Formal training isn’t really required to become a game designer. Most of the game designers working professionally today are self-taught. That is changing rapidly as university programs for game designers crop up all around the country and the world.*

I went to school to be a writer, mostly. I believe really passionately in the importance of writing and the incredible power of fiction. We learn through stories; we become who we are through stories.

My thinking about what fun is led me to similar conclusions about games. I can’t deny, however, that stories and games teach really different things, in very different ways. Game systems (as opposed to the visuals and presentation of a given game) don’t usually have a moral. They don’t usually have a theme in the sense that a novel has a theme.

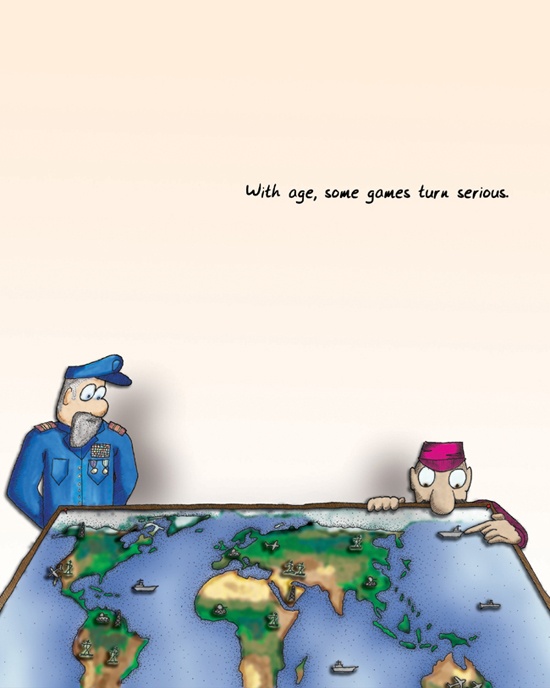

The population that uses games as learning tools the most effectively is the young. Certainly folks in every generation keep playing games into old age (pinochle,* anyone?), but as we get older we view those people more as the exception, though this is changing as digital gaming continues to rise in popularity. Games are viewed as frivolity. In the Bible in 1 Corinthians, we are told, “When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child; when I became a man, I gave up childish ways.”* But children speak honestly—sometimes too much so. Their reasoning is far from impaired—it is simply inexperienced. We often assume that games are childish ways, but is that really so?

We don’t actually put away the notion of “having fun,” as far as I can tell. We migrate it into other contexts. Many claim that work is fun, for example (me included). Just getting together with friends can be enough to give us the little burst of endorphins we crave.

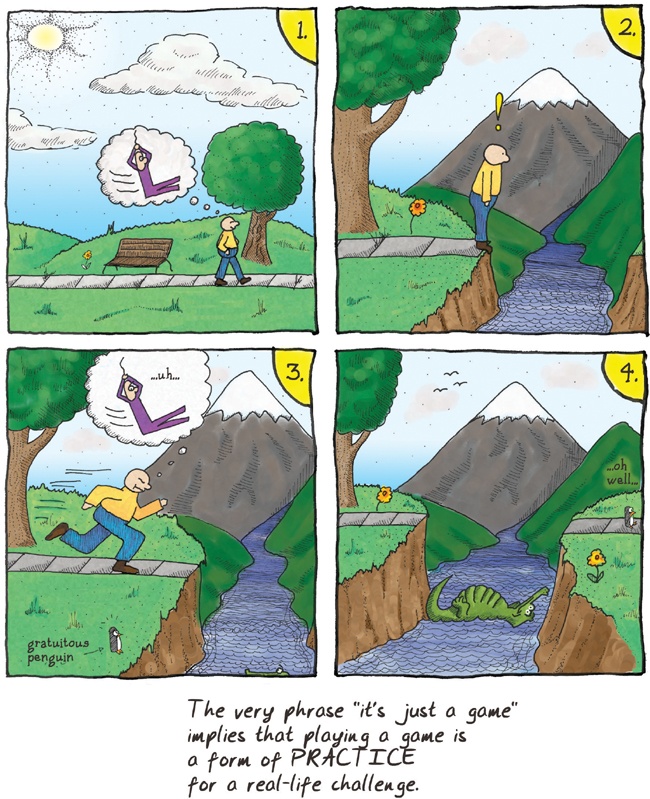

We also don’t put aside the notion of constructing abstract models of reality in order to practice with them. We practice our speeches in front of mirrors, run fire drills, go through training programs, and role-play in therapy sessions. There are games all around us. We just don’t call them that.

