Chapter 1. Lessons from Obesity

“What we know about diets hasn’t changed. It still makes sense to eat lots of fruits and vegetables, balance calories from other foods, and keep calories under control. That, however, does not make front-page news.”

William Banting learned the hard way that you are what you eat, and as a result, he invented what we know today as the modern diet.

An undertaker from Great Britain, Banting found himself suffering from “failing sight and hearing, an umbilical rupture requiring a truss, and bandages for weak knees and ankles.” He reported not being able to walk down stairs without help, or to touch his toes. He went to see many doctors for his various conditions but claimed that, “not one of them pointed out the real cause of my sufferings, nor proposed any effectual remedy.” The real cause of Banting’s suffering wasn’t that he couldn’t walk down stairs, it was that he was obese.

After he started losing his hearing, he finally sought specialized medical attention and found himself in the care of “the celebrated aurist” Dr. William Harvey. The physician put him on a diet inspired by a lecture he’d heard about treating diabetes: five to six ounces of meat or fish three times a day, accompanied by stale toast with cooked fruit. Beer, potatoes, milk, and sweets were not allowed. Alcohol was, though: four to five glasses of wine a day, a glass of brandy in the evening, and sometimes even a wake-up cocktail in the morning were called for.

Banting reported losing 13 inches off his waist and 50 pounds of weight over the course of a couple of years. It was only then that Banting realized that he had been treating symptoms, not the root cause. Once he fixed his diet, his other problems went away. He could walk down the stairs again.

We’ve known that obesity is bad for a very long time. In the fourth century BCE, Hippocrates, called the father of medicine by Western scholars, wrote, “Corpulence is not only a disease itself, but the harbinger of others.” And the Bible is filled with warnings about overconsumption. Proverbs 23:20–21 says, “Be not among winebibbers; among riotous eaters of flesh: For the drunkard and the glutton shall come to poverty: and drowsiness shall clothe a man with rags.”

However, for thousands of years, obesity was usually a disease affecting only the most affluent. Food—especially the delicious, calorie-dense stuff—was simply too expensive for the average person to obtain. Few could afford to be fat, and thus being so was often considered a way to display one’s prosperity.

Then a great technological shift happened, much like the one that we faced in the second half of the twentieth century. New technology and new techniques increased our food supply. The steam engine, crop rotation, and the iron plow revolutionized agriculture in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries, alongside a variety of sociopolitical changes, including the rise of the merchant class. The food supply became more abundant, and access to it improved. Obesity was no longer just for a fortunate few.

It was in this context that Banting decided to share his results with the world. In 1863, he published Europe’s first modern diet book, Letter on Corpulence, and sold an astounding 63,000 copies for a shilling each. It was the first diet craze of the West (called, appropriately, banting), and thousands were inspired to lose weight with his diet. The book also had global reach. It was translated into multiple languages and according to Banting, achieved good sales in France, Germany, and the United States.

The medical community treated it as old news. Their critique wasn’t an assault on the idea, but they questioned why Banting’s letter was so popular in the first place. Similar works had been published prior to his, but they were written by physicians, for physicians. Letter on Corpulence was written by a suffering person, for suffering people. His message resonated. People were ready to hear it. And Banting provided it in a form they could understand.

In the fourth edition of his letter, Banting spends upwards of seven pages defending himself against a medical fraternity that disputed his story, claiming that he must not have sought the attention of particularly good doctors if it took him that long to get well, or worse, that Banting’s recommendation of four meals a day would cause more corpulence. His response:

“My unpretending letter on Corpulence has at least brought all these facts to the surface for public examination, and they have thereby had already a great share of attention, and will doubtless receive much more until the system is thoroughly understood and properly appreciated by every thinking man and woman in the civilized world.”

A Modern Epidemic

Banting was right about all the public attention—the commercial success of his pamphlet helped create an industry of diet books, coaches, and consultants. His documents are preserved online by the Atkins Foundation, the organization dedicated to Robert Atkins, who would come along more than a century later and encourage people to go on a very similar low-carbohydrate program.

