh7ByIJdXNlcm86CVVzZXIGOhBAYXR0cmlidXRlc3sKIg11c2VybmFtZSIM

cm9yc2luaSIHaWQiBjEiD2ZpcnN0X25hbWUiCFJvYiINcGFzc3dvcmQiC2Vs

dmluaiIObGFzdF9uYW1lIgtPcnNpbmkiCmZsYXNoSUM6J0FjdGlvbkNvbnRy

b2xsZXI6OkZsYXNoOjpGbGFzaEhhc2h7AAY6CkB1c2VkewA=

updated_at: 2006-01-04 22:33:58

1 row in set (0.00 sec)See Also

Tracking Information with Sessions

Problem

You want to maintain state across several web pages of an application without using a database.

Solution

Use Rails’s built-in sessions to maintain state across multiple pages of a web application, such as the state of an online quiz.

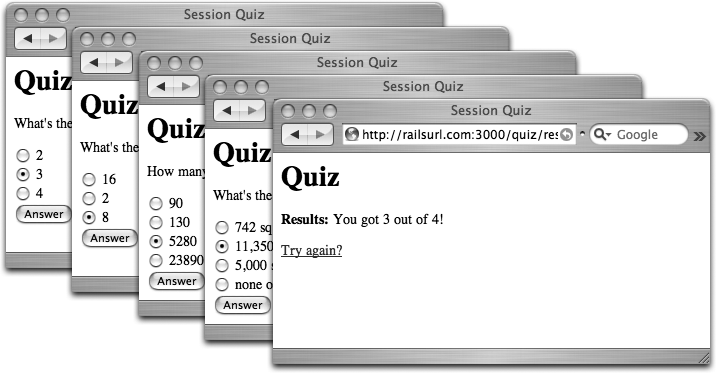

Create an online quiz that consists of a sequence of questions, one per page. As a user proceeds through the quiz, her score is added to the total. The last screen of the quiz displays the results as the number correct out of the total number of questions.

Create a Quiz Controller that includes a data structure to

store the questions, optional answers, and correct answers for each

question. The controller contains methods for displaying each

question, checking answers, displaying the results, and starting

over.

app/controllers/quiz_controller.rb:

class QuizController < ApplicationController

@@quiz = [

{ :question => "What's the square root of 9?",

:options => ['2','3','4'],

:answer => "3" },

{ :question => "What's the square root of 4?",

:options => ['16','2','8'],

:answer => '16' },

{ :question => "How many feet in a mile?",

:options => ['90','130','5,280','23,890'],

:answer => '5,280' },

{ :question => "What's the total area of irrigated land in Nepal?",

:options => ['742 sq km','11,350 sq km','5,000 sq km',

'none of the above'],

:answer => '11,350 sq km' },

]

def index

if session[:count].nil?

session[:count] = 0

end

@step = @@quiz[session[:count]]

end

def check

session[:correct] ||= 0

if params[:answer] == @@quiz[session[:count]][:answer]

session[:correct] += 1

end

session[:count] += 1

@step = @@quiz[session[:count]]

if @step.nil?

redirect_to :action => "results"

else

redirect_to :action => "index"

end

end

def results

@correct = session[:correct]

@possible = @@quiz.length

end

def start_over

reset_session

redirect_to :action => "index"

end

endCreate a template to display each question along with its optional answers:

app/views/quiz/index.rhtml:

<h1>Quiz</h1>

<p><%= @step[:question] %></p>

<% form_tag :action => "check" do %>

<% for answer in @step[:options] %>

<%= radio_button_tag("answer", answer, checked = false) %>

<%= answer %>;

<% end %>

<%= submit_tag "Answer" %>

<% end %>At the end of the quiz, the following view displays the total score along with a link prompting to try again:

app/views/quiz/results.rhtml:

<h1>Quiz</h1> <p><strong>Results:</strong> You got <%= @correct %> out of <%= @possible %>!</p> <%= link_to "Try again?", :action => "start_over" %>

Discussion

The Web is stateless, which means that each request from a browser carries all the information that the server needs to make the request. The server never says, “Oh, yes, I remember that your current score is 4 out of 5.” Being stateless makes it much easier to write web servers but harder to write complex applications, which often need to remember what went before: they need to remember which questions you’ve answered, what items you’ve put in your shopping cart, and so on.

This problem is solved by the use of sessions. A session stores a unique key as a cookie in the user’s browser. The browser presents the session key to the server, which can use the key to look up any state that it has stored as part of the session. The Web interaction is stateless: the HTTP request includes all the information needed to complete the request. But that information contains information the server can use to look up information about previous requests.

In the case of the quiz, the controller checks the answers to

each question and maintains a running total, storing it in the

session hash with the :correct key. Another key in the session hash is used to keep track of the

current question. This number is used to access questions in the

@@quiz class variable, which stores

each question, its possible answers, and the correct answer in an

array. Each question element consists of a hash containing all the

information needed to display that question in the view.

The index view displays a form for each question and submits the

user’s input to the check action of

the controller. Using session[:count], the check action verifies the answer and

increments session[:correct] if

it’s correct. Either way, the question count is incremented, and the

next question is rendered.

When the question count fails to retrieve an element—or

question—from the @@quiz array, the

quiz is over, and the results view is rendered. The total correct is

pulled from the session hash and

displayed with the total number of questions, which is determined from

the length of the quiz array.

A quiz such as this lends itself reasonably well to the convenience of session storage. Be aware that sessions are considered somewhat volatile and potentially insecure, and are usually not used to store critical or sensitive information. For that type of data, a traditional database approach makes more sense.