As we age, we think that things are more serious and that we must leave frivolous things behind. Is that a value judgment on games or is it a value judgment on the content of a given game? Do we avoid the notion of fun because we view the content of the fire drill as being of greater import?

Most importantly, would fire drills be more effective if they were fun activities? There is a design practice called “gamification” which attempts to use the trappings of games (reward structures, points, etc.) to make people engage more with product offerings. Does it miss the point of games? It is often layered on top of systems that lack the rich interpretability of a good game. A reward structure alone does not a game make.*

If games are essentially models of reality, then the things that games teach us must reflect on reality.

My first thought was that games are models of hypothetical realities, since they often bear no resemblance to any reality I know.

As I looked deeper, though, I found that even whacked-out abstract games do reflect underlying reality. The guys who told me these games were all about vertices were correct. Since formal rule sets are basically mathematical constructs, they always end up reflecting forms of mathematical truth, at the very least. (Formal rule sets are the basis for most games, but not all—there are classes of games with informal rule sets,* but you can bet that little kids will cry “no fair” when someone violates an unstated assumption in their tea party.)

Sadly, reflecting mathematical structures is also the only thing many games do.

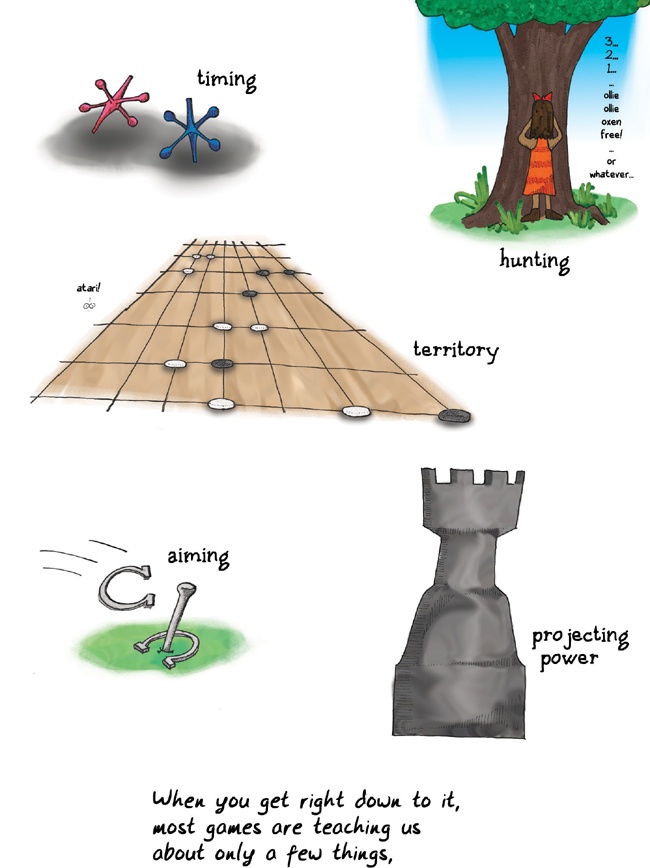

The real-life challenges that games prepare us for are almost exclusively ones based on the calculation of odds. They teach us how to predict events. A huge number of games simulate forms of combat. Even games ostensibly about building are usually framed competitively.

Given that we’re basically hierarchical and strongly tribal primates,* it’s not surprising that so many of the basic lessons taught by our early childhood play are about power and status. Think about how important these lessons still are within society, regardless of your particular culture. Games almost always teach us tools for being the top monkey or tribe of monkeys.

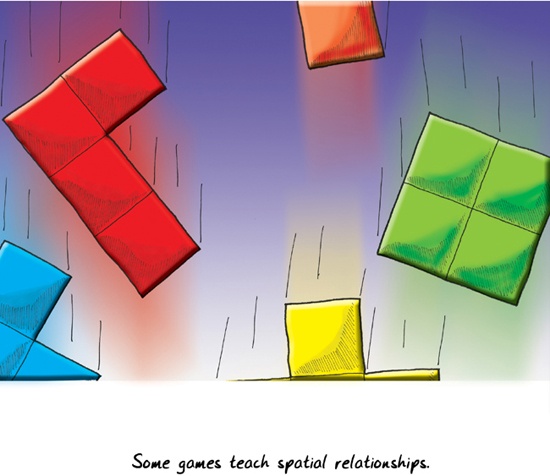

Games also teach us how to examine the environment, or space, around us.* From games where we fit together odd shapes to games where we learn to see the invisible lines of power projection across a grid, much effort is spent in teaching us about territory. That is what tic-tac-toe is essentially all about.

