Chapter 1. Streaming 101

Streaming data processing is a big deal in big data these days, and for good reasons; among them are the following:

-

Businesses crave ever-more timely insights into their data, and switching to streaming is a good way to achieve lower latency

-

The massive, unbounded datasets that are increasingly common in modern business are more easily tamed using a system designed for such never-ending volumes of data.

-

Processing data as they arrive spreads workloads out more evenly over time, yielding more consistent and predictable consumption of resources.

Despite this business-driven surge of interest in streaming, streaming systems long remained relatively immature compared to their batch brethren. It’s only recently that the tide has swung conclusively in the other direction. In my more bumptious moments, I hope that might be in small part due to the solid dose of goading I originally served up in my “Streaming 101” and “Streaming 102” blog posts (on which the first few chapters of this book are rather obviously based). But in reality, there’s also just a lot of industry interest in seeing streaming systems mature and a lot of smart and active folks out there who enjoy building them.

Even though the battle for general streaming advocacy has been, in my opinion, effectively won, I’m still going to present my original arguments from “Streaming 101” more or less unaltered. For one, they’re still very applicable today, even if much of industry has begun to heed the battle cry. And for two, there are a lot of folks out there who still haven’t gotten the memo; this book is an extended attempt at getting these points across.

To begin, I cover some important background information that will help frame the rest of the topics I want to discuss. I do this in three specific sections:

- Terminology

-

To talk precisely about complex topics requires precise definitions of terms. For some terms that have overloaded interpretations in current use, I’ll try to nail down exactly what I mean when I say them.

- Capabilities

-

I remark on the oft-perceived shortcomings of streaming systems. I also propose the frame of mind that I believe data processing system builders need to adopt in order to address the needs of modern data consumers going forward.

- Time domains

-

I introduce the two primary domains of time that are relevant in data processing, show how they relate, and point out some of the difficulties these two domains impose.

Terminology: What Is Streaming?

Before going any further, I’d like to get one thing out of the way: what is streaming? The term streaming is used today to mean a variety of different things (and for simplicity I’ve been using it somewhat loosely up until now), which can lead to misunderstandings about what streaming really is or what streaming systems are actually capable of. As a result, I would prefer to define the term somewhat precisely.

The crux of the problem is that many things that ought to be described by what they are (unbounded data processing, approximate results, etc.), have come to be described colloquially by how they historically have been accomplished (i.e., via streaming execution engines). This lack of precision in terminology clouds what streaming really means, and in some cases it burdens streaming systems themselves with the implication that their capabilities are limited to characteristics historically described as “streaming,” such as approximate or speculative results.

Given that well-designed streaming systems are just as capable (technically more so) of producing correct, consistent, repeatable results as any existing batch engine, I prefer to isolate the term “streaming” to a very specific meaning:

- Streaming system

-

A type of data processing engine that is designed with infinite datasets in mind.1

If I want to talk about low-latency, approximate, or speculative results, I use those specific words rather than imprecisely calling them “streaming.”

Precise terms are also useful when discussing the different types of data one might encounter. From my perspective, there are two important (and orthogonal) dimensions that define the shape of a given dataset: cardinality and constitution.

The cardinality of a dataset dictates its size, with the most salient aspect of cardinality being whether a given dataset is finite or infinite. Here are the two terms I prefer to use for describing the coarse cardinality in a dataset:

Cardinality is important because the unbounded nature of infinite datasets imposes additional burdens on data processing frameworks that consume them. More on this in the next section.

The constitution of a dataset, on the other hand, dictates its physical manifestation. As a result, the constitution defines the ways one can interact with the data in question. We won’t get around to deeply examining constitutions until Chapter 6, but to give you a brief sense of things, there are two primary constitutions of importance:

- Table

-

A holistic view of a dataset at a specific point in time. SQL systems have traditionally dealt in tables.

- Stream2

-

An element-by-element view of the evolution of a dataset over time. The MapReduce lineage of data processing systems have traditionally dealt in streams.

We look quite deeply at the relationship between streams and tables in Chapters 6, 8, and 9, and in Chapter 8 we also learn about the unifying underlying concept of time-varying relations that ties them together. But until then, we deal primarily in streams because that’s the constitution pipeline developers directly interact with in most data processing systems today (both batch and streaming). It’s also the constitution that most naturally embodies the challenges that are unique to stream processing.

On the Greatly Exaggerated Limitations of Streaming

On that note, let’s next talk a bit about what streaming systems can and can’t do, with an emphasis on can. One of the biggest things I want to get across in this chapter is just how capable a well-designed streaming system can be. Streaming systems have historically been relegated to a somewhat niche market of providing low-latency, inaccurate, or speculative results, often in conjunction with a more capable batch system to provide eventually correct results; in other words, the Lambda Architecture.

