Chapter 1. Testable JavaScript

Your ideas are unique; your code is not. Almost every industry has been completely revolutionized by machines; yet strangely, the computer science industry has not. Programmers are essentially doing the exact same things we have been doing for 40 years or so. We write code by hand, and that code gets compiled or interpreted and then executed. We look at the output and determine whether we need to go around again. This cycle of development has remained unchanged since the dawn of computer science. Our machines are orders of magnitude faster, RAM and secondary storage sizes are unimaginably large, and software has grown increasingly complex to take advantage of these developments. Yet we still write code by hand, one keystroke at a time. We still litter our code with “print” statements to figure out what is going on while it runs. Our development tools have indeed grown increasingly powerful, but with every hot new language, tooling starts all over again. The bottom line is that writing software remains an almost entirely manual process in a world of incredible automation, and most of that automation is due to the fruits of our software-writing labors. The very act of writing software one character at a time is the height of hypocrisy.

While the bulk of any code you write has been written before, either in the language you are currently using or in another one, every application is unique, even if yours is doing exactly the same thing as your competitor’s. Unique or not, to succeed the application must also work. It does not have to be beautiful. It does not have to be the absolute fastest, nor does it have to be the most feature-rich. But it does have to work.

Applications are, at their core, just message-passing systems with some input and output. The amount of complexity built on top of that standard idiom continues to increase. With the advent of JavaScript, we must apply the lessons learned not only from other languages, but also from JavaScript itself to make our code testable. As JavaScript applications grow in size, on both the client and the server, we must be extremely careful to apply the best practices and lessons learned by our forefathers and tweak them to fit well with JavaScript.

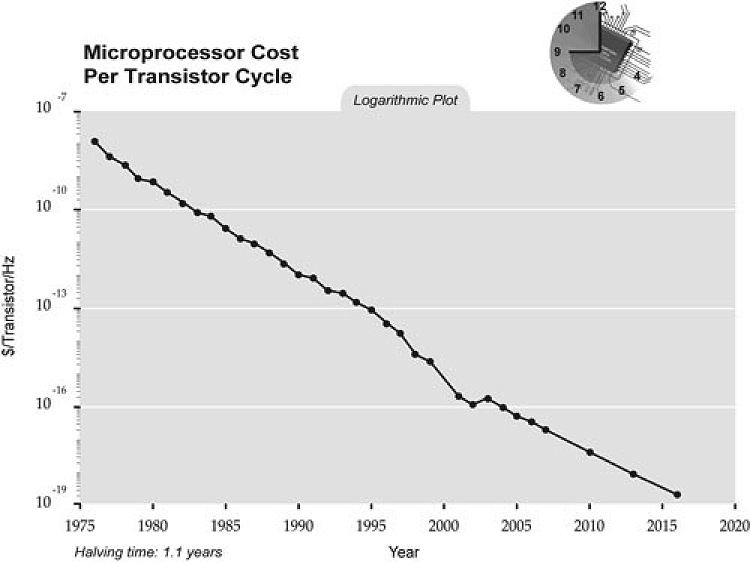

Figure 1-1 shows the microprocessor cost per transistor cycle over the course of three decades.[1] This ridiculous graph of cost per cycle of CPUs, following Moore’s law, keeps trending inexorably downward. Hardware refresh rate is indeed progressing far beyond anything seen in the software side of the world.

Enormous benefits have been achieved by programming machines to stamp out objects faster and smaller than ever before. In order to reach the incredible scale of global production, these rows of machines, assembled into factories, rely on standardization. Yet software engineers still sit in front of their individual computers, pecking away on their keyboards one character at a time.

Prior Art

While writing software is still an extremely manual process, there have been a lot of attempts to codify and standardize what developers should do to create a more repeatable process for writing “good” code. These processes, of course, hope to steer the wayward developer into writing “clean” and “bug-free” code. However, as with most things in life, “you gotta wanna”—and the results of employing any of the processes or methodologies covered in the following sections depend directly on the willingness of the developers to “buy in” to the system. The meat of this book is not about how or which methodology to use or choose, but what to do and think about when actually programming. Let’s run through some of the current thinking.

Agile Development

This is a big one that is a placeholder for a lot of practices. The Agile approach is mainly a response to the “waterfall” model of software application development that occurs using a serialized process of discrete stages. For example, first the specification is written, then coders code, then testers test, then the application is deployed, and then we go back to updating the specification for new features. Each step in the process happens serially and in isolation. So, while the specification is written, the coders and testers wait. While the coders code, the testers wait, while the testers test, everyone waits, and so on.

