Introduction

You think you feel overwhelmed by the march of technology? Then how’d you like to be the lady who, one day in the mid-90s, entered a computer store, handed the salesman a blank floppy disk, and asked him if she could please have a copy of the Internet?

The funny thing is, in the mid-90s, you practically could fit the Internet on a floppy. It was a novelty then, a toy for computer scientists and power nerds. People didn’t have Web addresses on their business cards, didn’t buy stuff electronically, didn’t have PTA meetings about keeping their kids safe online.

Nowadays, the Internet is a different story.

Physically, the Internet is a very long series of wires (with wireless gaps here and there) that eventually connects everyone’s computer to everyone else’s.

Culturally, though, it’s as important a communications system as the telephone—maybe more important. It’s a critical piece of every business’s business. It gives a global voice to anyone with something to say—for free. It’s changing the way we use and do just about everything: relationships, politics, religion, war, radio, TV and movies, news, communications…. In fact, it might be easier to make a list of things that haven’t been changed by the Internet.

Unfortunately, the Internet is also a playground for the latest generation of electronic pickpockets, scam artists, and hate-mongers.

And the Internet isn’t finished growing up, either. Every year there are new developments.

For example, in 2004, you might have said that the two most important Internet technologies were email and the World Wide Web. Today, you’d have to mention stuff like RSS newsfeeds, free phone calls, podcasts, and blogs. (If any of these terms are unfamiliar, well, you’re reading the right book.)

About This Book

The thing about the Internet, though, is that nobody runs it. Oh, certain government and university bodies are there to fine-tune the technical protocols, but nobody owns the Internet; nobody’s in charge. There’s no 800 number to call for help. (Can’t you just see it? “Thank you for calling The Internet. Please hold; your call is very important to us.”)

And goodness knows there’s no user manual for it.

So how are you supposed to figure out how to get online? And how are you supposed to know what to do once you’re there?

The answers Internet veterans give you aren’t very reassuring. “Oh, you’ll figure it out,” they say. “Just keep clicking around till you find the good stuff.”

But your time is too important for that. And so, ladies and gentlemen, here it is, right in your hands: a user’s guide to the Internet.

This book is designed to answer all of the critical questions you might have about the Net, including:

How do I get on the Internet? (Hint: Not by taking a blank disk to the computer store.)

All kinds of gadgets can connect to the Internet these days: cellphones, settop TV boxes, pocket music players, and so on. But what most people connect to the Internet is a computer, and that’s what this book is all about. In Chapter 1, you can find out about the three most attractive ways to connect your Macintosh or Windows PC to the Internet—and how to do it yourself.

What do I do once I’m online? The Internet isn’t any one product or service; remember, it’s just a network of connections between computers. Specialized software programs can communicate over this digital pipeline in all kinds of interesting ways. This book covers them all.

For example, you’ve probably heard of email—the electronic version of postal mail. The World Wide Web is also deservedly famous (billions upon billions of “pages” displaying text and pictures that serve as ads, brochures, discussion groups, information flyers, and so on). But some of the up-and-coming technologies are even more intriguing. Young people use chat programs daily—like a typed version of CB radio—to carry on conversations, send pictures and music back and forth, and so on.

Other specialized programs let you make free “phone calls” across the Internet, computer to computer, using a microphone and speakers—and if you have a fast Internet connection, you can make video calls with these programs. Then there are blogs (Web logs, or daily opinion journals) to read. And podcasts (amateur radio and TV shows) to listen to or watch. All of this, by the way, is free.

What’s out there? Any 10-year-old next-door neighbor can get your computer hooked up to the Internet. But the meat of this book—its real value—is its tour of the Web. This is the information it takes years to pick up on your own—years of trial and error, painful experience, and barking up wrong trees.

Here, in one tidy atlas of the Web, is a summary of the very best ways to find stuff on the Web; do research; shop; manage stocks and finances; make travel reservations; play games and place bets; find and buy music, movies, and TV; post digital photos (or look at other people’s); find love on the world’s biggest personal-ad matchmaking services; and much more.

How do I get represented? For years, the Internet generally worked like a big newspaper or TV station. The people who knew what they were doing created the stuff online; the rest of us peons just looked at it.