Spatial relationships are, of course, critically important to us. Some animals might be able to navigate the world using the Earth’s magnetic field, but not us. Instead, we use maps and we use them to map all sorts of things, not just space. Learning to interpret symbols on a map, assess distance, assess risk, and remember caches must have been a critically important survival skill when we were nomadic tribesmen. Most games incorporate some element of spatial reasoning. The space may be a Cartesian coordinate space,* like what we see on a soccer field, or it may be a directed graph* like we see in “racetrack” board games. Mathematicians might even point out that something like a tennis court could be both at the same time.* Classifying, collating, and exercising power over the contents of a space is one of the fundamental lessons of all kinds of gameplay.

Examining space also fits into our nature as toolmakers. We learn how things fit together.* We often abstract this a lot—we play games where things fit together not only physically, but conceptually as well.* We map things like temperature. We map social relationships (as graphs of edges and vertices, in fact). We map things over time. By playing games of classification and taxonomy,* we extend mental maps of relationships between objects. With these maps, we can extrapolate behaviors of these objects.

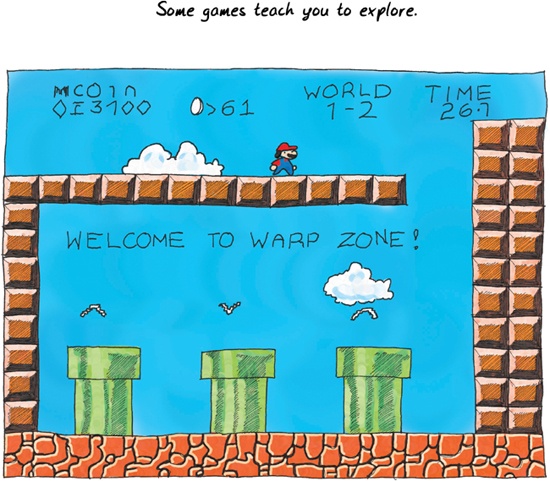

Exploring conceptual spaces is critical to our success in life. Merely understanding a space and how the rules make it work isn’t enough, though. We also need to understand how it will react to change to exercise power over it. This is why games progress over time. There are almost no games that take just one turn.*

Let’s consider “games of chance” that use a six-sided die. Here we have a possibility space—values labeled 1 through 6. If you roll dice against someone, the game you are playing might seem to end very quickly. You also might feel you don’t have much control over the outcome. You might think an activity like this shouldn’t be called a game. It certainly seems like a game you can play in one turn.

But I suggest gambling games like this are actually designed to teach us about odds. You usually don’t just play for one turn, and with each turn you try to learn more about how odds work. (Unfortunately, you often prove you didn’t learn the lesson—especially if you are gambling for money.*) We know from experiments that probability is something our brains have serious trouble grasping.

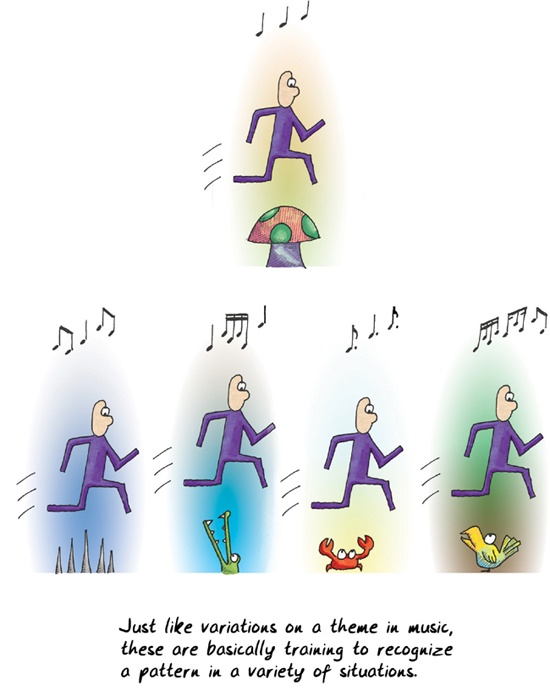

Exploring a possibility space is the only way to learn about it. Most games repeatedly throw evolving spaces at you so that you can explore the recurrence of symbols within them. A modern video game will give you tools to navigate a complicated space, and when you finish, the game will give you another space, and another, and another.