Figure 4-3 shows the four steps of the session-driven online quiz.

Rails session support is on by default. As the solution

demonstrates, you can access the session hash as if it’s just another

instance variable. If your application doesn’t need session support,

you can turn it off for a controller by using the :disabled option of Action Controller’s

session method in the controller’s

definition. The call to disable session support for a controller may

also include or exclude specific actions within a controller by

passing a list of actions to session’s :only or :except options. The following disables

session support for the display

action of the News Controller:

class NewsController < ActionController::Base session :off, :only => "display" end

To turn session support off for your entire application, pass

:off to the session method within your ApplicationController definition:

class ApplicationController < ActionController::Base session :off end

Using Filters for Authentication

Problem

You want to authenticate users before they’re allowed to use certain areas of your application; you wish to redirect unauthenticated users to a login page. Furthermore, you want to remember the page that the user requested and, if authentication succeeds, redirect them to that page once they’ve authenticated. Finally, once a user has logged in, you want to remember his credentials and let him move around the site without having to re-authenticate.

Solution

Implement an authentication system, and apply it to selected

controller actions using before_filter.

First, create a user database to store user account information and login credentials. Always store passwords as hashed strings in your database, in case your server is compromised.

db/migrate/001_create_users.rb:

class CreateUsers < ActiveRecord::Migration

def self.up

create_table :users do |t|

t.column :first_name, :string

t.column :last_name, :string

t.column :username, :string

t.column :hashed_password, :string

end

User.create :first_name => 'Rob',

:last_name => 'Orisni',

:username => 'rorsini',

:hashed_password =>

'5baa61e4c9b93f3f0682250b6cf8331b7ee68fd8'

end

def self.down

drop_table :users

end

endIn your ApplicationController, define an authenticate method that checks if a user is

logged in and stores the URL of the page the user initially

requested:

app/controllers/application.rb:

# Filters added to this controller will be run for all controllers in the

# application.

# Likewise, all the methods added will be available for all controllers.

class ApplicationController < ActionController::Base

def authenticate

if session['user'].nil?

session['initial_uri'] = request.request_uri

redirect_to :controller => "users", :action => "login"

end

end

endTo make sure the authenticate

method is invoked, pass the symbol :authenticate to before_filter in each controller that gives

access to pages requiring authentication. Here’s how to make sure that

users are authenticated before they can access anything governed by

the ArticlesController or the

BooksController:

app/controllers/articles_controller.rb:

class ArticlesController < ApplicationController before_filter :authenticate def admin end end

app/controllers/books_controller.rb:

class BooksController < ApplicationController before_filter :authenticate def admin end end

Now, create a login form template to collect user credentials:

app/views/users/login.rhtml:

<% if flash['notice'] %> <p style="color: red;"><%= flash['notice'] %></p> <% end %> <% form_tag :action => 'verify' do %> <p><label for="user_username">Username</label>; <%= text_field 'user', 'username' %></p> <p><label for="user_hashed_password">Password</label>; <%= password_field 'user', 'hashed_password' %></p> <%= submit_tag "Login" %> <% end %>

The User sController defines login, verify, and logout methods to handle the authentication

of new users:

app/controllers/users_controller.rb:

class UsersController < ApplicationController

def login

end

def verify

hash_pass = Digest::SHA1.hexdigest(params[:user][:hashed_password])[0..39]

user = User.find(:first,:conditions =>

["username = ? and hashed_password = ?",

params[:user][:username], hash_pass ])

if user

session['user'] = user

redirect_to session['initial_uri']

else

flash['notice'] = "Bad username/password!"

redirect_to :controller => "users", :action => "login"

end

end

def logout

reset_session

# Redirect users to Books#admin, which in turn sends them to

# Users#login, with a refering url of Books#admin:

redirect_to :controller => "books", :action => "admin"

end

endNext, provide a mechanism for users to log themselves out if

they’re not comfortable letting their session time out on its own.

Create a "logout" link with a named

route using logout_url:

app/views/articles/admin.rhtml:

<h1>Articles Admin</h1> <%= link_to "logout", :logout_url %>

app/views/books/admin.rhtml:

<h1>Books Admin</h1> <%= link_to "logout", :logout_url %>

Finally, define the "logout

" named route with its URL

mapping:

config/routes.rb:

ActionController::Routing::Routes.draw do |map| map.logout '/logout', :controller => "users", :action => "logout" # Install the default route as the lowest priority. map.connect ':controller/:action/:id' end

Discussion

Adding authentication to a site is one of the most common tasks in web development. Almost any site that does anything meaningful requires some level of security, or at least a way to differentiate between site visitors.

The Rails before_filter lends

itself perfectly to the task of access control by invoking an authentication method just before controller

actions are executed. Code that is declared as a filter with before_filter has access to all the same

objects as the controller, including the request and response objects,

and the params and session hashes.

The solution places the authenticate filter in the Book and Article

controllers. Every request to either controller first executes the

code in authenticate. This code

checks for the existence of a user

object in the session hash, under

the key of user. If that session key is empty, the URL of the request

is stored in its own session key, and the request is redirected to the

login method of the User

controller.

The login form submits the username and password to the Login controller, which looks for a match in the database. If a user is found with that username and a matching hashed password, the request is redirected to the URL that was stored in the session earlier.

When the user wishes to log out, the logout action of the User controller calls

reset_session, clearing out all the

objects stored in the session. The user is then redirected to the

login screen.

Get Rails Cookbook now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.