For those of you not already familiar with the Lambda Architecture, the basic idea is that you run a streaming system alongside a batch system, both performing essentially the same calculation. The streaming system gives you low-latency, inaccurate results (either because of the use of an approximation algorithm, or because the streaming system itself does not provide correctness), and some time later a batch system rolls along and provides you with correct output. Originally proposed by Twitter’s Nathan Marz (creator of Storm), it ended up being quite successful because it was, in fact, a fantastic idea for the time; streaming engines were a bit of a letdown in the correctness department, and batch engines were as inherently unwieldy as you’d expect, so Lambda gave you a way to have your proverbial cake and eat it too. Unfortunately, maintaining a Lambda system is a hassle: you need to build, provision, and maintain two independent versions of your pipeline and then also somehow merge the results from the two pipelines at the end.

As someone who spent years working on a strongly consistent streaming engine, I also found the entire principle of the Lambda Architecture a bit unsavory. Unsurprisingly, I was a huge fan of Jay Kreps’ “Questioning the Lambda Architecture” post when it came out. Here was one of the first highly visible statements against the necessity of dual-mode execution. Delightful. Kreps addressed the issue of repeatability in the context of using a replayable system like Kafka as the streaming interconnect, and went so far as to propose the Kappa Architecture, which basically means running a single pipeline using a well-designed system that’s appropriately built for the job at hand. I’m not convinced that notion requires its own Greek letter name, but I fully support the idea in principle.

Quite honestly, I’d take things a step further. I would argue that well-designed streaming systems actually provide a strict superset of batch functionality. Modulo perhaps an efficiency delta, there should be no need for batch systems as they exist today. And kudos to the Apache Flink folks for taking this idea to heart and building a system that’s all-streaming-all-the-time under the covers, even in “batch” mode; I love it.

The corollary of all this is that broad maturation of streaming systems combined with robust frameworks for unbounded data processing will in time allow for the relegation of the Lambda Architecture to the antiquity of big data history where it belongs. I believe the time has come to make this a reality. Because to do so—that is, to beat batch at its own game—you really only need two things:

- Correctness

-

This gets you parity with batch. At the core, correctness boils down to consistent storage. Streaming systems need a method for checkpointing persistent state over time (something Kreps has talked about in his “Why local state is a fundamental primitive in stream processing” post), and it must be well designed enough to remain consistent in light of machine failures. When Spark Streaming first appeared in the public big data scene a few years ago, it was a beacon of consistency in an otherwise dark streaming world. Thankfully, things have improved substantially since then, but it is remarkable how many streaming systems still try to get by without strong consistency.

To reiterate—because this point is important: strong consistency is required for exactly-once processing,3 which is required for correctness, which is a requirement for any system that’s going to have a chance at meeting or exceeding the capabilities of batch systems. Unless you just truly don’t care about your results, I implore you to shun any streaming system that doesn’t provide strongly consistent state. Batch systems don’t require you to verify ahead of time if they are capable of producing correct answers; don’t waste your time on streaming systems that can’t meet that same bar.

If you’re curious to learn more about what it takes to get strong consistency in a streaming system, I recommend you check out the MillWheel, Spark Streaming, and Flink snapshotting papers. All three spend a significant amount of time discussing consistency. Reuven will dive into consistency guarantees in Chapter 5, and if you still find yourself craving more, there’s a large amount of quality information on this topic in the literature and elsewhere.

- Tools for reasoning about time

-

This gets you beyond batch. Good tools for reasoning about time are essential for dealing with unbounded, unordered data of varying event-time skew. An increasing number of modern datasets exhibit these characteristics, and existing batch systems (as well as many streaming systems) lack the necessary tools to cope with the difficulties they impose (though this is now rapidly changing, even as I write this). We will spend the bulk of this book explaining and focusing on various facets of this point.

To begin with, we get a basic understanding of the important concept of time domains, after which we take a deeper look at what I mean by unbounded, unordered data of varying event-time skew. We then spend the rest of this chapter looking at common approaches to bounded and unbounded data processing, using both batch and streaming systems.

Event Time Versus Processing Time

To speak cogently about unbounded data processing requires a clear understanding of the domains of time involved. Within any data processing system, there are typically two domains of time that we care about:

- Event time

-

This is the time at which events actually occurred.

- Processing time

-

This is the time at which events are observed in the system.

Not all use cases care about event times (and if yours doesn’t, hooray! your life is easier), but many do. Examples include characterizing user behavior over time, most billing applications, and many types of anomaly detection, to name a few.