But neither Banting nor Atkins, nor any of the thousands of others, solved the problem of obesity. In recent years, it has run rampant through America.

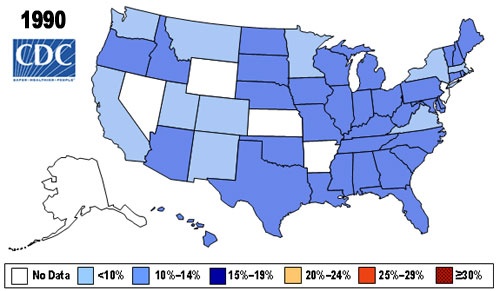

The Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta provides annual data on a state-by-state basis regarding our obesity epidemic. Figure 1-1 shows what obesity looked like in 1990.

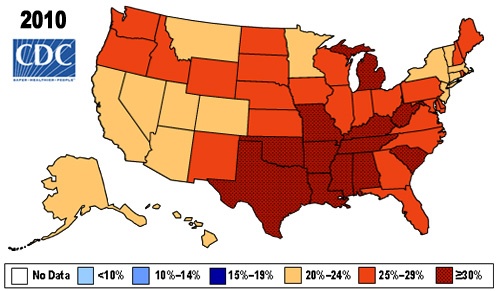

While the CDC does not have data for five states in 1990, none of the states for which data was collected had obesity percentages higher than 14%. Figure 1-2 shows what that same map looks like with data from 2010.

In 20 years, we went from an obesity rate no higher than 14% in any state to an obesity rate no lower than 20% in any state, and an obesity rate higher than 25% in most states. Twelve states—Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia—now have obesity rates greater than 30%. Moreover, our obesity rate is accelerating; we’re getting fatter faster than we were 20 years ago.

What has happened?

The same things that have always happened. Food is cheaper. We can afford more of it. And we increased the number of steps between our food’s source and our bellies so much so that our food doesn’t even look like food anymore.

To start with, calorie-dense foods are now less expensive and more readily available than ever. According to the USDA, we’re now producing 3,800 calories per person per day. That number is an increase of several hundred calories since 1970. And accordingly, 62% of adult Americans are now overweight, according to the National Center for Health statistics—in 1980, that number was 46%.[3]

The Birth of Industrial Agriculture

In the twentieth century, agriculture went through profound changes, both in the United States and globally. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the rural farmer was the largest demographic in the United States. Nearly a century ago, more than 50% of the United States population lived in rural areas, and farming represented 41% of the American workforce.[4]

Then, industrialization happened. The development of the Ford Model-T, the tractor, pesticides, and other agricultural technologies brought a new drive for efficiency into America’s heartland.

It took a century to double food production from 1820 levels to those in 1920. It took just 30 years to double it again, between 1920 and 1950. It took 15 years from 1950 to 1965, and 10 between 1965 and 1975. Food production has continued to grow exponentially as science and the demand for food has caused our agricultural industry to industrialize.[5]

In the words of food activist Michael Pollan:

“In the past century American farmers were given the assignment to produce lots of calories cheaply, and they did. They became the most productive humans on earth. A single farmer in Iowa could feed 150 of his neighbors. That is a true modern miracle.”[6]

This drive and industrialization is necessary, actually. By 2050, the UN estimates, we’ll need to double our food production again to maintain projected population growth.[7]

The miracle of abundance comes with a remarkable set of consequences. Today, America’s heartland is empty; only 17% of Americans live in rural communities. Efficiency also means fewer jobs: if a single farmer can feed 150 neighbors, it means you need fewer farmers. Today, less than 2% of the United States population is directly employed in agriculture.