Agile development tries to be more flexible and allow each stage to occur in parallel. Software that works is the top priority. Instead of waiting around for large chunks of time for the previous step to be perfect before handoff, each team iterates over shorter cycles, so things are always happening. Big chunks of work get broken down into smaller chunks that can be more easily estimated. Agile seeks to break down the walls between each group in the development cycle so that they work together and therefore reduce the time between deliverables. Collaboration with customers helps to define the final deliverable.

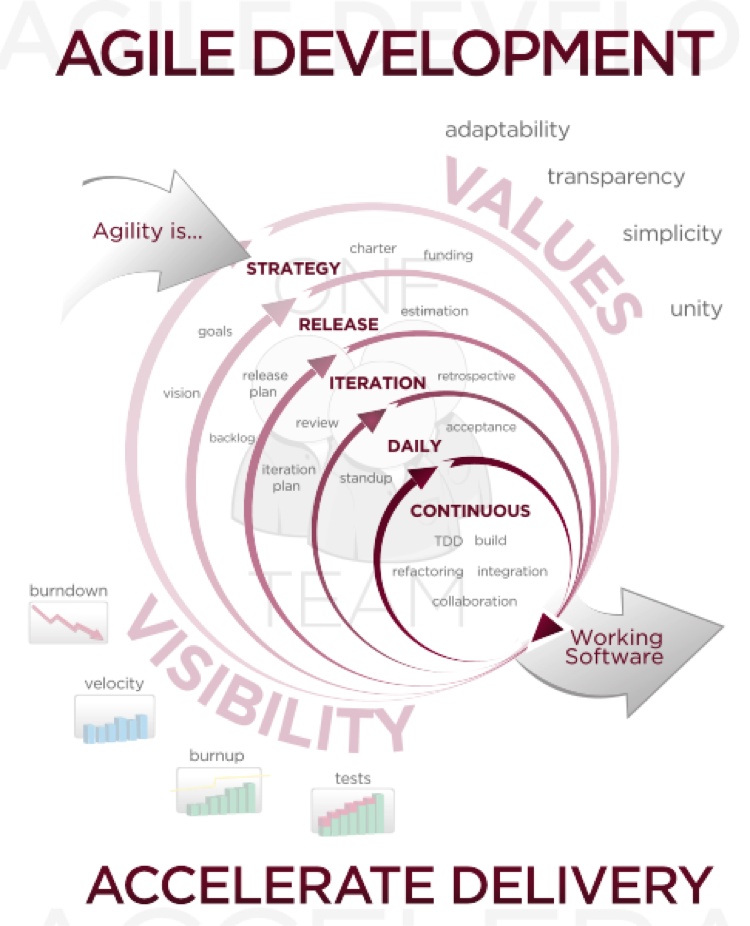

Note that the use of Agile methods does not necessarily mean your application is completed faster or with higher quality. Agile’s biggest strength is the way it deals with changes. In the waterfall model, any change would require running through the entire process all over again. Agile’s shorter cycles allow changes to be more easily incorporated into the final product. You might be using Agile already if you hear the words fail fast, release often, backlog, standup, or any phrase with the word continuous. Most modern development utilizes Agile to some extent. Figure 1-2 shows the canonical chart of the Agile development process.

There is a lot going on in Figure 1-2, but the basic idea is that quick iteration and constant interaction will accelerate the delivery of quality software.

Agile itself does not mandate how software is written; rather, it recommends several methodologies that fit well with the Agile philosophy. For example, “user stories” are plain sentences by “users” about what features they need from the application. These stories are ideally fed back into the product as feature requests for the application. A user is anyone who uses your application or API, from someone sitting at home to a developer in another group who can contribute to help define the feature set of the final application. Pair programming is another development methodology often associated with Agile. In its purest form, pair programming is two programmers sitting at the same desk, staring at the same monitor, with one keyboard and mouse, writing software together. While one programmer is typing, the other is actively debugging and thinking about the code. Two minds are typically better than one, so issues are found and resolved more quickly than if the two programmers were working in isolation.

Test-Driven Development

Test-driven development (TDD) is a recommended practice of Agile software development. TDD wants you to write your tests first, before you write any code. These tests provide the expectations to which your code must conform. After you write tests that fail (as there initially is no code to make the tests work), you then start writing code that makes your tests pass. As your tests stay one step ahead of your development, you will never have any code that is not covered by a test. That is the theory, at least. In reality, what tends to happen is developers start to go down this path and initial tests are written, but the code soon overtakes the tests. Hey, at least you got some tests out of the bargain!