In an ideal world, event time and processing time would always be equal, with events being processed immediately as they occur. Reality is not so kind, however, and the skew between event time and processing time is not only nonzero, but often a highly variable function of the characteristics of the underlying input sources, execution engine, and hardware. Things that can affect the level of skew include the following:

-

Shared resource limitations, like network congestion, network partitions, or shared CPU in a nondedicated environment

-

Software causes such as distributed system logic, contention, and so on

-

Features of the data themselves, like key distribution, variance in throughput, or variance in disorder (i.e., a plane full of people taking their phones out of airplane mode after having used them offline for the entire flight)

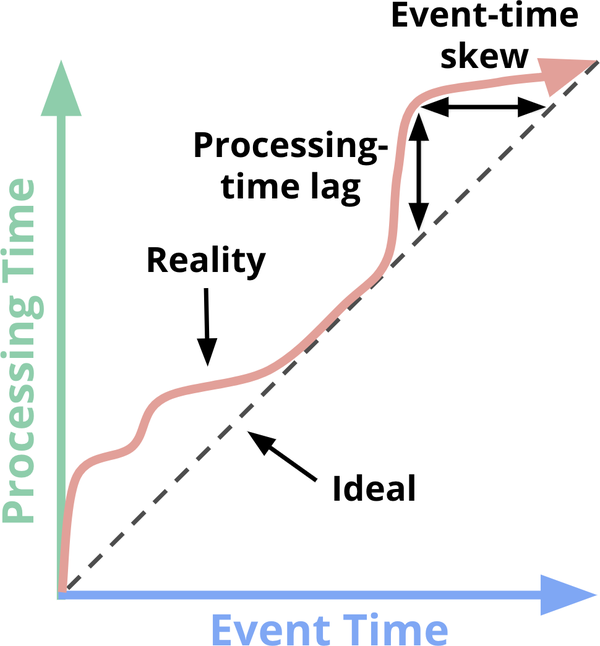

As a result, if you plot the progress of event time and processing time in any real-world system, you typically end up with something that looks a bit like the red line in Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1. Time-domain mapping. The x-axis represents event-time completeness in the system; that is, the time X in event time up to which all data with event times less than X have been observed. The y-axis4 represents the progress of processing time; that is, normal clock time as observed by the data processing system as it executes.

In Figure 1-1, the black dashed line with slope of 1 represents the ideal, where processing time and event time are exactly equal; the red line represents reality. In this example, the system lags a bit at the beginning of processing time, veers closer toward the ideal in the middle, and then lags again a bit toward the end. At first glance, there are two types of skew visible in this diagram, each in different time domains:

- Processing time

-

The vertical distance between the ideal and the red line is the lag in the processing-time domain. That distance tells you how much delay is observed (in processing time) between when the events for a given time occurred and when they were processed. This is the perhaps the more natural and intuitive of the two skews.

- Event time

-

The horizontal distance between the ideal and the red line is the amount of event-time skew in the pipeline at that moment. It tells you how far behind the ideal (in event time) the pipeline is currently.

In reality, processing-time lag and event-time skew at any given point in time are identical; they’re just two ways of looking at the same thing.5 The important takeaway regarding lag/skew is this: Because the overall mapping between event time and processing time is not static (i.e., the lag/skew can vary arbitrarily over time), this means that you cannot analyze your data solely within the context of when they are observed by your pipeline if you care about their event times (i.e., when the events actually occurred). Unfortunately, this is the way many systems designed for unbounded data have historically operated. To cope with the infinite nature of unbounded datasets, these systems typically provide some notion of windowing the incoming data. We discuss windowing in great depth a bit later, but it essentially means chopping up a dataset into finite pieces along temporal boundaries. If you care about correctness and are interested in analyzing your data in the context of their event times, you cannot define those temporal boundaries using processing time (i.e., processing-time windowing), as many systems do; with no consistent correlation between processing time and event time, some of your event-time data are going to end up in the wrong processing-time windows (due to the inherent lag in distributed systems, the online/offline nature of many types of input sources, etc.), throwing correctness out the window, as it were. We look at this problem in more detail in a number of examples in the sections that follow, as well as the remainder of the book.

Unfortunately, the picture isn’t exactly rosy when windowing by event time, either. In the context of unbounded data, disorder and variable skew induce a completeness problem for event-time windows: lacking a predictable mapping between processing time and event time, how can you determine when you’ve observed all of the data for a given event time X? For many real-world data sources, you simply can’t. But the vast majority of data processing systems in use today rely on some notion of completeness, which puts them at a severe disadvantage when applied to unbounded datasets.

I propose that instead of attempting to groom unbounded data into finite batches of information that eventually become complete, we should be designing tools that allow us to live in the world of uncertainty imposed by these complex datasets. New data will arrive, old data might be retracted or updated, and any system we build should be able to cope with these facts on its own, with notions of completeness being a convenient optimization for specific and appropriate use cases rather than a semantic necessity across all of them.

Before getting into specifics about what such an approach might look like, let’s finish up one more useful piece of background: common data processing patterns.

