Chapter 1. The myth of epiphany

While waiting in the lobby of Google’s main building, I snuck into the back of a tour group heading inside. These outsiders, a mix of executives and business managers, had the giddy looks of kids in a candy factory—their twinkling eyes captivated by Google’s efforts to make a creative workplace. My clandestine activities unnoticed, we strolled together under the high ceilings and brightly colored open spaces designed to encourage inventiveness. No room or walkway was free of beanbag chairs, ping-pong tables, laptops, and Nerf toys, and we saw an endless clutter of shared games, brain-teasing puzzles, and customized tech gadgetry. The vibe was a happy blend of the MIT Media Lab, the Fortune 500, and an eccentrically architected private library, with young, smart, smiley people lingering just about everywhere. To those innocents on the tour, perhaps scarred survivors of cubicle careers, the sights at Google were mystical—a working wonderland. And their newfound Google awe was the perfect cover for me to tag along, observing their responses to this particular approach to the world of ideas (see Figure 1-1).

The tour, which I took in 2006 after they moved to their Mountain View headquarters, offered fun facts about life at Google, like the free organic lunches in the cafeteria and power outlets for laptops in curious places (stairwells, for example), expenses taken to ensure Googlers are able, at all times, to find their best ideas. While I wondered whether Beethoven or Hemingway, great minds noted for thriving on conflict, could survive in such a nurturing environment without going postal, my attention was drawn to questions from the tourists. A young professional woman, barely containing her embarrassment, asked, “Where is the search engine? Are we going to see it?”, at which only half the group laughed. (There is no singular “engine”—only endless dull bays of server computers running the search-engine software.)

The second question, though spoken in private, struck home. A 30-something man turned to his tour buddy, leaning in close to whisper. I strained to overhear without looking like I was eavesdropping. He pointed to the young programmers in the distance, and behind a cupped hand, he questioned, “I see them talking and typing, but when do they come up with their ideas?” His buddy stood tall and looked around, as if to discover something his friend had missed: a secret passageway, epiphany machines, or perhaps a circle of black-robed geniuses casting creativity spells. Finding nothing, he shrugged. They sighed, the tour moved on, and I escaped to consider my observations.

The question of where ideas come from is on the mind of anyone visiting a research lab, an artist’s workshop, or an inventor’s studio. It’s the secret we hope to see—the magic that happens when new things are born. Even in environments geared for creativity like Google, staffed with the best and brightest, the elusive nature of ideas leaves us restless. We want creativity to be like opening a soda can or taking a bite of a sandwich: mechanical things that are easy to observe. Yet, simultaneously, we hold ideas to be special and imagine that their creation demands something beyond what we see every day. The result is that tours of amazing places, even with full access to creators themselves, never convince us that we’ve seen the real thing. We still believe in our hearts there are top-secret rooms behind motion-sensor security systems or bank-vault doors where ideas are neatly stacked up like bars of gold.

For centuries before Google, MIT, and IDEO—modern hotbeds of innovation—we struggled to explain any kind of creation, from the universe itself to the multitudes of ideas around us. While we can make atomic bombs and dry-clean silk ties, we still don’t have satisfying answers for simple questions like: Where do songs come from? Is there an infinite variety of possible kinds of cheese? How did Shakespeare and Stephen King create so much, while we’re satisfied watching sitcom reruns? Our popular answers have been unconvincing, enabling misleading, fantasy-laden myths to flourish.

One grand myth is the story of Isaac Newton and the discovery of gravity. As it’s often told, Newton was sitting under a tree, an apple fell on his head, and the idea of gravity was born. It’s entertaining more than truthful, turning the mystery of ideas into something innocent, obvious, and comfortable. Instead of hard work, personal risk, and sacrifice, the myth suggests that great ideas come to people who are lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time. The catalyst of the story isn’t even a person: it’s the sad, nameless, suicidal apple.

It’s disputed whether Newton ever observed an apple fall. He certainly was never struck by one, unless there’s secret evidence of fraternity food fights while he was studying in Cambridge. Even if the apple incident took place, the legend discounts Newton’s 20 years of work to explain gravity. Just as Columbus didn’t discover America, Newton did not actually discover gravity—the Egyptian pyramids and Roman coliseums prove that people understood the concept well before Newton. Rather, he used math to explain more precisely than anyone before him how gravity works. While this contribution is certainly important, it’s not the same as discovery.

