Chapter 16. Server-Side Authentication and Mocking in Python

Let’s crack on with the server side of our new auth system. In this chapter we’ll do some more mocking, this time with Python. We’ll also find out about how to customise Django’s authentication system.

A Look at Our Spiked Login View

At the end of the last chapter, we had a working client side that was trying to send authentication assertions to our server’s login view. Let’s start by building that view, and then move inwards to build the backend authentication functions.

Here’s the spiked version of our login view:

defpersona_login(request):('login view',file=sys.stderr)#user = PersonaAuthenticationBackend().authenticate(request.POST['assertion'])user=authenticate(assertion=request.POST['assertion'])#ifuserisnotNone:login(request,user)#returnredirect('/')

authenticateis our customised authentication function, which we’ll de-spike later. Its job is to take the assertion from the client side and validate it.

loginis Django’s built-in login function. It stores a session object on the server, tied to the user’s cookies, so that we can recognise them as being an authenticated user on future requests.

Our authenticate function is going to make calls out, over the Internet, to

Mozilla’s servers. We don’t want that to happen in our unit test, so we’ll

want to mock out authenticate.

Mocking in Python

The popular mock package was added to the standard library as part of Python

3.3.[29]

It provides a magical object called a Mock, which is a bit like the Sinon

mock objects we saw in the last chapter, only much cooler. Check this out:

>>> from unittest.mock import Mock >>> m = Mock() >>> m.any_attribute <Mock name='mock.any_attribute' id='140716305179152'> >>> m.foo <Mock name='mock.foo' id='140716297764112'> >>> m.any_method() <Mock name='mock.any_method()' id='140716331211856'> >>> m.foo() <Mock name='mock.foo()' id='140716331251600'> >>> m.called False >>> m.foo.called True >>> m.bar.return_value = 1 >>> m.bar() 1

A mock object would be a pretty neat thing to use to mock out the authenticate

function, wouldn’t it? Here’s how you can do that.

Testing Our View by Mocking Out authenticate

(I trust you to set up a tests folder with a dunderinit. Don’t forget to delete the default tests.py, as well.)

accounts/tests/test_views.py.

fromdjango.testimportTestCasefromunittest.mockimportpatchclassLoginViewTest(TestCase):@patch('accounts.views.authenticate')#deftest_calls_authenticate_with_assertion_from_post(self,mock_authenticate#):mock_authenticate.return_value=None#self.client.post('/accounts/login',{'assertion':'assert this'})mock_authenticate.assert_called_once_with(assertion='assert this')#

The decorator called

patchis a bit like the Sinonmockfunction we saw in the last chapter. It lets you specify an object you want to “mock out”. In this case we’re mocking out theauthenticatefunction, which we expect to be using in accounts/views.py.

The decorator adds the mock object as an additional argument to the function it’s applied to.

We can then configure the mock so that it has certain behaviours. Having

authenticatereturnNoneis the simplest, so we set the special.return_valueattribute. Otherwise it would return another mock, and that would probably confuse our view.

Mocks can make assertions! In this case, they can check whether they were called, and what with.

So what does that give us?

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

AttributeError: <module 'accounts.views' from

'/workspace/superlists/accounts/views.py'> does not have the attribute

'authenticate'We tried to patch something that doesn’t exist yet. We need to import

authenticate into our views.py:[30]

accounts/views.py.

fromdjango.contrib.authimportauthenticate

Now we get:

AssertionError: Expected 'authenticate' to be called once. Called 0 times.

That’s our expected failure; to implement, we’ll have to wire up a URL for our login view:

superlists/urls.py.