That’s all changing. Why shouldn’t you create a Web site, blog, or podcast, just like the ones created by the big boys? Or, rather, not like theirs—but better, funnier, more personal? This book show you how to use the new generation of incredibly easy-to-use software designed for just these reasons.

How do I avoid the nasty stuff? The Internet isn’t just an amazing channel for ordinary, law-abiding citizens. It’s also the best thing to happen to scam artists since the invention of innocence.

Spammers fill your email inbox with junk mail, some of it fraudulent. Virus writers, driven by a rotten soul and a perverse desire to get noticed by the world, write software that’s deliberately designed to gum up the works of your PC. Spyware authors disguise their evil programs to trick you into downloading them. Phishing scammers try to make you believe that your bank, eBay, PayPal, or some other important institution needs you to reinput your account information—and direct you to what turns out to be a phony Web site that sends this information right back to the scammer. Here and there, you even hear about pedophiles who hang out in your kids’ chat rooms and try to lure them into personal meetings.

All of this unpleasantness saps the Internet of a lot of its joy. Still, just being aware of the tricks that the baddies might try to play on you is the most important step in avoiding them; at this point, you can still outsmart most of these traps just by not stepping into them.

Chapter 21 is dedicated to what you need to do to stay safe. And throughout the book you’ll find tips and advice on how to keep your guard up. The ground rules are: (a) If it seems to good to be true, it probably is. (b) Don’t open file attachments sent to you by email from people you don’t know. (c) Don’t ever respond to a special offer sent to you by email. (d) Banks, eBay, and similar outfits will never email you to ask for your account information.

The Internet: The Missing Manual is designed to accommodate readers at every technical level. If you’re just getting into this whole Internet thing, great; you’ll find that the introductory material at the beginning of each discussion will help you along from square one.

But even if you’re already online and comfortable with the Net, you’ll find useful tips and tricks, not to mention a world of wisdom in the capsule summaries of the Internet’s most useful Web sites.

The primary discussions are written for advanced-beginner or intermediate computer users. But if you’re a first-timer, miniature sidebar articles called “Up to Speed” provide the introductory information you need to understand the topic at hand. If you’re more advanced, on the other hand, keep your eye out for similar shaded boxes titled “Power Users’ Clinic.” They offer more technical tips, tricks, and shortcuts for the experienced Internet fan.

About → These → Arrows

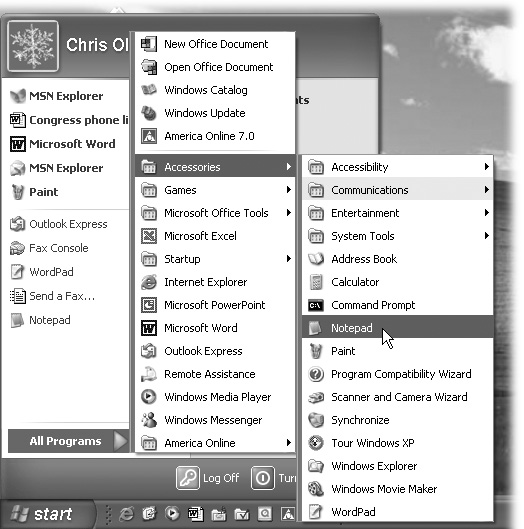

Throughout this book, and throughout the Missing Manual series, you’ll find sentences like this one: “Open the System folder → Libraries → Fonts folder.” That’s shorthand for a much longer instruction that directs you to open three nested folders in sequence, like this: “On your hard drive, you’ll find a folder called System. Open that. Inside the System folder window is a folder called Libraries; double-click it to open it. Inside that folder is yet another one called Fonts. Double-click to open it, too.”

Similarly, this kind of arrow shorthand helps to simplify the business of choosing commands in menus, as shown in Figure I-1.

About MissingManuals.com

To get the most out of this book, visit www.missingmanuals.com. Click the “Missing CD-ROM” link to reveal a neat, organized, chapter-by-chapter list of the shareware and freeware mentioned in this book.

The Web site also offers corrections and updates to the book (to see them, click the book’s title, then click “View/Submit Errata”). In fact, you’re invited and encouraged to submit such corrections and updates yourself. In an effort to keep the book as up-to-date and accurate as possible, each time we print more copies of this book, we’ll make any confirmed corrections you’ve suggested. We’ll also note such changes on the Web site, so that you can mark important corrections into your own copy of the book, if you like.