The best possible truth to take from the apple myth is that Newton was a deeply curious man who spent time observing things in the world. He watched the stars in the sky and studied how light moved through air, all as part of his scientific work to understand the world. It was no accident that he studied gravity. Even if the myth were true and he did see an apple fall, he made so many other observations based on ordinary things that his thinking couldn’t have been solely inspired by fruity accidents in the park.

Newton’s apple myth is a story of epiphany or “a sudden manifestation of the essence or meaning of something,”[2] and in the mythology of innovation, epiphanies serve an important purpose. The word has religious origins, and it initially meant that all insight came by divine power. This isn’t surprising because most early theologians,[3] including Christians, defined God as the sole creative force in the universe. As a rule, people believed that if it’s creative, it’s divine, but if it’s derivative, it’s human. Had you asked the first maker of the wheel[4] for an autograph, he’d likely be offended that you’d want his name instead of his god’s (one wonders what he’d think of Mr. Goodyear and his eponymous tires).[5]

Today, we use epiphany without awareness of its heavy-duty heritage, as in “I had an epiphany for rearranging my closet.” While the religious connotations are forgotten, the implications remain: we’re hinting that we don’t know where the idea came from and won’t take credit for it. Even the language we use to describe ideas—that they come to us or that we have to find them—implies that they exist outside of us, beyond our control. This way of thinking is helpful when we want to assuage our guilt over blank sheets of paper where love letters, business plans, and novels are supposed to be, but it does little to improve our innate creative talents.

The Greeks were so committed to ideas as supernatural forces that they created an entire group of goddesses (not one but nine) to represent creative power; the opening lines of both The Iliad and The Odyssey begin with calls to them.[6] These nine goddesses, or muses, were the recipients of prayers from writers, engineers, and musicians. Even the great minds of the time, like Socrates and Plato, built shrines and visited temples dedicated to their particular muse (or muses, for those who hedged their bets). Right now, under our very secular noses, we honor these beliefs in our language, as the etymology of words like museum (“place of the muses”) and music (“art of the muses”) come from the Greek heritage of ideas as superhuman forces.

When amazing innovations arise and change the world today, the first stories about them mirror the myths from the past. Putting accuracy aside in favor of echoing the epiphany myth, reporters and readers first move to tales of magic moments. Tim Berners-Lee, the man who invented the World Wide Web, explained:

Journalists have always asked me what the crucial idea was or what the singular event was that allowed the Web to exist one day when it hadn’t before. They are frustrated when I tell them there was no Eureka moment. It was not like the legendary apple falling on Newton’s head to demonstrate the concept of gravity…it was a process of accretion (growth by gradual addition).[7]

No matter how many times he relayed the dedicated hours of debate over the Web’s design, and the various proposals and iterations of its development, it’s the myth of magic that journalists and readers desperately want to uncover.

When the founders of the eBay Corporation[8] began, they struggled for attention and publicity from the media. Their true story, that they desired to create a perfect market economy where individuals could freely trade with each other, was too academic to interest reporters. It was only when they invented a quasi-love story—about how the founder created the company so his fiancée could trade PEZ dispensers—that they got the press coverage they wanted. The truer story of market economies wasn’t as palatable as a tale of muse-like inspiration between lovers. The PEZ story was one of the most popular company inception stories told during the late 1990s, and it continues to be told despite confessions from the founders. Myths are often more satisfying to us than the truth, which explains their longevity and resistance to facts: we want to believe that they’re true. This begs the question: is shaping the truth into the form of an epiphany myth a kind of lie, or is it just smart PR?

Even the tale of Newton’s apple owes its mythic status to the journalists of the day. Voltaire and other popular 18th-century writers spread the story in their essays and letters. An eager public, happy to hear the ancient notion of ideas as magic, endorsed and embellished the story (e.g., the apple’s trajectory moved over time, from being observed in the distance to landing at his feet to eventually striking Newton’s head in a telling by Isaac D’Israeli[9] decades later). While it is true that by dramatizing Newton’s work Voltaire helped popularize Newton’s ideas, two centuries later little of Newton’s process is remembered: myths always serve promotion more than education. Anyone wishing to innovate must seek better sources and can easily start by examining the history of any idea.