[...]fromlistsimporturlsaslist_urlsfromaccountsimporturlsasaccount_urlsurlpatterns=[url(r'^$',list_views.home_page,name='home'),url(r'^lists/',include(list_urls)),url(r'^accounts/',include(account_urls)),# url(r'^admin/', include(admin.site.urls)),]

accounts/urls.py.

fromdjango.conf.urlsimporturlfromaccountsimportviewsurlpatterns=[url(r'^login$',views.persona_login,name='persona_login'),]

Will a minimal view do anything?

accounts/views.py.

fromdjango.contrib.authimportauthenticatedefpersona_login():pass

Yep:

TypeError: persona_login() takes 0 positional arguments but 1 was given

And so:

accounts/views.py (ch16l008).

defpersona_login(request):pass

Then:

ValueError: The view accounts.views.persona_login didn't return an HttpResponse object. It returned None instead.

accounts/views.py (ch16l009).

fromdjango.contrib.authimportauthenticatefromdjango.httpimportHttpResponsedefpersona_login(request):returnHttpResponse()

And we’re back to:

AssertionError: Expected 'authenticate' to be called once. Called 0 times.

We try:

accounts/views.py.

defpersona_login(request):authenticate()returnHttpResponse()

And sure enough, we get:

AssertionError: Expected call: authenticate(assertion='assert this') Actual call: authenticate()

And then we can fix that too:

accounts/views.py.

defpersona_login(request):authenticate(assertion=request.POST['assertion'])returnHttpResponse()

OK so far. One Python function mocked and tested.

Checking the View Actually Logs the User In

But our authenticate view also needs to actually log the user in by

calling the Django auth.login function, if authenticate returns a user.

Then it needs to return something other than an empty response—since this is

an Ajax view, it doesn’t need to return HTML, just an “OK” string will do:

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch16l011).

fromdjango.contrib.authimportget_user_modelfromdjango.testimportTestCasefromunittest.mockimportpatchUser=get_user_model()#classLoginViewTest(TestCase):@patch('accounts.views.authenticate')deftest_calls_authenticate_with_assertion_from_post([...]@patch('accounts.views.authenticate')deftest_returns_OK_when_user_found(self,mock_authenticate):user=User.objects.create(='a@b.com')user.backend=''# required for auth_login to workmock_authenticate.return_value=userresponse=self.client.post('/accounts/login',{'assertion':'a'})self.assertEqual(response.content.decode(),'OK')

That test covers the desired response. Now test that the user actually gets logged in correctly. We can do that by inspecting the Django test client, to see if the session cookie has been set correctly.

Tip

Check out the Django docs on authentication at this point.

accounts/tests/test_views.py (ch16l012).

fromdjango.contrib.authimportget_user_model,SESSION_KEY[...]@patch('accounts.views.authenticate')deftest_gets_logged_in_session_if_authenticate_returns_a_user(self,mock_authenticate):user=User.objects.create(='a@b.com')user.backend=''# required for auth_login to workmock_authenticate.return_value=userself.client.post('/accounts/login',{'assertion':'a'})self.assertEqual(self.client.session[SESSION_KEY],str(user.pk))#@patch('accounts.views.authenticate')deftest_does_not_get_logged_in_if_authenticate_returns_None(self,mock_authenticate):mock_authenticate.return_value=Noneself.client.post('/accounts/login',{'assertion':'a'})self.assertNotIn(SESSION_KEY,self.client.session)#

The Django test client keeps track of the session for its user. For the case where the user gets authenticated successfully, we check that their user ID (the primary key, or pk) is associated with their session.

In the case where the user should not be authenticated, the

SESSION_KEYshould not appear in their session.

That gives us two failures:

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

self.assertEqual(self.client.session[SESSION_KEY], str(user.pk))

KeyError: '_auth_user_id'

[...]

AssertionError: '' != 'OK'

+ OKThe Django function that takes care of logging in a user, by marking their

session, is available at django.contrib.auth.login. So we go through another

couple of TDD cycles, until:

accounts/views.py.

fromdjango.contrib.authimportauthenticate,loginfromdjango.httpimportHttpResponsedefpersona_login(request):user=authenticate(assertion=request.POST['assertion'])ifuser:login(request,user)returnHttpResponse('OK')

…

OK

De-spiking Our Custom Authentication Backend: Mocking Out an Internet Request

Our custom authentication backend is next. Here’s how it looked in the spike:

classPersonaAuthenticationBackend(object):defauthenticate(self,assertion):# Send the assertion to Mozilla's verifier service.data={'assertion':assertion,'audience':'localhost'}('sending to mozilla',data,file=sys.stderr)resp=requests.post('https://verifier.login.persona.org/verify',data=data)('got',resp.content,file=sys.stderr)# Did the verifier respond?ifresp.ok:# Parse the responseverification_data=resp.json()# Check if the assertion was validifverification_data['status']=='okay':=verification_data['email']try:returnself.get_user()exceptListUser.DoesNotExist:returnListUser.objects.create(=)defget_user(self,):returnListUser.objects.get(=)

Decoding this:

-

We take an assertion and send it off to Mozilla using

requests.post. -

We check its response code (

resp.ok), and then check for astatus=okayin the response JSON. - We then extract an email address, and either find an existing user with that address, or create a new one.