Data Processing Patterns

At this point, we have enough background established that we can begin looking at the core types of usage patterns common across bounded and unbounded data processing today. We look at both types of processing and, where relevant, within the context of the two main types of engines we care about (batch and streaming, where in this context, I’m essentially lumping microbatch in with streaming because the differences between the two aren’t terribly important at this level).

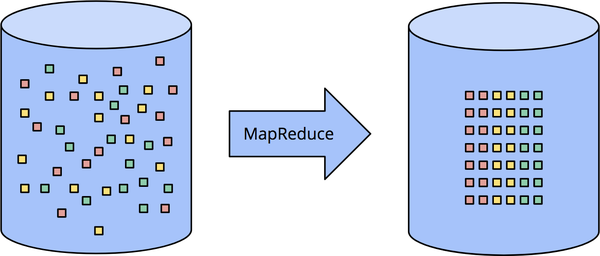

Bounded Data

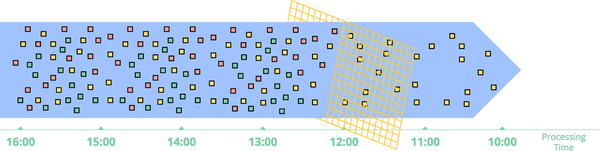

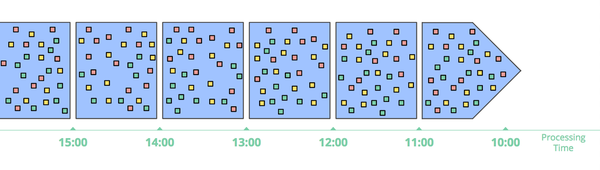

Processing bounded data is conceptually quite straightforward, and likely familiar to everyone. In Figure 1-2, we start out on the left with a dataset full of entropy. We run it through some data processing engine (typically batch, though a well-designed streaming engine would work just as well), such as MapReduce, and on the right side end up with a new structured dataset with greater inherent value.

Figure 1-2. Bounded data processing with a classic batch engine. A finite pool of unstructured data on the left is run through a data processing engine, resulting in corresponding structured data on the right.

Though there are of course infinite variations on what you can actually calculate as part of this scheme, the overall model is quite simple. Much more interesting is the task of processing an unbounded dataset. Let’s now look at the various ways unbounded data are typically processed, beginning with the approaches used with traditional batch engines and then ending up with the approaches you can take with a system designed for unbounded data, such as most streaming or microbatch engines.

Unbounded Data: Batch

Batch engines, though not explicitly designed with unbounded data in mind, have nevertheless been used to process unbounded datasets since batch systems were first conceived. As you might expect, such approaches revolve around slicing up the unbounded data into a collection of bounded datasets appropriate for batch processing.

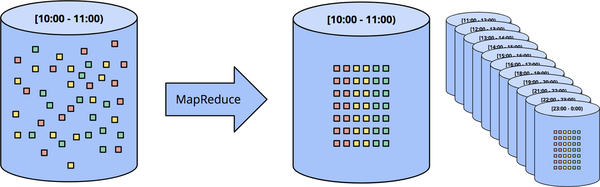

Fixed windows

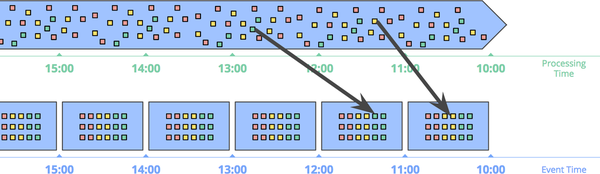

The most common way to process an unbounded dataset using repeated runs of a batch engine is by windowing the input data into fixed-size windows and then processing each of those windows as a separate, bounded data source (sometimes also called tumbling windows), as in Figure 1-3. Particularly for input sources like logs, for which events can be written into directory and file hierarchies whose names encode the window they correspond to, this sort of thing appears quite straightforward at first blush because you’ve essentially performed the time-based shuffle to get data into the appropriate event-time windows ahead of time.

In reality, however, most systems still have a completeness problem to deal with (What if some of your events are delayed en route to the logs due to a network partition? What if your events are collected globally and must be transferred to a common location before processing? What if your events come from mobile devices?), which means some sort of mitigation might be necessary (e.g., delaying processing until you’re sure all events have been collected or reprocessing the entire batch for a given window whenever data arrive late).

Figure 1-3. Unbounded data processing via ad hoc fixed windows with a classic batch engine. An unbounded dataset is collected up front into finite, fixed-size windows of bounded data that are then processed via successive runs a of classic batch engine.