Ideas never stand alone

The computer keyboard I’m typing on now involves dozens of ideas and inventions. It’s composed of the typewriter, electricity, plastics, written language, operating systems, circuits, USB connectors, and binary data. If you eliminated any of these things from the history of the universe, the keyboard in front of me (as well as the book in front of you) would disappear. The keyboard, like all innovations, is a combination of things that existed before. The combination might be novel, or used in an original way, but the materials and ideas all existed in some form somewhere before the first keyboard was made. Similar games can be played with cell phones (telephones, computers, and radio waves), fluorescent lights (electric power, advanced glass moldings, and some basic chemistry), and GPS navigation (space flight, high-speed networks, atomic clocks). Any seemingly grand idea can be divided into an infinite series of smaller, previously known ideas. An entire television series called Connections (by science historian James Burke) was dedicated to exploring the theme of the surprising relationships between ideas and their interconnectedness throughout history.[10] Similar patterns exist in the work of innovation itself. For most, there is no singular magic moment; instead, there are many smaller insights accumulated over time. The Internet required nearly 40 years of innovations in electronics, networking, and packet-switching software before it even approximated the system Tim Berners-Lee used to create the World Wide Web.[11] The refrigerator, the laser, and the dishwasher were disasters for decades before enough of the cultural and technological barriers were eliminated through various insights, transforming the products into true business innovations. Big thoughts are fun to romanticize, but it’s many small insights coming together that bring big ideas into the world.

However, it’s often not until people try their own hands at innovation or entrepreneurship that they see past the romance and recognize the real challenges. It’s easy to read shallow, mythologized accounts of what Leonardo da Vinci, Thomas Edison, or Jeff Bezos did, and make the mistake of mimicking their behavior in an entirely different set of circumstances (or with comparatively modest intellects). The myths are so strong that it’s a surprise to many to learn that having one big idea isn’t enough to succeed. Instead of wanting to innovate, a process demanding hard work and many ideas, most want to have innovated. The myth of epiphany tempts us to believe that the magic moment is the grand catalyst; however, all evidence points to its more supportive role.

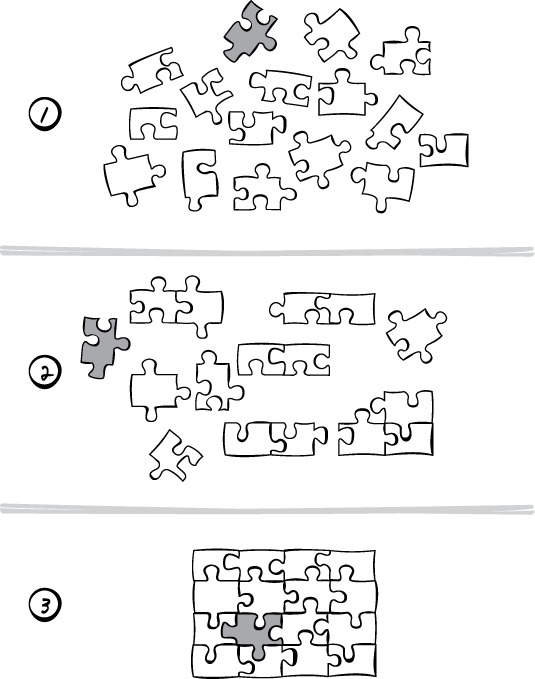

One way to think about epiphany is to imagine working on a jigsaw puzzle. When you put the last piece into place, is there anything special about that last piece or what you were wearing when you put it in? The only reason that last piece is significant is because of the other pieces you’d already put into place. If you jumbled up the pieces a second time, any one of them could turn out to be the last, magical piece. Epiphany works the same way: it’s not the apple or the magic moment that matters much, it’s the work before and after (see Figure 1-2).