Some of the really important parts of exploration involve memory. A huge number of games involve recalling and managing very long and complex chains of information. (Think about counting cards in blackjack* or playing competitive dominoes.*) Many games involve thoroughly exploring the possibility space as part of their victory condition.

In the end, most games have something to do with power. Even the innocuous games of childhood tend to have violence lurking in their heart of hearts. Playing “house” is about jockeying for social status. It is richly multileveled, as kids position themselves in authority (or not) over other kids. They play-act at using the authority that their parents exercise over them. (There’s this idealized picture of young girls as being all sweetness and light, but there are few more viciously status-driven groups on earth.*)

Consider the games that get all the attention lately: shooters,* fighting games,* and war games. They are not subtle about their love of power. The gap between these games and cops and robbers is small as far as the players are concerned. They are all about reaction times, tactical awareness, assessing the weaknesses of an opponent, and judging when to strike. Just as my playing guitar was in fact preparing me for playing mandolin by teaching me skills beyond basic guitar fretting, these games teach many skills that are relevant in a corporate setting. It is easy to pay attention to the obvious nature of a particular game and miss the subtler point; be it cops and robbers or CounterStrike,* the real lessons are about teamwork and not about aiming. In fact, the training provided by shooting a virtual gun is worse than useless in teaching you how to shoot a real one.*

Think about it: teamwork is a far deadlier tool than sharpshooting.

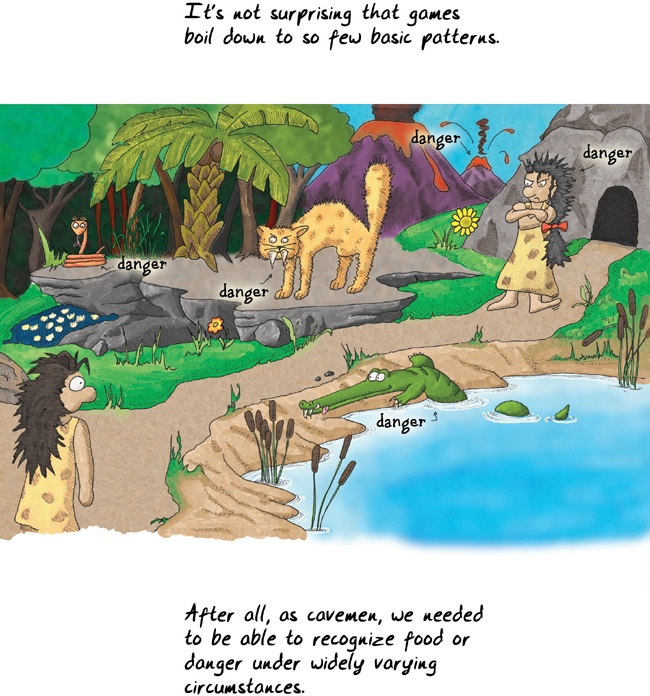

Many games, particularly those that have evolved into the classic Olympian sports, can be directly traced back to the needs of primitive humans to survive under very difficult conditions. Many things we have fun doing are in fact training us to be better cavemen. We learn skills that are antiquated. Most folks never need to shoot something with an arrow to eat, and nowadays we run marathons or other long races mostly to raise funds for charities.

Many games have become obsolete and are no longer played. During World War II, there were games about rationing supplies.*

Nonetheless, we have fun mostly to improve our life skills. And while there may be something deep in our reptile brains that wants us to continue practicing aiming or sentry-posting, we do in fact evolve games that are more suited to our modern lives.

For example, there are many games in my collection that relate to large-scale network building. Building railway lines or aqueducts wasn’t exactly a caveman activity. As humans have evolved, we’ve changed around our games. In early versions of chess, queens weren’t nearly as powerful a piece as they are today.*

Farming used to be a much bigger part of the typical person’s life than it is in industrialized societies. In the ancient mancala* family of games, players “sow seeds,” and rotate them through “houses.” In some variants, you are not supposed to leave your opponent without any seeds.

For a long time, we had few new games about farming, perhaps because there was no need to model an activity that one participated in every day. When they did return in force in the form of casual online games, they were really games about running a business, not about crop rotation and cooperation. Today’s farming games won’t actually help you feed yourself from crops.*

In general, the level of mathematical sophistication required by games has risen dramatically over the course of human history, as common people learned how to do sums. Word games were once restricted to the elite, but today they are enjoyed by the masses.

