As explained earlier, Samba can help Windows and Unix computers coexist in the same network. However, there are some specific reasons why you might want to set up a Samba server on your network:

You don’t want to pay for—or can’t afford—a full-fledged Windows server, yet you still need the functionality that one provides.

The Client Access Licenses (CALs) that Microsoft requires for each Windows client to access a Windows server are unaffordable.

You want to provide a common area for data or user directories to transition from a Windows server to a Unix one, or vice versa.

You want to share printers among Windows and Unix workstations.

You are supporting a group of computer users who have a mixture of Windows and Unix computers.

You want to integrate Unix and Windows authentication, maintaining a single database of user accounts that works with both systems.

You want to network Unix, Windows, Macintosh (OS X), and other systems using a single protocol.

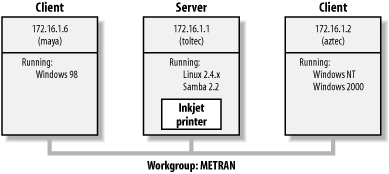

Let’s take a quick tour of

Samba in action. Assume that we have

the following basic network configuration: a Samba-enabled Unix

system, to which we will assign the name toltec,

and a pair of Windows clients, to which we will assign the names

maya and aztec, all connected

via a local area network (LAN). Let’s also assume

that toltec also has a local inkjet printer

connected to it, lp, and a disk share named

spirit—both of which it can offer to the

other two computers. A graphic of this network is shown in Figure 1-1.

In this network, each computer listed shares the same workgroup. A workgroup is a group name tag that identifies an arbitrary collection of computers and their resources on an SMB network. Several workgroups can be on the network at any time, but for our basic network example, we’ll have only one: the METRAN workgroup.

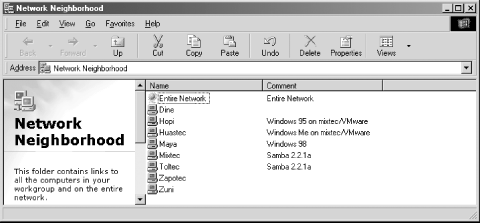

If everything is properly

configured, we should be able to see the Samba server,

toltec, through the Network Neighborhood of the

maya Windows desktop. In fact, Figure 1-2 shows the Network Neighborhood of the

maya computer, including toltec

and each computer that resides in the METRAN workgroup. Note the

Entire Network icon at the top of the list. As we just mentioned,

more than one workgroup can be on an SMB network at any given time.

If a user clicks the Entire Network icon, she will see a list of all

the workgroups that currently exist on the network.

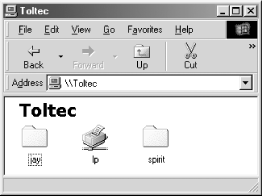

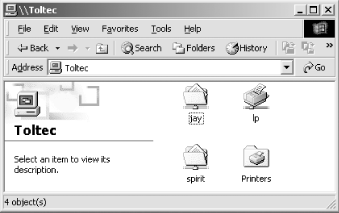

We can take a closer look at the toltec server by

double-clicking its icon. This contacts toltec

itself and requests a list of its

shares—the file and printer

resources—that the computer provides. In this case, a printer

named lp, a home directory named

jay, and a disk share named

spirit are on the server, as shown in Figure 1-3. Note that the Windows display shows hostnames

in mixed case (Toltec). Case is irrelevant in hostnames, so you might

see toltec, Toltec, and TOLTEC in various displays or command output,

but they all refer to a single system. Thanks to Samba, Windows 98

sees the Unix server as a valid SMB server and can access the

spirit folder as if it were just another system

folder.

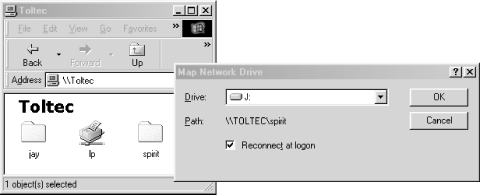

One popular Windows feature is the ability to map a drive letter (such as E:, F:, or Z:) to a shared directory on the network using the Map Network Drive option in Windows Explorer.[1] Once you do so, your applications can access the folder across the network using the drive letter. You can store data on it, install and run programs from it, and even password-protect it against unwanted visitors. See Figure 1-4 for an example of mapping a drive letter to a network directory.