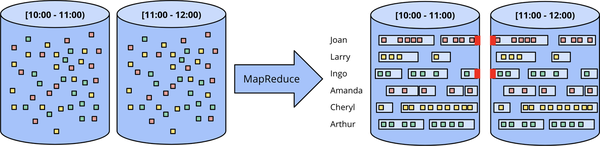

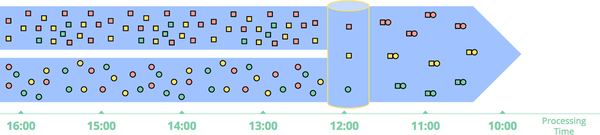

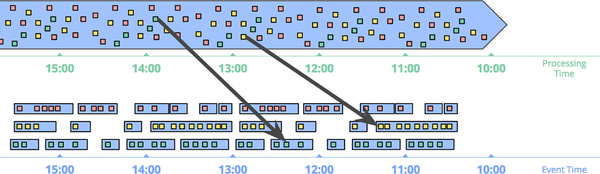

Sessions

This approach breaks down even more when you try to use a batch engine to process unbounded data into more sophisticated windowing strategies, like sessions. Sessions are typically defined as periods of activity (e.g., for a specific user) terminated by a gap of inactivity. When calculating sessions using a typical batch engine, you often end up with sessions that are split across batches, as indicated by the red marks in Figure 1-4. We can reduce the number of splits by increasing batch sizes, but at the cost of increased latency. Another option is to add additional logic to stitch up sessions from previous runs, but at the cost of further complexity.

Figure 1-4. Unbounded data processing into sessions via ad hoc fixed windows with a classic batch engine. An unbounded dataset is collected up front into finite, fixed-size windows of bounded data that are then subdivided into dynamic session windows via successive runs a of classic batch engine.

Either way, using a classic batch engine to calculate sessions is less than ideal. A nicer way would be to build up sessions in a streaming manner, which we look at later on.

Unbounded Data: Streaming

Contrary to the ad hoc nature of most batch-based unbounded data processing approaches, streaming systems are built for unbounded data. As we talked about earlier, for many real-world, distributed input sources, you not only find yourself dealing with unbounded data, but also data such as the following:

-

Highly unordered with respect to event times, meaning that you need some sort of time-based shuffle in your pipeline if you want to analyze the data in the context in which they occurred.

-

Of varying event-time skew, meaning that you can’t just assume you’ll always see most of the data for a given event time X within some constant epsilon of time Y.

There are a handful of approaches that you can take when dealing with data that have these characteristics. I generally categorize these approaches into four groups: time-agnostic, approximation, windowing by processing time, and windowing by event time.

Let’s now spend a little bit of time looking at each of these approaches.

Time-agnostic

Time-agnostic processing is used for cases in which time is essentially irrelevant; that is, all relevant logic is data driven. Because everything about such use cases is dictated by the arrival of more data, there’s really nothing special a streaming engine has to support other than basic data delivery. As a result, essentially all streaming systems in existence support time-agnostic use cases out of the box (modulo system-to-system variances in consistency guarantees, of course, if you care about correctness). Batch systems are also well suited for time-agnostic processing of unbounded data sources by simply chopping the unbounded source into an arbitrary sequence of bounded datasets and processing those datasets independently. We look at a couple of concrete examples in this section, but given the straightforwardness of handling time-agnostic processing (from a temporal perspective at least), we won’t spend much more time on it beyond that.

Filtering

A very basic form of time-agnostic processing is filtering, an example of which is rendered in Figure 1-5. Imagine that you’re processing web traffic logs and you want to filter out all traffic that didn’t originate from a specific domain. You would look at each record as it arrived, see if it belonged to the domain of interest, and drop it if not. Because this sort of thing depends only on a single element at any time, the fact that the data source is unbounded, unordered, and of varying event-time skew is irrelevant.

Figure 1-5. Filtering unbounded data. A collection of data (flowing left to right) of varying types is filtered into a homogeneous collection containing a single type.

Inner joins

Another time-agnostic example is an inner join, diagrammed in Figure 1-6. When joining two unbounded data sources, if you care only about the results of a join when an element from both sources arrive, there’s no temporal element to the logic. Upon seeing a value from one source, you can simply buffer it up in persistent state; only after the second value from the other source arrives do you need to emit the joined record. (In truth, you’d likely want some sort of garbage collection policy for unemitted partial joins, which would likely be time based. But for a use case with little or no uncompleted joins, such a thing might not be an issue.)

Figure 1-6. Performing an inner join on unbounded data. Joins are produced when matching elements from both sources are observed.

Switching semantics to some sort of outer join introduces the data completeness problem we’ve talked about: after you’ve seen one side of the join, how do you know whether the other side is ever going to arrive or not? Truth be told, you don’t, so you need to introduce some notion of a timeout, which introduces an element of time. That element of time is essentially a form of windowing, which we’ll look at more closely in a moment.