Another significant consequence of industrialization is a rise in occupational health hazards. Agriculture is now one of the most dangerous professions in America. According to the Centers for Disease Control,[8] agriculture is dominated by giant factory farms with livestock packed at huge scale. It’s what allows just four companies to produce 81% of the cows, 73% of the sheep, 57% of the pigs, and 50% of the chickens in America.[9] But with a relatively homogenized and industrialized production system, toxins travel faster in our food supply and affect more people. Packing animals in makes them more susceptible to disease, which means that more antibiotics and other drugs go into our livestock, decreasing their effectiveness for treating human diseases. And locating these farms near places where produce is grown means an increased risk of food contamination.

While calories have become more affordable, the nutrients in our food have slowly disappeared before our eyes, only to be replaced with corn-based sugar, soy-based fat and protein, and a whole lot of salt. Sugar, corn, and soy are the three crops of America, and they are the crops that make it into our animals and onto our dinner tables. Our grocery stores are full of manufactured foods, made mostly from corn and soy, that aren’t particularly good for us and as Michael Pollan says, not something that your grandmother would recognize as food.

We don’t grow our food anymore; we manufacture it. And in the 1970s, we eliminated requirements for calling artificial food “artificial.” So right on the front of the packages, in really big emotion-grabbing type, companies could create exciting new forms of false food without ever saying so. Add to that the fact that this cheaper, more highly processed food alters our taste sensation so that the organic stuff seems bland, and it’s easy to see why we’ve gotten obese. Figures 2-1 and 2-2 speak for themselves.

A New Set of Consequences

As probability would have it, I am one of the 62% of Americans considered overweight. In fact, according to my Body Mass Index (BMI), I’m one of the 27% of us considered obese. It’s a terrible feeling, compounded by my constant attempts at exercise. I’ve run a marathon and several half marathons; gone through the constant physical, mental, and intellectual abuse of Tony Horton’s P90x; and endured the torture of vinyasa yoga. My house is littered with high-tech gadgetry—from the Wii Fit to the Withings Internet-powered scale (it posts your weight on Twitter) to the FitBit (a little gadget you wear on your belt to tell you how many calories you’ve burned by walking around). I do all of this for two reasons: so that I don’t need to grease the doorframes to get out of the house, and so that I can eat.

If you want to know why Americans are getting fat, ask a fat person. It’s because for most of us, food—especially food that’s bad for us—is delicious.

Let’s be clear: a chocolate-chip cookie, for most people, is superior in every way to a head of lettuce, and if one could make a chocolate-chip cookie as good for you as a pile of spinach, the salad industry would be in danger of being obliterated by Mrs. Fields. It’s a cruel joke that the stuff that tastes the best is often the stuff that’s worst for us. But the reason behind it makes a lot of sense.

From way back during mankind’s foraging days until just a few centuries ago (less than a blink through the eyes of human history), we didn’t have a lot of food to go around. We never knew where our next meal would come from, and thus our bodies became wired for scarcity. Over the millennia, we evolved into energy conservation machines. It’s why we crave that salt-fat-sugar combination—and why, as far as I’m personally concerned, the most dangerous place in America is between me and a chicken wing.

Our bodies are programmed to acquire as many resources as possible, and to take what we don’t need and store it as fat—fat that will keep us warm and supply us with energy during the harsh winter when there’s a lot less out there to eat.

For modern society, neither winter nor famine is the same threat they used to be. Not only can you get “fresh” tomatoes at your grocery store in the middle of winter in the coldest regions of America, the season has all but stopped killing us. In 2010, according to the U.S. Natural Hazard Statistics report, there were only 42 deaths from “winter” in the United States and another 34 from cold. You have about as much chance of dying from the cold as you do from lightning.[10]

The fresh, warm Krispy Kreme donut on a cool fall morning does more than treat (and trick) the tastebuds. That sort of food production allows the planet to sustain ever-larger populations—we’ve now surpassed seven billion human beings—with cheap calories.