The magic feeling at the moment of insight, when the last piece falls into place, comes for two reasons. The first reason is that it’s the reward for many hours (or years) of investment coming together. In comparison to the simple action of fitting the puzzle piece into place, we feel the larger collective payoff of hundreds of pieces’ worth of work. The second reason is that innovative work isn’t as predictable as jigsaw puzzles, so there’s no way to know when the moment of insight will come. It’s a surprise. Like hiking up a strange mountain through cold, heavy fog, you never know how much farther you have to go to reach the top. When suddenly the air clears and you’re at the summit, it’s overwhelming. You hoped it was coming, but you couldn’t be certain when or if it would happen, and the emotional payoff is hard to match (explaining both why people climb mountains and invent new things).

Gordon Gould, the primary inventor of the laser, had this to say about his own epiphany:

In the middle of one Saturday night…the whole thing…suddenly popped into my head and I saw how to build the laser…but that flash of insight required the 20 years of work I had done in physics and optics to put all of the bricks of that invention in there.

Any major innovation or insight can be seen in this way. It’s simply the final piece of a complex puzzle falling into place. But unlike a puzzle, the universe of ideas can be combined in an infinite number of ways, so part of the challenge of innovation is coming up with the problem to solve, not just its solution. The pieces used to innovate one day can be reused and reapplied to innovate again, only to solve a different problem.

The other great legend of innovation and epiphany is the tale of Archimedes’ Eureka. As the story goes, the great inventor Archimedes was asked by his king to detect whether a gift was made of false gold. One day, Archimedes took a bath, and on observing the displacement of water as he stepped in, he recognized a new way to look at the problem: by knowing an object’s volume and weight, he could compute its density. He ran naked into the streets yelling “Eureka!”—I have found it—and perhaps scandalizing confused onlookers into curious thoughts about what exactly he had been looking for.

The part of the story that’s overlooked, like Newton’s apple tale, is that Archimedes spent significant time trying and failing to find solutions to the problem before he took the bath. The history is sketchy at best, but I suspect he took the bath as stress relief from the various pressures of innovation.[12] Unlike Google employees, or the staff at the MIT Media Lab, he didn’t have friends with Nerf weapons or sand volleyball courts where he could blow off steam. So, as is common in myths of epiphany, we are told where he was when the last piece fell into place, but nothing about how the other pieces got there.

In Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s book, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention,[13] he studied the thought processes of nearly 100 creative people, from artists to scientists, including notables like Robertson Davies, Stephen Jay Gould, Don Norman, Linus Pauling, Jonas Salk, Ravi Shankar, and Edward O. Wilson. Instead of doing clinical research with probes and brain scans, he focused instead on the innovators’ individual insights. He wanted to understand their perceptions of innovation, unfiltered by the often stifling and occasionally self-defeating rigors of hard science.

One goal was to understand epiphany and how it happens; through his research, he observed a common pattern. Epiphany had three parts, roughly described as early, insight, and after.[14] During the early period, hours or days are spent understanding the problem and immersing oneself in the domain. An innovator might ask questions like “What else in the world is like this?” and “Who has solved a problem similar to mine?”, learning everything he can and exploring the world of related ideas. And then there is a period of incubation in which the knowledge is digested, leading to experiments and rough attempts at solutions. Sometimes there are long pauses during incubation when progress stalls and confidence wanes, an experience the Greeks would have called “losing the muse.”

The big insights, if they happen, occur in the depths of incubation; it’s possible these pauses are minds catching up with everything they’ve observed. Csikszentmihalyi explains that deep quiet periods, time spent doing unrelated things, often helps new ideas surface. He writes, “Cognitive accounts of what happens during incubation assume…that some kind of information processing keeps going on even when we are not aware of it, even while we are asleep.” Our subconscious minds play large roles in creative thinking: they may be the sources for the unexplained insights we romanticize. When a promising idea surfaces out of the subconscious and rises into our active minds, it can feel like it came from somewhere else because we weren’t aware of our subconscious thoughts while we were mowing the lawn.

