In the old days, you pulled the film out of your camera and dunked it in toxic chemicals, or you hired someone else to do that for you. With a digital camera, of course, you don’t need chemistry or lightproof rooms. Instead, after your shoot, you’ll transfer your images to your computer where you can edit and correct them. You can perform this transfer in many ways, and lots of software exists that you can use for editing. In this chapter, you’ll take a look at your transfer options and explore Nikon’s bundled software. Before getting started, let’s consider your camera’s media card.

Film is an amazing invention because it’s a single material that can both capture an image and store it. With a digital camera, the image sensor does the capture, but it doesn’t have any capability to store an image. For that, a digital camera employs a memory card of some kind. As you’ve already learned, the D90 uses Secure Digital cards (or SDHC cards, a faster, higher-capacity version of SD).

Flash memory cards are similar to the RAM that’s in your computer but with one important difference: They don’t require power to remember what’s stored on them. So, after you turn the camera off, the images remain on the card, even if you remove it. Consequently, it’s perfectly safe to take out a full card and replace it with another.

Your camera treats the card just the way your computer treats your hard drive. The camera creates folders on the card and stores files in those folders, each with a different name.

Because cards are so small and because they can pack huge capacities, it’s possible to shoot a tremendous number of images with just one or two cards. In fact, because the D90’s battery is good for “only” about 500 shots, if you’re carrying a couple of high-capacity cards, you’ll probably run out of battery power before you run out of storage.

With the range of capacities available, you can carry storage in several ways. You can get a few high-capacity cards or more lower-capacity cards. The advantage of a high-capacity card is that your shooting won’t be interrupted with a card change. The risk, though, is that if something happens to the card, all your images will be lost.

Though it’s rare, a Secure Digital card can be corrupted. Sometimes static electricity can do it; sometimes a glitch in your computer or in your camera can mess up a card. Although the card probably won’t be permanently damaged, its contents can be rendered unusable. So, you might want to consider using more, smaller cards so that if one goes bad, you won’t lose as many images.

For maximum flexibility, you might want a combination: a big card that you can use when you’re shooting events such as a performance or sporting event and don’t want to miss shots because of a card change, and smaller cards that you use for everyday shooting. You may have to change them more often, but your images will be safer in the event of a card failure.

When you’re in the field, you’ll need to keep track of which cards you’ve used and which are available for shooting. If you’re shooting on the go, you don’t want to have to worry about whether the card you’re about to use already has images on it. You can ease your card management hassles when shooting in a few ways.

First, after you transfer your images to your computer, erase the card. We’ll look at how to do this later in this chapter. After you’ve transferred images, if you just throw the cards back in your camera bag with the idea of erasing them when you’re ready to use them, you can easily end up confused as to whether the card has already been transferred. If you become uncertain, you might be less willing to use the card, and then you can end up short on storage. Also, if you erase beforehand, when you put the card in the camera, it’s ready to use, right away.

Second, if you have a camera bag with a lot of pouches and compartments, consider using one pouch for unused cards and another for used cards. This makes it simple to keep track of which media is ready for use.

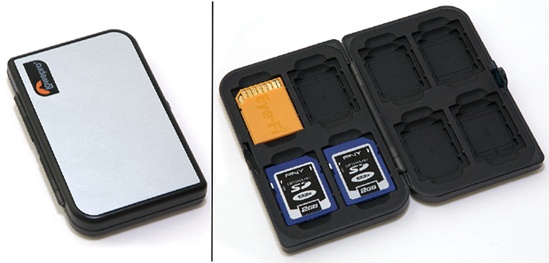

I carry my cards in a small holder. When I fill up a card, I place it back in the holder, facedown. That way, I can easily see how many cards are remaining and be certain that I’m grabbing a card that’s ready for use. I use a holder made by Lowepro (www.lowepro.com).

Figure 4-1. A card holder can make it much easier to manage your cards while shooting. Upside-down cards are full; face-up cards are ready for use.

At some point, though, your cards will be full, and you’ll be ready to transfer your images to your computer.