1 if = 1 More Test

A rule of thumb for these sorts of tests: any if means an extra test, and

any try/except means an extra test, so this should be about four tests. Let’s

start with one:

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py.

fromunittest.mockimportpatchfromdjango.testimportTestCasefromaccounts.authenticationimport(PERSONA_VERIFY_URL,DOMAIN,PersonaAuthenticationBackend)classAuthenticateTest(TestCase):@patch('accounts.authentication.requests.post')deftest_sends_assertion_to_mozilla_with_domain(self,mock_post):backend=PersonaAuthenticationBackend()backend.authenticate('an assertion')mock_post.assert_called_once_with(PERSONA_VERIFY_URL,data={'assertion':'an assertion','audience':DOMAIN})

In authenticate.py we’ll just have a few placeholders:

accounts/authentication.py.

importrequestsPERSONA_VERIFY_URL='https://verifier.login.persona.org/verify'DOMAIN='localhost'classPersonaAuthenticationBackend(object):defauthenticate(self,assertion):pass

At this point we’ll need to:

(virtualenv)$ pip install requestsNote

Don’t forget to add requests to requirements.txt too, or the

next deploy won’t work…

Then let’s see how the tests get on!

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

AssertionError: Expected 'post' to be called once. Called 0 times.And we can get that to passing in three steps (make sure the Goat sees you doing each one individually!):

accounts/authentication.py.

defauthenticate(self,assertion):requests.post(PERSONA_VERIFY_URL,data={'assertion':assertion,'audience':DOMAIN})

Grand:

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

Ran 5 tests in 0.023s

OKNext let’s check that authenticate should return None if it sees an error from

the request:

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py (ch16l020).

@patch('accounts.authentication.requests.post')deftest_returns_none_if_response_errors(self,mock_post):mock_post.return_value.ok=Falsebackend=PersonaAuthenticationBackend()user=backend.authenticate('an assertion')self.assertIsNone(user)

And that passes straight away—we currently return None in all cases!

Patching at the Class Level

Next we want to check that the response JSON has status=okay. Adding this

test would involve a bit of duplication—let’s apply the “three strikes”

rule:

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py (ch16l021).

@patch('accounts.authentication.requests.post')#classAuthenticateTest(TestCase):defsetUp(self):self.backend=PersonaAuthenticationBackend()#deftest_sends_assertion_to_mozilla_with_domain(self,mock_post):self.backend.authenticate('an assertion')mock_post.assert_called_once_with(PERSONA_VERIFY_URL,data={'assertion':'an assertion','audience':DOMAIN})deftest_returns_none_if_response_errors(self,mock_post):mock_post.return_value.ok=False#user=self.backend.authenticate('an assertion')self.assertIsNone(user)deftest_returns_none_if_status_not_okay(self,mock_post):mock_post.return_value.json.return_value={'status':'not okay!'}#user=self.backend.authenticate('an assertion')self.assertIsNone(user)

You can apply a

patchat the class level as well, and that has the effect that every test method in the class will have the patch applied, and the mock injected.

We can now use the

setUpfunction to prepare any useful variables which we’re going to use in all of our tests.

Now each test is only adjusting the setup variables it needs, rather than setting up a load of duplicated boilerplate—it’s more readable.

And that’s all very well, but everything still passes!