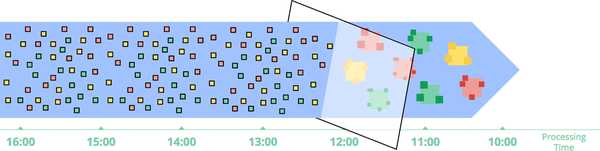

Approximation algorithms

The second major category of approaches is approximation algorithms, such as approximate Top-N, streaming k-means, and so on. They take an unbounded source of input and provide output data that, if you squint at them, look more or less like what you were hoping to get, as in Figure 1-7. The upside of approximation algorithms is that, by design, they are low overhead and designed for unbounded data. The downsides are that a limited set of them exist, the algorithms themselves are often complicated (which makes it difficult to conjure up new ones), and their approximate nature limits their utility.

Figure 1-7. Computing approximations on unbounded data. Data are run through a complex algorithm, yielding output data that look more or less like the desired result on the other side.

It’s worth noting that these algorithms typically do have some element of time in their design (e.g., some sort of built-in decay). And because they process elements as they arrive, that time element is usually processing-time based. This is particularly important for algorithms that provide some sort of provable error bounds on their approximations. If those error bounds are predicated on data arriving in order, they mean essentially nothing when you feed the algorithm unordered data with varying event-time skew. Something to keep in mind.

Approximation algorithms themselves are a fascinating subject, but as they are essentially another example of time-agnostic processing (modulo the temporal features of the algorithms themselves), they’re quite straightforward to use and thus not worth further attention, given our current focus.

Windowing

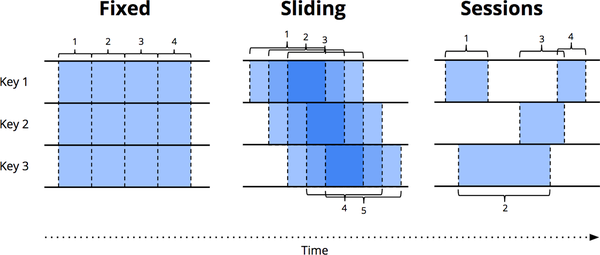

The remaining two approaches for unbounded data processing are both variations of windowing. Before diving into the differences between them, I should make it clear exactly what I mean by windowing, insomuch as we touched on it only briefly in the previous section. Windowing is simply the notion of taking a data source (either unbounded or bounded), and chopping it up along temporal boundaries into finite chunks for processing. Figure 1-8 shows three different windowing patterns.

Figure 1-8. Windowing strategies. Each example is shown for three different keys, highlighting the difference between aligned windows (which apply across all the data) and unaligned windows (which apply across a subset of the data).

Let’s take a closer look at each strategy:

- Fixed windows (aka tumbling windows)

-

We discussed fixed windows earlier. Fixed windows slice time into segments with a fixed-size temporal length. Typically (as shown in Figure 1-9), the segments for fixed windows are applied uniformly across the entire dataset, which is an example of aligned windows. In some cases, it’s desirable to phase-shift the windows for different subsets of the data (e.g., per key) to spread window completion load more evenly over time, which instead is an example of unaligned windows because they vary across the data.6

- Sliding windows (aka hopping windows)

-

A generalization of fixed windows, sliding windows are defined by a fixed length and a fixed period. If the period is less than the length, the windows overlap. If the period equals the length, you have fixed windows. And if the period is greater than the length, you have a weird sort of sampling window that looks only at subsets of the data over time. As with fixed windows, sliding windows are typically aligned, though they can be unaligned as a performance optimization in certain use cases. Note that the sliding windows in Figure 1-8 are drawn as they are to give a sense of sliding motion; in reality, all five windows would apply across the entire dataset.

- Sessions

-

An example of dynamic windows, sessions are composed of sequences of events terminated by a gap of inactivity greater than some timeout. Sessions are commonly used for analyzing user behavior over time, by grouping together a series of temporally related events (e.g., a sequence of videos viewed in one sitting). Sessions are interesting because their lengths cannot be defined a priori; they are dependent upon the actual data involved. They’re also the canonical example of unaligned windows because sessions are practically never identical across different subsets of data (e.g., different users).

The two domains of time we discussed earlier (processing time and event time) are essentially the two we care about.7 Windowing makes sense in both domains, so let’s look at each in detail and see how they differ. Because processing-time windowing has historically been more common, we’ll start there.

Windowing by processing time

When windowing by processing time, the system essentially buffers up incoming data into windows until some amount of processing time has passed. For example, in the case of five-minute fixed windows, the system would buffer data for five minutes of processing time, after which it would treat all of the data it had observed in those five minutes as a window and send them downstream for processing.

Figure 1-9. Windowing into fixed windows by processing time. Data are collected into windows based on the order they arrive in the pipeline.