TDD clearly works best when you are starting a new project or module. It is also most successful if only unit tests are required. Writing full integration tests before any code exists is daunting! TDD also provides a great reason/excuse to rewrite existing legacy code. If a developer’s choice is “write a bunch of tests for already existing code” or “write your own new code starting with tests,” most likely the developer will choose the latter option. Of course, developers do not always have a choice; just do not expect happy faces and high fives from them if writing tests for an already existing codebase is the path chosen to move forward.

Regardless, TDD is not a bad thing; in fact, it can be a very good thing. TDD is great at beginnings, whether an entire application or a single module—everyone is excited to write new code, and if the “cost” of writing that new code is writing tests first, so be it. And as there is no code at the beginning, the “cost” of writing tests is minimal.

An interesting study in 2005 on Canadian undergraduates found that TDD made programmers more productive because they wrote more tests. While that is debatable, what is more interesting is that the researchers “also observed that the minimum quality increased linearly with the number of programmer tests, independent of the development strategy employed.”[2] It is good to know that the number of tests is proportional to higher code quality. The conclusion one could draw is that any methodology that gets developers to write more tests before, during, or after coding is a very good thing.

Behavior-Driven Development

Behavior-driven development (BDD) builds on TDD to provide developers and non-developers a common language to

describe correct application and module behavior. The common language is just your everyday

language. For example, instead of writing a test called testEmptyCart, you would provide a description that defines the behavior of the

module under test, such as “the shopping cart should not allow you to check out if it is

empty.” Using a common language to define tests or expectations allows anyone to more easily

understand what is being tested, as well as helping to define what the tests and

expectations should be.

BDD utilizes Agile user stories to define tests against the code. The user stories can then be directly translated into tests. The user stories typically must follow a specific template of the form: As a [someone] I want to [something] so that [result].

Each blank is filled in appropriately, as in a Yahoo! Mail user I want to attach a picture to my email so that my recipients can see it. This user story can then be translated into a set of feature requirements and tests for the Yahoo! Mail product.

BDD is great for formalized feedback from people not on your team (technical or not), to help you understand how your system should operate. The user stories can usually be directly translated into tests—and anything that promotes focused testing (and more of it) is a very good thing!

The Best Approach?

This book is intended to neither advocate nor explicate any development methodology, and by that measure I think it succeeds admirably. Waterfall, spiral, Agile, and other methodologies are all well and good, but none necessarily leads to testable code, let alone testable JavaScript. Similarly, TDD, BDD, and other forms of development also do not necessarily lead to testable JavaScript. What does lead to testable JavaScript? A commitment to writing clear, loosely coupled, and well-commented code that you know will be maintained by someone else will lead to testable JavaScript. Writing, reading, and maintaining testable JavaScript does not require test-driven, behavior-driven, or any other “-driven” development practices. However, following any practice that emphasizes tests along with code is a good thing. The most important thing to internalize is that the code you write does not exist in a vacuum. Any code you write professionally will be looked at, compiled, debugged, and finally used by not only yourself, but hopefully someone else too. In the end, you are writing code for other people to maintain, study, and use.

Code Is for People

This has been beaten into our heads a lot lately, and I am not going to let up on that trend! The code we write is not for computers, it is for people. Writing software is a hands-on business. Computers just want the bits; JavaScript, C++, Java, Perl, Lisp, or whatever else all gets compiled down to the CPU’s extremely limited instruction set. The CPU does not know if it is running a “compiled” or “interpreted” language. The CPU does not care about comments or semicolons or whitespace. The CPU is blissfully unaware of the structure, syntax, or semantics of any of the myriad computer programming languages people use. A JavaScript program looks just like a C++ program, which looks exactly like a Perl program to the CPU.

At the lowest level, the success or failure of our programs is intertwined with the machine language code that the CPU executes; but we rarely, if ever, see that. We see only the original code. The CPU does not care what you are trying to do, but people do.

Software starts with intent. What are you trying to do? What is this piece of code trying to accomplish? Why are you writing it? These are important questions that either you or your coworkers must ask every day. You transform that initial intent (the “whats” and the “whys”) into actual code: the “hows.” This book is mostly concerned with the “hows.” Figuring out what you are trying to do and why you are trying to do it are the necessary first steps toward getting to the “how” part of your job, but the rubber really hits the road when you are actually dealing with the “hows.” Books on programming languages help with the lowest-level “how”; then software-pattern books go one layer higher. This book hopes to clearly explain the top layer of the “how” totem pole: “how” to write testable code and “how” to test it.

But before we can get to the “how,” it is important to understand the “what” and the “why” of software development.

Why do we want to write testable code? What is testable code?