OK

Time to test for the positive case where authenticate should return a user

object. We expect this to fail:

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py (ch16l022-1).

fromdjango.contrib.authimportget_user_modelUser=get_user_model()[...]deftest_finds_existing_user_with_email(self,mock_post):mock_post.return_value.json.return_value={'status':'okay','email':'a@b.com'}actual_user=User.objects.create(='a@b.com')found_user=self.backend.authenticate('an assertion')self.assertEqual(found_user,actual_user)

Indeed, a fail:

AssertionError: None != <User: >

Let’s code. We’ll start with a “cheating” implementation, where we just get the first user we find in the database:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l023).

importrequestsfromdjango.contrib.authimportget_user_modelUser=get_user_model()[...]defauthenticate(self,assertion):requests.post(PERSONA_VERIFY_URL,data={'assertion':assertion,'audience':DOMAIN})returnUser.objects.first()

That gets our new test passing, but still, none of the other tests are failing:

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

Ran 8 tests in 0.030s

OKThey’re passing because objects.first() returns None if there are

no users in the database. Let’s make our other cases more realistic,

by making sure there’s always at least one user in the database for all

our tests:

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py (ch16l022-2).

defsetUp(self):self.backend=PersonaAuthenticationBackend()user=User(='other@user.com')user.username='otheruser'#user.save()

That gives us three failures:

FAIL: test_finds_existing_user_with_email AssertionError: <User: otheruser> != <User: > [...] FAIL: test_returns_none_if_response_errors AssertionError: <User: otheruser> is not None [...] FAIL: test_returns_none_if_status_not_okay AssertionError: <User: otheruser> is not None

Let’s start building our guards for cases where authentication should fail—if

the response errors, or if the status is not okay. Suppose we start with this:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l024-1).

defauthenticate(self,assertion):response=requests.post(PERSONA_VERIFY_URL,data={'assertion':assertion,'audience':DOMAIN})ifresponse.json()['status']=='okay':returnUser.objects.first()

That actually fixes two of the tests, slightly surprisingly:

AssertionError: <User: otheruser> != <User: > FAILED (failures=1)

Let’s get the final test passing by retrieving the right user, and then we’ll have a look at that surprise pass:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l024-2).

ifresponse.json()['status']=='okay':returnUser.objects.get(=response.json()['email'])

…

OK

Beware of Mocks in Boolean Comparisons

So how come our test_returns_none_if_response_errors isn’t failing?

Because we’ve mocked out requests.post, the response is a Mock object,

which as you remember, returns all attributes and properties as more

Mocks.[31] So, when we do:

accounts/authentication.py.

ifresponse.json()['status']=='okay':

response is actually a mock, response.json() is a mock, and

response.json()['status'] is a mock too! We end up comparing a mock with the

string “okay”, which evaluates to False, and so we return None by default.

Let’s make our test more explicit, by saying that the response JSON will

be an empty dict:

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py (ch16l025).

deftest_returns_none_if_response_errors(self,mock_post):mock_post.return_value.ok=Falsemock_post.return_value.json.return_value={}user=self.backend.authenticate('an assertion')self.assertIsNone(user)

That gives:

if response.json()['status'] == 'okay': KeyError: 'status'

And we can fix it like this:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l026).

ifresponse.okandresponse.json()['status']=='okay':returnUser.objects.get(=response.json()['email'])

…

OK

Great! Our authenticate function is now working the way we want it to.

Creating a User if Necessary

Next we should check that, if our authenticate function has

a valid assertion from Persona, but we don’t have a user record for

that person in our database, we should create one. Here’s the test

for that:

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py (ch16l027).

deftest_creates_new_user_if_necessary_for_valid_assertion(self,mock_post):mock_post.return_value.json.return_value={'status':'okay','email':'a@b.com'}found_user=self.backend.authenticate('an assertion')new_user=User.objects.get(='a@b.com')self.assertEqual(found_user,new_user)

That fails in our application code when we try find an existing user with that email:

return User.objects.get(email=response.json()['email']) django.contrib.auth.models.DoesNotExist: User matching query does not exist.

So we add a try/except, returning an “empty” user at first:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l028).

ifresponse.okandresponse.json()['status']=='okay':try:returnUser.objects.get(=response.json()['email'])exceptUser.DoesNotExist:returnUser.objects.create()

And that fails, but this time it fails when the test tries to find the new user by email:

new_user = User.objects.get(email='a@b.com') django.contrib.auth.models.DoesNotExist: User matching query does not exist.