There are a few nice properties of processing-time windowing:

-

It’s simple. The implementation is extremely straightforward because you never worry about shuffling data within time. You just buffer things as they arrive and send them downstream when the window closes.

-

Judging window completeness is straightforward. Because the system has perfect knowledge of whether all inputs for a window have been seen, it can make perfect decisions about whether a given window is complete. This means there is no need to be able to deal with “late” data in any way when windowing by processing time.

-

If you’re wanting to infer information about the source as it is observed, processing-time windowing is exactly what you want. Many monitoring scenarios fall into this category. Imagine tracking the number of requests per second sent to a global-scale web service. Calculating a rate of these requests for the purpose of detecting outages is a perfect use of processing-time windowing.

Good points aside, there is one very big downside to processing-time windowing: if the data in question have event times associated with them, those data must arrive in event-time order if the processing-time windows are to reflect the reality of when those events actually happened. Unfortunately, event-time ordered data are uncommon in many real-world, distributed input sources.

As a simple example, imagine any mobile app that gathers usage statistics for later processing. For cases in which a given mobile device goes offline for any amount of time (brief loss of connectivity, airplane mode while flying across the country, etc.), the data recorded during that period won’t be uploaded until the device comes online again. This means that data might arrive with an event-time skew of minutes, hours, days, weeks, or more. It’s essentially impossible to draw any sort of useful inferences from such a dataset when windowed by processing time.

As another example, many distributed input sources might seem to provide event-time ordered (or very nearly so) data when the overall system is healthy. Unfortunately, the fact that event-time skew is low for the input source when healthy does not mean it will always stay that way. Consider a global service that processes data collected on multiple continents. If network issues across a bandwidth-constrained transcontinental line (which, sadly, are surprisingly common) further decrease bandwidth and/or increase latency, suddenly a portion of your input data might begin arriving with much greater skew than before. If you are windowing those data by processing time, your windows are no longer representative of the data that actually occurred within them; instead, they represent the windows of time as the events arrived at the processing pipeline, which is some arbitrary mix of old and current data.

What we really want in both of those cases is to window data by their event times in a way that is robust to the order of arrival of events. What we really want is event-time windowing.

Windowing by event time

Event-time windowing is what you use when you need to observe a data source in finite chunks that reflect the times at which those events actually happened. It’s the gold standard of windowing. Prior to 2016, most data processing systems in use lacked native support for it (though any system with a decent consistency model, like Hadoop or Spark Streaming 1.x, could act as a reasonable substrate for building such a windowing system). I’m happy to say that the world of today looks very different, with multiple systems, from Flink to Spark to Storm to Apex, natively supporting event-time windowing of some sort.

Figure 1-10 shows an example of windowing an unbounded source into one-hour fixed windows.

Figure 1-10. Windowing into fixed windows by event time. Data are collected into windows based on the times at which they occurred. The black arrows call out example data that arrived in processing-time windows that differed from the event-time windows to which they belonged.

The black arrows in Figure 1-10 call out two particularly interesting pieces of data. Each arrived in processing-time windows that did not match the event-time windows to which each bit of data belonged. As such, if these data had been windowed into processing-time windows for a use case that cared about event times, the calculated results would have been incorrect. As you would expect, event-time correctness is one nice thing about using event-time windows.

Another nice thing about event-time windowing over an unbounded data source is that you can create dynamically sized windows, such as sessions, without the arbitrary splits observed when generating sessions over fixed windows (as we saw previously in the sessions example from “Unbounded Data: Streaming”), as demonstrated in Figure 1-11.

Figure 1-11. Windowing into session windows by event time. Data are collected into session windows capturing bursts of activity based on the times that the corresponding events occurred. The black arrows again call out the temporal shuffle necessary to put the data into their correct event-time locations.

Of course, powerful semantics rarely come for free, and event-time windows are no exception. Event-time windows have two notable drawbacks due to the fact that windows must often live longer (in processing time) than the actual length of the window itself:

- Buffering

-

Due to extended window lifetimes, more buffering of data is required. Thankfully, persistent storage is generally the cheapest of the resource types most data processing systems depend on (the others being primarily CPU, network bandwidth, and RAM). As such, this problem is typically much less of a concern than you might think when using any well-designed data processing system with strongly consistent persistent state and a decent in-memory caching layer. Also, many useful aggregations do not require the entire input set to be buffered (e.g., sum or average), but instead can be performed incrementally, with a much smaller, intermediate aggregate stored in persistent state.