Every image you shoot is stored on your camera’s media card as an individual file. The file is a document just like you might create on your computer. Before you can do any editing of your images using your computer, you have to copy those image documents from your camera’s media card onto your computer’s hard drive.

You can transfer images from your camera in two ways. You can plug the camera directly into your computer, or you can remove its media card and place it in a media reader that is connected to your computer.

The advantage of a card reader is that it doesn’t consume any of your camera’s battery power. Also, most card readers support lots of different formats, so if you have multiple cameras (say, the D90 and a small point-and-shoot) and they use different formats, then you need to carry only one card reader and a cable.

Depending on the type you get, a card reader might provide faster transfer than the D90. You should be able to find card readers that connect to your computer’s USB 2 or FireWire port.

If you have a laptop with a PC Card slot or a CardBus 34 slot, then you can get card readers that will fit in those slots. These are typically the fastest readers of all, but they rarely support multiple formats.

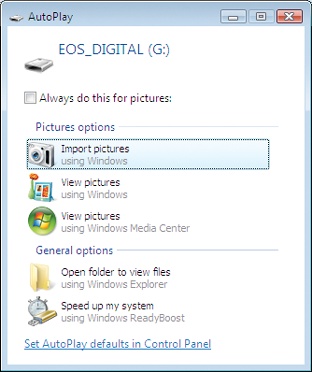

Figure 4-2. On the left is a CardBus card reader that can plug directly into a CardBus slot on a laptop. On the right is a card reader that plugs into a USB 2 slot. Note the huge number of card formats that it supports.

REMINDER: Don’t Forget SDHC

If you’re shopping for an SD card reader, be sure to get one that also supports SDHC. Since the D90 supports SDHC, you might end up buying SDHC cards at some point, so you might as well have a reader that can handle them as well as regular SD.

The D90 ships with a USB cable that you can plug directly into your computer. This allows you to use your camera as a card reader, saving you the hassle of keeping track of an extra piece of gear. However, if you have an especially speedy reader, transferring from the camera might be slower, and as mentioned before, camera transfer will use up battery power.

QUESTION: What If the Reader Can’t Read My Card?

Sometimes you might find that a card that has always worked fine in your card reader suddenly won’t read. If this happens, put the card back in the camera, and see whether you can view images on the camera’s screen. If you can, then you know that the camera can read the card just fine. Plug the camera into your computer, and try transferring the images that way. It will usually work. When you’re done, perform a low-level format (explained in Chapter 3). This will usually get the card working with your card reader again.

What happens on your computer when you plug in a card reader or camera will vary depending on the operating system that you’re using. In the next two sections I’ll go over the separate options available for Windows and Mac users.

Even if you plan on using some other software for editing, it’s worth taking a look at the bundled Nikon software. Although you may not ultimately use it in your workflow, it’s worth knowing what it’s capable of, and I’ll be using it for some of the examples in this book, so it will be good for you to be able to follow along.

The Nikon Software Suite Disk that’s included in the D90 box is a hybrid disc that works with the Mac or Windows. To install the software, insert the CD in your computer, and run the installer. The disc puts a number of applications on your computer, with some slight variations between the Mac and Windows.

I’ll cover how you might use this software in the following sections.

If you’re using Microsoft Windows XP or Vista, you’ll find that Windows will take care of a lot of image transfer hassles for you. If want to customize your transfer experience, you can easily do that to build the type of workflow that you like.

When you plug a card reader or camera into Vista or XP for the first time, Windows might make some kind of mention of installing a new driver.

Figure 4-3. When plugging in a card reader for the first time, Windows might tell you it’s installing a new driver.

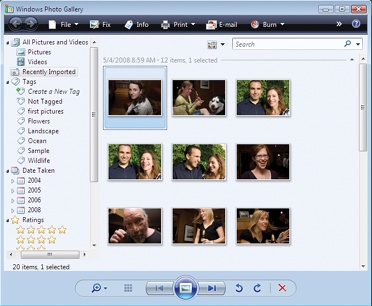

Follow any necessary onscreen instructions to get the camera or card reader working. Once the card reader or camera is configured, Windows will show you a simple window that lets you specify what you want done with the images on the card.