And so we fix it by assigning the correct email addresss:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l029).

ifresponse.okandresponse.json()['status']=='okay':=response.json()['email']try:returnUser.objects.get(=)exceptUser.DoesNotExist:returnUser.objects.create(=)

That gets us to passing tests:

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

Ran 9 tests in 0.019s

OKThe get_user Method

The next thing we have to build is a get_user method for our authentication

backend. This method’s job is to retrieve a user based on their email address,

or to return None if it can’t find one. (That last wasn’t well documented at

the time of writing, but that is the interface we have to comply with. See

the source for details.)

Here’s a couple of tests for those two requirements:

accounts/tests/test_authentication.py (ch16l030).

classGetUserTest(TestCase):deftest_gets_user_by_email(self):backend=PersonaAuthenticationBackend()other_user=User(='other@user.com')other_user.username='otheruser'other_user.save()desired_user=User.objects.create(='a@b.com')found_user=backend.get_user('a@b.com')self.assertEqual(found_user,desired_user)deftest_returns_none_if_no_user_with_that_email(self):backend=PersonaAuthenticationBackend()self.assertIsNone(backend.get_user('a@b.com'))

Here’s our first failure:

AttributeError: 'PersonaAuthenticationBackend' object has no attribute 'get_user'

Let’s create a placeholder one then:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l031).

classPersonaAuthenticationBackend(object):defauthenticate(self,assertion):[...]defget_user(self):pass

Now we get:

TypeError: get_user() takes 1 positional argument but 2 were given

So:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l032).

defget_user(self,):pass

Next:

self.assertEqual(found_user, desired_user) AssertionError: None != <User: >

And (step by step, just to see if our test fails the way we think it will):

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l033).

defget_user(self,):returnUser.objects.first()

That gets us past the first assertion, and onto

self.assertEqual(found_user, desired_user) AssertionError: <User: otheruser> != <User: >

And so we call get with the email as an argument:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l034).

defget_user(self,):returnUser.objects.get(=)

That gets us to passing tests:

Now our test for the None case fails:

ERROR: test_returns_none_if_no_user_with_that_email [...] django.contrib.auth.models.DoesNotExist: User matching query does not exist.

Which prompts us to finish the method like this:

accounts/authentication.py (ch16l035).

defget_user(self,):try:returnUser.objects.get(=)exceptUser.DoesNotExist:returnNone#

That gets us to passing tests:

OK

And we have a working authentication backend!

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

Ran 11 tests in 0.020s

OKA Minimal Custom User Model

Django’s built-in user model makes all sorts of assumptions about what information you want to track about users, from explicitly recording first name and last name, to forcing you to use a username. I’m a great believer in not storing information about users unless you absolutely must, so a user model that records an email address and nothing else sounds good to me!

accounts/tests/test_models.py.

fromdjango.testimportTestCasefromdjango.contrib.authimportget_user_modelUser=get_user_model()classUserModelTest(TestCase):deftest_user_is_valid_with_email_only(self):user=User(='a@b.com')user.full_clean()# should not raise

That gives us an expected failure:

django.core.exceptions.ValidationError: {'username': ['This field cannot be

blank.'], 'password': ['This field cannot be blank.']}Password? Username? Bah! How about this?

accounts/models.py.

fromdjango.dbimportmodelsclassUser(models.Model):=models.EmailField()

And we wire it up inside settings.py using a variable called

AUTH_USER_MODEL. While we’re at it, we’ll add our new authentication backend

too:

superlists/settings.py (ch16l039).

AUTH_USER_MODEL='accounts.User'AUTHENTICATION_BACKENDS=('accounts.authentication.PersonaAuthenticationBackend',)

The next error is a database error:

django.db.utils.OperationalError: no such table: accounts_user

That prompts us, as usual, to do a migration… When we try, Django complains that our custom user model is missing a couple of bits of metadata:

$ python3 manage.py makemigrations

Traceback (most recent call last):

[...]

if not isinstance(cls.REQUIRED_FIELDS, (list, tuple)):

AttributeError: type object 'User' has no attribute 'REQUIRED_FIELDS'Sigh. Come on, Django, it’s only got one field, you should be able to figure out the answers to these questions for yourself. Here you go:

accounts/models.py.

classUser(models.Model):=models.EmailField()REQUIRED_FIELDS=()

Next silly question?[32]

$ python3 manage.py makemigrations

[...]

