How do we deliver great products and services in an uncertain world? The thing to keep in mind, not just in the abstract, but truly and viscerally, are your customers and their abilities, needs, and desires.

This is a crucial time for businesses around the world—and we use the word "crucial" intentionally. We're sitting at the crux of a fundamental shift in the ways in which businesses engage with their customers. There are many reasons for this shift—globalization, containerization, digitization—and these emerging forces are causing consternation for businesses that don't quite know how to react. The old tools at their disposal, such as efficiency, optimization, just-in-time manufacturing, blitz marketing, and outsourcing no longer provide the gains or competitive advantages they once did.

The key to succeeding in the contemporary marketplace is to fundamentally change your relationship with customers. Once you stop thinking of your customers as consumers and begin approaching them as people, you'll find a whole new world of opportunities to meet their needs and desires.

Seizing those opportunities is another matter. Businesses must stop thinking of their products and services as standalone offerings, and instead adopt a systems-oriented mindset that better serves people's actual needs. Furthermore, to continually deliver high-quality products, businesses need to incorporate design approaches into their standard work practices and build an internal design competency. This doesn't necessarily mean hiring designers, but at the very least it is critical to understand and appreciate the values and worldview that designers often bring.

Of course, it doesn't end there; you still have to deliver your product or service. Contemporary life is too uncertain for overlong development cycles. By the time a product finally gets released, the world has often moved on. And so businesses need to move away from their onerous technological and engineering approaches, embracing nimbler, more flexible means when building products and services.

In this book, we'll share what we've learned through observing industry trends and conducting our own work at Adaptive Path. But first, we'll tell a story. This is a story about the birth of consumer electronics (although, technically, electricity isn't even a part of the story).

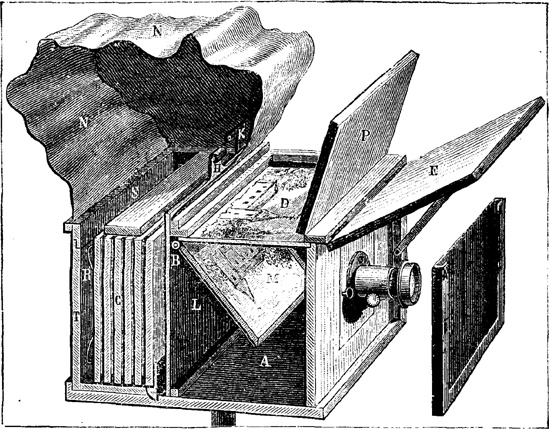

In 1886, Scientific American hailed "a new photographic apparatus" (Figure 1-1) as an exemplar of contemporary product design.

Note the complexity of the magazine's description:

This apparatus consists of a box containing a camera, A, and a frame, C, containing the desired number of plates, each held in a small frame of black Bristol board. The camera contains a mirror, M, which pivots upon an axis and is maneuvered by the extreme bottom, B. This mirror stops at an angle of 45°, and sends the image coming from the objective to the horizontal plate, D, at the upper part of the camera. The image thus reflected is righted upon this plate.

As the objective is of short focus, every object situated beyond a distance of three yards from the apparatus is in focus. In exceptional cases, where the operator might be nearer the object to be photographed, the focusing would be done by means of the rack of the objective. The latter can also slide up and down, so that the apparatus need not be inclined when buildings or high trees are being photographed. The door, E, performs the role of a shade. When the apparatus has been fixed upon its tripod and properly directed, all the operator has to do is to close the door, P, and raise the mirror, M, by turning the button, B, and then expose the plate. The sensitized plates are introduced into the apparatus through the door, I, and are always brought automatically to the focus of the objective through the pressure of the springs, R. The shutter of the frame, B, opens through a hook, H, within the pocket, N. After exposure, each plate is lifted by means of the extractor, K, into the pocket, whence it is taken by hand and introduced through a slit, S, behind the springs, R, and the other plates that the frame contains. All these operations are performed in the interior of the pocket, N, through the impermeable, triple fabric of which no light can enter.

An automatic marker shows the number of plates exposed. When the operations are finished, the objective is put back in the interior of the camera, the doors, P and E, are closed, and the pocket is rolled up. The apparatus is thus hermetically closed, and, containing all the accessories, forms one of the most practical of systems for the itinerant photographer.

—La Nature

This passage has something of the quality of a modern-day consumer electronics operating manual. As "the most practical" system for a photographer on the go, doubtless this was on the cutting edge. However, given the complexity of its operation (by reaching the letter "S," the reader must understand 19 separate elements), it's no wonder that, at the time, photography was the province of either professionals or obsessed hobbyists—the geeks of their era.

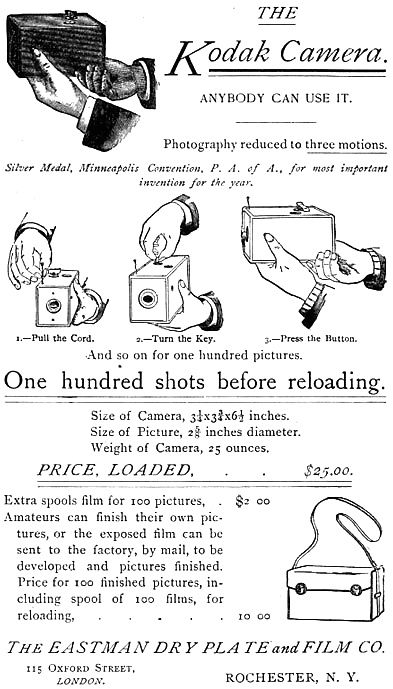

Then, in 1888, an inventor named George Eastman designed, manufactured, and marketed a camera that forever changed photography, and also consumer products as a whole (Figure 1-2). Eastman had invented a new kind of film four years earlier, roll film, which was much easier to handle than fragile photographic plates. Had Eastman taken a typical engineering approach to designing his roll-film camera, he would have copied the complexity of the camera described above, just on a smaller scale, thus providing an incremental improvement on his predecessors. Instead, he recognized that his roll film could lead to a revolution if he focused on the experience he wanted to deliver, an experience captured in his advertising slogan, "You press the button, we do the rest."

Thanks to the capabilities of this new film, operating the new camera was extremely simple. Unlike the apparatus described above, the user never needed to open this camera, and there were only three steps to take a picture (Figure 1-3): Pull the Cord (to prepare the shutter); Turn the Key (to advance the film); and Press the Button (to release the shutter). After you'd used 100 exposures, you would send the camera (or just the roll of film) to Eastman, and wait while your pictures were professionally developed and printed for you.

This level of accessibility began the consumer revolution in photography, and Eastman's camera, the Kodak, became one of the first consumer technology brands. By approaching design with the customer in mind, and not simply as a collection of functional requirements, Eastman arrived at a radically different result.

Get Subject To Change: Creating Great Products & Services for an Uncertain World now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.