Figure 4-4. Windows lets you choose what you want to have happen when you plug in a card reader or camera.

- Import Pictures

lets you copy the images on your card to a specific directory on your hard drive. By default, Import Pictures copies images into your Pictures directory. When you first choose Import Pictures, Windows will show you a simple dialog box, which gives you an Import button and an option to add a text tag to your images. Tags make it easier to sort and filter your images later.

If you click the Options button, you’ll see a more advanced dialog box that offers additional options:

Figure 4-5. Using these controls, you can specify which directory you want the pictures imported into, and you can define naming conventions.

Once your images have been imported, Windows will show them to you in Windows Photo Gallery.

- View Pictures Using Windows

will open Windows Photo Gallery, which lets you thumb through large views of your images. Using the menu items at the top, you can choose to import the images, print them, or even perform simple image edits.

- View Pictures Using Windows Media Center

lets you view the images on the card using Windows Media Center, which offers a full-screen interface, with easy navigation to other images on your system.

Finally, notice the Always Do This for Pictures check box at the top of the dialog box. This allows you to specify default behavior for a card insertion.

Which option is right for you depends largely on the rest of your workflow. If you think you can manage your entire postproduction workflow in Windows Photo Gallery or Windows Media Center, then these are all good options. If you plan on using some different image-editing software, then you can still use the Import Pictures command to copy your images to a directory.

Alternatively, you might want to use the Open Folder to View Files Using Windows Explorer option, which gives you the chance to manually copy the files using Windows Explorer. Depending on what software you have installed, the menu might contain other options, such as Adobe Bridge. Once you’ve copied your images, you can work with them using your choice of programs.

I’ll outline some other options in the following sections.

Changing Your Media Card Preferences

If you select the Always Do This for Pictures check box, configure an option, and then decide later that you’d like something else to happen when you insert a card, you can change Windows’ behavior using Control Panel.

From the Start menu, choose Control Panel, and then select Hardware and Sound. On the following screen, find the AutoPlay section, and click Change Default Settings for Media or Devices. Here, you can edit the Pictures category to select a different option, or you can choose Ask Me Every Time to get Windows to present you with a dialog box of choices.

Using Adobe Photoshop Elements for Windows

If you’ve installed Adobe Photoshop Elements, then when you attach a media card reader or camera to your computer, the Elements Photo Downloader will automatically launch.

The Photo Downloader lets you choose a location to store your files and can create subfolders within that location based on the date and time stamp on each image. Photo Downloader can also rename your images from the nonsensical camera names to something more meaningful.

If you click the Advanced Dialog button at the bottom of the screen, you’ll get an interface that lets you select which images you want to download as well as use some more advanced options such as the ability to add metadata to each image. Metadata consists of notes and tags—such as your name, copyright info, or organizational keywords—that get added to the image.

Photoshop Elements is a great image editor with all the features you’ll need for almost any image-editing task, so if you plan on using Elements for your image editing, you might want to explore Photo Downloader for your image transfers, simply because of its Elements integration.

The full version of Photoshop provides all the features of Photoshop Elements, along with some more high-end features that you may or may not need. If you think you might need the ability to prepare images for offset printing or if you routinely work with high-end 3D imaging, scientific, or video/film production software, then Photoshop will be a welcome addition to your toolbox. Otherwise, it’s probably overkill for your photo-editing needs, and the money you’d spend on the full-blown version of Photoshop would easily pay for Elements and a new lens for your D90.

If you do install Photoshop CS3 or CS4 (or Photoshop Elements on the Macintosh), you’ll also get Adobe Bridge, an excellent image browser that has its own image transfer features.

Whether you use a card reader or plug directly into your camera, transferring images to your Mac is very simple, and you have a number of options for determining what happens when you attach the camera or card reader.

Depending on what kind of Mac you have and when you bought it, you might have a copy of iPhoto, Apple’s image-organizing and editing program. iPhoto is very good and can handle the transfer of images from your media card, as well as help you with the rest of your photographic workflow, from organizing to editing to output.

iPhoto is part of Apple’s iLife suite, and it comes bundled on many new Macs. If your Mac doesn’t have it, you can buy the latest version from any vendor that sells Apple products.