AttributeError: type object 'User' has no attribute 'USERNAME_FIELD'So:

accounts/models.py.

classUser(models.Model):=models.EmailField()REQUIRED_FIELDS=()USERNAME_FIELD='email'

$ python3 manage.py makemigrations

System check identified some issues:

WARNINGS:

accounts.User: (auth.W004) 'User.email' is named as the 'USERNAME_FIELD', but

it is not unique.

HINT: Ensure that your authentication backend(s) can handle non-unique

usernames.

Migrations for 'accounts':

0001_initial.py:

- Create model UserLet’s hold that thought, and see if we can get the tests passing again.

A Slight Disappointment

Meanwhile, we have a couple of weird unexpected failures:

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

ERROR: test_gets_logged_in_session_if_authenticate_returns_a_user

[...]

ERROR: test_returns_OK_when_user_found

[...]

user.save(update_fields=['last_login'])

[...]

ValueError: The following fields do not exist in this model or are m2m fields:

last_loginIt looks like Django is going to insist on us having a last_login field on

our user model too. Oh well. My pristine, single-field user model is

despoiled. I still love it though.

accounts/models.py.

fromdjango.dbimportmodelsfromdjango.utilsimporttimezoneclassUser(models.Model):=models.EmailField()last_login=models.DateTimeField(default=timezone.now)REQUIRED_FIELDS=()USERNAME_FIELD='email'

We get another database error, so let’s clear down the migration and re-create it:

$ rm accounts/migrations/0001_initial.py $ python3 manage.py makemigrations System check identified some issues: [...] Migrations for 'accounts': 0001_initial.py: - Create model User

That gets the tests passing:

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

Ran 12 tests in 0.041s

OKTests as Documentation

Let’s go all the way and make the email field into the primary

key[33],

and thus implicitly remove the auto-generated id column.

Although that warning is probably enough of a justification to go ahead and make the change, it would be better to have a specific test:

accounts/tests/test_models.py (ch16l043).

deftest_email_is_primary_key(self):user=User()self.assertFalse(hasattr(user,'id'))

It’ll help us remember if we ever come back and look at the code again in future.

self.assertFalse(hasattr(user, 'id')) AssertionError: True is not false

Note

Your tests can be are a form of documentation for your code—they express what your requirements are of a particular class or function. Sometimes, if you forget why you’ve done something a particular way, going back and looking at the tests will give you the answer. That’s why it’s important to give your tests explicit, verbose method names.

And here’s the implementation (feel free to check what happens with

unique=True first):

accounts/models.py (ch16l044).

=models.EmailField(primary_key=True)

That works:

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

Ran 13 tests in 0.021s

OKOne final cleanup of migrations to make sure we’ve got everything there:

$ rm accounts/migrations/0001_initial.py $ python3 manage.py makemigrations Migrations for 'accounts': 0001_initial.py: - Create model User

No warnings now!

Users Are Authenticated

Our user model needs one last property before it’s complete: standard Django

users have an API which includes

several

methods, most of which we won’t need, but there is one that will come in

useful: .is_authenticated():

accounts/tests/test_models.py (ch16l045).

deftest_is_authenticated(self):user=User()self.assertTrue(user.is_authenticated())

Which gives:

AttributeError: 'User' object has no attribute 'is_authenticated'

And so, the ultra-simple:

accounts/models.py.

classUser(models.Model):=models.EmailField(primary_key=True)last_login=models.DateTimeField(default=timezone.now)REQUIRED_FIELDS=()USERNAME_FIELD='email'defis_authenticated(self):returnTrue

$ python3 manage.py test accounts

[...]

Ran 14 tests in 0.021s

OKThe Moment of Truth: Will the FT Pass?

I think we’re just about ready to try our functional test! Let’s just wire up our base template. Firstly, it needs to show a different message for logged-in and non-logged-in users:

lists/templates/base.html.