- Completeness

-

Given that we often have no good way of knowing when we’ve seen all of the data for a given window, how do we know when the results for the window are ready to materialize? In truth, we simply don’t. For many types of inputs, the system can give a reasonably accurate heuristic estimate of window completion via something like the watermarks found in MillWheel, Cloud Dataflow, and Flink (which we talk about more in Chapters 3 and 4). But for cases in which absolute correctness is paramount (again, think billing), the only real option is to provide a way for the pipeline builder to express when they want results for windows to be materialized and how those results should be refined over time. Dealing with window completeness (or lack thereof) is a fascinating topic but one perhaps best explored in the context of concrete examples, which we look at next.

Summary

Whew! That was a lot of information. If you’ve made it this far, you are to be commended! But we are only just getting started. Before forging ahead to looking in detail at the Beam Model approach, let’s briefly step back and recap what we’ve learned so far. In this chapter, we’ve done the following:

-

Clarified terminology, focusing the definition of “streaming” to refer to systems built with unbounded data in mind, while using more descriptive terms like approximate/speculative results for distinct concepts often categorized under the “streaming” umbrella. Additionally, we highlighted two important dimensions of large-scale datasets: cardinality (i.e., bounded versus unbounded) and constitution (i.e., table versus stream), the latter of which will consume much of the second half of the book.

-

Assessed the relative capabilities of well-designed batch and streaming systems, positing streaming is in fact a strict superset of batch, and that notions like the Lambda Architecture, which are predicated on streaming being inferior to batch, are destined for retirement as streaming systems mature.

-

Proposed two high-level concepts necessary for streaming systems to both catch up to and ultimately surpass batch, those being correctness and tools for reasoning about time, respectively.

-

Established the important differences between event time and processing time, characterized the difficulties those differences impose when analyzing data in the context of when they occurred, and proposed a shift in approach away from notions of completeness and toward simply adapting to changes in data over time.

-

Looked at the major data processing approaches in common use today for bounded and unbounded data, via both batch and streaming engines, roughly categorizing the unbounded approaches into: time-agnostic, approximation, windowing by processing time, and windowing by event time.

Next up, we dive into the details of the Beam Model, taking a conceptual look at how we’ve broken up the notion of data processing across four related axes: what, where, when, and how. We also take a detailed look at processing a simple, concrete example dataset across multiple scenarios, highlighting the plurality of use cases enabled by the Beam Model, with some concrete APIs to ground us in reality. These examples will help drive home the notions of event time and processing time introduced in this chapter while additionally exploring new concepts such as watermarks.

1 For completeness, it’s perhaps worth calling out that this definition includes both true streaming as well as microbatch implementations. For those of you who aren’t familiar with microbatch systems, they are streaming systems that use repeated executions of a batch processing engine to process unbounded data. Spark Streaming is the canonical example in the industry.

2 Readers familiar with my original “Streaming 101” article might recall that I rather emphatically encouraged the abandonment of the term “stream” when referring to datasets. That never caught on, which I initially thought was due to its catchiness and pervasive existing usage. In retrospect, however, I think I was simply wrong. There actually is great value in distinguishing between the two different types of dataset constitutions: tables and streams. Indeed, most of the second half of this book is dedicated to understanding the relationship between those two.

3 If you’re unfamiliar with what I mean when I say exactly-once, it’s referring to a specific type of consistency guarantee that certain data processing frameworks provide. Consistency guarantees are typically bucketed into three main classes: at-most-once processing, at-least-once processing, and exactly-once processing. Note that the names in use here refer to the effective semantics as observed within the outputs generated by the pipeline, not the actual number of times a pipeline might process (or attempt to process) any given record. For this reason, the term effectively-once is sometimes used instead of exactly-once, since it’s more representative of the underlying nature of things. Reuven covers these concepts in much more detail in Chapter 5.

4 Since the original publication of “Streaming 101,” numerous individuals have pointed out to me that it would have been more intuitive to place processing time on the x-axis and event time on the y-axis. I do agree that swapping the two axes would initially feel more natural, as event time seems like the dependent variable to processing time’s independent variable. However, because both variables are monotonic and intimately related, they’re effectively interdependent variables. So I think from a technical perspective you just have to pick an axis and stick with it. Math is confusing (especially outside of North America, where it suddenly becomes plural and gangs up on you).

5 This result really shouldn’t be surprising (but was for me, hence why I’m pointing it out), because we’re effectively creating a right triangle with the ideal line when measuring the two types of skew/lag. Maths are cool.

6 We look at aligned fixed windows in detail in Chapter 2, and unaligned fixed windows in Chapter 4.

7 If you poke around enough in the academic literature or SQL-based streaming systems, you’ll also come across a third windowing time domain: tuple-based windowing (i.e., windows whose sizes are counted in numbers of elements). However, tuple-based windowing is essentially a form of processing-time windowing in which elements are assigned monotonically increasing timestamps as they arrive at the system. As such, we won’t discuss tuple-based windowing in detail any further.

Get Streaming Systems now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.