Take a look at the Path: entry in the dialog box of Figure 1-4. An equivalent way to represent a directory on a network computer is by using two backslashes, followed by the name of the networked computer, another backslash, and the networked directory of the computer, as shown here:

\\network-computer\directory

This is known as the

Universal

Naming Convention (UNC) in the Windows world. For example, the dialog

box in Figure 1-4 represents the network directory

on the toltec server as:

\\toltec\spirit

If this looks somewhat familiar to you, you’re

probably thinking of uniform resource

locators

(URLs), which are addresses that web

browsers such as Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer use to

resolve systems across the Internet. Be sure not to confuse the two:

URLs such as http://www.oreilly.com use forward slashes

instead of backslashes, and they precede the initial slashes with the

data transfer protocol (i.e., ftp, http) and a colon (:). In reality,

URLs and UNCs are two completely separate things, although sometimes

you can specify an SMB share using a URL rather than a UNC. As a URL,

the \\toltec\spirit share would be specified as

smb://toltec/spirit.

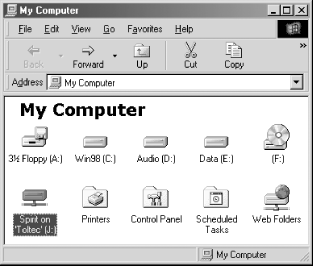

Once the network drive is set up, Windows and its programs behave as if the networked directory were a local disk. If you have any applications that support multiuser functionality on a network, you can install those programs on the network drive.[2] Figure 1-5 shows the resulting network drive as it would appear with other storage devices in the Windows 98 client. Note the pipeline attachment in the icon for the J: drive; this indicates that it is a network drive rather than a fixed drive.

My Network Places, found in Windows Me, 2000, and XP, works

differently from Network Neighborhood. It is necessary to click a few

more icons, but eventually we can get to the view of the

toltec server as shown in Figure 1-6. This is from a Windows 2000 system. Setting

up the network drive using the Map Network Drive option in Windows

2000 works similarly to other Windows versions.

You probably noticed that the printer

lp appeared under the available shares for

toltec in Figure 1-3. This

indicates that the Unix server has a printer that can be shared by

the various SMB clients in the workgroup. Data sent to the printer

from any of the clients will be spooled on the Unix server and

printed in the order in which it is received.

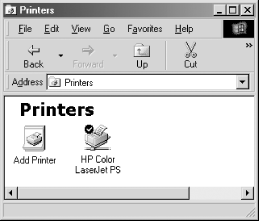

Setting up a Samba-enabled printer on the Windows side is even easier than setting up a disk share. By double-clicking the printer and identifying the manufacturer and model, you can install a driver for this printer on the Windows client. Windows can then properly format any information sent to the network printer and access it as if it were a local printer. On Windows 98, double-clicking the Printers icon in the Control Panel opens the Printers window shown in Figure 1-7. Again, note the pipeline attachment below the printer, which identifies it as being on a network.

As mentioned earlier, Samba appears in Unix as a set of daemon programs. You can view them with the Unix ps command; you can read any messages they generate through custom debug files or the Unix syslog (depending on how Samba is set up); and you can configure them from a single Samba configuration file: smb.conf. In addition, if you want to get an idea of what the daemons are doing, Samba has a program called smbstatus that will lay it all on the line. Here is how it works:

# smbstatus

Processing section "[homes]"

Processing section "[printers]"

Processing section "[spirit]"

Samba version 2.2.6

Service uid gid pid machine

-----------------------------------------

spirit jay jay 7735 maya (172.16.1.6) Sun Aug 12 12:17:14 2002

spirit jay jay 7779 aztec (172.16.1.2) Sun Aug 12 12:49:11 2002

jay jay jay 7735 maya (172.16.1.6) Sun Aug 12 12:56:19 2002

Locked files:

Pid DenyMode R/W Oplock Name

--------------------------------------------------

7735 DENY_WRITE RDONLY NONE /u/RegClean.exe Sun Aug 12 13:01:22 2002

Share mode memory usage (bytes):

1048368(99%) free + 136(0%) used + 72(0%) overhead = 1048576(100%) totalThe Samba status from this output provides three sets of data, each

divided into separate sections. The first section tells which systems

have connected to the Samba server, identifying each client by its

machine name (maya and aztec)

and IP (Internet Protocol) address. The second section reports the

name and status of the files that are currently in use on a share on

the server, including the read/write status and any locks on the

files. Finally, Samba reports the amount of memory it has currently

allocated to the shares that it administers, including the amount

actively used by the shares plus additional overhead. (Note that this

is not the same as the total amount of memory that the

smbd or nmbd processes are

using.)

Don’t worry if you don’t understand these statistics; they will become easier to understand as you move through the book.

[1] You can also right-click the shared resource in the Network Neighborhood and then select the Map Network Drive menu item.

[2] Be warned that many end-user license agreements forbid installing a program on a network so that multiple clients can access it. Check the legal agreements that accompany the product to be absolutely sure.

Get Using Samba, Second Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.