Why

“Writing software is the hardest thing people do,” says Douglas Crockford, which means it is extremely important that software be as human-friendly as possible. Testable code is easier to test, which means it is easier to maintain, which means it is easier for people (yourself included) to understand it, which makes it easier to maintain, which in turn makes it easier to test.

We have gone in a circle, but it is a virtuous circle. There is no Platonic ideal of perfect code; testability, maintainability, and understandability are interlocked, and there are lots of opinions about what these things are and how to get there with software. However, finding and fixing bugs is much simpler with testable, maintainable, and understandable code. And you as a programmer will spend at least half of your time finding and fixing bugs, either in your code or in someone else’s, so be nice to yourself and try to make that time as pleasant as possible.

Why testable

Testing code, using any kind of testing, is a required activity. Either you test it or someone else does, even if it is the end user simply using your application. Nothing is perfect the first time, or any subsequent time thereafter. Even one of the simplest JavaScript programs:

x = x + 1;

can have problems. What if x

is a string? What if x is infinity?

What if x is an object? As our

programs get more complicated, we can only hope to test the most

common paths for sanity. Exhaustive testing is impossible. Writing

code that is easy to test, or “testable,” at least gives testers a

fighting chance to accomplish the most basic and hopefully ever-more

advanced testing.

Why maintainable

Programmers do not always write code from scratch. Sometimes we are tasked with debugging and maintaining someone else’s code. That someone else may be long gone, just as you are long gone from the code you wrote at your previous company. While you are maintaining someone else’s code, someone else is maintaining yours. Besides making the world a better place, code that is testable is also more “maintainable.” Usually you do not have a full picture of what your changes will affect, and having tests, made possible by testable code, can help you figure out the extent and ramifications of your seemingly little changes. When you know how the code works—specifically, what will happen when you make changes to it—you have maintainable code. This is code you are not afraid of. This is code that you can more easily share with members of your team. This is code that does not need to be rewritten solely to understand it. As an application increases in size, the number of people with full knowledge of the code dwindles rapidly. Even these people can be surprised that a seemingly innocuous change has affected functionality elsewhere.

Why understandable

The third feature of quality software, which is intertwined with the other two, is the ability to look at code and understand it. How long does it take when staring at a piece of code to understand what it does? Clearly, being able to test it (and have tests for it) goes a long way toward helping you understand what the code is doing. But can you look at a method or function and understand not only the author’s intent but also the “how”? If you cannot understand either code you wrote six months ago or code someone else wrote, you have a serious problem. Looking at a piece of code and understanding it is not only satisfying, but also necessary to properly fulfill your job requirements. Conversely, if you have written code that you no longer understand, you have failed. Code is for people to understand, maintain, and test. You write code for other people, which means your peers must be able to relatively quickly understand your code. If code is not understood, it can be neither tested nor maintained. In those circumstances, code typically gets completely rewritten. You may be throwing out crap or you may be throwing out awesome code that is 99% bug-free, but how could anyone ever know that? If it is not testable, maintainable, and understandable, it is trash.

What

So “what” exactly is “testable” code? What does “maintainable” code look like? What kind of code is “understandable” code? Let us dig a bit deeper into those questions. We will see numerous examples of “what” all of this looks like throughout this book.

What is testable

Testable code is code that is easy to test. Bet you didn’t see that coming! But what makes code easy to test? In general, the features that make code easy to test are the same ones that make it easy to maintain, and more understandable: there’s less of it, and it’s less complex code, fully commented, and loosely coupled. These features and more make code “testable.” By exploiting testability features and using tools focused on testing, you make your code more and more testable.

What is maintainable

Maintainable code is code that can be handed over to other team members and peers with a minimum of handholding and transition. Code that is testable with good tests and is understandable is more maintainable than complex, uncommented code without tests. Maintainable code can live a full product life cycle: it does not need to be rewritten, either partially or fully, when passed off from person to person. Code that you can fix and change, without having to fully understand everything the code does but with the confidence that your changes have not broken something else, is maintainable code.

What is understandable

How long will it take when looking at a piece of code—either a function or an even smaller piece—for you to understand it? Does the original author need to explain it to you step by step? Or can you “get” it yourself in a reasonable amount of time? Simple, small, and commented code tends to be more understandable. Being able to test your assumptions about the code by running it in isolation also helps greatly in terms of understanding. It is vitally important that code is understandable; otherwise, it will be thrown away and rewritten.

How

Understanding the “why” and the “what” leads us to the “how.” This book is primarily concerned with how you can write, test, and maintain testable, maintainable, and understandable code. Clearly, testing and maintaining code that is already testable, maintainable, and understandable will make your job easier. Starting with this solid foundation will make you much more productive, and productive people are happy people, and happy people are productive people! It’s one of those virtuous circles again. I like virtuous circles.