Games do adapt, but perhaps not as fast as we might wish, since almost all of these games are still, at their core, about the same activities even though they may involve different skill sets: resource allocation, force projection, territory control, and so on.

In some ways games can be compared to music (which is even more mathematically driven). Music excels at conveying a few things—emotion being paramount among them—but as a medium, is not very good at conveying things outside of its “sweet spot.” Games also seem to have a sweet spot. They do very well at active verbs: controlling, projecting, surrounding, matching, remembering, counting, and so on. Games are also very good at quantification.

By contrast, literature can tackle all of the above and more. Over time, language-based media have tackled increasingly broader subjects. Are game systems simply more limited than literature, like music is?

Pure systems probably cannot convey the same breadth of content that literature can. That said, games are capable of modeling situations of greater richness and complexity than many assume. Games like Diplomacy* are evidence that remarkably subtle interactions can be modeled within the confines of a rule set, and traditional role-playing can reach the same heights as literature in the right hands.* But it is an uphill battle for the medium nonetheless, simply because games, at their core, are about teaching us survival skills. As we all know, when you’re worried about subsistence and survival, more refined things tend to fall by the wayside.

Of course, games are a “compound” medium, and can have stories, artwork, and music all working alongside the game system. And at that point, games can have an incredible expressive breadth, with potential that has not yet been fulfilled.

It’s worth asking ourselves what skills are more commonly needed today. Games should be evolving towards teaching us those skills.

The entire spread of games for children is fairly limited, and hasn’t changed much over time. The basic skills needed by children are the same. Perhaps we need a few more games about using touchscreens, but that’s about it. Adults, on the other hand, could use new games that teach more relevant skills. Most of us no longer hunt our own food, and we no longer live in danger every moment of our lives. It’s still valuable to train ourselves in some of the caveman traits, but we need to adapt.

Some traits are relevant but need to change because conditions have changed. Interesting research has been done into what people find disgusting, for example. Disgust is a survival trait that points us away from grayish-green, mucousy, slimy things.* It does so because that was the most likely vector for illness.

Today it might be the electric blue fluid that is the real risk—don’t drink any drain cleaner—and we have no inborn revulsion towards it. In fact, it’s made electric blue to make it seem aseptic and clean. That’s a case where we should supplement our instincts with training, since I doubt there’s anything I can drink under my kitchen sink.

Some of the new patterns we need to learn in our brave new world run contrary to our instinctive behaviors. For example, humans are tribal creatures. We not only fall readily into groups run by outsize personalities,* but we’ll often subsume our better judgment in doing so. We also seem to have an inbred dislike of groups not our own.* It is very easy to get humans to regard a different tribe as less than human, particularly if they look or act differently in some way.

Maybe this was a survival trait at one time, but it’s not now. Our world grows ever more interdependent; if a currency collapse occurs on the other side of the world, the price of milk at our local grocery could be affected. A lack of empathy and understanding of different tribes and xenophobic hatred can really work against us.

Most games encourage “othering” the opponent, treating him as “not like us,” teaching a sort of ruthlessness that is a proven survival trait. But historically, we’re not likely to need or want the scorched-earth victory, despite legends of “sowing salt” over conquered cities.* Can we create games that instead offer us greater insight into how the modern world works?

If I were to identify other basic human traits that game designs currently tend to reinforce, and that may be obsolete legacies of our heritage, I might call out traits like:

Blind obedience to leaders and cultism: We’re willing to do things in games simply because “those are the rules.”*

Rigid hierarchies or binary thinking: Games, because they are simplified, quantized models, usually reinforce notions about class, jobs, identity, and other fluid concepts.

The use of force to resolve problems: We don’t tend to see a way to form a treaty with our opponent in chess.

Like seeking like, and its converse, xenophobia: Seen in countless role-playing games where we slaughter endless orcs.