Whether or not you have iPhoto, every Mac ships with a copy of Image Capture, a small utility that helps manage the transfer of images into your computer. Image Capture has no editing or organization features—its sole purpose is to get images copied onto your hard drive. Once they’re there, you can decide what to do with them.

If you installed the software from the Nikon Software Suite Disk, then you’ll have some additional software on your Mac, which I’ll cover later. You might also have other editing software that you want to use, such as Adobe Photoshop or Photoshop Elements. These programs can also manage the transfer of images to your computer.

You can tell your Mac what you want to have happen when you plug in a camera or media card reader. This makes it simple to choose what software you want to use to transfer your images.

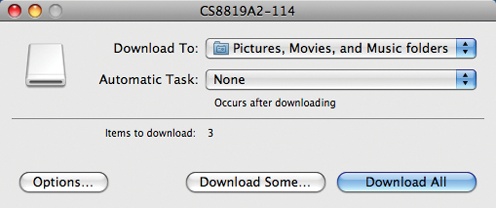

In your Applications folder there should be a program called Image Capture. By default, Image Capture will open automatically any time you plug in a camera or card reader and will present a window for managing the transfer of images.

Figure 4-9. Image Capture is included on all Macs and provides a simple way to manage the transfer of images from a camera or media card reader.

Image Capture lets you choose where you want your images downloaded and what to do after the images have been copied, and if you click the Download Some button, you can even select specific images to copy.

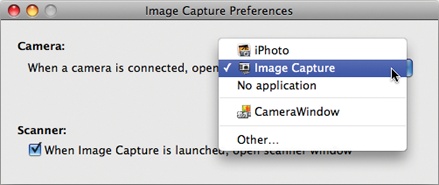

Image Capture also lets you specify what you want your Mac to do when you plug in a card reader or camera. If you go to the Capture menu and choose Preferences, you’ll see a pop-up menu that lets you select which application you want to have launched whenever a camera or media card reader is plugged in to your Mac. When you installed the Nikon software, you were probably given the option of having Nikon Transfer open anytime a camera or card reader is plugged in. We’ll look at Nikon Transfer later in this section.

Figure 4-10. Using the preferences in Image Capture, you can control what should happen when a camera or media card reader is connected to your Mac.

By default, the menu will list iPhoto (if you have it), Image Capture, and possibly other applications, including Nikon Transfer, if you have them installed. If you have a program installed that you’d like to use but you don’t see it listed, choose Other. Image Capture will present you with a dialog box that allows you to pick the program you’d like to use.

Finally, if you’d like complete manual control, you can choose No Application.

You can change this menu at any time if you later want to change your image transfer preference. We’ll go over a few image transfer options in the following sections.

If you installed the Nikon Software Suite Disk, then you’ll also have a copy of Nikon Transfer, Nikon’s software for managing the copying of images from media cards to your computer.

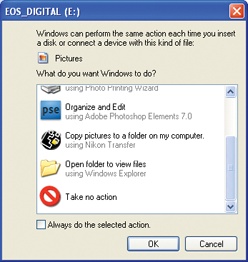

If you have Nikon Transfer installed on Windows, then Windows will provide an additional option when you insert a media card. Copy Pictures to a Folder on My Computer Using Nikon Transfer will let you transfer images using Nikon Transfer.

Figure 4-11. If you’ve installed the Nikon Software Suite Disk, then copying images using Nikon Transfer will be an additional import option. If you decide you like Nikon Transfer, select Always Do the Selected Action to make Nikon Transfer your default choice.

If you’re a Mac user, then you can configure the OS to automatically launch Nikon Transfer when you insert a media card. See the previous section for details.

Nikon Transfer provides a single dialog box with five different tabs for configuring the specifics of your transfer operation.

When the program launches, the Source tab should automatically configure itself to point to the card that you inserted. If it doesn’t, open the Search For menu, and you should see a listing for the card you inserted.