The best lesson from the myths of Newton and Archimedes is to work passionately but to take breaks. Sitting under trees and relaxing in baths lets the mind wander and frees the subconscious to do work on our behalf.[15] Freeman Dyson, a world-class physicist and author, agrees: “I think it’s very important to be idle…people who keep themselves busy all the time are generally not creative. So I am not ashamed of being idle.” This isn’t to justify surfing instead of studying: it’s only when activities are done as breaks that the change of activity pays off. Some workaholic innovators tweak this by working on multiple projects at the same time, effectively using work on one project as a break from the other. Edison, Darwin, da Vinci, Michelangelo, and van Gogh all regularly switched between different projects, occasionally in different fields, possibly accelerating an exchange of ideas and seeding their minds for new insights.

One of the truths of both Newton’s apple tale and Archimedes’ bathtub story is that triggers for breakthroughs can come from ordinary places. There is research indicating that creative people more easily make connections between unrelated ideas.[16] Richard Feynman curiously observed students spinning plates in the Cornell University cafeteria and eventually related the mathematics of this behavior to an unsolved problem in quantum physics, earning him the Nobel Prize. Picasso found a trashed bicycle and rearranged its seat and handlebars, converting it into a masterpiece sculpture of a bull. The idea of observation as the key to insight, rather than IQ scores or intellectual prowess, is best captured by something da Vinci—whose famous technological inventions were inspired by observing nature—wrote hundreds of years ago:

Stand still and watch the patterns, which by pure chance have been generated: Stains on the wall, or the ashes in a fireplace, or the clouds in the sky, or the gravel on the beach or other things. If you look at them carefully you might discover miraculous inventions.

In psychology books, the talent for taking two unrelated concepts and finding connections between them is called associative ability. In his book Creativity in Science: Change, Logic, Genius, and Zeitgeist, Dean Simonton points out that “persons with low associative barriers may think to connect ideas or concepts that have very little basis in past experience or that cannot easily be traced logically.”[17] Read that last sentence again: it’s indistinguishable from various definitions of insanity. The tightrope between being strange and being creative is too narrow to walk without occasionally landing on either side, explaining why so many great minds are lampooned as eccentrics. Their willingness to try seemingly illogical ideas or to make connections others struggle to see invariably leads to judgment (and perhaps giving some truth to stereotypes of mad scientists and unpredictable artists). Developing new ideas requires questions and approaches that most people won’t understand initially, which leaves many true innovators at risk of becoming lonely, misunderstood characters.

Beyond epiphany

If we had a list of the most amazing breakthrough insights that would change the world in the next decade, hard work would follow them all. No grand innovation in history has escaped the long hours required to take an insight and work it into a form useful to the world. It’s one thing to imagine world peace or the Internet, something Vannevar Bush did in 1945 in a paper titled “As We May Think,”[18] but it’s another to break down the idea into parts that can be built, or even attempted.

Csikszentmihalyi describes this part of innovation, the elaboration of an idea into function, as “the one that takes up the most time and involves the hardest work.” Scientists need to not only make discoveries, but to provide enough research to prove to others that the discoveries are valid. Newton was far from the first to consider a system of gravity, but he was the only one to complete the years of work to produce an accurate one in his day. Star Trek, a television program in the ’60s, had the idea for cell phones, but it took decades for technology to be developed and refined to the point where such a thing could be practical (and, of course, many of Star Trek’s sci-fi ideas have yet to be realized). Not to mention the services and businesses that are needed to make the devices affordable to consumers around the world. The big ideas are a small part of the process of true innovation.

The most useful way to think of epiphany is as an occasional bonus of working on tough problems. Most innovations come without epiphanies, and when a powerful moment does happen, little knowledge is granted for how to find the next one. Even in the myths, Newton had one apple and Archimedes had one Eureka. To focus on the magic moments is to miss the point. The goal isn’t the magic moment: it’s the end result of a useful innovation. Ted Hoff, the inventor of the first microprocessor (Intel’s 4004), explained, “If you’re always waiting for that wonderful breakthrough, it’s probably never going to happen. Instead, what you have to do is keep working on things. If you find something that looks good, follow through with it.”[19]