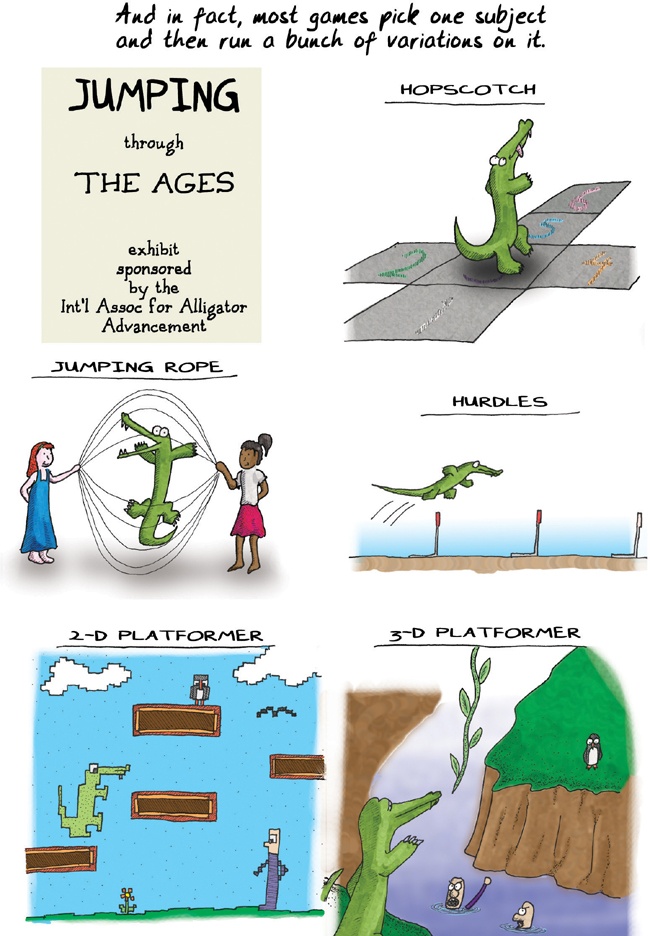

For better or worse, games have been ringing changes on the same few subjects. There’s probably something deep in the reptile brain that is deeply satisfied by jumping puzzles,* but you’d think that by now we would have jumped over everything in every possible way.

When I first started playing games, everything was tile-based,* meaning that you moved in discrete squares, as if you were popping from tile to tile on a tiled floor. Nowadays you move in a much freer way, but what has changed is the fidelity of the simulation, not what we’re simulating. The skills required are perhaps closer to being what they are in reality, and yet an improvement in the simulation of crossing a pond full of alligators is not necessarily a real improvement in what the game teaches us.

The mathematical field of studying shape, and the way in which apparent shapes can change but remain fundamentally the same, is called topology.* It can be helpful to think of games in terms of their topology.

Early platform videogames* followed a few basic gameplay paradigms:

“Get to the other side” games: Frogger,* Donkey Kong,* Kangaroo.* These are not really very dissimilar. Some of these featured a time limit, some didn’t.

“Visit every location” games: Probably the best-known early platformer like this was Miner 2049er.* Pac-Man and Q*Bert* also made use of this mechanic. The most cerebral of these were probably Lode Runner and Apple Panic,* where the map traversal could get very complex, given the fact that you could modify the map to a degree.

Games started to meld these two styles, then they added scrolling environments. Eventually designers added playing in 3-D on rails,* and finally made the leap to true 3-D* with Mario 64.

A modern platformer makes use of all of these dimensions:

“Get to the other side” is still the basic paradigm.

“Visit all the map” is handled by a “secrets”* system.

Time limits add another dimension of challenge.

Since the original Donkey Kong, players have been able to pick up a hammer* to use as a weapon. One of the most common signs of incremental innovation in game design is designers simply adding more of a given element, rather than adding a new element. Hence, today we have a bewildering array of weapons.

Platformers have now covered all the dimensions. They have started pulling in elements of racing and flying games as well as fighters and shooters. They have built in secret discovery, time limits, and power-ups. Recent games have included more robust stories, and even elements from role-playing games. Are there more dimensions on which to expand?

Going from Pong to a modern tennis game is not so large a leap. How odd that we’ve ended up in the recursive pattern of making games that model other games—it suggests that there’s something that the real-life sport of tennis can teach that doesn’t require running around on a court in a white outfit. Nonetheless, rather than teaching the skill of hurling rocks and judging trajectories, it would be nice if more games instead taught things like whether or not the price of oil is going to rise in response to signing or not signing a global warming treaty.*

This may sound bleak, but in fact, it’s not. The skills needed around a meeting room table and the skills needed at the tribal council are not so different, after all. There are whole genres of games that are about husbandry, resource management, logistics, and negotiation. If anything, the question to ask might be why the most popular games are the ones that teach obsolete skills, while the more sophisticated ones that teach subtler skills tend to reach smaller markets.