Once the biggest threats America faced were the Famed Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—war, famine, pestilence, and disease. But we’ve traded them in for a new killer. Today, 13.5 million[11] people die each year of heart disease and stroke, and 4 million from diabetes-related complications[12]—far more than die in automobile accidents. Heart disease is now our number one killer, and it takes more people to the grave in the United States in five years than all our war-related deaths combined. Instead of dying from the cold of winter, we find death in cholesterol.

The Modern Diet

Today, nearly a century and a half after Banting’s diet recommendations, Amazon.com lists nearly 20,000 books available for purchase on diets.

As of this writing, 681 books have been released in the past 30 days, with another 112 coming soon. In the first six months of 2011, more than 2,000 books on weight-loss were released.

We know beyond any scientific doubt that being fat kills. For more than a century and a half, the medical community has known that sugars and carbohydrates make us fat. But we keep eating, despite all of the information and transparency—from this month’s 681 diet books, to the nutritional labels on every item in the grocery store, to chains of Weight Watchers and Jenny Craigs across the country.

Food’s scrumptious properties aside, perhaps the diet books have something to do with our obesity problem. It certainly seems as though the number of diet books available to the public correlates to obesity rates. While any economist would predict that the number of books to help people be less fat would grow with the number of fat people in the market, at what point does causation flow the other way around? Maybe all these diet books are making us fat by making it harder to figure out what a healthy diet is. At the very least, the modern obsession with weight over diet brings us a significant health issue. Imagery of being perfectly shaped and skinny trumps being healthy and happy, and as a result, scores of people suffer— and die—from eating disorders.

No matter which way you turn, abundant information makes it easy to distort our relationship with food into something unhealthy. If you’re looking to surf through a land of false promises, spend a few minutes in the diet aisle of your local bookstore. You can lose weight by thinking like either a caveman or a French woman, or by eating only food that’s cooked slowly. You can lose it, says the updated 2012 edition of Eat This Not That! (Rodale Books), by simply swapping in a Big Mac® for a Whopper-with-cheese®.

In the diet aisle, our relationship to food can take on social, political, and environmental significance. A healthy diet mustn’t just include the right number of calories and the right interaction of nutritional elements. It must also produce the least amount of carbon, and be as natural as possible. It’s no longer good enough to eat reasonable portions of lean meat; the meat must come from a cow that could roam free and eat grass.

If time is of the essence, you can get top-selling weight loss books promising change based on your lifestyle: just spend 8 minutes (Eight Minutes in the Morning, Harper), 4 hours (The Four Hour Body, Crown Archetype), or 17 days (The Seventeen Day Diet, Free Press). If religion or the supernatural is your thing, just look to the 159 diet books available containing the word “miracle.”

Most of what these books cover and the pseudoscience behind them appeals to the same emotional impulses as do the people peddling calories in the first place. Some of this is unavoidable in a free society: the right answers— healthy information—compete side-by-side with the answers we may want to hear but which may not be true. Only the highly nutritionally literate can easily tell the difference.

The best food journalists distill this complex world of choices into healthy ones. Michael Pollan, Knight Professor at the University of California at Berkeley, is a leading example. The beginning of his In Defense of Food (Penguin) is a seven-word diet guide: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” And there it is, right up front. We can take those three simple rules—those seven words—into the grocery store, and win.

While our collective sweet tooth used to serve us well, in the land of abundance it’s killing us. As it turns out, the same thing has happened with information. The economics of news have changed and shifted, and we’ve moved from a land of scarcity into a land of abundance. And though we are wired to consume—it’s been a key to our survival—our sweet tooth for information is no longer serving us well. Surprisingly, it too is killing us.

[2] http://www.althealth.co.uk/news/latest-news/diet-study-confusion-will-not-change-habits-analysts/

[5] Scully, Matthew. Dominion (p. 29). St. Martin’s Griffin: 2003.

[9] Testimony by Leland Swenson, president of the U.S. National Farmers’ Union, before the House Judiciary Committee, September 12, 2000.

Get The Information Diet now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.