By default, Nikon Transfer will copy all the images on your card. If you prefer to copy only a selection of images, then open the Thumbnails section of the Source tab (if it isn’t open already), and select the images you’d like to transfer.

Figure 4-12. To transfer selected images, in the Source tab, select the box beneath the thumbnail of each image you want to copy.

The buttons at the top of the Thumbnails section allow you to select and deselect all the images or to select images that you marked or protected in the camera. You can even delete selected images by clicking the trash icon. Hold the mouse over each button to see a tool tip that describes its function.

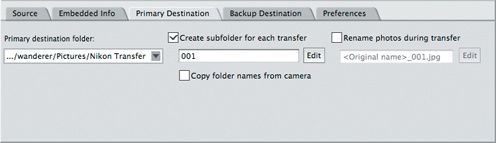

Once you’ve selected the images you want to copy, you need to tell Nikon Transfer where to put the images. Choose the Primary Destination tab to select a folder to copy the images into.

Open the Primary Destination Folder pop-up menu to select a destination. If you would like to create a subfolder within that folder, click the Create Subfolder for Each Transfer box, and enter a folder name.

If you’d like, you can have Nikon Transfer automatically rename your images when it copies them. Check the Rename Photos During Transfer box, and then click the Edit button beneath it to define a naming convention.

You can also have Nikon Transfer automatically make a second copy of your images to a second, backup location. Click the Backup Destination tab, and you’ll find controls for selecting an additional folder. Nikon Transfer will copy the contents of your card to both locations.

On the Preferences tab, you’ll find a number of useful, self-explanatory settings that you can configure.

As you’ve seen, when you take a picture with the D90, it automatically embeds all of your exposure settings in the metadata of the image. Metadata is simply extra data that’s stored alongside the image data in the file that the camera creates.

You can add metadata to your image file, such as a description, title, copyright info, and more. You can add this info at any time, using any number of different tools. Nikon Transfer also lets you add metadata when you import.

Metadata is often image-specific—for example, you might include keywords that describe the image content. But there are some metadata tags that will apply to all of your images, such as your name and copyright information. If all of the images on the card were shot in the same location, then you might want to fill in some of that data before you transfer.

To have Nikon Transfer automatically embed metadata info, follow these steps:

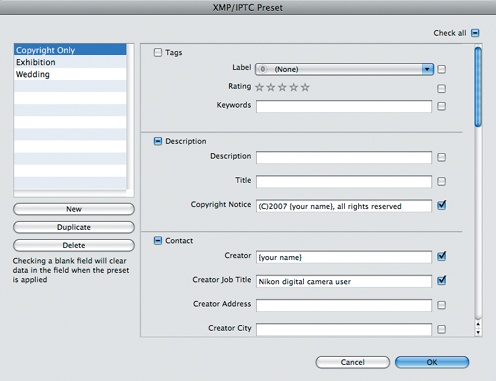

Click the Embedded Info tab. There are several different types of metadata. Your camera embeds EXIF metadata in your image when you shoot—this is the exposure data. XMP and IPTC metadata are additional metadata standards. Using Nikon Transfer, you can define templates containing specific metadata. This allows you to keep a library of commonly used sets of metadata.

Click the Edit button to open the metadata template editor.

On the left side of the window are three presets. Click the New button to create a new preset, and give it any name you like.

Fill in any fields that you like. For example, if you want your copyright information added to all the images, fill in the Copyright Notice field. If you want your name added, then fill in the Creator field. When you’re finished, click OK. Your preset will now appear in the XMP/IPTC Preset pop-up menu on the Embedded Info tab.

If you want complete manual control of your image transfers, configure your computer to do nothing when a camera or card reader is plugged in. This will simply mount the camera or card reader on your desktop, just as if it were a hard drive, leaving you free to copy files as you please.

The advantage of taking a manual approach is that you can completely control where files are placed and create a folder structure on your drive that makes the most sense to you.

The downside to importing using this approach is that, depending on which version of your operating system you’re using, you won’t necessarily be able to see thumbnail previews of your images before you transfer, which means you won’t be able to pick and choose which images to copy. Obviously, you can always sort through them later.