A lot of it can probably be traced to visceral appeal. Remember, we live most of our lives in the unconscious. Action games let us stay there, whereas games that demand careful consideration of logistics might require logical, conscious thought. So we play variations on old, often irrelevant challenges because, frankly, it’s easier.

We’ve evolved exquisite sensitivity to visceral challenges. A survey of games featuring jumping found that the games with the “best controls” all shared an important characteristic: when you hit the jump button, the character on screen spent almost exactly the same amount of time in the air.* Games with “bad controls” violated this unspoken assumption. I’m pretty sure that if we went looking, we’d find that good jumping games have been unscientifically adhering to this unspoken rule for a couple of decades, without ever noticing its existence.

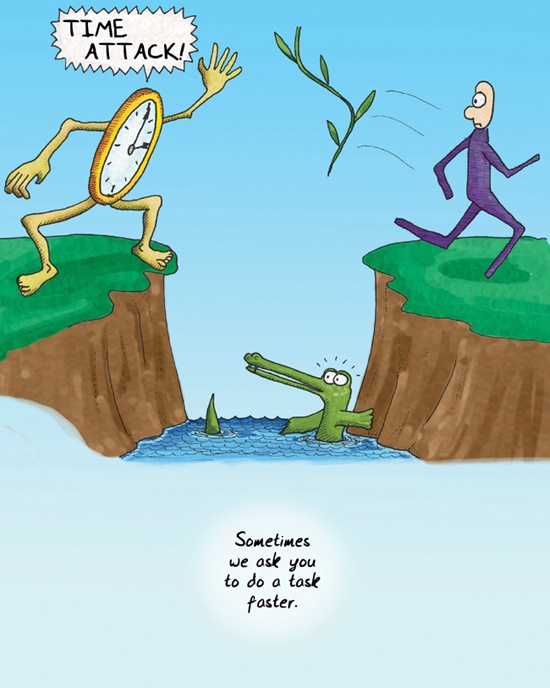

That’s hardly the only case of our adjusting our work to better target the unconscious mind. A very common feature of action games, for example, is to push you through a task faster and faster. This is purely intended to address the visceral reaction and the autonomic nervous system. When you learn any physical skill, you are told to do it slowly at first, and slowly increase the speed as you master the task. The reason is that developing speed without precision is not all that useful. Going slowly lets you practice the precision first, make it unconscious, and then work on the speed.

You don’t tend to see “time attack”* modes in strategy games for this same reason. The tasks in the strategic games are not about automatic responses, and therefore the training to execute at reflex levels of speed would be misguided. (If anything, a good strategy game will teach you not to get too familiar with the situation and will keep you on your toes.)

This whole approach is intended for learning by rote. When I was a kid, I had a game for the Atari 2600* console called Laser Blast.* I got to the point where I could get a million points at the maximum difficulty setting without ever dying. With my eyes closed. This is the same sort of training that we put our militaries through—the training of rote and reflex. It’s not a very adaptable mode of training, but it is desirable in many cases.

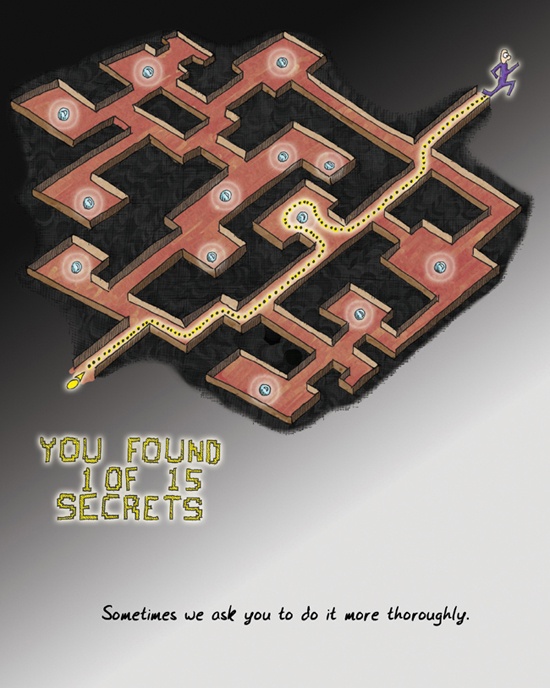

A more interesting tactic that applies to a wider range of games is asking the player to be thorough. This is a broader survival skill. It requires patience, and a certain enjoyment in discovery. It also works against our inclination to work directly on the final goal.