<navclass="navbar navbar-default"role="navigation"><aclass="navbar-brand"href="/">Superlists</a>{% if user.email %}<aclass="btn navbar-btn navbar-right"id="id_logout"href="#">Log out</a><spanclass="navbar-text navbar-right">Logged in as {{ user.email }}</span>{% else %}<aclass="btn navbar-btn navbar-right"id="id_login"href="#">Sign in</a>{% endif %}</nav>

Lovely. Then we wire up our various context variables for the call to

initialize:

lists/templates/base.html.

<script>/*global $, Superlists, navigator */$(document).ready(function(){varuser="{{ user.email }}"||null;vartoken="{{ csrf_token }}";varurls={login:"{% url 'persona_login' %}",logout:"TODO",};Superlists.Accounts.initialize(navigator,user,token,urls);});</script>

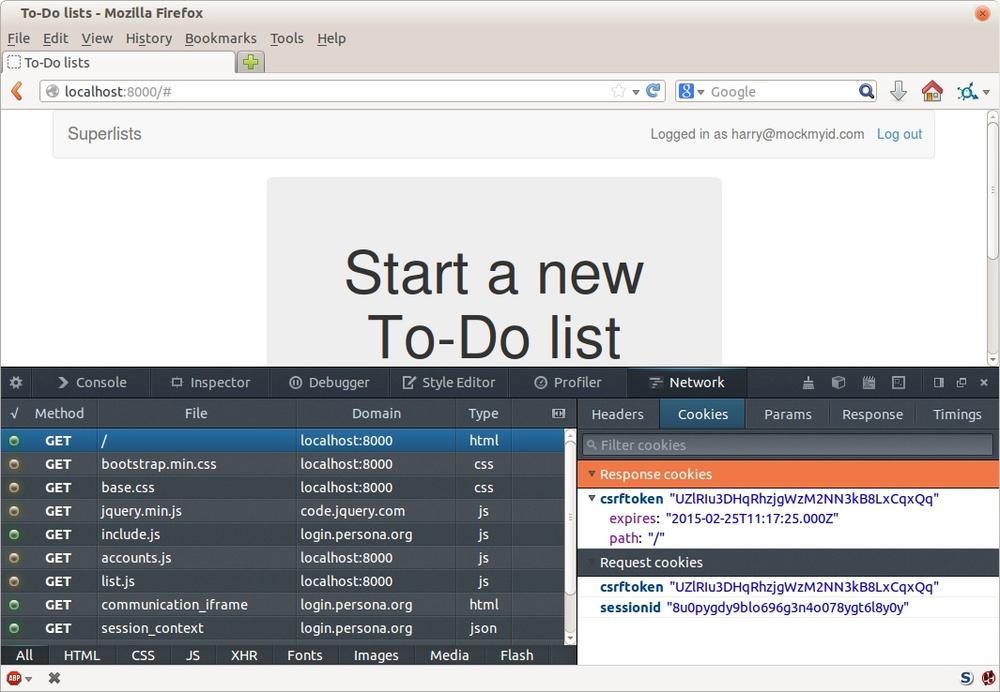

So how does our FT get along?

$ python3 manage.py test functional_tests.test_login

Creating test database for alias 'default'...

[...]

Ran 1 test in 26.382s

OKWoohoo!

I’ve been waiting to do a commit up until this moment, just to make sure everything works. At this point, you could make a series of separate commits—one for the login view, one for the auth backend, one for the user model, one for wiring up the template. Or you could decide that, since they’re all interrelated, and none will work without the others, you may as well just have one big commit:

$ git status $ git add . $ git diff --staged $ git commit -m "Custom Persona auth backend + custom user model"

Finishing Off Our FT, Testing Logout

We’ll extend our FT to check that the logged-in status persists, ie it’s not just something we set in JavaScript on the client side, but the server knows about it too and will maintain the logged-in state if she refreshes the page. We’ll also test that she can log out.

I started off writing code a bit like this:

functional_tests/test_login.py.