Nearly every major innovation of the 20th century took place without claims of epiphany. The World Wide Web, the web browser, the computer mouse, and the search engine—four pivotal developments in the history of business and technology—all involved long sequences of innovation, experimentation, and discovery. They demanded contributions from dozens of different individuals and organizations, and took years (if not decades) to reach fruition. The makers of Mosaic and Netscape, the first popular web browsers, didn’t invent them from nothing. There had been various forms of hypertext browsers for decades, and they applied some of those ideas to the new context of the Internet. The founders of Google did not invent the search engine—they were years late for that honor. As the founders of Amazon.com, the most well-known survivor of the late-’90s Internet boom, explain, “There wasn’t this sense of ‘My God. We’ve invented this incredible thing that nobody else has seen before, and it’ll just take over.’”[20] Instead they, like most innovators, recognized a set of opportunities—scientific, technological, or entrepreneurial—and set about capitalizing on them.

Peter Drucker, in Innovation and Entrepreneurship,[21] offers advice for anyone in any pursuit awaiting the muse:

Successful entrepreneurs do not wait until “the Muse kisses them” and gives them a “bright idea”: they go to work. Altogether they do not look for the “biggie,” the innovation that will “revolutionize the industry,” create a “billion-dollar business” or “make one rich over-night.” Those entrepreneurs who start out with the idea that they’ll make it big—and in a hurry—can be guaranteed failure. They are almost bound to do the wrong things. An innovation that looks very big may turn out to be nothing but technical virtuosity; and innovation with modest intellectual pretensions, a McDonald’s, for instance, may turn into gigantic, highly profitable businesses.

The same can be said for any successful scientist, technologist, or innovator. What matters is the ability to see a problem clearly, combined with the talent to solve it. Both of those tasks are generally defined, however unglamorously, as work. Epiphany, for all its graces, is largely irrelevant because it can’t be controlled. Even if there existed an epiphany genie, granting big ideas to worthy innovators, the innovators would still have piles of rather ordinary work to do to actualize those ideas. It is an achievement to find a great idea, but it is an even greater achievement to successfully use it to improve the world.

[2] This approximates the third entry in Merriam-Webster’s online listing. The first two are religious in nature: http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/epiphany.

[3] Robert S. Albert and Mark A. Runco, “A History of Research on Creativity,” in Handbook of Creativity, ed. Robert J. Sternberg (Cambridge University Press, 1998), 16–20.

[4] The wheel’s prehistoric origins are a misnomer. The first wheels used for any practical purpose date back to around 3500 BCE. Start with http://www.ideafinder.com/history/inventions/wheel.htm.

[5] The rubber tire was once a big innovation, and the history of Goodyear is a surprisingly good read: http://www.goodyear.com/corporate/history/history_overview.html.

[6] Homer, The Iliad (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition, 1998), and The Odyssey (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition, 1999).

[7] Tim Berners-Lee, Weaving the Web (HarperCollins, 1999).

[8] Adam Cohen, The Perfect Store: Inside eBay (Back Bay Books, 2003).

[9] Isaac D’Israeli, Curiosities of Literature: With a View of the Life and Writings of the Author (Widdleton, 1872).

[11] See the Internet Timeline: http://www.pbs.org/opb/nerds2.0.1/timeline/.

[12] The most well-known version of the Eureka story comes in the form of a legend in Vitruvius’ Ten Books of Architecture (Dover, 1960), 253–255. This book is the first pattern language of design in Western history, documenting the Roman architecture techniques of Vitruvius’ time.

[13] Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention (HarperPerennial, 1997).

[14] Csikszentmihalyi describes epiphany in five phases, but I’ve simplified it to three for the purposes of this chapter.

[15] There is neuroscience research that supports the importance of daydreaming in creativity; see http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2008/08/31/daydream_achiever/.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Dean Keith Simonton, Creativity in Science: Chance, Logic, Genius, and Zeitgeist (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

[18] Bush’s paper is a recommended read. It goes beyond hyperbole and breaks down a vision into smaller, practical problems (a hint for today’s visionaries): http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/194507/bush.

[19] Kenneth A. Brown, Inventors at Work: Interviews with 16 Notable American Inventors (Microsoft Press, 1988).

[20] Paul Barton-Davis, quoted in Robert Spector, Amazon.com: Get Big Fast (HarperBusiness, 2000), 48.

[21] Peter Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Collins, 1993).

Get The Myths of Innovation now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.