OS X can run two different kinds of programs, each with different characteristics: Cocoa and Carbon.

The explanation involves a little bit of history. When Mac OS X came along in 2001, Apple gave software companies a choice: They could either adapt their existing software to the new operating system—or rewrite it from the ground up.

If programmers were willing to put some effort into getting with the OS X program, they could update their existing software. These are what Apple calls Carbonized programs, named for the technology (Carbon) that permits them to run on OS X.

But as OS X became popular, more and more software companies opted to create programs exclusively for it. The geeks call such programs Cocoa applications. Although they look exactly like Carbonized programs, they feel a bit more solid. And they offer a number of special features that Carbonized programs don’t offer:

Note

The following features appear in almost all Cocoa programs. That’s not to say that you’ll never see these features in Carbonized programs; the occasional Carbon program may offer one of these features or another.

The Fonts pane: When you use a Carbon program, you usually access these fonts the same way as always: using a Font menu. But when you use a Cocoa program, you get the Fonts pane, which makes it far easier to organize, search, and use your font collection. Chapter 9 describes fonts, and the Fonts pane, in more detail.

Retina friendliness: In general, Cocoa programs automatically sharpen up their text when you view it on a Retina display—Apple’s name for super-high-resolution screens like the one on its latest MacBook laptops. Text in Carbonized programs, on the other hand, looks blotchy and awful until their software companies make the effort to make them Retina-friendly.

Title bar tricks: By dragging the tiny icon next to the document’s name in an open window, you can perform stunts—like dragging that little icon to the desktop or to the Dock icon of a different program for opening—right from your document’s title bar.

Secret keyboard shortcuts: If you’re a card-carrying member of KIAFTMA (the Keyboard Is Always Faster Than the Mouse Association), you’ll love these additional keyboard navigation strokes:

Control-A. Moves your insertion point to the beginning of the paragraph. (Mnemonic: A = beginning of the Alphabet.)

Control-E. Deposits your insertion point at the end of the paragraph. (Mnemonic: E = End.)

Control-D. Forward delete (deletes the letter to the right of the insertion point).

Control-K. Instantly deletes all text from the insertion point to the right end of the line. (Mnemonic: K = Kills the rest of the line.)

Control-O. Inserts a paragraph break, much like Return, but leaves the insertion point where it was, above the break. This is the ideal trick for breaking a paragraph in half when you’ve just thought of a better ending for the first part.

Control-T. Moves the insertion point one letter to the right—and, along with it, drags whichever letter was to its left. (Mnemonic: T = Transpose letters.)

Option-Delete. Deletes the entire word to the left of the insertion point. When you’re typing along in a hurry and discover that you’ve just made a typo, this is the keystroke you want. It’s much faster to nuke the previous word and retype it than to fiddle around with the mouse and the insertion point just to fix one letter.

Cool text-selection tricks: By holding down certain keys while dragging through text in a Cocoa program, you gain some wild and wacky text-selection powers (especially useful in, for example, TextEdit and Pages):

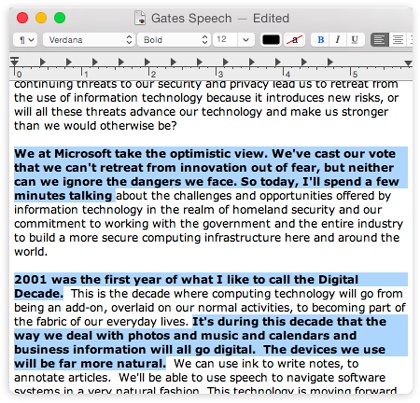

Highlight only one column by Option-dragging. Instead of highlighting all the text, margin to margin, you get only the text within your selection rectangle.

Highlight several passages simultaneously by ⌘-dragging. Each time you ⌘-drag, you highlight another block of text, even though the earlier blocks are still selected (see Figure 4-3).

These days, almost every name-brand program is a true Cocoa application, including Photoshop, Microsoft Office, FileMaker, iMovie, iPhoto, Safari, Messages, TextEdit, Stickies, Mail, Contacts, and so on.

Figure 4-3. The beauty of being able to select multiple blobs of text is that you can format all of them simultaneously (making them bold, for example) with one click. You can also copy the selected portions; when you paste them into a different document, you get a tidy excerpt containing only the parts you wanted, all run together.

Get Switching to the Mac: The Missing Manual, Yosemite Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.