# Refreshing the page, she sees it's a real session login,# not just a one-off for that pageself.browser.refresh()self.wait_for_element_with_id('id_logout')navbar=self.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.navbar')self.assertIn('edith@mockmyid.com',navbar.text)

And, after four repetitions of very similar code, a couple of helper functions suggested themselves:

functional_tests/test_login.py (ch16l050).

defwait_to_be_logged_in(self):self.wait_for_element_with_id('id_logout')navbar=self.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.navbar')self.assertIn('edith@mockmyid.com',navbar.text)defwait_to_be_logged_out(self):self.wait_for_element_with_id('id_login')navbar=self.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.navbar')self.assertNotIn('edith@mockmyid.com',navbar.text)

And I extended the FT like this:

functional_tests/test_login.py (ch16l049).

[...]# The Persona window closesself.switch_to_new_window('To-Do')# She can see that she is logged inself.wait_to_be_logged_in()# Refreshing the page, she sees it's a real session login,# not just a one-off for that pageself.browser.refresh()self.wait_to_be_logged_in()# Terrified of this new feature, she reflexively clicks "logout"self.browser.find_element_by_id('id_logout').click()self.wait_to_be_logged_out()# The "logged out" status also persists after a refreshself.browser.refresh()self.wait_to_be_logged_out()

I also found that improving the failure message in the

wait_for_element_with_id function helped to see what was going on:

functional_tests/test_login.py.

defwait_for_element_with_id(self,element_id):WebDriverWait(self.browser,timeout=30).until(lambdab:b.find_element_by_id(element_id),'Could not find element with id {}. Page text was:\n{}'.format(element_id,self.browser.find_element_by_tag_name('body').text))

With that, we can see that the test is failing because the logout button doesn’t work:

$ python3 manage.py test functional_tests.test_login

File "/workspace/superlists/functional_tests/test_login.py", line 36, in

wait_to_be_logged_out

[...]

selenium.common.exceptions.TimeoutException: Message: Could not find element

with id id_login. Page text was:

Superlists

Log out

Logged in as edith@mockmyid.com

Start a new To-Do listImplementing a logout button is actually very simple: we can use Django’s built-in logout view, which clears down the user’s session and redirects them to a page of our choice:

accounts/urls.py.

fromdjango.contrib.auth.viewsimportlogout[...]urlpatterns=[url(r'^login$',views.persona_login,name='persona_login'),url(r'^logout$',logout,{'next_page':'/'},name='logout'),]

And in base.html, we just make the logout into a normal URL link:

lists/templates/base.html.

<aclass="btn navbar-btn navbar-right"id="id_logout"href="{% url 'logout' %}">Logout</a>

And that gets us a fully passing FT—indeed, a fully passing test suite:

$ python3 manage.py test functional_tests.test_login [...] OK $ python3 manage.py test [...] Ran 54 tests in 78.124s OK

Note

I’m actually glossing over a small problem here. You may notice, if you test the site manually, that Persona sometimes re-logs you in automatically after you hit logout. Many thanks to Daniel G who finally prompted me with a fix for this. You can find it here if you’re curious.

In the next chapter, we’ll start trying to put our login system to good use. In the meantime, do a commit, and enjoy this recap:

[29] If you’re using Python 3.2, upgrade! Or if you’re stuck with it,

pip3 install mock, and use from mock instead of from unittest.mock.

[30] Even though we’re going to define our own authenticate function,

we still import from django.contrib.auth. Django will dynamically replace

it with our function once we’ve configured it in settings.py. This has the

benefit that, if we later switch to a third-party library for our authenticate

function, our views.py doesn’t need to change.

[31] Actually, this is only happening because we’re using the patch

decorator, which returns a MagicMock, an even mockier version of mock that

can also behave like a dictionary. More info in the

docs.

[32] You might ask, if I think Django is so silly, why don’t I submit a pull request to fix it? Should be quite a simple fix. Well, I promise I will, as soon as I’ve finished writing the book. For now, snarky comments will have to suffice.

[33] Emails may not be the perfect primary key IRL. One reader, clearly deeply emotionally scarred, wrote me a tearful email about how much they’ve suffered for over a decade from trying to deal with the effects email primary keys, due to their making multi-user account management impossible. So, as ever, YMMV.

Get Test-Driven Development with Python now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.