How testable

Writing testable code is easier when you start with a blank slate (isn’t everything easier when you start with a blank slate?). Some development methodologies, such as TDD and BDD, can lead to testable code, but not necessarily. This is because having tests for code does not automatically make that code testable. However, when you think about testing from the start, your code typically will end up more testable than code written from scratch without regard to testing. I do not demand that you use TDD or BDD when writing code; however, I think it is a great idea to start with testing in mind, and I believe that testing constantly is necessary to writing testable code. Writing tests or the UI first is not a requirement for testable code, but writing unit tests first (TDD) or integration tests first (BDD) speaks to a fundamental notion of testable code: the sooner the code can be executed and tested, the better. I would like to squeeze a third approach in between TDD and BDD: test-while-driven development (TWDD). The tests and the code are in a chicken-and-egg situation: either one can come first, as long as the other comes immediately afterward—meaning, do not write a lot of tests and no code, and do not write a lot of code and no tests. Instead, write a little code and then quickly write a little test. Or perhaps write a little test and then write a little code.

Again, this does not necessarily lead to testable code. You can still write crap with a lot of tests. While you are writing little bits of code and little tests, remember the bigger picture: write small, isolatable chunks of code with minimal dependencies and minimal complexity. That mindset is the essence of this book.

How maintainable

You can achieve maintainable code in much the same way you achieve testable code: by writing small bits of simple, isolatable code—small because the fewer the lines of code, the fewer the bugs; simple because simple code is easier to maintain; and isolatable so that changes made to the code will affect as few other pieces of the code as possible. We will investigate several methods for keeping your code small and isolated throughout this book.

How understandable

Not surprisingly, writing understandable code follows the same principles. Simple code is more quickly understood. Having tests along with the code gives further insight into the intent and inner workings of the code. Comments greatly aid in understandability.

Writing code is similar to composing chapters in a novel: several small chapters are easier to understand than a few large ones. Being verbose in both comments (inserting comment blocks before methods) and code (choosing meaningful variable names, following best practices, following a consistent coding style, etc.) enhances understandability. Your peers tasked with maintaining your code are not morons. Give them some signposts to aid in their understanding, and your code will not have to be thrown away and rewritten.

Beyond Application Code

Your job does not end with writing small chunks of testable code. You also get to test it! Writing testable code makes testing it, and finding bugs within it, much easier. No developer wants to attempt to debug a giant mound of code, especially if said developer did not write it.

Testing

Unit tests are a developer’s first line of defense. Not only do unit tests force you, the developer, to understand your code, but they also help you to document and debug your code. Beyond unit testing, integration testing helps to ensure that everything is working together as planned—especially client-side JavaScript, which runs on many different browsers on an increasing number of platforms (desktops, tablets, and phones). Finally, performance testing and load testing help to ensure that your application is performing to specification. Each step up the testing ladder exercises your code at different levels of abstraction. Each test type finds bugs in different usage scenarios. Fully testing code requires tests at all levels of abstraction. And still you will have bugs in production; there is no magic bullet.

Debugging

Regardless of the number of tests you conduct, debugging is a fact of life for software developers. Fortunately, JavaScript has some very nice tools that are constantly improving to help. Leveraging these tools will help make your debugging life easier, which is nice, as you will probably spend much more time debugging your code than writing it.

Whether you are debugging locally or remotely, many powerful tools are available for step-by-step debugging and resource management.

Recap

Testable JavaScript does not automatically flow from Agile, waterfall, TDD, BDD, or whatever other software development philosophy you might follow. Testable JavaScript is a commitment to small, loosely coupled, bite-sized chunks of simple code. How you arrive at that code is up to you. This book will hopefully provide insight into achieving this state of coded bliss.

Writing testable code will make your life, and the lives of all who follow you, much easier. From fewer bugs to more easily fixed ones, from easier testing to simpler debugging, testable JavaScript is your gateway to sanity.

Most importantly, do not forget that you are writing code for people, not for the compiler. People, yourself included, will have to maintain your code going forward, so make everyone’s life easier, including your own, and write testable JavaScript.

[1] By Wgsimon [own work: CC-BY-SA-3.0].

[2] Erdogmus, Hakan, Marco Torchiano, and Maurizio Morisio. January 2005. “On the Effectiveness of the Test-First Approach to Programming.” Proceedings of the IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 31(3): pp 226-237; NRC 47445.

Get Testable JavaScript now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.