Chapter 1. What Is the Token Economy?

Token economics can be understood as a subset of economics that studies the economic institutions, policies, and ethics of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services that have been tokenized. This report outlines the current state of tokenization of our economy and discusses potential effects and dynamics of a future “token economy.”

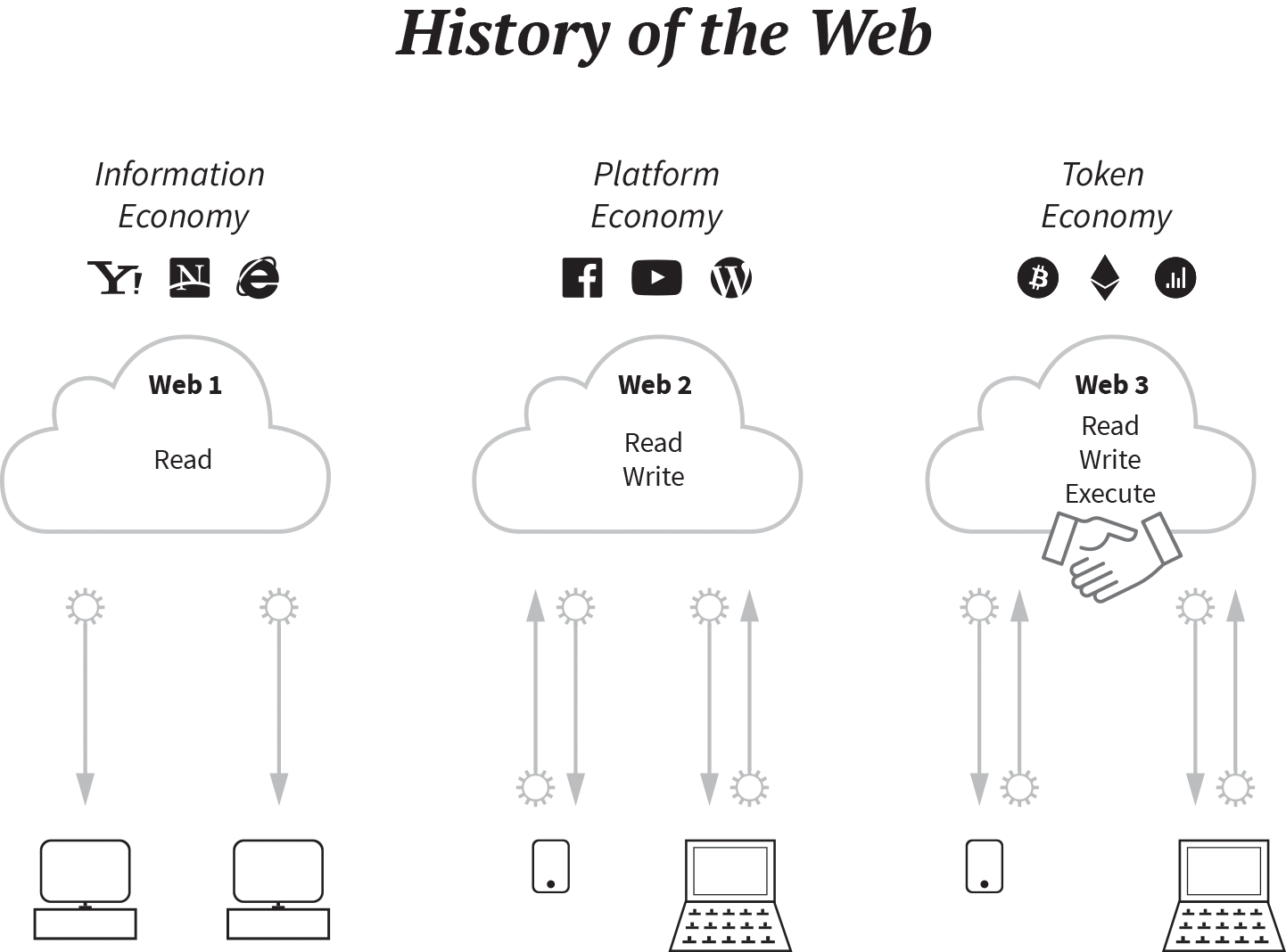

Blockchain technology seems to be the driving force of the next-generation internet, what many refer to as Web3.1 Web3 enables tokenized economic interactions without intermediaries (see Figure 1-1). It provides a unique set of data, a universal state layer, also referred to as the ledger, which is collectively managed by a network of untrusted computers. This unique state layer allows us to send digital values in the form of tokens entirely peer to peer (P2P), circumventing the double-spending problem.2 Sending digital values over the web has therefore become as cheap and easy as sending an email. As of April 2019 more than 2,200 publicly traded tokens are listed on CoinMarketCap, and more than 175,000 Ethereum token contracts were found on the Ethereum main network. In June 2019, social media giant Facebook announced that it is working on its own token (the Libra token) and Web3 infrastructure (the Libra network).