In the meantime, we’d love to hear your suggestions for new books in the Missing Manual line. There’s a place for that on the Web site, too, as well as a place to sign up for free email notification of new titles in the series.

The Very Basics

To use this book, and indeed to use a computer, you need to know some basics. This book assumes that you’re familiar with a few terms and concepts:

Clicking. This book gives you three kinds of instructions that require you to use the mouse that’s attached to your computer. To click means to point the arrow cursor at something on the screen and then—without moving the cursor at all—press and release the clicker button on the mouse (or your laptop trackpad). If your mouse or trackpad has two buttons, the “clicker button” is the left button.

To double-click, of course, means to click twice in rapid succession, again without moving the cursor at all. And to drag means to move the cursor while holding down the button.

When you’re told to Ctrl+click something, you click while pressing the Ctrl key (on the bottom row of the keyboard). Such related procedures as Shift+clicking and Alt+clicking work the same way—just click while pressing the corresponding key at the bottom of your keyboard.

Shortcut menus. One of the most important features of Windows and Mac OS X isn’t on the screen—it’s under your hand. As noted above, you use the left mouse button to click buttons, highlight text, and drag things around on the screen.

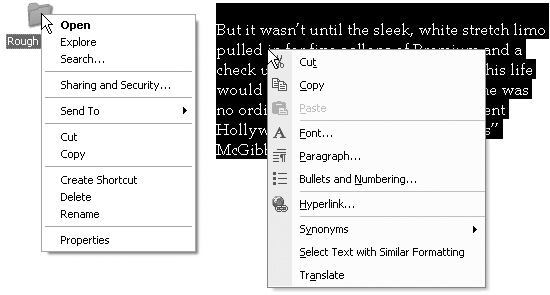

When you click the right button, however, a shortcut menu appears onscreen, like the ones shown in Figure I-2. (On a Macintosh with only one mouse or trackpad button, you “right-click” something by holding down the Control key as you click.)

Figure I-2. Shortcut menus (sometimes called contextual menus) often list commands that aren’t in the menus at the top of the window. Here, for example, are the commands that appear when you right-click a folder (left) and some highlighted text in a word processor (right). Once the shortcut menu has appeared, left-click the command you want.Get into the habit of right-clicking things on the Internet—email messages, Web-page photos, text in an article, and so on. The commands that appear on the shortcut menu will make you much more productive and lead you to discover handy functions you never knew existed.

Menus. The menus are the words at the top of your window or screen: File, Edit, and so on. Click one to make a list of commands appear, as though they’re written on a window shade you’ve just pulled down.

Keyboard shortcuts. If you’re typing along in a burst of creative energy, it’s sometimes disruptive to have to take your hand off the keyboard, grab the mouse, and then use a menu (for example, to use the Bold command). That’s why many experienced computer fans prefer to trigger menu commands by pressing certain combinations on the keyboard. For example, in most word processors, you can press Ctrl+B to produce a boldface word (on the Macintosh, it’s

-B). When you read an instruction like “press Ctrl+B,” start by pressing the Ctrl key, then, while it’s down, type the letter B, and finally release both keys.

-B). When you read an instruction like “press Ctrl+B,” start by pressing the Ctrl key, then, while it’s down, type the letter B, and finally release both keys.Icons. The colorful inch-tall pictures that appear in your various desktop folders are the graphic symbols that represent each program, disk, and document on your computer. If you click an icon one time, it darkens; you’ve just highlighted or selected it, in readiness to manipulate it by using, for example, a menu command.

If you’ve mastered this much information, you have all the technical background you need to enjoy The Internet: The Missing Manual.

Safari® Enabled

When you see a Safari® Enabled icon on the cover of your favorite technology book, that means the book is available online through the O’Reilly Network Safari Bookshelf.

Safari offers a solution that’s better than e-books. It’s a virtual library that lets you easily search thousands of top tech books, cut and paste code samples, download chapters, and find quick answers when you need the most accurate, current information. Try it for free at http://safari.oreilly.com.

Get The Internet: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.