To transfer images manually, simply plug in the camera or card reader. When the camera or card reader icon appears on your desktop, open it. You should see a folder inside called DCIM. There might be some other folders, but DCIM is the only one you need to worry about. It is the standard location that camera vendors have agreed upon for storing images.

Inside the DCIM folder you will find additional folders, usually named with some combination of numbers and “D90” (i.e., “100NCD90”). Depending on how many images you’ve shot, there may be more. Open each folder, and copy its contents to your desired location.

While reviewing images in your camera, you can specify which images you want to transfer to your computer. Of course, you could also just delete the images that you don’t want, which would free up more storage on your card. However, if you’ve shot a bunch of images and need to quickly process and deliver just a few, then marking only those images for transfer will let you quickly get those images to your computer for processing. You can transfer the rest later.

Of course, you can also select images for transfer using your transfer software, but marking images in the camera can be convenient, both because it’s something you can do in the field, when you have spare time, and because you can mark a “keeper” image as soon as you shoot it.

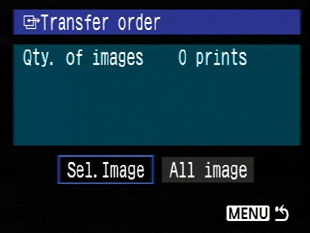

To mark an image for transfer, view the image on the D90’s screen; then hit the Menu button. Choose Transfer Order from the Playback menu. On the resulting menu, choose Sel. Image.

Figure 4-15. Using the Transfer Order page, you can control what images will be transferred to your computer.

ImageBrowser and ZoomBrowser both let you choose to download only images that have been marked in the camera, providing you with a one-button method for getting your order into your computer.

QUESTION: What If I’m Using Photo Management Software?

If you’re using Apple’s iPhoto or Aperture, or Adobe Lightroom (on either a Windows or Mac machine), then those programs can take care of image transfer for you. As with any other application, you’ll need to specify that you want those applications to take over image downloading. Consult the documentation for your program for more information, and be aware that these applications all copy your images into their own library systems, so you don’t need to worry about where the images should be stored. Each program will take care of putting the files in a location that’s right for them.

No matter which method you use to transfer images to your computer, if you’re managing your image organization yourself (as opposed to having a program such as iPhoto, Aperture, or Lightroom do it for you), then you will want to think about how to organize your files.

You’ll be best served in your organizational chores by making good use of folders. How to organize these folders is entirely a matter of personal preference; just find a scheme that makes sense to you. You can create folders by subject—“Arizona vacation,” “Winter holidays,” “Family reunion”—or by date. You’ll probably find that some combination of both works best, especially if you find yourself shooting a lot of similar events.

As you accumulate more vacation folders, you can group these into other folders. With well-named folders, you can easily rearrange your taxonomy later, creating new branches of your naming “tree” and then rearranging photos as needed.

What you probably won’t need to do is rename files. Yes, the images that come out of your camera have pretty meaningless names, but with a browser program such as the one that came with your camera, or programs such as Adobe Bridge or Camera Bits Photo Mechanic, you can search and sort your images by viewing thumbnails, rather than by digging through lists of arcane filenames.

If you do feel compelled to rename your images, renaming by hand is probably not the way to go, unless you’re talking about only a handful of images. Programs like Bridge, Photo Mechanic, and most image browsers provide tools for automatically renaming batches of files. If you think you need to have your individual image files named, then consider using such a utility.

Once you’ve transferred your images, you’ll be ready to start the rest of your postproduction workflow—correcting, editing, adjusting, and outputting your images. With these first four chapters, you should know how to shoot in Auto mode and transfer your results to your computer. This means you can continue to practice while we cover some new topics.

Although modern image-editing software can do some amazing things, how much editing you can perform is limited by the quality of your original shot. So, I’m going to now delve more deeply into some photographic theory so that you can learn to use the more advanced features on the D90. These features will allow you to shoot images that can withstand a much greater level of editing and adjustment.

Get The Nikon D90 Companion now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.