In many games, you are asked to find “secrets”, or to explore an area completely. This teaches many interesting things, such as considering a problem from all angles, making sure that you have all the necessary information before you make a decision, and that thoroughness is often better than speed. Not to denigrate training by rote and reflex, but this is a much subtler and interesting set of skills to teach, and one that is more widely applicable to the modern world.

Games have these characteristics:

They present us with models of real things—often highly abstracted.

They are generally quantified or even quantized* models.

They primarily teach us things that we can absorb into the unconscious, as opposed to things designed to be tackled by the conscious, logical mind.

They mostly teach us things that are fairly primitive behaviors (but they don’t have to).

Seen in this light, the evolution of the modern video game can largely be explained in terms of topology. Each generation of game can be described by a relatively minute alteration in the shape of the play space. For example, there have only really been around five fighting games* in all of videogaming history. Significant advances have been limited to a few features like movement on a plane, movement in 3-D, and the addition of “combos”* or sequences of moves. The games look different because of their content, not their underlying lessons.

This is not to say that many of the classic fighting games didn’t bring significant incremental advances. Of course they did. But did they effectively “add another hole to the donut”?

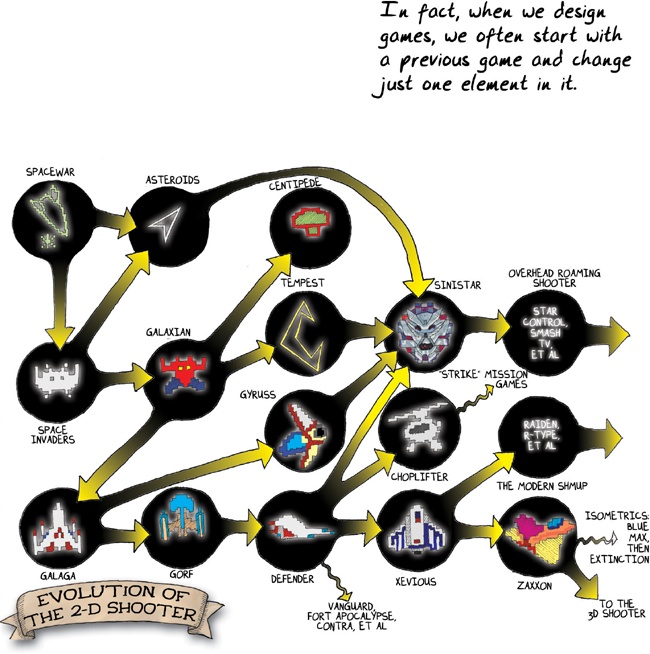

Consider the evolution of the 2-D shooter or “shmup.”* Space Invaders* offered a single screen with enemies that marched predictably. After that came Galaxian,* which had no defenses and enemies that attacked a bit more aggressively.

Simple topological variants then ensued: Gyruss* and Tempest* are just Galaxian in a circle. Gorf* and others added scrolling, and also had an end boss and stages that changed in nature as you progressed. Zaxxon* added verticality, which was then quickly thrown away in the development of the genre. Centipede* gave you some room to maneuver at the bottom, and a charming setting, but isn’t really that different from Galaxian and Space Invaders. Asteroids* is an inverted circle: you’re in the middle, and the enemies come from outside.

Galaga was probably the most influential of all of these, because it added bonus levels and the power-up, a concept that has become standard in every shmup since. Xevious and Vanguard added alternate modes of fire (bombs and firing in other directions). Robotron* and Defender* are special cases. Both have the element of rescuing. This has been pretty much abandoned today (sadly—though Choplifter* was a wonderful sidetrack there).

Now, I don’t know what the first 2-D shooter to have power-ups and scrolling and bosses* at the end of stages was, but a case can be made that there hasn’t been a 2-D shooter with a different “shape” since then. Unsurprisingly, the shooter genre has stagnated and lost market share. After all, we learned that mechanic a long time ago, and everything since has been learning patterns that we know to be artificial and unlikely to be repeated anywhere.

This offers a possible algorithm for innovation: find a new dimension to add to the gameplay. We saw this in the way that puzzle games evolved after Tetris:* people started trying to do it with hexagons,* with three dimensions, and eventually, pattern matching of colors became the thing that replaced spatial analysis. If we really want to innovate on puzzle games, how about exploring puzzle games based on time* rather than space, for example?

Get Theory of Fun for Game Design, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.